Annie Leibovitz Shares Her Vision in Monaco

The newest gallery openings this week, including the dark side of the American dream, traditions of Aboriginal Australian painting, a cheeky photographer, and more.

On this special episode sponsored by Lumens, Dan meets three extraordinary studios in the field of design: British upstart Tom Massey uses radical materials and a sustainable approach to his gardens; Brooklyn and Athens–based duo Eleni Petaloti and Leonidas Trampoukis of Objects of Common Interest create spaces and objects that defy convention (but don’t call them “Instagrammable”); and Venice-based Lucia Massari produces wild, ultra-contemporary examples of Murano glass.

TRANSCRIPT

Lucia Massari: And when the master works on your piece, he always puts a little bit of himself into your piece, which can be really annoying. But I think once you let go on these things, then everything, also like errors, are part of the final piece as well. So I think it’s all about being open to all these things that are coming that you will never actually predict.

Dan Rubinstein: Hi, I’m Dan Rubinstein and this is The Grand Tourist. I’ve been a design journalist for nearly 20 years, and this is my personalized guided tour for the worlds of fashion, art, architecture, food, and travel, all the elements of a well lived life. And welcome to a very special episode brought to you by Lumens, The Grand Tourist Introduces.

Today I’ll speak with four rising stars in the world of design, each with their own unique story to tell. We’ll meet a husband and wife duo based both in Brooklyn and Athens behind an experimental firm doing mind-bending work, both with artistic installations and experimental furniture. And we’ll meet a young talent in Venice, Italy, who is challenging the status quo and producing whimsical and progressive works in a traditionally male dominated field to the delight of collectors.

But first, we’ll meet an award-winning landscape and garden designer from London, who is challenging his own field status quo with an eye towards sustainability and materiality in completely chic ways, Tom Massey. His first book, RHS Resilient Garden, published with the Royal Horticultural Society, takes the rather traditional side of English gardening and applies a series of practices to address everything from soil health to mitigating the effects of climate change. Tom takes an unexpected approach to his designs. He inserted an insect laboratory to his design for this year’s Chelsea Flower Show where he won the silver medal and he took home the gold in 2021 where he created a naturalistic garden, the first said such to be approved by the Country’s soil association. I caught at with Tom from his studio to chat about how his unlikely transition from a career in animation to gardens became a reality, how he uses unconventional materials such as barbed wire and just what is a resilient garden anyhow?

Your work is really incredible and I’ve been trying to absorb as much as I can. Tell me a little bit about your early life and how you got started. I heard you were raised in London, but you kind of spent your summers in rural Cornwall. Tell me a little bit about that.

Tom Massey: Yeah, so I grew up in Richmond in southwest London, which is a kind of leafy green suburb of London. So you can get into central London in about 25 minutes on the train, but you’ve got Richmond Park, which is 10 miles around the perimeter if you were walking. So really quite a wild feeling park in an urban environment. I think it’s one of the biggest national parks in Europe and it’s full of wild deer, all sorts of interesting wildlife. So you can see things like green woodpeckers that feed on yellow [inaudible 00:03:11], and the relationship between them is of special scientific interest.

So the Richmond Park was definitely, in my formative years, a real inspiration on me, I think, a landscape that I really responded well to and was inspired by. So growing up in Richmond, I had that access to green space, got the River Thames as well, and the towpath to the river. It’s known as one of the best walks in and around London, between Richmond to Kingston and further out. It’s really green and leafy and lots of amazing landscape around where I grew up.

And then it in summer holidays, my parents always took us down to Cornwall, and that was an area called the Roseland Peninsula. And really we were kind of allowed to run wild. So we stayed in this very dilapidated old house that was owned by a family friend and we just were kind of set loose really. We could go and explore the cliffs, climb down to the beach, swim in the sea, explore the garden of that house. Also had a really romantic wild field to it. It had been kind of unmaintained for some years, so you could crawl through hedges or explore the old orchard. So I think growing up as a young boy, I just had lots of access to nature and to green space, and I think that really stuck with me as I grew older.

So why study garden design? What were your sort of aspirations? How did you find yourself doing that?

So when I was 16, I dropped out of college. I wasn’t really enjoying the A-levels that I was doing. I think I chose two academic subjects, doing things like IT and PE quite kind of intensive, mainly written or desk-based work. And I decided to go and work for six months with a landscape gardener as he called himself. But he was kind of a garden designer, but he also did the implementation. So I spent six months working with him, really enjoyed it. But alongside that, I also had ambitions to do an art foundation, which I don’t know if you have a similar thing in the states, but it’s a year long course where you try out all sorts of different artistic subjects. So you try a bit of film, a bit of animation, a bit of photography, some live drawing. You do a range of things to help you decide what it is you want to do.

And doing that course, I really resonated with animation as a medium. So I did a BA honour’s degree in animation production at the Arts University in Bournemouth. So that was a three-year course. And then when I graduated from that, I worked for a bit in that field. So doing things for brands, making small animations and bringing other people’s ideas to life. I think what I found with that was just way too much time sitting in a dark room with nothing. Although you’re creating content and creative content, nothing physical. I think that’s what I felt I was missing in my career was that the creativity I felt I did have, but the physical making of things I felt was missing.

So whilst doing that, I also took a lease on a warehouse space in East London, an area called Haggerston. And me and a couple of friends, we renovated it and turned it into a coworking space for people working in creative industries alongside a small cafe. Part of that was I had a small outside space, and that kind of reminded me of the joy of designing and then bringing to fruition, taking something from paper into physical space.

So my wife and I, my girlfriend at the time, we sold our shares in that project to our friends and used it to fund a kind of retraining, a career shift. So I enrolled at the London College of Garden Design, which is based at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Q and did the garden design diploma course, which was a year long course. And yeah, I haven’t really looked back since. I’d just absolutely loved it, really enjoyed the process of, well, the design process, but also working with plants, working with materials, spending time outside, observing other people’s work, going to visit. So I really just kind of absorbed as much as I could in that year. And then on graduation, I worked for a couple of years part-time with Andrew Wilson and Gavin McWilliams. So Andrew is the course director, and they were based in Chiswick. I was based in Richmond, so fairly nearby. So I spent two days a week working with them and the rest of the week I was building my own practice.

So how was your studio set up today?

So today in the studio it’s me as director, principal designer, and then I’ve got four people that work with me as project designers. So always at the start of any new project, I kind of assign a project designer to it and then we work together on the project. Sometimes it’s more than one designer depending on the size of the project. So I oversee every single project that comes through the studio, do most of the client liaison and communications with the client.

And you’re known for this organic approach to your work, and you recently had some work that dealt with this idea of the forest garden. And I’m wondering if you could explain to the listener what a forest garden is and what your take on it is.

Yeah. So a forest garden is, or a food forest some people refer to it as, is essentially a garden that mimics the layers of a natural forest. So you’ve got the tree canopy layer, you’ve got climbing plants that climb up the trees or climb up fences if it’s in a residential garden, shrub layer. And then you’ve got the kind of understory ground cover and then the roots and the things that happen below or in the soil. So really you’re trying to create this self-supporting ecosystem of plants that functions like it would in a natural setting. But typically every plant is chosen for a purpose. So it might be that the plant is medicinal or edible or has some kind of productive use even for making twine or for making bamboo, for example, using as canes. So the idea is that every plant is chosen for a reason and has a purpose within the garden and also is supporting and in balance with the other species that have been chosen.

And in terms of that kind of utility, are there some species that you think you could name that maybe have utility beyond what it might be completely obvious?

Yeah. So things like comfrey or symphytum officinale is a really good plant because of the nutrients that it contains or plants that are nitrogen fixing, things like clover or legumes that have nitrogen storing capacity in their roots. They can provide nutrients to other plants surrounding, or you can make fertilizers from them. So they assist other plants in the landscape. But it could be as simple as a tree providing a shaded canopy for shade loving plants beneath. It’s an interesting concept and it’s quite an old… I think increasingly, I’m finding in my work going back to older learnings or older teaching organic principles is often the answer is not as complex as maybe it seems to be and we just need to stop using chemicals, stop using pesticides. Sometimes solutions to problems that we’re facing are relatively simple. It just requires a rethinking or a reframing of an approach.

And you’re known for use of unusual materials. You talked about barbed wire in the last one. In this one you have this sort of bug-eyed dome. You had a perennial sanctuary garden where there was a large sort of a court and steel bowl and as like a pond. And I’m wondering, is there a part of you obviously that maybe feels a little bit more, you know, you like to integrate objects and design a little bit more in the built environment into your work maybe that some of your peers? Or do you think is that fair to say?

Yeah, I think I’m also interested in architecture and objects. I think that is definitely fair to say. I think, as I said earlier, I was always interested in art and design and come from a kind of art and design background. So when I was younger, I was always making things, whether that’s a tree house or a little model of a… I was just always creating things, sticking things together, playing around with building things. So I think, again, that comes from quite a young age, that interest and that fascination with objects or with structures.

And when it comes to organic gardening, I hear that you’ve tried to implement these kinds of idea into show gardens and things like that. What does that actually mean? Because obviously to someone who’s interviewed many garden designers before, I’ve heard different things from different people, and obviously it sounds like a garden should be all organic as long as you’re not using maybe pesticides. What makes an organic garden per se, from your very ground floor way of seeing it?

Yeah, so I think as you say, if you’re gardening sustainably or in a way that is more aware of the environment around you, you probably are organic gardening anyway. There’s a set of principles that really apply. So it’s not using any chemical pesticides or fertilizers. So essentially, taking chemicals off the table. And that means by the very nature of doing that, you need to have a more relaxed and laid back approach, I suppose. So if you have an outbreak of a certain pest, it might be that you can put a bird feeder next to that, encourage birds in who will then eat that pest, or having a small wildlife pond that would encourage frogs or toads that might eat slugs or snails. So it’s kind of removing the nuclear options from your arsenal in a way. So not just deciding as soon as you spot anything that might be eating your plants, just to spray that with chemicals that will indiscriminately potentially poison other species that you might be less worried about.

So that’s one key principle, is trying to reduce plastic or reuse, repurpose, recycle where you can, creating compost from garden cuttings or garden waste and then incorporating that back into the soil. So here in the UK there’s an organization called the Soil Association. They certify gardens or farms or growers as organic. So there’s probably similar bodies in the US, I would imagine, who also provide that certification. For the average gardener, you are not going to go to the lengths of organic certification because it’s a lot of paperwork and a lot of time, but you can still follow the principles that people like the Soil Association promote.

Do you think people are more open to experimentation? Do you think that kind of the old guard of the Chelsea Flower Show and that kind of maybe… What’s the type of hat that you wear, that-

The straw hat.

… that you normally wear? Yeah, like a straw hat, fancy hat, kind of society sort of vibe. Do you know if people are a little bit more experimental and artistic about their approach and what they expect out of it and what they’re willing to tolerate?

I do. Yeah. I think there’s a few practitioners who are trying different things, like you mentioned earlier, using more or potentially radical materials using more or potentially radical materials, things like rubble or crushed concrete or construction waste, utilizing these things as finished landscape elements. And I think that we’ve got so much waste in the world that we could almost stop making anything and just reuse our waste for probably hundreds of years. But we’ve just got this obsession with constantly using resource, making new things, buying new things.

It’s crazy, when you think about packaging, single-use plastic packaging, even something like a spray bottle or a jam jar could be used hundreds, if not thousands of times, but we use it once and then chuck it in the recycling or just throw it away. And then it’s recycled and made into the same thing or a similar thing again and again. So we’re living at the bubble, the boom is going to happen at some point and I think we need to start to anticipate that.

And yeah, so I think a lot of people are aware of that, and particularly a lot of younger people who know that they’re going to be the ones that are living through this time. I think, as you say, the straw hat brigade, maybe … Even then, I think a lot of people at Chelsea Flower Show is typically an older, more conservative audience. I think they are shifting their perception of what they see as acceptable in garden terms.

And speaking of the forest garden concept, I do want to bring up your book Resilient Garden, which runs alongside this concept. What made you choose this topic for a book specifically and for your first book? And can you tell us a little bit about what people can expect to see inside the book?

Yeah, so the book is, it’s in partnership with the RHS, and I was really pleased to be asked. So DK are the publisher and they work a lot with the RHS, and they brought us together and said, “We’d love to write this book with Tom. We think the RHS would be great to be involved with it.” So I was given access to the RHS science team. And the RHS, not many people know, have a whole science department where they’re studying things like the pollution-capturing abilities of certain plants or how drought-tolerant plants or how good they are for pollinators or what kind of fruit and vegetables perform best. So they’ve had this incredible access to their science team to be able to ask questions and discover, read their papers and explore their research.

The book is really grounded in science and is … I suppose it starts out as an exploration, kind of what we’ve talked through, how I came to garden design and what I’m inspired by. Then it goes on to talk in more practical terms about how people can design their gardens or implement changes in the way that they garden, to become more resilient and more adaptable to climate change. And a lot of that is adapting to more extreme weather events, so planning for heat waves or droughts or for water logging in the winter.

And the middle of the book has this theoretical resilient garden, where it shows a very typical suburban plot, which probably is also very relevant to a lot of gardens in the States or in Australia or in other parts of the world. The before-garden has a very hard paved, almost zero biodiversity, just parking lot basically for cars. And then it shows how you could change that and implement some plants and change the material to a recycled gravel that’s permeable. How you can harvest rain water and store that. And how you can design a scheme that is both beneficial for humans, plants cool the air, they provide shade, they can provide food, and also for wildlife. So whilst doing that it can also provide food for pollinators or for larger mammals or birds.

So it starts off by explaining what climate change is in quite simple terms because it’s such a big subject, the book isn’t really about that. And then goes on to how to analyze your own garden and how to look at the conditions it’s facing now, but also might face in the future. And then how to implement that and design and maintain a space that is more adapted to this changing climate that we’re facing.

And so I’m curious, what is your own garden like? Or do you have your own garden?

I have a tiny courtyard, and it’s taken me about three years to get it somewhere near finished-

Oh, gosh.

… just because I’ve been doing it and around other projects, renovating my house. So the garden was definitely the last thing to be done. I guess there’s a term, busman’s holiday in the UK, where when you’ve got any downtime, you don’t necessarily want to be doing the thing that you do day in, day out.

But obviously I did want to do it, it was just finding the time. So it’s a mix of old plants from show gardens, paving that I’ve rescued from other projects, recycled gravel, a water butt that I made from an old copper tank. It’s a bit of a mishmash of other things that I’ve cobbled together, but it’s a nice space and it’s starting to come to life now.

(SPONSOR BREAK)

My next pair of guests create some of the most daring furniture and installations in collectible design. From their offices in Brooklyn and Athens, the team of Objects of Common Interest create colorful works that look like they jumped right out of an AI-generated alien landscape, in materials like resin and silicone, and installations for galleries like Nilufar in Milan, or even outdoor fountains made from biodegradable plastic. I caught up with founders Eleni Petaloti and Leonidas Trampoukis from their New York office to discover a bit about their creative process, why they love to start from scratch, and why they hate their work being called Instagrammable.

When did the two of you guys lay eyes on each other, as we say?

Eleni Petaloti: We know each other since the ’90s, believe it or not, because we are from the same city, we’re same hometown, so we knew each other even prior to architecture school, from high school. And then, it’s fun but our academic path, it’s same exactly, but he’s one year ahead. So we both went the same architecture school, polytechnic school in Greece. We both went to the same school in Paris called de La Vilette, and we both had Master’s at Columbia University, but without copying each other, it just happened to be the same steps.

And, Leo, at what point did you guys sort of connect later on in life?

Leonidas Trampoukis: Actually, the last part when we came to New York, was it was my decision to come to New York. I had to come for a Master’s and I had just met Eleni, officially met … We were together one year before that and I told her, “Listen, I’m going to New York. Come over as well.” So she came supposedly for a summer. She did a summer internship, and then one thing brought the other, we stayed for 15 years.

Wow. And when did you guys decide to start working together? How did that connection start?

EP: We actually did not decide, it just happened. If it was a decision, we wouldn’t decide to work together. It wasn’t like an official decision, “Let’s do that together.” It happened very organically. We both had different jobs. Leo was a heavy duty in architecture. Even an architect, I was working contemporary artwork for almost nine years in New York, and we received some architecture commissions and we start working late nights, weekends, like everybody does. So we start working together because it was impossible to pull a team together while you’re working for some other people. And then one brought the other, another project, another project. And officially, when I stopped working 2016 in the contemporary artwork, we also established Objects of Common Interest as a studio together.

And did LOT come first or and Objects of Common Interest was like a line from LOT, is that how I understand it?

LT: We started LOT first, because at that time we had no involvement with design. We were architects, Eleni was working the arts, I was working in architecture. We had some commissions and we started working in architecture. But then organically we started building some furniture and objects, not as a line, just playing around, experimentation. So many of our friends and colleagues, they started seeing this stuff, they said, “Guys, these are nice. Why don’t you keep doing this?”

So without officially launching a design studio, we started making more and more and more, and we found some fabricators. We were working in Greece and in New York as well. And then at some point during 2016, we officially thought of the name Objects of Common Interest and launched an official studio, in parallel with the architecture. Where the same people working the same projects, but just have two identities so we can run in parallel without interfering in scale and in complexity and schedule of work.

And if you had to explain to somebody today what is the signature of Objects of Common Interest and explaining this sort of aesthetic to a stranger, obviously I feel like I could explain it a little bit, but I would love to hear from you guys how you describe your work in a sense, which just sounds very … It’s a very basic question, but I’m fascinated to hear your answer.

LT: If I would answer this question, a characteristic that I think we both agree is true is that we don’t have a specific aesthetic identity, meaning we don’t repeat the same idea, the same formal expression, in variations. So every time we start a project, it starts from scratch almost. It’s a new thing. We start with sketches, with experimenting with materials. Many designers and artists, they have their thing and they multiply it and they make variations of it. We’re bored of doing this, we want every time to challenge ourselves and do something new.

And over time, this became our aesthetic identity actually, because it seems very disconnected from project to project, but there is an underlying idea that’s a bit more blurry in our minds that sometimes it comes out in the work clearly, but sometimes it’s very vague. If we were to describe, we work with abstraction, we’ve mentioned many times in other interviews that in terms of taking something that’s … There is a formal expression of it, but there is a concept behind it that it makes it intentionally abstract, intentionally ambiguous of what it would be. Sometimes it’s a stool, sometimes it’s a seat, sometimes it’s not specific. And in that sense it blurs the boundaries between art and design, utilitarian and non-utilitarian.

EP: Along the way, we realize that an underlying concept in anything we do, it’s about creating feelings. In our conceptual conversation, we have the two of us, we have with our studio, is about what are we trying to succeed? Meaning, we’re welcoming people, welcome audience to experience our objects, our installation, and we always want to leave an open-ended selection of feelings. So it’s about always inviting someone to, in a way, stop for a second and have a feedback, let’s say, to our work.

And why do you think that’s so important?

LT: Because we live among objects and they’re meant to be interacted with. It’s not something you’re looking from a distance, it’s something you touch and something you want to have next to you in your house, in your office, in your domestic environment. So it’s a relationship.

And that’s also something we have a connection through our personal life, we get connected with objects that we collect or with objects that we have inherited from our families or with objects that we live with. We’re very connected with the things we live with. And that’s the way we think about the object we design, that people will make a special connection with them. And when it comes to clusters of objects, when they become installations, where they become spaces, then it’s even more important because they define the way we live among these objects.

EP: To me it’s even further personal because my grandfather was a design collector. He would just travel to Italy to bring in the six and the seventies design object. I don’t remember him because he committed suicide when I was six-months-old. So I have the memory of my grandfather and grandmother through objects. So I established a very interesting relationship with obsessing with design objects or element … That they’re very important for me because for me, this symbolize the connection with the story, which is my grandfather or a trip that he made.

So taking that into making objects for us or elements or installation, we believe, as Leo said, much further that it’s a strong relationship there. And it’s not something we buy and then let’s go buy the next one, let’s go buy the next one. It’s about creating this relationship and the stories and establishing memories.

How do you guys, as a couple, you’re a married couple, you have two kids, what is it like in your life? How do you guys operate as a studio? Because you bounce between Athens and Williamsburg, two places that probably couldn’t be more different, or maybe they are, I don’t know. Do you guys have a division of labor in terms of like, is one of you better with sketching and one of you better with materials or vice versa, or how do you guys like to work together?

LT: It’s actually very organic, very, we have separation between us and Eleni, so especially between the architecture studio and the design studio. So we have a clear separation there. We always start together by thinking and conceptualizing and running a strategy if… We don’t really do a strategy, but no strategy on how we will think of a project. But there is no standard. Most of our team is in Greece. We have two studios in Greece, the fabrication studio and the office studio, and we have a studio here. And we are on the move as well, so we are constantly in communication, casually, between us, between the team. Sketching, sending sketches informally, but at the same time also having formal meetings and visiting the studio there. So there’s not a standard way of working, actually. But when it comes to starting production of a project, then things become efficient and very clear. Who runs the production, who has the decision making? After we have finished, let’s say, the creative part of a project, then it’s a production line.

EP: If you see someone how we live and how we work, I think it’s going to look a mess. But there is real structure there. As you said, we have two children now. One is five and a half and the other one is one and a half. And we have a strong belief that if you want to spend some time with your children, you have to adapt on that, otherwise they’re growing up completely independently from you. So right now it looks very messy, but it’s not. We have an amazing team with brilliant architects, curators, and other people that we are all very synced on how we think. So that makes things more smooth.

And so we jump between Greece and New York, we jump between studios, we jump between projects and scales. But all this happens very smoothly and organically. I think it arrives from our personality as well that as Leo said, we cannot multiply one thing in larger scale, smaller scale, different colors. Every project, it’s a starting point for us. It’s a new project from zero, and we start brainstorming, sending ideas, they start being developed. So it’s a very inspiration moment for us. The kids and the way you see a young human being, building their taste or their interest, it’s very intriguing for us because it has to do so much about the space we are creating, spaces we’re creating or spaces we live in.

And do you think that there’s an element to an American audience or to a New York audience? Do you think that there’s anything uniquely about the way you think about design that is Greek, specifically?

LT: Greek? There is always an influence, but it’s subtle. It’s in the back of our minds. Sometimes we bring it out with more immediate reference. For example, we did this project with Quadrat that we presented in three days of designing Copenhagen, I think two years ago. It was two big full scale Doric Greek columns that were rotating compartments with father fabrics that were spinning around doing crazy shapes. That was a project, it was an open brief that we brought in a Greek reference of the Greek column, something iconic, but it was intentional, came from us, this idea of iconography, of the Greek reference.

But most of the times it’s, as I already mentioned earlier, it’s a feeling, it’s something abstract. It’s memories we have of spaces, of landscapes, of the sun, of more vague ideas that we bring in the work. Sometimes it’s not visible to anybody, but to us, we try to describe it through a conceptual text, but there is always a reference that, at least in our mind, comes from our cultural background.

EP: If I can add to that, my main idea when we create an installation or a public project, I always have in my mind the feeling that you have when you walk down a small public plaza in a Greek island in a late afternoon or an evening. There is this, it’s a feeling of relaxation, of subtle happiness, of calmness. That is always stuck in my mind when I am thinking of inviting people experience something that we have made. So, yeah, it cannot go more Greek than that, I guess.

LT: Also to add to this is also from this, Eleni’s idea comes that our obsession with the tactility and with materiality that people can touch what we do, we want people to interact, and also a sense of warmth. And that comes again from I think Eleni’s references of the Greek island squares. When we create space through objects, we don’t want to just have a monumental or a cold environment, we want to create intimacy and warmth.

And if a design critic were to go and visit one of your shows or see one of your public installations and describe the work in a specific way, I’m curious, what is the worst way, in your own mind, what is the worst way for someone to describe your work?

EP: Instagrammable.

Oh, why?

EP: So I love Instagram and I believe it’s a great medium of someone expressing their personality and the people’s presence of documenting our work in Instagram or social media. It’s spectacular and I loved it. I’m so many times I’m requesting from people I don’t know, documented videos or pictures and I love them and I keep them for our own website. But I feel that critics or journalists, sometimes they use this term and that can be sometimes so shallow. So we don’t want just people come in, take a picture and go. That’s the least we want to do. So we want people get intrigued or people go around, people kind of trying to test or see or hate it or love it, it’s up to them, but just try to explore further than just get in, take a snap and go.

And Eleni, you speak about your work wanting to evoke emotions. What kind of emotions would you like to foster in your children about your work so that if I interview them 20 years from now, 30 years from now when I’m an old man and I said, what kind of emotions did you learn being the children of Leo and Eleni, what would you want to say?

LT: If I can add something, most of the emotions that we talk about and they come from memories. So memories create the emotions. And I think what at least we’re trying to achieve with working and living with our children and our work organically is that we want them to build memories of us and them together with the work. And that will, as Eleni talks about her grandfather, that will develop their own feelings about what they’ve been experiencing.

EP: To me, it’s the word inclusion. So we have them everywhere with us, we let them use everything. Our studio is their studio. It’s about including. And one message we’re trying to pass to them through our work, through the way we live. And the way we work is about including everyone, that our work is for everyone. It’s for them, it’s for babies, it’s for elders, it’s inclusion. Funny story is when we had the exhibition at the Noguchi Museum, one of the rooms we have been asked by the curator to create an ideal dream lounge environment. And in there was our tube chair. And the last day of the exhibition there was, someone was asking our son, “Oh, do you have this chair in your house?” And very casually, and he was at four at the time. He was like, “Oh no, not my home. I have it at my studio.” So he feels part of the process and I think that what we wanted to succeed and we feel happy about.

(SPONSOR BREAK)

My next guest is taking one of the oldest and most revered corners of art and design and turning it on its head, Lucia Massari. Born in Venice and trained at the Royal College of Art in London, under the eye of our former guest, Martino Gamper, actually, Lucia is working, as she puts it, to de-sacralize glass. You might know her for her series of adorable, yet fragile, clown like mirrors or for her bulbous vases with painted giraffes created for Dolce & Gabbana Casa. Or for cabinets covered in glass on all sides in colors like blue, orange, pink and green. I caught up with Lucia from her hometown to speak about her work that’s even more radical coming from the native born daughter of Venice, where her whimsical ideas come from and why she couldn’t resist the pullback to her native homeland.

Tell me a little bit about your upbringing because you were raised in Venice, but I was wondering what your earliest memories of life in Venice were?

Lucia Massari: Yeah, yeah. I mean, I was born in the main island. I was born in Venice, and Venice is divided in six areas, and one of those is called Castello, which means castle. I mean, because there was a medieval fortress there. So if you actually compare Venice to a shape of a fish, Castello would be the tail. The funny thing is I’ve been raised one bridge distance to where I live now. So it’s kind of funny that my kids are playing in the same campo, going to the same school that I was going to.

Wow.

But I was raised pretty much wild as we are a large family and I was very independent since childhood. Also because Venice at the time was quite an easygoing place to live. So I was just going around at quite, at a young age. So I think I remember one of the best game I was playing as a kid was just getting lost and also-

Trying to get lost?

Yeah, yeah. But I always find a way somehow. I also remember very fondly spending all the summertime on the boat, like swimming in the lagoon and drinking a lot of very salty water, all this kind of thing. And I think the slowness of the water in the canals, really, it felt like the time was just going slower than the other time zones somehow.

Yeah, exactly. And so at what point did you kind of decide to go and study design?

Well, I always wanted to be a designer actually since very early age only. I just didn’t know that it was called design. So I studied design in Italy first. I had my degree in Treviso. I mean, it was just a good school. University here are very academic. You study a lot, you study history a lot, but you never really get dirty. There’s not much space in experimentation.

A lot studio practice kind of stuff.

Yeah, exactly. Exactly. So once I graduated, I really wanted to go to London, the Royal College of Art, because I think it was just one of the best, I think still worldwide I think is one of the best. So I just really wanted to be there. And once there just got in, to me, it was just magic. But I was really, really rough. I mean was really, really at the beginning I actually didn’t know what I really wanted to be and I really spent these two years experimenting what I wanted to be.

And I really don’t think they were really successful years. And also they were pretty tough really. They felt like five years, but they definitely really shaped me. They gave me depth, they help me question myself all the time. And I think they kind of forced me to search for the answer when the process of searching for the answer was the answer itself. And I was extremely lucky to be able to have tutors like Martino Gamper, Jurgen Bey, they really opened up my vision. I was just incredibly lucky. So once I graduated, I then decided to stay in England as London has a really great design scene. But then eventually, I got called for few residency and all of them, they were just back in Italy and just few of them even in Venice, which was really strange to me because it was a place where I really was just running away from because I didn’t feel like it was my place, was really helping me to shape my interest in design. But I think all this occasion were really crucial to me to get closer to this craftsmanship, to the work of artisans. And I think back in England, the work was not the same thing. So I really missed the skills that actually complemented my work. During one of these residency, I worked with glass and then I just eventually returned to Venice permanently.

Did you experience any reverse culture shock when you come back to Venice and try to work there once you had experienced life in London for a few years?

Well, it’s definitely a huge gap. It’s a huge gap between Venice and London is just like, I don’t know how many centuries goes by. My culture and especially Venice, that even though I feel very distant somehow, I believe I have so much attachment to everything that is connected to it. So I really have this hate and love relationship. And I don’t know, I just didn’t want to stay in London for longer. I know that I needed to be here anyway.

And for the past couple of years, you’ve had some work and furniture and other objects and now it’s come more and more back to glass. What spurred that kind of return to, I guess you could say the family business, in a way?

Well, I don’t know. I think it’s true that I had this change in, but it’s kind of funny to me considering I didn’t want to work with glass at all. I mean, I really felt very distant to this material. I just didn’t want to do it due to probably the weight of the family legacy or historical significance of this material. I just didn’t want to have this weight on me. I just didn’t feel like any connection to it. But then eventually when I started, I was already seduced. I was just trapped in the trap.

I have this feeling that I didn’t choose glass deliberately. I really didn’t want to work with it. I mean also I rejected it somehow, but then glass found its way to me independently. I just believe that every designer has his own material, the kind of material that engage them more than other materials. So I just find glass very stimulating. I think it’s a material that I found really easy to work. And I also, over time I became very passionate and it’s a material that helps me to express myself much better than others. And I understand the nature of it. So once you understand the nature of material, then you can be really free in experimenting, you understand it, then you are free. You just go deeper and deeper and you are just free.

And you told Architectural Digest in an article that you felt the need to desacralize Murano glass. Can you explain a little bit about what that is and what do you mean by that?

I mean, this is part of the reason why I didn’t want to work with glass because I found it really challenging. At the beginning was just very, very difficult to detach myself, envision as a fresh perspective on the meaning of contemporary glass. Also because Venetian glass, it carries this own distinct aesthetic. It can be also very overwhelming to consider that there’s so many artists, so many people have been working with this material in the past. So I also felt that somehow everything was already been done. Everything was already been accomplished.

It also very, very difficult to engage sometimes with furnace. I mean, if you self produce, then you really need to have a good amount of money to make your peace. I really feel like, and I always felt it and I think really I feel very, very fortunate because I really feel that it’s a luxury being able to approach this craftsmanship. So I really felt like the only way that I could work with this material was just to navigate around it to find my own way. And I think irony is the best way that I found to circumvent, you know what I mean? So the sacralizing and the mythologizing, that’s what I said, just way to make it also visually accessible somehow.

And when you were creating your designs, whether it’s the mirrors or the chandeliers or anything like that, and you’re using a contemporary language and a youthful language, was it difficult to find producers that wanted to, because your work also looks quite complex too, at the same time. It’s not like it’s simple at all. So was it hard to convince a furnace to work with you and did you have to navigate that or were they actually excited to do something totally different?

No, I mean they’re quite open. Once you pay, there’s really not a problem. They’re quite open for this, I mean, actually over time they learn to work with artists. And I think working with artists is kind of easier than designers in a way, because designers have this specific idea on how the materials should behave. You know what I mean? So they make this specific drawing most of the time, like 3D, AutoCAD or Rhino, they go there to the furnace and the maestro, the master say, just take your pencil and just draw it on a piece of paper because they’re not used to. That’s probably the reason why I love glass a lot because I don’t require specific skills, specific 3D skills to make my idea just grow, and I think they’re really open to it. I would say they are born for that. They can just translate every ideas and everything. They’re really good at it.

And when it comes to your specific, the designs that you’ve been doing for the past five or six years, where does the ideas come from for these shapes? What is your creative process? Is it just from your imagination or where did these… because they’re very cohesive, but they’re also very unique and original. So I was wondering if they came from a particular place or if it was just something that you maybe from your illustrations or something like that.

Well, some of them comes from illustrations, some of them comes from colors. I think I would say since I started working with class, I think I start actually to experience some synesthesia. When you have certain colors evoke specific memories or materials trigger childhood recollection. I think it’s the reason why I like glass. I don’t know, I think it has a annoying human attitude, it’s own wheel that is very kind of, I would say pushy, intrusive, persistent. It has this kind of characteristic that I appreciate actually. So I always seek for glass to express itself and contribute to the final artwork. So whatever I have, I envision a shape. I always leave a portion of the material to contribute to the final form. So no matter how much I try to manipulate the material with a certain technique, the material as always a language that sometimes really suggest the vari forms.

So it’s really true, I could actually work on shapes. Also when I start working with this company, which is called Barbini Specchi Veneziani. So the more you go deep into the craftsmanship, the more you start to think of different way of using the same craftsmanship in a way that suggests you shapes and alternatives to what you want to express. So I think it’s just like everything comes as a chain, one after the other, and then glass does the rest.

If I had to ask my last question, if I had to ask you what you felt, how you could define your work and the purpose of your work in one sentence, what would that be?

I normally ask people to define it. It’s just too difficult for me probably because I’m so into it that I really… I don’t know, I think I’m kind of color driven a lot. I think my work is very much connected with color. And probably this is another reason why I think I love glass quite a lot because glass really reflects light and light is the essence of colors. So most of my work really, it’s all about using glass as a moldable color. So I could just describe it as color something, because I really think a lot of my work really has a lot of a strong connection with colors.

Could you live in a house without any color?

I would never. I would never. I would die.

(MUSICAL BREAK)

Thank you to all of our guests, Tom, Eleni, Leonidas, and Lucia and to our sponsor Lumens for making this episode happen. The editor of The Grand Tourist is Stan Hall. To keep this going, please follow me on Instagram @danrubinstein to learn more and sign up with your email for updates at thegrandtourist.net. And don’t forget to follow The Grand Tourist on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you like to listen and leave us a rating or comment. Every little bit helps. Til next time!

(END OF TRANSCRIPT)

The newest gallery openings this week, including the dark side of the American dream, traditions of Aboriginal Australian painting, a cheeky photographer, and more.

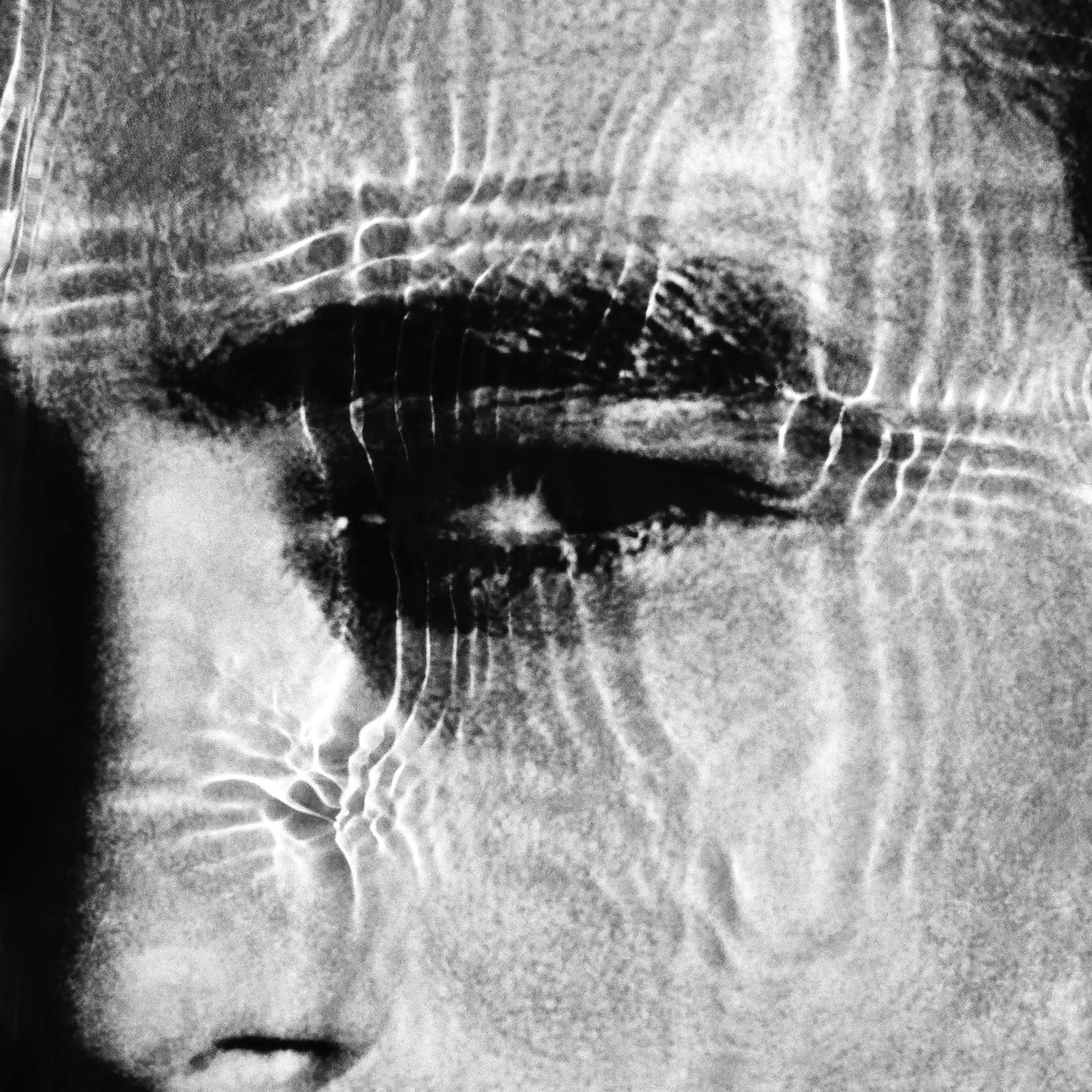

For Italian fashion photographer Alessio Boni, New York was a gateway to his American dream, which altered his life forever. In a series of highly personal works, made with his own unique process, he explores an apocalyptic clash of cultures.

Plus, an exciting young British artist receives a retrospective, Marcel Dzama's whimsical drawings take a political turn in L.A., and more gallery openings.