Annie Leibovitz Shares Her Vision in Monaco

The newest gallery openings this week, including the dark side of the American dream, traditions of Aboriginal Australian painting, a cheeky photographer, and more.

Designers Robin Standefer and Stephen Alesch are a true power couple in the world of design. Through their wildly successful firm Roman & Williams, they have changed the visual language of hospitality through their projects for hotels like Ace Hotel and The Standard, and with their own product business, RW Guild, they’ve influenced how the well-heeled think about home. On this episode, Dan speaks with the duo about how they met working behind the scenes in the film industry, their breakout projects in New York, plans for the future, and much more.

TRANSCRIPT

Robin Standefer: … Like I always tell the story of the Rizzoli book and Charles Miers, our publisher who’s amazing, we wanted to put pictures in that had the Boom Boom Room picture was on New Years Eve and had balloons and half-naked girls and all kinds of wild business. And he’s like, “Interior books don’t have these pictures.” And I was like, “But they should because the spaces, it looks like everyone’s dead in every shelter magazine. Where are the people? Where’s the life?”

Dan Rubinstein: Hi, I’m Dan Rubinstein and this is The Grand Tourist. I’ve been a design journalist for more than 20 years, and this is my personalized guided tour to the worlds of fashion, art, architecture, food, and travel. All the elements of a well-lived life. Sometimes in the world of design, projects don’t just make a statement but ship the culture in unexpected ways. It’s a bit like the so-called butterfly effect, where in some sci-fi time-traveling epic, someone steps on a bug 1 million years ago and all of history shifts to create a radically transformed present day. My guests today through their rich, tactile and considered work, have made tidal wave changes to the aesthetics of the present, through their products, hotels, restaurants, and exhibitions, Robin Standefer and Stephen Alesch of the firm, Roman and Williams. Partners in life as well as work, the two met working in the world of film behind the scenes and after created homes for some choice celebrity clients.

They eventually sat out on their own to bring a soulful, handcrafted ethos to the real-life interiors world when it may not have been as much of a buzzword as it is today. To me, their first major impact on design came into shape with their hotel projects, two of which they worked on at about the same time, including the original Ace Hotel in New York. Not only did its design make waves, but how it was used became a shorthand for a whole new way of thinking about hospitality. And the Rooftop Club created for the other hotel that I mentioned that would be the now legendary Boom Boom Room at the Standard Hotel on Manhattan’s West side, which is now shorthand for nothing less than a really great time.

Roman and Williams have gone on to create spaces around the world from Tokyo and London to Istanbul and Miami. No matter the destination, they always bring their opulent A game signature. The Financial Times called them luxury’s default designers of atmosphere. And since the firm’s inception, their presence has been felt more than most masters of mood indeed. Robin and Stephen could probably just have made incredible hotels, restaurants, and private clubs forever with some other high-profile works sprinkled in like the redo of the British galleries at New York’s Met Museum or their private client work for the likes of Gwyneth Paltrow and others.

But around 2017, they started a journey into retail called Roman & Williams Guild, that became a major success and later spawned a sister art gallery called Guild Gallery that champions the duo’s favorite talents with a special emphasis on earthbound materials like ceramics and glass. Of course, they’re not stopping there. The pair is now venturing into the world of lighting, which we’ll speak about. I caught up with Robin and Stephen from their house in Montauk to discuss their contrasting backgrounds and how the duo met, how their hotels shifted, the conversation, their creative process, how Ben Stiller factors into everything, and much more.

Thank you guys for doing this and for joining me today, and I’m so thrilled to talk to both of you. But I kind of want to start at the beginning because of course I know you’re incredible firm and many of the things that you’ve done. And Robin, I believe you grew up in New York, and Stephen, you in LA. And I’m kind of wondering what kind of memories define your early life. Stephen, let’s start with you.

Stephen Alesch: Well, hey, I was actually born in Wisconsin and kind of grew up early years in Milwaukee in this sort of inner city Milwaukee in the seventies. And in third grade, I think it was a summer between second and third or sometime, it was kind of a foggy… My mom packed us up and we moved to California. 1973, I had two brothers, so one of three brothers and she just left on her own, no dad. And we moved to the hills of California, which was pretty fun at that age. I was pretty happy. My brothers too, we loved it. We had a beautiful house up in the mountains, kind of Malibu Canyon, the sort of hippie hills I call them because my mom sort of fell into the new age movement at the time, vegetarianism and meditation. And so she said, “Let’s get out of Wisconsin.” Hot dogs and factories and cigarettes, unhealthy living, drinking beer. And California was just like land of health food, carob, grew our hair long, just became free-spirited, kind of hippie kids. It was fantastic. Started surfing at that time.

Okay. Do you still surf today?

SA: Yeah, I still surf. Still love it. It’s a big part of my life. And one of the reasons we came to Montauk was because of the waves. And sometimes Montauk has a little bit of a California vibe, but if you really kind of squint your eyes and kind of ignore certain things, it feels a little bit like central California sometimes when you’re on the hills and cliffs and waves are great and not as many surfers as California, so it’s pretty nice.

And Robin, what about you? Are you a New York kid?

Robin Standefer: Yes, I’m a New York kid, although I love hearing Stephen’s story because I was always fascinated by California and Californians, as many New Yorkers are, whether they want to admit it or not. And that sort of brought us together. But I did grow up in New York, born and raised a couple of generations and just was really drawn back there, which is why we still live there. My parents still live there. They’re on the Upper East Side now. They were on the Upper West then. Just was a real city kid. I mean school bus, subway, uptown, downtown.

My uncle lived in the Village, so I loved being there and even going to high school in Manhattan at Art and Design so that it’s a very particular way to grow up because I think at a very young age, you start to have a connection to the city and a exposure to things. It’s very different, I think, than having a rural upbringing. So just watching the gallery scene and being 16 and meeting Basquiat and just that to me, and people are always like, “Ooh.” But that was just normal. And New York was pretty gritty then and amazing, but such a kind of powerful stomping ground and so much going on. I remember being on the school bus and those are just city things that are very particular.

And Stephen, being in LA, did your family have any connections to the industry or to film or to Hollywood or anything like that?

SA: Yeah, that’s a great question. It’s sort of natural living in Los Angeles area where you sort of stumble on it. Because I remember as a little kid, we would watch… Films would come to the neighborhood down the street from our house. They would film like Bionic Man or different movies would show up and I’d watch all the trucks and everything like that. But growing up, after high school, I went right into drafting in an architecture office just with high school education, believe it or not. I was a really great draftsman and just with a little role of drawings. I got my first job really early, but I worked in architecture pretty much my twenties, pretty young. I think I was 19 when I started in office. But my stepfather did still photography for feature films as a job, one of his many jobs, but that was one of them.

And he had a couple friends who were art directors and things. And sort of in my late twenties, I was, to be honest a little fatigued by architecture because I started so young, I think like a Doogie Howser kind of situation where I was already tired of it by 27, I was exhausted, 28. And film kind of… My stepfather introduced me to an art director. I showed him my drawings. And my architecture drawings, I do pretty serious working drawings in architecture, but I always did presentation drawings and sketches too. I’m a really good quick sketcher and that caught their eye and they were like, “You have absolutely have the skills to work as a set designer and work with directors, sketching, sketching with them in real time.” And I packed my bags and just went on a wild film in my late twenties and did that for about 10 years. It was kind of a longer story, but…

And Robin, what about you? What was your first entree to design and film?

RS: Well, I think that going back to the earlier question… I mean, both Stephen and I have these really counterculture hippie moms that were very independent and raised us in a way that was about being just very open, thinking and believing we could do anything. And I think that’s a great way to grow up. And so I think this sense of artistic spirit in whatever it is… I mean, even to this day, I never think of design as having such a formal definition, but I think about it as part of curiosity and having an artistic spirit, so I don’t totally know the answer. I was always interested in painting and drawing. I was always a compulsive object collector, whatever it was, still am, small and big. And so that lust and desire just led me down the road of art and fine art and trying to figure out how to turn that into something professional. But I think this a book end of almost this whole interview, the idea of this sense of curiosity of making things and building things at whatever scale led me to film and to design and to-

What was your first job?

RS: Well, it’s funny. I don’t totally know the answer, but it might be… I was trying to think about this today, and this is just about getting older, so you don’t remember everything-

SA: Your first film job

RS: I think. Yeah, but my first job-job was a combination of working the door at Castelli Gallery and working for Robert Lee Morris at Art Wear, which if people don’t know, that was the epicenter of Soho. There was all these crazy artists casting and making all this jewelry and then Castelli represented like everyone and that those were my days. And it was really, you just got exposure to such an incredible group of people and there was just so much energy and creativity. And film was a natural evolution of that. I mean, working in fine art and painting, somehow I knew that I actually wanted more.

I think I was too interested in so many different arteries to want to just singular and be just a painter or an artist in that sense. So film was the beginning of this wild Gesamtkunstwerk collaboration, like one everything. And so I was pretty young, I guess just out of college started to work on an independent film with a friend who was like, “Why don’t you work on a film and you do everything?” I did wardrobe and I went to a laundromat to wash people’s clothes and made the sets and it was just really invigorating and amazing. And I also loved the story-telling. I loved the idea that it was a combination of this creativity of making space and telling a story.

And when did two of you first meet? Stephen, do you remember that day?

SA: Yeah, the year gets a little fuzzy, but I was working in Los Angeles on films, film after film. I was just sort of a hot shot set designer, just answering my answering machine at night after work and taking calls for next projects. Most of my film projects lasted from four to eight weeks. I’d be on a gig way, before shooting. I was never around during shooting. I was doing the prep for it, but I was working on a project called Cabin Boy, drawing a big boat in a soundstage. And the same person, Mark Zulewski, who had originally got me my first film project, my stepfather’s close friend, he says, “Hey, there’s this production designer from New York in town. She’s looking for somebody to come and do some sketches and draw, but you have to meet her at night. You have to meet her at 7 PM.” And I was like, “That’s fine.” I loved moonlighting, so I was working in Valencia, which is an hour outside of LA and then I had to drive into Hollywood to this location where this so-called New York production designer. It’s all really told me.

He said she was intense, but I was kind of excited. I loved New Yorkers and there wasn’t a lot of them in my life at that time, but they were kind of a exotic animal. And I went to this little funny junkie office in Hollywood. It was a low-budget film. I was working on kind of big budget stuff, so I was a little spoiled. But I go to this small little office, but it was just so cute this office because it was just desks all over the place and then Robin had made a little corner office that was just decorated really beautifully with drapery and vintage lamps and stacks and stacks of books. But she wasn’t there. She was super late. She was an hour and a half late, and I sat in this little room, this beautiful little room. I was kind of fine because it was like seven, eight o’clock, and I just was flicking through all these world of interiors.

It’s when I discovered world of interiors while I sat there that hour and a half. And I’ll never forget it because I was looking through these things… It was like eye candy. I’d never seen anything like this before. I’m like, “Oh my God, it’s like a research Bible and this room is so beautiful.” Then she comes storming in, this small girl, black hair, very gothic, kind of New York gothic, kind of energetic, very pretty, super smart. I was just like, “Oh my God, who is this? Who is this?” And so we spent a couple of weeks together working in nights, sketching, bonding, talking about everything. It was really amazing experience, and it was a movie called The New Age. Ironically enough, we were working on a set of a store. It was kind of a funny thing.

On Robertson Boulevard, if you know LA, we took a empty space and I did sketches and for this really highly developed, very intense lifestyle store for the background of the movie called The New Age, kind of a dark story. Michael Tolkien was the director, but that was of our bonding moment. It was a couple of weeks together and then we said goodbye, but we both had complicated lives and relationships and things like that. So it was really a professional relationship, but we were definitely checking each other out in a serious way. She was a little over my head because she was so smart and so mature, and she lied about her age too because we were both in our late twenties, but she said she was like 35 or something. I was like, “Jeez.” And you’re…

Oh, she told you she was older?

RS: I had to do that to get the job because I wanted a production design. It was just such an amazing day. I had been working with Scorsese, which was incredible. When you did film in New York and I went from a… As I said, I did that short film and I got some work with him, which was phenomenal and being around all these amazing people. But I really wanted… I kind of missed, strangely enough, these low budget movies because you got to do everything and make everything. And also, even though working with Marty was incredible, there was always an aspiration to go to California. So first of all, of course, I was in New York City. I didn’t drive, so I had to get a driver’s license. That was hard enough. And then to be able to production design, you had to sit with all these cigar smoking dudes and tell them that you could design this movie, which I knew I could do.

And I had a great head for assemblage and putting spaces together, but I didn’t draw. I mean, I can paint and do watercolors, but in a really rudimentary way, not in an extraordinary way, like Stephen. So I go to California and I pitch for this job, and I get it. Nick Wexler, who produced Drugstore Cowboy was an incredible guy and just believed in me, and he was this kind of person who was really open to younger people, and I always looked a little younger. I’m kind of small. I was always the shortest person in the class. So I was like, “Okay, I have to lie about my age.” Which of course, 10 years later I was like, “This is a bad idea. I have to stop.” So Stephen and I were together for four years and I was like, “Oh my God, on my birthday now, I have to tell him how old I really am because I’m going to stay with this guy and this is not going to be good.”

Anyway, we had this office. It was next to Pink’s Hot Dogs. I had a giant Ford Granada that I was terrified to drive and a brick phone, and this was California for me. And the California I imagined was surfers and meadows and just this California of my dreams that then in walked Stephen that… I didn’t even know, but I somehow sensed it that he represented that. And so he was there sitting in my office, totally adorable. The first thing I saw was this beautiful spread collar shirt and these perfect weird boots like worn in perfectly. And I was like, “Okay, who is that?” And then he just opened this portfolio of drawings and I just will never to this day forget them. I was so moved because I’ve always been really enamored with just that level of traditional technique and artistic skill. It’s still a fundamental of the guild and everything we do. And I’m allowed to say this, I’m his business partner, his wife, but just there’s just maybe like, I don’t know, three people on earth who have a hand like Stephen’s. And walking into that room and seeing those drawings, it was a seminal moment in my life. And we did, we had complicated life, but it was almost beyond that. It was about this artistic connectivity and I don’t know, the rest is history. We started to work together.

SA: Nature, right? I think I took you to the beach or hiking. I was never really at Los Angeleno because it was too concrete for me. I had a Jeep or something and I was just sort of country style. It was kind of my thing, like carrying around wild flowers and stuff like that. Dried flowers in the car, you know what I mean? And Robin was really, she came up to my apartment and there was just flowers everywhere and drawings of flowers and drawings of plants and she loved that so much.

RS: Oh, game over.

SA: And we bonded over pods. We were big on pods. We would go pod collecting.

Like pea pods?

SA: Yeah, pea pods. Any kind of big wood pods from our favorite pod was from this one tree called the bottle tree, the Australian bottle tree, not the bottle brush tree, but it’s called a bottle tree. It’s got these giant woody pods and there was a… 11th Street in Santa Monica had a, 10 of these trees and they were kind of low hanging down and we went and collected them and she’s just going nuts about the architecture of these pods. And then just to kind of play her, I would do a… next day, show up with a drawing of the pods, give it to her or a watercolor of the pods and just that was sort of pod flirting.

RS: Pod flirting. That is it. This is basically the basis of the relationship. I remember, I still have the pods. I still have the drawings.

SA: And for a birthday present, you’d give me like a giant pod.

RS: I would press a lily flower from a walk we took. It was all that. And I-

It’s like the history of a costume drama or a romance drama.

RS: I guess, a really pretty romantic attitude, very focused on nature. And I always had this, again, love and devotion to nature. I grew up in New York City, so it was really nature culture. So I found that through paintings at the Met or stuff at the drawing center, like drawings I got to see or objects, sculpture, but not a Louise Bourgeois, but not really experiencing it to that degree. I mean, look, we garden a lot now. I mean Steven sometimes makes the joke. I’ll make it for him, “The first carrot ever saw was at-“

SA: [inaudible 00:21:45].

RS: Thank You, honey. “The first carrot I ever saw was at Fairway.” I thought that that’s where they came from. I really-

SA: No, the funniest thing is when we were early gardening, I pulled a carrot out one day from the ground and she looked astonished. She was like, “What the hell?” And I was like, “What? It’s a carrot.” She’s like, “I didn’t know that they grew up underground.” And I thought it was the cutest thing I’ve ever heard in my entire life because it’s like you don’t really know when you’re going to the grocery store, right? You’re not growing, pulling carrots out. She’s like, “I thought there was a carrot bush maybe, just this beautiful bush that these orange things grew on it.”

Oh, no. I was just going to say, and the jump to residential design and the jump outside of the film industry started with a particular house you guys worked on together. Is that true?

SA: Yeah. Yeah.

RS: Yeah.

SA: We didn’t know it was our last film, actually we were on a film called Duplex in Los Angeles, which is an amazing film, set design wise it was pretty amazing. I don’t think the actual film did that well, but it’s a little noisy and starred Drew Barrymore, Ben Stiller buy a brownstone, and as they peel away at a partition wall, they start to discover all of this, what it says in the script, it said pure architectural pornography, which translated to elaborate Tiffany aesthetic movement, wall paneling, corbels bracketing. They just peel away, they discover that they’re living in this incredibly detailed brownstone and they start getting really, what’s the term for it, Robert? They just start getting lusty to take on more. They want this next department above them and they try to get this old lady to move out and take over. We built this whole set from scratch on a soundstage in LA and Ben Stiller was the actor and he wasn’t a director.

We knew him because we had done the sets design for Zoolander that he directed and starred in it. So we were actually kind of friends with him, like first name basis. But he shows up to date a shoot in this brownstone set that we made. We hadn’t seen him for a year or so. And he walks in and he’s like, “What the heck is…” Like, “Oh my God, you guys have lost your mind.” Because he’s looking at all this carving. We had made fireplaces and plaster relief with peacocks and stained-glass. He was knocking on the wood, knocking on the plaster. I’ll never forget it, he says, “This set is more real than my house. My house is fake. My house is completely thin and fake. This is totally real.” It was such an inversion of reality in that soundstage that day. And he’s like, “Please come to my house this weekend. I want to show you how bad it is.” And he’s like, “I have styrofoam crown molding in my house.”

RS: And he did. This is what I mean about the building arts versus film, and this is about us also breaking the mold. We were like, “Wow, there’s all these artisans. It’s the 18th century. Let’s use them to make architecture.” I mean even incredible, Denise Di Novi was a producer came and said, “You guys should do this in reality.” And go on, Stephen, about Ben, because this is the next step.

SA: I was just saying, for two years we basically redid his whole property and whole house, did additions, but we used a lot of film carpenters. We used the Disney wood shop for all of our carvings because these Disney guys, we could take a 12 by 12 10 foot-long piece of old Growth Oak, give it to these guys and they would spin it into a column in a matter of hours. We built 40 of these columns and bring them to Ben’s house and install them, done a beautiful arcade. Stuff that the normal construction guys were like, they didn’t even know how to do that. They didn’t know how to spin a giant post with a lathe.

They were going to go buy a Chatsworth fiberglass column down at the 1-800-Columns. But we were just doing this stuff from scratch and we had all this kind of manpower to do it and sort of naiveness about it. I mean, I had my architecture background from those years before, so I knew how to put drawings together and get permits and all this stuff like this. I knew the build department like the back of my hand. I was like, “Oh, I could go get permits for everything.” Did the drawings for those, got the permits, and then we supervised construction on the site for two years. And that was photographed for House and Garden, Robin, was it? HG did a piece on it, Alticor maybe.

And when it comes to your first, you break out on your own. You’ve gotten your new firm, you’ve got a couple of amazing projects under your belt. What were those first five to 10 years like in the firm? What were some of those-

SA: It was kind of a quick ramp up. There was a period we left LA because we found ourselves doing these celebrity homes. We did a couple. We did a project for Davis Guggenheim and his wife, Elisabeth Shue. She was an actress, and at Venice we did a place for them. And so we found ourselves, we were pretty happy with this celebrity clientele in LA. We were like, “Whoa, this was quick.” But we were a little tired of LA, at the same time… I had moved to New York in ’95, I didn’t ever mean to come back. Robin didn’t drive. She was like, “We got to go back.” So we go back to New York, we take an office, but we’re working on LA projects in New York. We had nothing in New York for a couple of years. We were doing the smallest renovations. I mean, I have elaborate renderings of a four-foot wide kitchen renovation for somebody in an apartment. We were-

RS: Oh, total hustle out of our living room. We first didn’t take the office. We were like, “This isn’t going to work.” We couldn’t afford to get our car back from California. But you stick it out.

SA: Yeah, we’re just doing small apartment renovations, really small. But strangely enough, we took this office. It was a little over our head rent wise, but we took it, and we had a opening party. Robin throws a really good party. She always puts a lot into it. So it was like elaborate party, just invited everybody we knew in New York. And one of the people who came to the party, believe it or not, was André Balazs, who we didn’t know, but we’d love the Chateau Marmont. We hung out there constantly in LA. He was a bit of an enigma, mystery to us. We used to see him walk by once in a while, but we never talked to him.

RS: And we knew Griffin Dunn who introduced us.

SA: Griffin Dunn invited him, and we knew Griffin pretty well. But André shows up to the party and he says hello really gently to us. And he loved our office. He loved our office. And he specifically loved, strangely enough he, he’s like, “Whose paintings are those in that back office?” I’m like, “Oh, those are my paintings.” And he goes, “Really? Hauntingly beautiful,” he said, and the paintings were of stars. I do all these black paintings with stars. And underneath the painting in kind of stencil font, I wrote, infinite tedium, beneath this painting. I think I maybe put it in Latin was like, “Tedium Infinitium,” or something like this, pretentious.

But anyways, André was taken by this, and it always struck me that he just loved this. I think another painting was tireless star. I had this idea of the star that never gives up. And a couple days later after this party, we get a phone call, and again, we’re doing the smallest projects, and it’s André’s assistant saying, “André wants to meet you to talk about something.” And we’re like, “What could that be?” And a couple days later we go to a meeting and it’s André at his office, fancy. And he sits us down and he says, “I’m looking for someone to be my partner at the Standard Hotel, a new ground-up standard Hotel on the West Side highway, the west side one, the big ground-up thing.”

RS: Highline. Yeah.

SA: And we had no hotel experience, right? But I think he saw in us this sort of vehicle that he was going to drive to success with that hotel because of our tirelessness and both of our skill sets. He loved my drawings, but he loved Robin’s energy.

Did he give you a brief or anything like that? Did he say [inaudible 00:30:06]

SA: Oh, yeah. We went to Los Angeles. We went on a tour of the LA ones with him, we have definitely a brief, André’s very-

RS: A big brief.

SA:… very hands-on. And as I’m drawing a line on a piece of paper, André’s following it with his eyes. You know what I mean? Like, “Where are you going to go next?” I mean we spent days and days and days with him. We became close friends. I mean we would go to his apartment with drawings, draw, draw, draw, sketch after sketch, redo everything over and over again. I remember drawing floor plans on the Standard after the third or fourth floor plan of the ground floor lobby. I was like, “Is this anywhere near approved, André?” And he’s like, “Approved, what do you mean approved?” I said, “Well, we’re just trying to get approval to move to the next step.” And he was like, “I don’t think it’ll ever be approved.” He just looked at me with these mischievous eyes. André never approved anything. It was always a work in progress. Always could be better. I mean, the guy is tireless, just like this thing, tireless star, infinite tedium. He will work and work and work at perfecting something forever.

RS: But just believes that something’s never finished. And at the same time, we were doing the Standard, we were working on his house. Right in Rhinebeck. Yeah. So we were doing both together. And it was sort of interesting working on, even that started with Ben working on Duplex, working on a movie and working on his homes. So we started to get in these very intensive-

SA: We took that bond with our clients pretty seriously.

RS: Yeah, intensively.

The Standard was a big hit. So what do you think from a hotel point of view, from a hospitality travel universe point of view, what did people tell you they loved about the hotel?

RS: Well, something very funny happened, which is that, and I think this and even we were working on Ace and the Standard at the same time. So I think that there’s something important to that part of the story because the fact is that the Standard was for a certain kind of cultural community. And the Ace was for a different cultural community. So what people loved about the Boom Boom room of the Standard Grill was the opposite about what they loved about the Breslin or the Ace lobby. And we had this moment of Eureka recognition that we were kind of more ethos than style, that we just wanted to play with our ideas about experience and culture like Stephen always said, punk and-

SA: Like punk and disco. Yeah, we always said that the Standard was like Gucci. The Standard was Derek Zoolander and the fricking Ace was Hansel. If you’re a Zoolander fan, I mean, we were talking about dirt… Ace could easily have had a dirt room in it. Could it not have had a dirt room somewhere?

RS: 100%, we should have.

Derelict, if I’m remembering the film correctly.

SA: And then of course the Standard, its André embodied, right? Good-looking, sexy, right? I mean that’s the side of us, we have that little side. We love that side. And then the Ace was sort of punk, a little urchin-y kind of bratty. We have that side too. And so we loved it. And of course they’re kind of like mortal enemies, Alex Calderwood and André Balazs, it’s almost like a comic book, like Batman versus Penguin.

Were you annoyed that you were working on the other while you were working on-

SA: Yes, for sure. It definitely caused friction. André was hurt by it. The Ace was a fast project, maybe one or two years design process and build. It was quick. Standard was six or seven years of hardware.

RS: Because it was ground up.

Right, of course.

SA: So it wasn’t the whole job, it was like the last year. But it hurt André’s feelings. He felt like we got pushed out a lot of the media and press at the end of the job because of it, made us feel bad too because we put so much into it and we learned so much from him. But I think five, 10 years later, we regrouped and became friends again, internship for his daughter at our office. And he’s still one of our close, close friends. We love seeing him and haven’t worked on anything since then, but he’s still a dear friend. And it all worked out at the end. And I think they really stepped… they never fought for the same customer. I think it was really apparent that they were totally different brands.

I guess maybe because I think my office was near the Ace at the time, to me, and I was maybe the right demographic. And to me, the Ace kind of changed the way that hotels were used and designed and people didn’t just… it wasn’t just a place to sleep, it was a place to hang out. People brought their laptops, they did meetings there. It was kind of an early place where that, quote, unquote, “third place” started to come into being-

RS: Oh, it was groundbreaking for sure. I mean, the Standard-

You couldn’t find a seat to have a coffee.

RS: … was amazing. People love the Boom Boom room. They still do. So that was just an incredible space. But it’s not like that was outside of a typology that we understand. The Ace, we broke the mold and Alex had that vision. And then this goes back a little bit to talking about Stephen’s kind of California background because it was a lot East Coast, West Coast, and it was about the West Coast kind of just casual ability to just be lighthearted about bringing things together and an East Coast kind of punkness. And those two things at Ace came together and we loved Alex and we were very close and Alex passed away, which still is painful to me to this day. And we wanted to create a hotel that was… just create a new definition and it was, that table that we made with plugs for laptops because laptops were a new invention. And so all of that, it was about also the fluidity of work and eating and all of that was one thing.

SA: That’s the thing we agreed on. Remember that too we all agreed on it. Money changing hands was not a heavy principle, say like a W Hotel or something where it’s all about selling beverages in the lobby. I mean the Ace of course had to make a profit, but Alex’s philosophy was about generosity. And you could camp out in that lobby and not really be told to leave or, “Hey, you got to order something if you’re going to sit here.” It wasn’t allowed. And I think that’s a very West Coast Portland style of generosity that he had and designed to be very comfortable where you could just camp out but feel no pressure to have to eat or drink the whole time.

RS: But a real definition of hospitality, a true definition, a clubhouse, just come hang out, a commune, talk about… We all had kind of Bohemian families and sort of forged our own paths. So Ace felt very comfortable in that way. I mean, I sourced all vintage furniture and it was like, “Let’s be inspired by Alexander McQueen.” And Stephen painted on top of a wing chair, spray paint on plaid. And we were just really loose and spontaneous and everybody was on the team. And specifically Alex had a great team, but me, Stephen and Alex were just… Wade was amazing, just said, “Okay, a hotel doesn’t have to be what you think it is.” And then doesn’t have to be the history of the Ritz, which is amazing, but can’t there be a new approach to what hospitality in a hotel is for a new generation? But just remember when it first opened, Dan, there were tumbleweeds. I was laying there on that sofa at Ace, that suede sofa that looked like Jim Morrison’s pants. And I was like, “Okay, no one is ever going to come here. This was a cool, weird idea and this is going to be our clubhouse, forget it.” And then suddenly…

SA: Yeah, a couple months, right?

RS: Oh. Slow, long months, many of them. And-

SA: The neighborhood was so quiet at night, right? You-

Yeah. It definitely was also the core of a new neighborhood too for a while-

SA: Yeah.

… that became the sun to which everything was revolving around. There was a restaurant and there was a shop, and there was things around the neighborhood, around the corner.

RS: But it took time. You have to take that kind of risk to break ground, to create a new idea. You have to be brave, you know what I mean? You have to stick to your guns. It was a great team to do that. We started, even for the rooms, designing all the furniture, playing with it in plywood, just it was a lot of invention. Having artists, finding artists, giving them 300 bucks to do a different piece of art. And every room we folded up canvas and sent them to them. Stephen made this track in the room that had pegs and holes for the art to hang on.

It was just really about just forging your own path and doing everything and having a community of people doing things on their own terms. And then even we were in the lobby and a bunch of folks from Facebook were like, “This is outrageous. Do stuff for us.” That started a new thread in our career.

SA: Yeah.

And when it comes to the Boom Boom Room, it’s super successful. Why do you think it was so successful? What about the design of that [inaudible 00:39:52] rooftop.

SA: I know. The Boom Boom Room, right, has-

To people that don’t know, it’s a rooftop space. We’re surrounded by windows with this incredible bar, and there’s this amazing column in the center. I’m oversimplifying but, I mean, it was hugely successful.

SA: The Boom Boom Room is-

RS: No, but sexy and glamorous, right?

SA: I think it’s rooted in its… Maybe it’s because I think of interior architecture is this most important thing. I think its power and beauty is because of its interior architecture. I exercised every bit of strength I had to draw that room up. That room is based on a lot of research, but some of the research was from the first architecture job I had back in the ’80s.

The first person I worked for was a guy named [inaudible 00:40:40], Iranian architect, who had just come over from Tehran during the revolution. He was a hot shot Tehranian architect who worked for the rich people of Tehran. One of the first projects I worked on was Prince Reza’s house with this architect. I was a kid, and I’m drawing these plans for this Prince Reza’s house in Virginia, which had waterfalls in it and disco clubs and three-story fireplaces.

I mean, the whole thing was like, if you can imagine Iranian modernism back in the ’70s, ’80s, and was pretty intense. I would say ’80s. By ’80s it ended, but ’60s, ’70s, ’80s’ Tehran was really intense architecturally, very experimental and things like this. I was drawing all these floor plans and details for that house, and I saw the house go up. We saw a couple houses go up in California with him. So, my skills with this modernist, curving, bending architecture, the trees, the wrapped columns came from [inaudible 00:41:47] and what I learned at that office at such a young age.

André was just blown away as we did sketches and prototypes and built samples of things. You never saw a happier person in the world. He was like-

RS: No.

SA:… “Yes, this is-”

RS: And he loved the references to nature. Because Stephen and I really didn’t want to use too much research that was other people’s work. So, between Stephen’s history of working on this really curvaceous, sinewy architecture coming from ’70s Tehran and us looking at trees and lays of rivers and thinking of the floor plan and the way that it was really like a forest. So again, nature culture.

André’s brief was it’s a Bentley, covered in honey. And then we added, okay, and the Bentley morphs into some secret garden.

SA: Yeah.

RS: Because that tree in the middle and all those shapes in that very geometric-austere building, that combination, that tension, I think was very strong. I think that was very unexpected. When people got up there, they were like, “Are we in this magical tree house? Are we in this natural, dreamy, just caramel world over New York City?” Even us picking that beautiful, shiny alder and sensual white leather, just really fun.

There was a profile of you guys in the FT that called you the “luxury’s default designers of atmosphere”. I was wondering if you could define what the Roman and Williams atmosphere is.

SA: Yeah, I liked that. I though that was a a nice title.

RS: I loved it.

SA: I was like, wow, that’s cool. Atmosphere-

Robin Standefer:

Just the idea of layers of atmosphere. I think that, again, comes from the senses, right? We’ve always loved what a place smelled like, what it sounded like. It was never just this inanimate design. I always tell the story of the Rizzoli book, and Charles Myers, our publisher who’s amazing. We wanted to put pictures in that had the Boom Boom Room picture, was on New Year’s Eve, and had balloons, and half-naked girls, and all kinds of wild business. And he’s like, “Interior books don’t have these pictures.” And I was like, “But, they should. Because the spaces, it looks like everyone’s dead in every shelter magazine. Where are the people? Where’s the life?”

And even when Steve and I, whatever we’re making, we want it to be active and animate. I think that that’s a lot of what that article… I mean, we did an interview for it, but that is just about this sense of atmosphere. Which is somewhat unclassifiable, it’s not just about the sofa and the beautiful wall, and I don’t discount that, but when something really is remarkable, it’s when it is alive.

SA: I keep thinking of the word “haunting”, is a word that I keep coming back to. Haunting has connotations of a haunted house, right? But if you think about the word “haunting”, it’s funny, but I love to think of what is a haunting sandwich, for example, or a haunting cup of coffee? That cup of coffee is hauntingly good, or that sandwich is hauntingly delicious. It means that something about it just stayed with you. It was like you ate this sandwich and you were like, “Oh, my God. The bread, the cheese, the herbs in it, this is hauntingly good.” It was the love put into that.

So that word comes up to me for a room, of course. It’s haunting. A hauntingly beautiful experience of someone who’s hauntingly beautiful. I think it’s such a great word that has no connotations of spookiness when I use it. It just means it stays with you. I tell you, it’s no formula for being haunting. I actually think it’s taboo to want to be haunting, because it almost will curse you and you won’t be haunting if you try to be haunting.

But I think our goal is to have a haunting after-feeling for something that we do, whether it’s a party or-

RS: To get in your head. And that goes back to this idea about being unclassifiable. We’ve always never wanted to be able to have someone put their finger on something. And I think a powerful, haunting memory is about that. How did that space make you feel? I can’t even tell you, it just got into my blood. Stephen and I have a fascination with that.

People will sometimes stop us, having been to certain spaces, and say, “It just got to me.” They can’t even… It becomes a little indescribable. And that, I think, connects to this idea about the atmosphere. Something’s in the air that you can’t quite define-

SA: Yeah, and I tell you…

RS: … that moves you.

SA: For us, the big part of that is not just design, but like Robin said, it’s music, it’s also the service. When it works well for us, the places are managed well and the staff has really done well. André is really good at that with children. If you could ever go to the Chiltern Firehouse, the staffing, the back and forth, that conversation with people is always really great because he’s so interested in that relationship.

RS: But Maison Estelle, which you’ve been to, Dan, that has that. And even us, playing with this finally digging in, I mean, it’s fun to work in England because you have these incredible, historic buildings, and then you can layer things from so many different periods. And we love to master that mix, to not… You know what I mean? Just to be interested in collecting and making things, and that you can again, put your finger on when any of them are from.

You start with these homes, you have celebrity homes, then you could have rested on your laurels and just done that, but then you started to do big, very popular hotels. And then at some point, you decide you’re going to do Roman Williams Guild and launch into this whole other part of your business. Why do that? I mean, if you asked anybody, “Hey, I know what I’m going to do in New York in the 2010s. I’m going to open a restaurant and a retail location.” Someone might be like, “Are you crazy? Why would you?”

SA: I know. The death of retail.

“That’s one of the toughest businesses around? So, why? Why?”

RS: But, Dan, just think about what we’re talking about. We love André. We love Alex, Ben Stiller, Kate Hudson. And we’re generous people. We’re in service, right? You really are there to bring their dreams to life. Maybe we have a vision for how to do that, but you have to know your place in that. And we say that even with the success we had. We’re not arrogant about what that means. And at a certain point, we were like, “Okay, are we ever…”.

We had a lot of vision for collections of our own furniture, our own lighting. We had a vision for working artisanally with people and curating in a way that we had the vision and ownership on our own terms. And we really couldn’t do that. And we love the design practice. Roman Williams is so close to my heart. We still have the most incredible clients. We’re back doing a lot of residential now as well.

But the Guild allowed us, we said, “Okay, if not now, when?” When you take stock after a certain amount of years, we were getting, whatever, 15-year mark, and we were like, Okay, what is next?” And people would ask us that, you’re going to ask us that in a minute. Everybody asks that. And we were like, “Okay, a 1000-year building. We want to build things to last.” I’m not being facetious saying that. We care about those things deeply, but we thought, what means something in our souls? What do we need to do to know that we get to a certain point in our lives, and we did something that was really meaningful? And we thought, okay.

I guess I want to back up, because a lot of designers have collections of furniture. We did a beautiful collaboration with Waterworks, with Peter Sallick, that’s still a bestseller and we’re super proud of, and also was the start of the industrial fixture in the marketplace. A lot of different companies, you pick them, you know the names, came to us and wanted us to sign licensing deals. And we just thought, it’s still not our own terms.

SA: Yeah, we came close. We did some prototype work.

RS: So close, pen on the paper.

SA: We did prototypes with the group of people on a chair, and there’s 15 people in a room, critiquing a chair. And we’re like, “Oh, my God. This is just driving us crazy.” We could do it for the hotels, we could do it for our resident. But I don’t want to do this for an original chair. That has to, I have to say, come from my heart when there’s 15 people talking about it.

We came so close to signing on the dotted line with multiple companies, maybe three or four different companies, and at one point, we just put the pencil down, and even partners for a space, and we just said… We started hunting for a space in the city and just got some investment from some of the people we had worked with, some of the people that we liked and liked us. Put together not that much money and had to sign a big lease, a 15-year personal guarantee on a lease, which is pretty difficult to do.

RS: Terrifying.

SA: Terrifying, but we did.

RS: That’s the word.

SA: We actually love our landlord. Our landlord though, has also become a friend.

RS: He’s like a yes. We love our landlord.

SA: We like helping him with other spots in the neighborhood. He’s rented our new office to us. He’s rented our art gallery to us now. We’ve become pretty close to him, and even his children. [inaudible 00:51:40]-

RS: [inaudible 00:51:40], amazing.

SA: Yeah.

RS: That’s old school. It’s like, okay, this person really supports you, wants to support us to building our own little world. And we wanted a big space, because when people… Even Gwyneth, whose house we did, she was like, “Oh, my God. This space is so big.” But we just thought, you know what? Go big or go home. We want a restaurant in it. We make a lot of different kinds of furniture. Our concept of our collections is really about a family tree, so we have different lights, and it’s never one style. So, we needed a space that was big enough to be the home of all those things.

We wanted to be owners. Then you fail or succeed on your own terms, right? Because you fail for someone else, it’s always like, who told you to do what? There’s not the purity of-

SA: So I think, as a designer-

RS: … what do I want to make? Go ahead.

SA: As a designer, sometimes it’s difficult to walk through a hotel or a restaurant you’ve worked on and you see that the flowers are half dead, or you see plastic flowers in a vase where it’s supposed to be real flowers. Or you see the bar, at the bar there’s a bunch of plastic containers holding ice. You’re like, “Oh, my God. You can’t use plastic containers.” As a designer, you have no authority. Once you turn it over, the operators take over. They’re like, “Who are you?”

We have to walk to projects, even into the Standard or the Ace, where you’re walking in a year later, you’re saying, “Everything’s screwed up here.” They’re like, “Who are you?” You wouldn’t even know, the turnover for managers and things are so high at these places, they don’t even know you. To be honest, it’s very difficult to go through that as a designer. Home’s different. You don’t get invited to a home you worked on all the time, years and years, but people take better care of their homes too.

But, I think opening the restaurant and the store gave us the opportunity to have that ownership of walking through and continuing to fix and improve. And we just love that. We love that daily maintenance. It’s something we’ve been thinking a lot about with our projects, is how we can make sure that we have that ownership continue after the place opens up. How, as a designer, you could still have authority to get your projects to function properly, and be cared for properly. It’s hard.

And then at some point, you guys… I’m not sure how many years it’s been now, but you have the Guild Gallery.

SA: Yeah.

Which brings you into yet another world of the fine art gallery and that whole universe. I know you guys have done stuff with art fairs and…

SA: Our mini-Met.

Yeah, yeah. You’ve gone from the Met to having your own gallery, and…

SA: It’s small. It’s small, but it’s a good, cute practice gallery.

Was there something you felt wasn’t fitting into the Guild, to the store, and then you said this deserves its own space, and it grew up from there?

RS: Yeah, during the pandemic… We’ve always had… I mean, this connects back to the Met… this fascination with clay and ceramics. We loved this sense of ceramics being utilitarian, the earliest ceramics, right? Clay is the most ancient, fundamental material, and ceramics are the earliest part of all our humanity. There was just something always very powerful and moving about that. Most of the objects that were in the British galleries were ceramic, and so that connected us even to, besides making our own collection, representing all these artists at the Guild.

And then some of them were working at scale and started to work at a bigger scale. And it was clear, even as Stephen said, “Our gallery is little.”, but there was no way to put pieces of this scale in the Guild. And you couldn’t really, I mean, the Guild is this eclectic crush. It’s almost Hearstian, right? And we loved that about it. But there’s some things that need serenity and singularity. Even as we were doing the Met, there’s some things where it’s like the [inaudible 00:55:56], is in big massing, and then there’s other pieces that have a lot more airspace around them.

That syncopation, like in music, is very important. The Guild Gallery was part of that. It’s like the syncopation of Canal Street. You’re in the intensity of the Guild where you’re buying dishes and glassware and a sofa and eating a chicken, and then you travel down the street to a very calm, serene, focused environment to look at a large ceramic chair. It was about that changing your perspective and perception of how you see something. We wanted to play with that and to do that and to also give these artists another platform.

When it comes to ground-up architecture, you’ve got since 2009, and I think… Tell me a little bit about 211 Elizabeth Street. Tell me about this project, and how it’s…

SA: Yeah. I mean, that’s an exciting part of our office we’ve done. I think it’s four ground-up buildings that we designed. I think we might be doing our fifth right now. They come every…

SA: … our fifth right now. They come every couple of years and we’re so grateful for the opportunity. But that was the first one, 211 Elizabeth. We’re trying to pick the roots of it, and I think it might come from the standard. The standard had a developer group. Dan Neidich is the developer on it, Dune Capital. And Dan and his team were at every design meeting, standing, sitting at the table, just watching, making sure everybody was following the schedule.

And a lot of people don’t know this, but on the standard, besides the interiors, we designed the exterior of the whole ground floor, all the brick buildings on the ground floor where the restaurant is and the beer garden. There’s a series of one-story, brick buildings with cornices and proper steel windows; looks very meatpacking district. I think when the scaffolding came down and the hotel opened, people just thought they were old buildings that had been renovated, but in fact, they’re brand-new brick buildings.

And again, just back to my architecture background, I’m pretty skilled with brick and how to do a traditional brick building. I could draw it in my sleep, and Dan and his team saw that. After the standard, I think it was maybe during, but they bought up a lot in 211 Elizabeth, and they came to our office and said, “Would you like to do a ground-up condominium project?” And we were, “Sure.” Again, I did some really fast presentation drawings overnight or something over the weekend and blew them away at these big, full renderings. And brick by brick, we put it all together. We did beautiful interiors with Peter Manning, who was the partner on the project. Peter was so supportive and just loved our personal style. So, it was really a blessing, that was.

And what is your creative process like today? Who’s doing what? When you’ve got something on the boards, what is that?

RS: Well, it’s really it depends on the what and what part of it. I think that the architecture in terms of the buildings, Stephen has powerful ownership of that. Although we then sometimes collaborate. I can be a muse for him; he can be one for me. Do you know what I mean? And I will concept an interior, but sometimes say, “Push yourself about the material to use. Like Fitzroy, let’s use all terracotta.” And then he sat down and drew literally a whole giant suite, which is a collection of moldings that were original for that building. And together, we found a way to get them made, although a terracotta building hadn’t been made in New York City for many decades.

So, in that case, I work for him, supporting the research of the materiality, and he’s drawing. On an interior, he’ll help draw for me. Like when we started on the new age, and he drew these screens for me, and we fell in love. So, it really depends.

SA: Funny, you can see that creative. Robin’s doing it right now because she’s really good at describing things. And I could do a beautiful drawing, say, of 211 Elizabeth Street. Stay up all night and do these, say, two renderings. They go up on the wall. Say, I had to give the presentation. What I’m going to do is I’m going to walk up and say, “Have a look. These are my drawings. I hope you like them. I like them. I hope you do.” That’s pretty much the end of the presentation. And I just expect them to speak for themselves. And sadly, sometimes they do, but most often, they don’t.

And Robin will describe the drawings. The drawing’s right there, but she’ll describe it. She’ll just begin the storytelling moment of, what do we have here? Let’s look at this together, and then take everybody on this one or two-hour journey. And the people are just melted, like puddles of love puddles by the end of the thing. And she just has such a way with words, and she’ll do it with me even before I do the drawings too, to get me charged up and optimistic and energized. She’s really good at that and a great coach. She’s got an amazing coaching ability. It’s like a Bill Belichick, like run faster. If it’s muddy, raining, you sprained ankle, just keep running, take you all the way. She’s just really good at that and-

Can you remember a time where maybe you do a presentation, and you totally bomb, and Robin comes in with an explanation that clicks with people?

SA: Oh, yeah. I don’t know. It happens very rarely, but there’s one or two times where she was busy, and I had to give it a shot. It just does not go very well. Or I don’t know, where you were not feeling well, and I did a couple. People just, they become legendary, like laughing things. Like Stephen just said, “I hope you like it” and sat back down. But it works really well together. But besides that presentation thing, Robin’s ability to put together objects and research and weave things like an editorial eye is unmatched to this day. I mean even just arranging 15 objects on the table, it’ll be a magical quality to it.

That’s a small example of it, but that leads to buildings and massing and choreography of a garden, of a room, of architecture. She’s really got a great vision from small scale to a big scale that’s pretty astounding.

And Robin, if you could tell me a little bit about the new lighting collection that you guys are working on. It’s called a certain slant of light. Is that correct?

RS: Well, that’s actually, I don’t want to correct you, but that’s going to be, and you’re going to come, Dan, it’s in November. That’s going to be a happening. I mean lighting for us, we love making lighting. So, to Stephen’s point, lighting is a perfect collaboration of what both of us are talking about. I love the atmosphere in some form. Stephen is so technical in his ability for just this sacred, perfect geometry, and lights need all that attention.

To make a really special light is a very complicated and difficult thing to do because it really is industrial design. So, we’ve always loved making light because, again, that creates layers of atmosphere. One of the first things we do when we come home is turn on every light, which is like a hundred, and that takes long time. And so, at the Guild, again, with the smell of the chicken and coffee and the whole collection, it’s an immersive experience. But we thought, with the gallery, let’s take the lights outside of that environment.

And Stephen and I happened to find this incredible space in Tribeca, and we’re going to take it over and put a hundred lights in it. And that’s going to be, part of it is launching a few new collections. And one, I didn’t talk about this because Stephen really, when he talks about this, he is very master builder. Every prototype of every object we create, he makes. And that’s something also now that is very old world and very incredibly unusual. That skill set is so, so rare in this 21st century.

And so, we started to play with a lot of these things during the pandemic because we were locked in Montauk and a lot of those lines, these cast glass sconces and this cast glass collection, a beautiful collection of seeds we call them, which are this blown glass with fluting and these beautiful forms. And so, those will be the new lights, another sconce that’s almost in a sense a machine age meets early deco. That cusp, you know what I mean, where it’s pre-industrial. So, it’s about something beautiful, but mechanical. Something that feels like jewelry or an incredible microscope or parts of a beautiful boat, but not quite that masculine where that masculine and feminine come together, like plant forms meet pieces of industrial design.

And so, we’ve been experimenting with some of those things and so this is going to be… A certain Slant of Light is an Emily Dickinson poem. And what that is about is, because it’s right around Stephen’s birthday… Stephen and I are opposite ends of the Zodiac; I’m May and he’s November. So, November is when the clocks change. And we know what-

SA: Almost to the date, right?

RS: Right.

SA: Yeah, I’m first freeze, she’s last freeze. But also, my birthday is the Doomsday when the time changes. All of a sudden, it’s dark at three o’clock. So, this is an idea to take that time and maybe do something extraordinary at that dark time, which will also be election time. Well, who knows what’s going to happen, but we’re just trying to bring some light to that time of the year and just do something brilliant, illuminating. We try not to fall into cliches with lighting, but we just want to bring, brighten up that time of the year with this big exposition.

RS: And start at 4:30 because it’s hard to imagine right now. Right, Dan? Look outside, that at 4:30 on the 14th of November, it’s dark. And a certain Slant of Light, again, is a beautiful Emily Dickinson poem about that, that slant of light, which is evocative. It’s sad, because all of a sudden, she was from the northeast, and the light is falling and darkening at an earlier hour. And so, we’re trying to extend that light a little with these hundred lights and figuring out also how to make it a happening.

Just talking about getting a little insider about the design world, first of all, when you go to Salone or even fashion shows, there’s off-site events. And New York doesn’t have a lot of off-site events, and everybody loves to go to those off-site events. And I thought, Steven and I thought, this is an incredible space, very classical space that is really mysterious. When you go in there, you are not going to… You don’t know what is coming in Tribeca. It’s not industrial. It’s really elegant, almost Beaux-Arts, European, Parisian.

And putting all our lights, which are a combination of families and a combination of styles and maybe… We’re playing with the idea of this huge bench where you could lay down and just look up at all of them. And so, we’ve really haven’t done something like this before and we like experimenting and allowing-

SA: Business-wise, it’s a risk, but it’s all basically the year’s inventory being used and hung. So, all has to be very carefully installed because it’s all for sale. It’s all going to go back in boxes and it’s basically our inventory. So, rather than sit in the warehouse protected, we’re going to just use them for this exposition, which is… That’s, again, our experimental business mode. As designers, were moving into other areas of operation. How lonely are those lights in those boxes? Let’s use them. Let’s just be careful we don’t dent them and-

RS: Or lose screws, yeah.

SA: Lose screws, supervise it.

RS: But even just our theatrical background, we love to do film and even some theater. And so, this is something a little theatrical, playing with how the light rises and falls, allowing people to really focus and have this intense massing of all these lights. So, for us, just is something experimental about that and we’re constantly, that’s our mode of innovating.

And what do you see beyond that? How do you see the firm going in your own? You guys have done so much, and it seems like you like to experiment with new things which, of course, is incredible. And no missteps yet. So, where do you guys, I’ll ask you a little bit of a job interview question, where do you see yourself in 10 years?

RS: I always ask that question. I tell you, people struggle with that answer. So, I don’t know. Stephen? I just think it’s like I’m-

SA: We have multiple irons in the fire. Is that what you say? I mean I’d love to continue the slow growth of a building every couple of years in the office. I just love that, the five-year projects that take five years or so, maybe six sometimes. I just build. It’s a couple more buildings. It’s so important to myself and even to a certain culture in our office of good architects. And that’s one thing for sure. We’re probably moving a little bit away from one-off restaurants that we’re not involved in the operations on because they’re fun, they’re exciting, they’re trendy, it’s part of a contest of new ideas, but they’re also just, I don’t know, they’re a pain in the butt sometimes. And I think we’re slowly stepping away from that realm.

RS: Unless we own it. So, we like more ownership and also just more building. There’ll be more tables. It’s things now, I say this with, so humbly, things that excite us. So, as long as we can pay the rent and keep this going, we just want to keep doing things that are inspiring. We rarely get bored because we don’t let ourselves. We’re in Montauk a lot. Our laboratory’s here. We’re here now, and just the experimenting of that, experimenting with the gardens. We’re really into, in this time in our lives, a lot of planting and gardening, and it’s having just a very powerful impact on the things we make. And that synergy together is meaningful, and I hope that that’s got another strong decade ahead of us because it’s pretty satisfying.

SA: We have three acres of wildflower native gardens. It’s a lot of management, a lot of weeding. We’re really involved in every inch of it, and it’s just a big part of our lives. Right now, it’s crazy too. It’s just going off. It’s blowing up, the garden flowers.

RS: You’re not that far away, Dan. You have to come.

That’s true. No one’s ever told me weeding was in their future, but I guess that’s-

SA: I love it. Well, it’s about native… It’s interesting because our gardens, after 10 years now, this meadow building, the diversity is just incredible. And in a funny way, we’ve actually learned to control it less, but there’s certain invasive vines that are really cruel to the other plants and just choke things out that we’re police a little bit, but letting the natural seeds that are landing in the yard grow or just random things. We’re like a little bit Darwinian, like naturalists, walking around, discovering new plants in our garden every day.

Thank you to my guests, Robin and Stephen, as well as to Sarah Natkins for making this episode happen. The editor of The Grand Tourist is Stan Hall. To keep this going, don’t forget to visit our website and sign up for our newsletter, The Grand Tourist Curator at thegrandtourist.net, and follow me on Instagram @danrubinstein. And don’t forget to follow The Grand Tourist on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you like to listen, and leave us a rating or comment. Every little bit helps. Til next time!

(END OF TRANSCRIPT)

The newest gallery openings this week, including the dark side of the American dream, traditions of Aboriginal Australian painting, a cheeky photographer, and more.

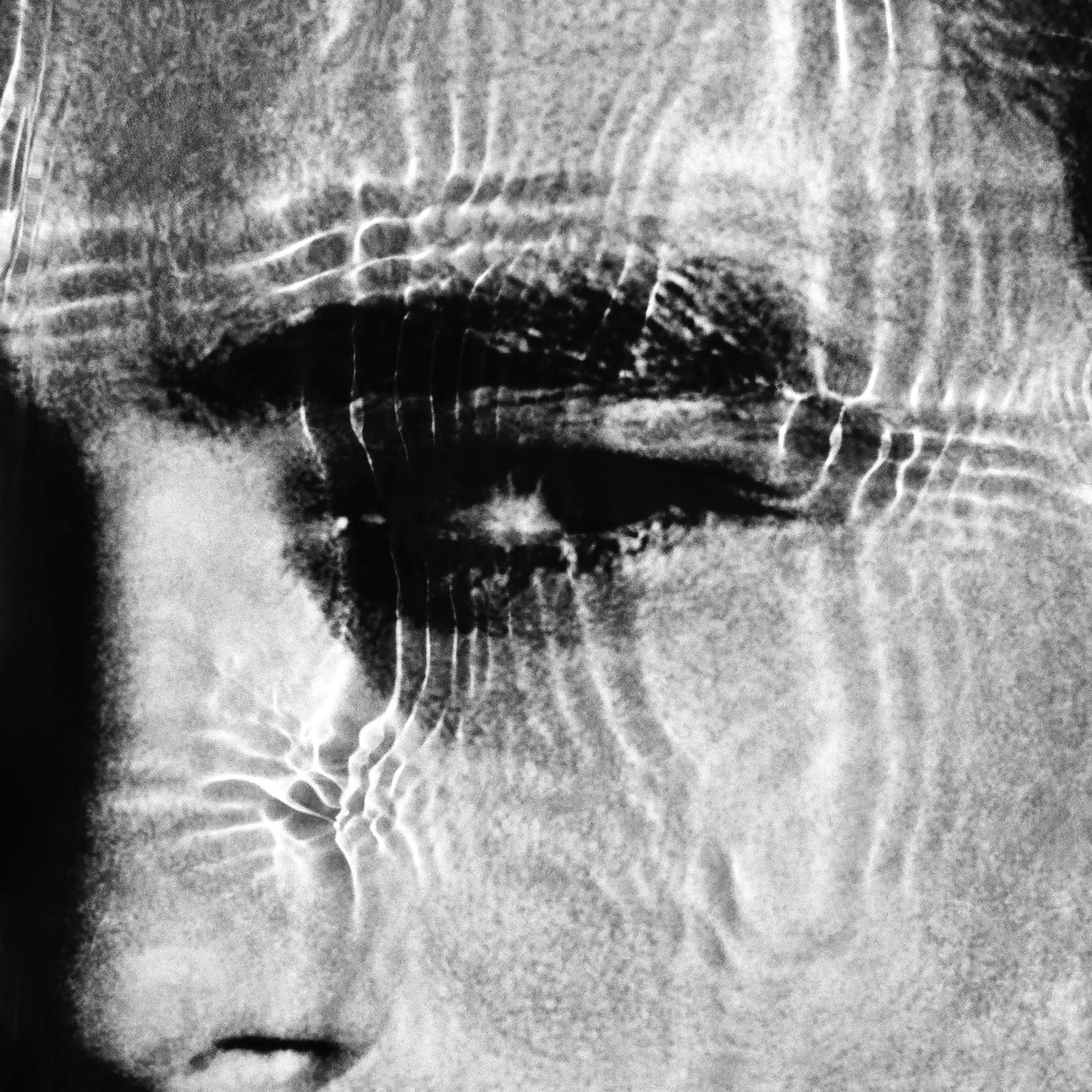

For Italian fashion photographer Alessio Boni, New York was a gateway to his American dream, which altered his life forever. In a series of highly personal works, made with his own unique process, he explores an apocalyptic clash of cultures.

Plus, an exciting young British artist receives a retrospective, Marcel Dzama's whimsical drawings take a political turn in L.A., and more gallery openings.