Annie Leibovitz Shares Her Vision in Monaco

The newest gallery openings this week, including the dark side of the American dream, traditions of Aboriginal Australian painting, a cheeky photographer, and more.

One of the most influential editors of her generation, Linda Wells transformed how we view the world of beauty and wellness. After decades at Allure magazine as its founding editor, she went on to launch a new label at Revlon, and she is now the editor of Air Mail Look, a beauty spin-off from the popular newsletter start-up from Graydon Carter. On this episode, Dan speaks with the enterprising journalist on her days as an assistant at Vogue, how she faced criticism and mansplaining when launching Allure, her thoughts about Ozempic, and much more.

TRANSCRIPT

Linda Wells: Beauty has always been a word that I find difficult. There was a reason that Allure was called Allure and not beauty, fill in the blank because I felt like it was exclusionary. People felt as if they had to meet a certain beauty standard to be invited into that party, and that was definitely the case then. Beauty was a very strictly defined, very limited symmetry and look.

Dan Rubinstein: Hi, I’m Dan Rubinstein, and this is The Grand Tourist. I’ve been a design journalist for more than 20 years, and this is my personalized guided tour to the worlds of fashion, art, architecture, food, and travel. All the elements of a well-lived life. When thinking of style and glamour, of course, you first think about fashion, hemlines, the new look and all that. But just as interesting to me and certainly as important is the world of beauty, a consequential element of human civilization since the dawn of time. And like so many aspects of 21st century life, beauty is evolving at breakneck speed. My guest today is probably the foremost expert in the field. The gargantuan industries behind it all, and its constant pace of evolution. Editor, journalist and innovator, Linda Wells. To many of you, you know her as the founding editor of the Condé Nast magazine Allure, the title was a first of its kind.

Taking beauty seriously as a topic worthy of constant focus, but had something of a legendarily rough start. More on that later. Wells began her career in the offices of Vogue before becoming an editor and reporter at The New York Times style desk covering beauty and food. After leaving Allure, following a nearly 25-year stint as editor-in-chief, she worked in the corporate world launching a new brand at Revlon called Flesh, and recently returned to the world of editorial at Air Mail, the famed newsletter/digital magazine created by former Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter.

And last summer launched Air Mail Look a beauty-focused spinoff. Full disclosure, I write for Air Mail on occasion. I caught up with Linda from her home in New York to recount her Devil Wears Prada–like days as an assistant, how she got the call to start a now historic magazine, how she overcame an endless stream of mansplaining from industry executives, what she thinks about Ozempic, her SPF of choice, and more.

(MUSICAL BREAK)

In all of my readings on your background, I tried to look as far as I could and I couldn’t find anything about your really early life. So I was wondering if you could tell me a little bit about where you grew up. Are you from Connecticut originally?

Well, I was born in New York City proudly, and then we moved around to various suburbs around New York, and Connecticut was where I lived the longest. And I was in Greenwich for about seven years, Darien for a year. And then when I was 14 we moved to St. Louis. So I like to claim that I’m a Midwesterner, but it’s really just me trying to be exotic.

And did you have any passions as a young person? What did you love to do on the weekends? It’s like, maybe a teenage Linda Wells.

Oh, teenage. Well, let’s going to go there. Drive around, smoke cigarettes, [inaudible 00:03:13] parties, that was my thing. But no, I love to read like every editor. I was a reader and I loved to write and I thought I was going to be a novelist, and I liked to paint and draw. So it was all arts.

You studied English at Trinity College, is that right?

Yeah, I did.

And why Trinity? And I guess—

Because I couldn’t get in anywhere else.

Do you remember where—

Does anybody go to Trinity? Because I can’t get anywhere else.

Oh, that’s—

I don’t know. And you know what, it was good for me. It was good that I didn’t get anywhere else because I sort of felt like I’m going to make sure that this is the best education I can get. So I became much more of an advocate for my own education, finding the best professors and spending real time with them and being a TA. So, it really was a good thing for me. And I was coming from the Midwest. It was good for me to go to a small school because I felt like I wanted to have that intimacy and sort of manageability of a school. And then I also felt like I wasn’t so wedded to the school that I went to Dartmouth for a term and I went to France for a term. So I didn’t feel this kind of lockdown. I have to take every minute of this institution. I was really free to wander, which I liked.

That’s incredible. And so, you graduate and what did a 21-year-old Linda Wells dream about doing pre-Vogue, which I think was one of your early jobs, but not the first.

Yeah, that was the first job. I dreamed about being employed. I mean, honestly, what I really wanted to do was keep going to school forever and ever. And my father was having none of that. He was like, “Listen, you’ve done English and art for your entire college experience. Let’s get serious.” And I was the only one in my family who was sort of more of a humanities person. Everybody else was much more finance and STEM driven. So I really had no idea what I was going to do, and just tried to find employment and got kicked around a lot as one does when they start to try to find employment in New York. Then I was hired at Condé Nast and that was my first job, and I had to take the typing test. We had to learn to type back then, and I had to take the typing test and I failed it seven times in a row.

How did you get the job and how does that relate to the failing the test seven times?

I know. Well, I took a secretarial course for a weekend just so I could learn to type, and then I don’t know how I got the job. I mean, I just think Condé Nast was really good at hiring assistants and in my career have had some of the most talented people as assistants and they’ve gone on to do extraordinary things. The HR department really could see sort of somebody who had the makings of something. I don’t know what. And probably it also had to do with being paid very little and not expecting to be paid anything at all. So, it was a little bit of that. They had this program where it was called Rover, which sounds so diminutive.

I was an assistant at Condé, I’ll admit.

Oh, God.

So I know exactly what—

The Rover Program.

The Rover program was like the elite A-Team job everyone wanted to have that. It sounded so amazing and to people that just sort of had a job. Everyone wanted to be a Rover because the people you get to… Being a Rover basically meant, you could sample, you would work a couple of months here or a month there, a week over there and you would just get to see all of the different titles and it was amazing. So you were a Rover?

I was a Rover no less.

Oh, wow.

It does sound not very honored, but it was great in the sense that it is really a good thing if you don’t have any earthly idea what you want to do or what you’re good at, because I could check neither of those boxes. And so I went around to different magazines and went to Glamour and went to… But I remember once I ended up in Circulation, they made me do charts. I was like, “Oh my God.” And the head of Circulation came out to me afterwards. He goes, “You know what, I don’t think you should ever work in Circulation.” And I was like, “Thank you. I don’t intend to.”

That’s good.

So then I had a stint at Vogue and was assisting the managing editor. Her assistant was sick for a while so I had an extended stint there, which was really great. And she became such helper and a mentor and a wonderful person. So when there was an opening at Vogue, she reached out and I got a job in the beauty department, which I never thought I would have any interest in doing, but I thought, “Listen, it’s a job. I’ll take it.” Little did I know that that would become my calling.

Yeah, what was that job like when you were at the beauty department?

Most junior level of anything. I mean, it was a lot of Xeroxing things and fixing the copying machine and getting people food and coffee, and it’s a lot of waitstaff stuff. But what was really great about it was I worked for an editor who was a real hands-on editor. And as I was carrying her copy from one person to the next, I would look and see what she’d done or I’d have to retype her stuff and it taught me how to edit. And I’d never known that before. It’s not really something that you are taught anywhere except on the job. So by watching her do it, I got to learn to do it. And so that was an extraordinary experience.

And then a lot of what was happening in the department was everybody fought a lot at the senior level. They were always bickering over who got to do what and who got what assignment and who got what attention, who was invited where. And they were all fighting. And as a result, the work would trickle down to the assistants. And so I was always like, “I’ll do it.” I always holding up my hand and asking to do anything. So it allowed me to write immediately and write no matter what little things, whatever it took. And people were glad to just dump it on me, and I was glad to be dumped upon.

Right. Did you get paid extra for the writing?

I got paid overtime, and so I made double my salary in overtime.

I got both overtime, but also if you wrote a piece, it would pay you like a per word rate.

Oh, I bet that was a good per word.

It was decent, I think. I don’t remember exactly what it was, but it was a huge amount of money for a little assistant like me. Yeah, I remember definitely jumping in front of the bus to do anything just because overtime and writing was basically the only way to make the job work financially also. It was like, that was how you made it work.

Yeah. I mean, it was just a thrill to have your byline.

Absolutely.

And then magazine, it was a dream come true. And at Vogue at the time, I don’t know if it’s still the [inaudible 00:10:25] case, but they wouldn’t put your name on the masthead unless you’d been there for two years. I mean, it was really an apprenticeship and—

Oh, no.

… you had to earn it. So it was great training. And of course, I found out later that Joan Didion was writing captions. I thought, “You know what, it worked for her.”

Yeah. I mean, you told New York Magazine at some point that there were certain editors whose mission was to make you cry. And I’m saying looking back on those days, I mean, today it seems like a totally another era in terms of what’s acceptable and the culture.

Yeah. You couldn’t do this.

I’m sure it still happens somewhere, but it’s not okay anymore. What is your sort of best and worst memory from those times?

I’m not sure if this is a best memory or worst memory, but one of the things that was striking about the job was that you had to assume you were the Vogue reader. So even though I was making a little less than $11,000 a year, I became in my writing like a snob. I had to become the most discerning to the point of being offensive. And so it was hilarious because you had to put on those clothes as if you were that person and the arrogance that went along with it. I think that one of the things that happened to me was that because everybody was always arguing and everyone was sort of doing their own internal strife and then they were racing out to try to curry favor with, who knows who, that some things would just tumble in my lap.

And one of those things was the man who created Crème de la Mer, this guy named Max Huber, who’s a person who’s surrounded with so much mystery that people have written stories about whether he was really a person or whether he was a myth. And he showed up at Vogue with an appointment and nobody could see him. And so I was told, “You go talk to him.” So I ended up having this meeting with this man who created this cream, and he was really eccentric to put it mildly. He took the cream, he put it in his eye to demonstrate how pure it was, which is not really a demonstration of purity, but go for it guy.

And then he ate it. And that was more proof of how pure it was, which just, again, it was a circus. But what was so funny about it was, of course, this cream goes on to become this revered. It was a one product brand, and then Estée Lauder bought it. And even people later, as recently as five years ago would come up to me and say, “Well, what was Max Huber like?” And I think I had to do a video for Estée Lauder about what he was like because nobody had met him.

Wow.

And I was just a kid sitting in the waiting area at Vogue listening to his spiel and it was hilarious. So, that was kind of funny.

And at a certain point you became the beauty reporter or one of the beauty reporters at The New York Times, and was there a culture shock of going from-

Oh yeah,

… Condé Nast and everyone in heels to-

Oh, God. Yes.

… the newsroom floor or maybe you… I don’t know who the desk next to you was, but it roughly could have been someone doing sports.

Yeah, it was so crazy. I mean, even when I was waiting to do an interview and I went through this whole interview process where I interviewed with the managing editor of the paper and Abe Rosenthal, who was the head of the newspaper. And at the time he had me into his office, and then I went into his little anteroom which was all Japanese, and we had to take our shoes off and it was right out of Mad Men. Remember that character at the ad agency played by Robert Morse who was walking around in his socks with the Japanese room. That was Abe Rosenthal’s room. Anyway, while I was waiting to do this interview and waiting in the reception area, people were stomping in and out and in and out. They were wearing combat boots and flak jackets and I’m like, “Oh my gosh, I’m going to have to get a new wardrobe.”

Of course, as superficial as I am, that’s the first thing that came to my mind. I had to get new clothes. And then when I started working there, yeah, it was a joke and I was on the newsroom floor. And one of my pals who sat next to me, you become friends with these people, we were all really young, and he was covering the crack beat when crack was new, and it was a new phenomenon. So he was assigned to crack and he got death threats and he was taken away and hidden for a while while this was going on. And meanwhile, I was opening flowers from the people I was reporting on. The first time you-

Oh my gosh.

So I was not exactly a hard hitting reporter, but I was surrounded with them, which felt really good. It was exciting, I feel like it was just such a great place to be. It was so full of life and personalities and feistiness and serious people. And I wasn’t used to being around really serious people who were doing things that were really important. And on election night, it was so brimming with activity and I loved it, and I was just the lightweight kind of joke, but it was so much fun to be around them and in that atmosphere. And I also think it made me a different kind of beauty writer. There were no other beauty writers. I wasn’t hired to be a beauty writer. I was hired to be a general style reporter, but even it was before the style section existed.

And so they didn’t really know what to do with me. And I kept pitching stories and they kept rejecting them, and I kept pitching and rejecting, and it took a really long time for me to get what worked for them. And I think it took them a while to get what I could do. And in the meantime, I was sort of learning how to turn beauty writing into some… Add some journalism to beauty writing, which did not exist before that. So that was a really amazing moment. I had to survive there. I was on trial for three months before they hired me formally, and the months were passing and they count your bylines.

You’re really assessed by how many bylines you have, and I couldn’t get any of my stories approved. So I had a story ideas approved so I kept, I’d say, “Give me anything. I’ll write anything.” I covered the social, the evening parties, and went out in evening clothes and my reporter’s notebook and did that. I just did anything they would let me do. But in the meantime, I really did learn how to report something that hadn’t really been reported before.

And when that came to beauty, did that change the way you perceived beauty because the way you had to report it was to a totally different set of editors?

Absolutely. I mean, we were very friendly to advertisers and not critical about anything at Vogue. It was really one of those very old-fashioned at the time, this was then 1980 to ’85. We were like, “If you can’t say anything nice, don’t say anything at all.” That was the modus operandi. And so that was certainly not the times, MO. So I learned to be critical and learn to ask questions and to not take the things that these companies were saying at face value. And a lot of what they said was not to be trusted. And I think that consumers had a lot more faith in products than they do now. But there was, I think beginning to be a little bit more science involved and a little bit more skepticism, and so it required more journalism.

And then at some point, how does that period then get to the launch of Allure? And if you could tell me that story about how that happened. Because I think when Allure launched, you were 29? I mean, you were-

I was older than that.

You were, are you?

I was older.

Because that was reported in a piece. So I’m fact checking-

Oh, no.

… being a recording.

No, I was 31, but still-

Okay still, but 31 is remarkably young at that time or any time to launch a major Condé Nast title from a scratch.

It was such an opportunity. And by the way, I was so happy at The New York Times. I had no intention of ever leaving. And I also was the food editor of the magazine. So when I moved to the magazine, I got that job too and I was doing two things at once, and I was going to cooking school at night, and it was idyllic. I had the best expense. I was able to go to four star restaurants and take my friends. Besides, it just being an incredibly, I don’t know, just a really satisfying experience as a person, just you get to do these stories and they’re run and people read them. It’s really magical. But then I got a call from Alexander Liberman, who was the editorial director of Condé Nast. And he was really the mastermind behind everything creative at Condé Nast.

And he asked me if I would have lunch with him. And before that, Anna Wintour had been trying to hire me to go back to Vogue, and I just didn’t really want to do that since I’d already been there. I felt like that would be just a return to something. And I had so much freedom at the times, and I just love being at the time so much. Then I got this call from Alex who said he wanted to have lunch and I thought, that’s interesting. I didn’t want to, he wanted to go to [inaudible 00:20:11]. And I didn’t really want to go to this incredibly public place with someone from Condé Nast, this leading person from Condé Nast and just say, “Hey, everybody.” I thought that would just be so rude to my boss, who was Carrie Donovan, who was like a mother to me. I really loved her.

So I said, “Let’s meet and just have a meeting.” And so we met in his office at the Condé Nast building on Madison Avenue. And S.I. Newhouse walked in and I was like, “Oh, I guess they’ve got something else in mind.” And so they said that they wanted to start a beauty magazine and would I do it? And really, that was pretty much the conversation. I mean, there was no… “We have a name. We have done market research.” No, no. Condé Nast at the time did not do market research. They did not test things out. They knew that beauty was a very highly, a subject of high interest among the readers of Vogue and the readers of Glamour. And so they decided that because of that, there was both an audience for it. And of course it was advertising, and advertising was just brilliant.

So I said, let me think about it. Really, who’s kidding who? Of course, I was going to do it. But I wanted to understand a little bit too about what they envisioned this to be, because I felt like having done journalism, I didn’t want to just go back to writing editorialized versions of a press release.

So we had conversations about how to make this journalistic and what the risks would be, and are they willing to go there? And S.I. Newhouse was completely willing to go there, and it really caused a lot of edge among the other magazines at Condé Nast because they felt as if we were critical, the publishers in particular at the other magazines were going to get punished and everybody would suffer. And so it was not the friendliest beginning to… So anyway, obviously, I went to Condé Nast and I was 31, as I said, and started, and there was nothing. There wasn’t a single staff person, there wasn’t an idea, there wasn’t a name, nothing. And so I just started, sat at a computer and just started batting out ideas and concepts and hiring people. Once you hired enough people, you started to gather this whole thing together. And everyone came with ideas, and writers, and we had…

So we did a prototype, and the prototype was as you know, a magazine with no real articles in it, but it was treated as if it had real articles, but it was such an artificial experience. And Tina Brownie was, “Don’t do it. They’re going to want you to do it, don’t do it.” I was like, “You’re Tina Brown. You can tell them, no.” I am a child who has no experience whatsoever to do this, so I’m hardly going to be the person to say, “No, I’m not doing it.” So I did it, but the art director really took control of the whole thing and designed it in his office with the door locked and would lock the layouts in there. And there was no back and forth or communication. It was just, “That was it?” And Alex Liberman was also so flummoxed by the whole thing like, “Wait a second.” First of all, it was the first magazine that was designed on computer as opposed to cutting out and taping and gluing and doing a manual layout.

What year was that? I think it’s ’96?

’90.

Oh, ’90. Sorry. Excuse me.

We launched in ’91. And so it was ’90 when we were doing this.

’91.

So Alex, we’d stand there with these layouts and he’d try to peel up things, and they were not… You can’t remove pictures. And so it was so frustrating to him. And the whole thing was sort of like a runaway train. And the two of us were sort of standing there watching it go and not knowing how to stop it. And the art director had enormous more experience than I did. So we printed 40,000 copies of this prototype issue to give to advertisers and to whatever. And before it was distributed, S.I. Newhouse called me in his office and said, “We’re going to shred them all, and we’re going to start over-

Wow.

… because it’s not good.” And I was like, “Oh, jeez, that’s not good. That’s a bad start.”

That’s a very bad start.

It was terrible.

What was his criticism? What did he not like about it? Was it the layout or was it like a…

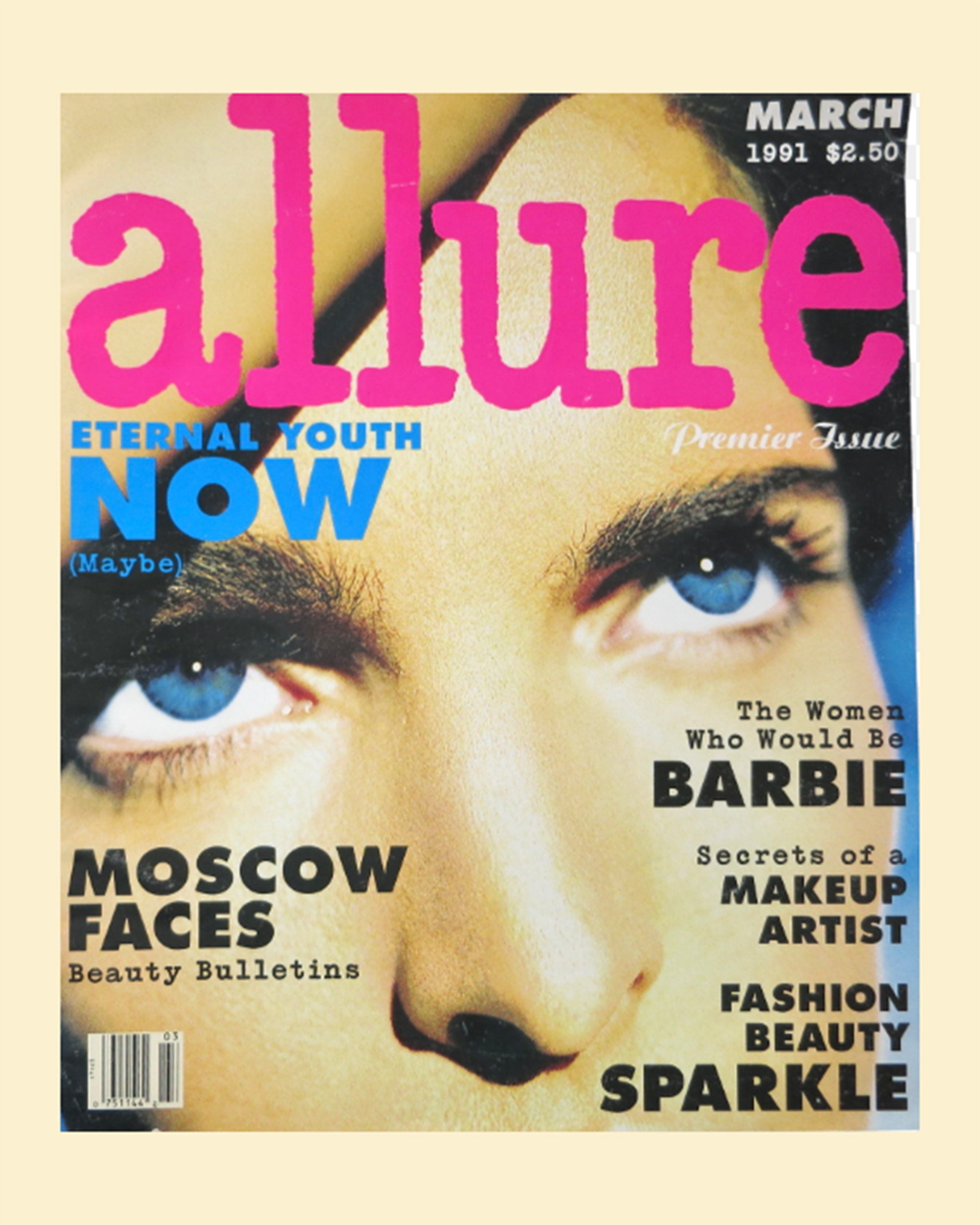

He did not like the visuals. He didn’t like the layouts. He didn’t like the typography. It felt aggressive, but not in a interesting way. It just wasn’t good. So off we did, new art director, new team, start all over, and we just started with a regular issue. And we started with a March issue and that was it, we were monthly after that. There was no test, no nothing, no wind up. And that was really actually much better in the end because if you have too much time, you’re going to make something that isn’t good. It’s much better to have very little time.

And that I felt more comfortable working under a tighter deadline. And we had a great art director, and Alex was really involved, Lieberman, and it was oversized. The issue was bigger than anything that was out there. And it was sort of cheaper paper deliberately. We wanted it to look sort of tabloidy and energetic. Because the subject was beauty, we wanted to counteract the expectation of that subject and not have it look like a magazine that you would find in a salon that was all about hairstyles. We wanted it to be newsy and aggressive and have a lot of voice and a lot of spirit. And so that was what we did. And when we launched, it was so wildly criticized. People said, this is the ugliest beauty magazine I’ve ever seen. And we’re like, “Yay. That was our intention. Go us.”

And that oversized, how long did the oversized and print element of it, paper quality element of that last? Because it eventually changed to a more traditional.

Yeah, it changed pretty quickly, and it was four months. And the reason, and everyone thought, “Oh, they did it because it was too expensive.” No, in fact, it was less expensive to use that cheaper paper and that larger size. But the crazy thing about it was we couldn’t fit in any of the newsstand slots. So it was like, “Oh, huh, a new magazine that you can’t put anywhere. That’s not a very good idea.” And then the advertisers had to change their ads in order to be in the magazine because it wasn’t just a proportionate resizing.

It was much more difficult back then if we’re talking about the dawn of digital publishing. Yeah.

Computer [inaudible 00:27:11], that’s right. So we were like, “Okay, great. We can’t get our newsstands and we can’t get advertising.” But otherwise it’s just terrific. So the July issue had seven pages of advertising, which PS is not a lot of advertising.

No. Especially, not at the time.

No, that’s not the time.

Today, you’d be dancing on the ceiling.

I know, it’s like you congratulate yourself today. But then that was a disaster. And it wasn’t just because the paper size, it was the people were really just completely baffled about what this magazine was and why it was it beauty, and the beauty industry that was very angry. I mean, I had heated conversations. I was lectured to by CEOs of various beauty companies.

Oh, gosh.

“You’ve made an ugly magazine. This is not what we expected. This is not reverential, da, da, da. And so we had a lot of battles. We had a lot of battles.

Do you feel that these executives who are, I’m just taking a guess, were all guys, were-

They were all men.

… talking down to you?

Oh, sure.

Mansplaining?

I mean, listen, it’s not the first time. It was certainly, and it didn’t bother me. I mean, I felt like, “Sure, you can say that, but I really believed in it.” And so, I was very happy. I mean, happy as an exaggeration. I was very willing to go to all these meetings and be yelled at, and sit there and listen and leave. But one of these executives, his wife finally said to him, “You idiot, this magazine is what all these young people are really excited about. You get right back in there.” So I thought, I love that woman. So yeah, so it was a rough couple of months, but then it sort of almost immediately just went soaring up, which was great.

Was there a moment that you remember where you feel like, “Okay, we’ve arrived.” This is—

Yeah. Yeah, I do. I think I went away for a weekend and I saw the magazine sitting on a chaise on the side of it at a resort by a pool. And I thought, “Ah, that’s it. It’s out in the world.”

It’s been read at the pool, which is I think the greatest…

Someone’s reading it, I don’t know them. And I kept thinking, “I should go and thank them.” And then I thought, “No, wait, maybe I’m now at the point where I don’t have to do that anymore.”

Was there a peak Allure in the way of your memory of it, in terms of the business and how it sort of evolved and your role there?

I don’t really think about that, but I think about peak moments. There were things like I was on the Oprah Show three times talking about-

Oh, wow.

… controversial issues attached to beauty. And it wasn’t just, you’re like, “Oh, here’s a before and after with makeup.” It was-

Serious. Yeah.

… very aggressive, yeah. And that was great. We got John Updike to write for us. That was amazing.

Oh, that’s great.

He’s not a beauty writer but we always would go to… It was one of the personal intelligences that I’d read a book I liked or a story I liked and be like, “Let’s see if they’ll write for us.” And we would get such great people to write for us, because they never really thought about beauty as a subject. But then once they started thinking about it was like, “Ah.” And so we tried John Updike a number of different times, and we’d send him pitches and we’d have to do it by mail, like snail mail. You’d send him a letter, typed, and send it, and then he would send back one of those postcards that you could buy at the post office that was like… And he would type on it, “Thank you but no.” And it was just like, every time he’d send it back would be a little bit humiliated.

And this wonderful editor I was working with Mary Turner, who had worked at The New Yorker before was really masterminding all this. And then I thought about how he’d written about his love of the son and how… Because he had psoriasis, he would spend all of his summers with the women whose husbands were at the office, and he’d be sunning and spending all that time in the beach. And so he wrote a story for us about that. We didn’t have a contract, we just got it in a manila envelope one day, and there it was John Updike.

Wow.

So it was those sorts of things. We had such great writers. Elizabeth Gilbert wrote the story that ended up becoming Eat, Pray, Love that she wrote about going to a yoga retreat in Bali. And when she was working at GQ at the time, and when proposed it to me and Susan Kittenplan, her editor, I was like, “Oh, that sounds like the most boring subject ever,” but it’s Elizabeth Gilbert. Of course, we’re going to do it. And so that was an amazing story. And Cheryl Strayed wrote about going out into the wilderness during that hike, and that was before Wild came out. So, we had these moments of just marrying literature with beauty, with perception, with journalism. It was really satisfying. And those were just sort of those little things that I was passionate about, but there were a lot of great moments.

Yeah, no, I know exactly how you feel. I mean, obviously you were there for 25 years.

25 years.

… and this is a very 30,000-foot question, but how do you see, now looking back, how did beauty evolve as a concept in the time that you were there?

You know what, we were so lucky our timing was so fortuitous because beauty was something that was, people didn’t talk about it, people were embarrassed about it, you didn’t tell people that you were… It was really synonymous with vanity. Everything that was shameful was beauty except for maybe fragrance. Fragrance was sort of evolved and lovely and poetic, but everything else was sort of embarrassing and either clinical or so fluffy and nonsensical that no one could take it seriously. And then just all these things happened, there were scientific developments. Retin-A was a drug that was approved to make skin look better. Botox eventually came around. Dermatology went from something that treated rashes and was clinical and boring to the sexiest thing you could be with a dermatologist, and go to the dermatologist. You treated your dermatologist like a hair salon. And so with all that, just the advances came one after the other.

After the other people became much more interested in beauty, people became less ashamed of it, and it came out of the closet as something to be discussed. I mean, even things like silicone breast implants, which were a controversy in the early days of Allure than we wrote stories about in the dangers of silicone breast implants. That was something that was talked about. Photo retouching. We wrote the first story about the fact that photos are retouched. A lot of things about perception and how, what we see the world as and how beauty is presented back to women and to the general population and culture. And the beauty myth came out, and that was that book about how women are sort of punished by having to pursue beauty, and that takes them away from… That was the theory, that takes them away from other achievements that are more meaningful. And so, that just became a topic of conversation and all that made beauty a really interesting vital subject for coverage.

And get to that. Did you ever have a moment where you got a product across your desk, wrote something where someone at one of those other titles, as you mentioned, where people got jealous or really… Did you have a stern talking to from anybody at some point to be like, “You’re really pissed off some person here and they don’t like it.”

Oh, sure. I had so many of those moments. They could-

How did you handle it?

… barely be called moments. I had a lot of support from S.I. Newhouse, and that helped a lot. But virtually every big cosmetics company complained, pulled out their advertising. The only exception was Estée Lauder. Leonard Lauder was an absolute hero and a supporter. And even when things annoyed him, he would tell me what he thought was wrong and everything, but he never acted with his advertising. But every other company, they would all cancel their advertising. And the way I handled was that sort of that first incident, I would go and either we’d have lunch, that was a very civilized way to do it, or I’d go to someone’s office and they’d yell at me. And one time it was someone from a huge cosmetic company and he decided that he was going to take me down and it wasn’t enough. Take down Allure, he’s going to take me down.

He even said, “I’m going to ruin your family.” I was like, “Oh, that’s interesting. This is very mafia of you.” And so he decided that he was going to have a meeting with me and the CEO, Steve Florio, and it was scheduled for December 24th at 04:00 or something like a Christmas Eve. Yay.

Wow.

That’s a terrific concept. And I had two very young children. One of them was still in diapers and had a trip planned with them and my husband, and we were all going to go down to the Caribbean and I couldn’t go because I had to be in this meeting. And my husband ended up taking my sister with him, but they were stuck in Puerto Rico, and they ran out baby formula and they ran out diapers, and it was just a drama. And then I was getting actually metaphorically murdered in this meeting, and this man was so angry.

And then he was shaking with ire and his face was red, and then he got it into a coughing fit, and he opened up his briefcase. And in it was just pills, solid pills. I was like, “Oh my gosh, this guy is not well.” I had so much sympathy for him after that. And then we talked it out and he calmed down a little bit. And then I walked into the elevator and he gave me a kiss and a hug, and he said, “Well, I’m retiring. On December 31st is my last day at the job.” I thought, “Oh, your last act, let’s take her down.” But it was bizarre and then nothing ever came of it. So I felt like whenever anybody was angry at the magazine, my job was to hear them and to understand what it was and take that in for whatever that meant. I never apologized, but it was really just, “Okay, let me hear your side of it.” And to me that’s like, “That’s what you have to do. You’re the boss. You’ve got to suck it up. Punch me.”

Wow. And you also spent a few years in corporate America on the other side of the fence at Revlon as a creative officer, and you launched their brand Flesh. I mean, as an editor with all this experience, what did you learn or what was like going to the other side essentially? It must’ve been quite the trip.

What I did not know was could fill volumes upon volumes. I mean, I really would sit in meetings and just Google acronyms because I didn’t know what anybody was talking about. It was like, I landed in different country.

What’s the acronym that sticks in your mind?

Oh gosh, you know what? I forgot all of them.

Okay.

And things like, even I was just thinking about the other day, they talk about the customer, and I so naively thought that the customer was the person buying the products. But no, the customer was Rite Aid, CBS, Target.

They’re the client, basically. Yeah.

Yeah. Yeah. And there was a great focus on that, and it’s such a great brand, and I really thought it would be such a fun experience to bring back that creativity and that excitement of the brand that it had, especially in the 1970s and ‘80s. And creatively, it was an extraordinary experience and I learned so much. But we did the big campaign with Ashley Graham and Adwoa Aboah and Imaan Hammam, and that was an exceptional experience. And I wrote a lot of the campaign and I would just roll up my sleeves and do whatever, and it was really adventurous. And then while I was there, the CEO at the time decided that it would be great to have a stronger relationship with Ulta. And that’s when he got the idea, “Let’s start our own prestige line following the map that indie brands had very quick to market, not a lot of red tape. Let’s just move quickly, make quick decisions.”

And that’s very different for a corporate entity to work that way. So, he gave me an enormous amount of freedom and support, and I worked with a makeup artist creating the brand, creating the products, creating all the colors. I named them. I worked with a tiny team. We created the logos and the packaging and everything. I think there were 106 SKUs, too many by the way. And we created them in 11 months from concept to getting on the shelf in Ulta.

Wow.

I was the one who went to Ulta and pitched it to them, and I’d never done that before. And I was halfway into the pitch and they were like, “We want it.” So it was such a fun experience. It did not last. The CEO left after a few months of the brand. I don’t even know if he was there when the brand was launched. I don’t think so. And so that was awkward. And then Revlon was busy dealing with other financial issues. So the brand just died, which was too bad but I still have a lot of the products, and it was a great experience. The products were amazing.

In this era of people doing the direct-to-consumer thing and launching something on Instagram and all of that stuff, did you ever get that bug where you were like, “I’m going to start my own, whatever.”

That would’ve been a good way to start. It was a different mission. Our mission was to get into Ulta and have better relationships with Ulta and Revlon. And so that meant that it was totally different. It wasn’t like, “Let’s launch a brand and have that brand grow slowly and make its way.” It’s a better way to launch a brand. It’s a very difficult to do it the way we did it and be successful because it’s just like the financial burden is huge, and supply chain and all the other things, distribution, it’s just a lot to deal with. In my dreams, it would’ve been great to start with a few products, DTC, the way that a lot of indie companies start. But having done it, I don’t know if I really want to do it again.

It was great. But I think the other piece of it is the beauty industry is so oversaturated. There are too many products, there are too many brands. And I have such admiration for all these new brands that come about but it’s like, I just think that future is going to be really tough for a lot of these brands because they don’t have a really strong point of difference. And there’s so much static. You really don’t have great success unless you’ve got a big name behind it in terms of a celebrity or an influencer, someone like Rihanna who did it with Kendo, which is owned by Sephora, which is owned by LVMH, that’s a genius way of going about doing something. But there are all these other influencers who have huge audiences and followers and believers who are really dedicated to what they do. And they’ve closed their businesses and their businesses have failed. We’re in a state now where there’s too much, and I don’t really see the point of adding to it right now.

I know. I can totally see that. Now, we get to sort of the Air Mail part of everything. And you started writing for Air Mail before launching this new, I guess, vertical might be the right way to describe it, an Air Mail Look. And tell me what is Air Mail Look?

So Air Mail Look is all about beauty and wellness, which is a wonderful broad topic. So when it comes out of the Air Mail universe, meaning it has the sort of DNA of Air Mail. And having written for Air Mail, I guess maybe for two years. I can’t even remember, I have so no sense of timing. But the stories, they got a lot of interest in regular, we call it big Air Mail Look, we call it the big Air Mail.

And I laid out a territory in a way in those stories, and it would be like makeup, skin, hair, which is the typical beauty stuff. And then sleep, sex, fitness, vitamins, all the longevity, all that other, the topic has gotten so wonderfully broad and varied. So then we launched Air Mail Look, which I think of as another digital magazine. It really focuses on those topics alone. And we’ve got a lot of beauty used to be a female-oriented subject. And now that we’re in this world of all genders and concepts, we also have a really strong male audience, and I’m sure everything in between.

I was going to ask you about that. How has that sort of evolved? I mean, because obviously when it comes to dermatology and the injectables and the whole world of… Men are a really growing and big part of this world. Is that something that floors you to this day or…

No, but the funny thing is, I remember when I was at The New York Times and that was like ’85 to ’90, and I wrote stories about men getting into the beauty world and skincare for men and makeup for men, and what was going to happen. And experts would say, “We’re on the edge of a male boom, a consumer boom among male customers.” And we were like, “Okay, that didn’t happen and it didn’t happen again.” And then the metrosexuals, it still didn’t happen. It’s never really been the moment. And I think that it’s been a little bit of a creep, but it’s not like this before and after where suddenly there are all these male consumers. But the things that most traditional male consumers are interested in are very much in our wheelhouse, which is longevity, biohacking, hair, hair loss, all the things. And I think skincare too, men are much more open to being into skincare.

There’s still makeup for men, but I think it’s not the boom that people expected it to be. We do travel and we travel to wellness clinics and spas. So it’s almost like even when you think about no self-respecting luxury hotel can exist without a very vital spa. You have to have a really good spa. And every great hotel that you’ve ever heard of usually has done a renovation in the last five years and instituted a fantastic spa, and it’s got some bell or whistle that’s different from other ones. So, it’s just this boom in this subject in a way that we didn’t expect.

You had spoken earlier about some of the major things that happened during your days at Vogue is that it was an exciting time that new things were coming on the market and the FDA was approving all of these new things.

Well, that was really Allure, but yeah.

Right. No, that’s what I mean during your time at Allure, but now that we’re in this new age of Air Mail. I’m wondering what is the major advance today in the year 2024 that you think is going to make a huge impact like it did back in the day?

Longevity.

Oh, okay.

There so much going on longevity. Okay, that’s one. The other thing is Ozempic, it’s a world changing culture changing drug, that class of drugs. We just know the beginning of it. And I know that everyone wrings their hands and thinks it’s horrible, and people shouldn’t be concerned about losing weight and being thin, but it’s hard to change that attitude just by will. We wanted to be bud positive and accept everybody, but we’ve had centuries upon centuries of valuing a different physical form. And so it’s hard to just sort of say, “Okay, we don’t believe that anymore.” So there’s that, and it opens up a lot of psychological things. And it could end up being a treatment if not a, I don’t know, even a potential cure to eating disorders. It could be something very profound, but it’s going to change our behavior, our longevity, our health, our ability to exercise late into life. I mean, we don’t even know. It might be a cure for alcoholism or treatment for alcoholism. It might be ways that we just can’t even anticipate. So I feel like that’s a world changer.

Are you skeptical for something that has been adopted so widely, so fast, and with such gusto where part of the… It’s not a drug, it’s a cure for a disease. You take it for two weeks and then stop. This is something that you’re meant to just take for a very long time. And so are you on the suspicious side of, “Hey, the millions and millions and millions of people are going to take this for their entire adult lives, possibly. And we don’t know what that will look like.”

Yeah. Yeah, yeah. No, I’m definitely, I’m very skeptical of anything. It’s always like, I’m always questioning it, but there are people who are taking it situationally too. And I wrote a story about that recently about how people who were very thin people, actors that you know and models that you know and fashion people that are taking this to fit into their clothes for the fill in the blank, the met ball, the fashion week in Paris or whatever it happens to be. So I think that we’ll see microdosing and situational use of it. But yeah, I mean, who knows?

I mean, I think that people are jumping in with both feet and it’s still uncertain long-term how something like this is going to fare. I’m always trying to lose 10 pounds, it’s just annoying and stupid. And the amount of energy and time and thought, it’s always in my head, [inaudible 00:51:29] only use [inaudible 00:51:29] that weight. And someone told me about being able to get it, and I was like, “Oh God, I really want to get it. I think how great that would be.” And then I just thought, I’m afraid, I’m just too afraid to do it.

Wow.

So personally, I am not doing it. I also think there’s a point where you just sort of say, “You know what? I accept myself for who I am,” except for those times I’m annoyed. And I can’t fit into the thing I want to wear. Well, obviously the editor in me is like, “You’ve got to do it and write about it.”

Yeah. Well, I don’t know.

I have another writer who’s been on it for a while, and I’ve talked to her about doing it, but she feels like there’s nothing to say. I feel like there are a thousand ways to slice and dice the Ozempic story because there are thousands of different angles to get on it. And it’s so interesting.

That’s the point. It’s your next book.

So that to me is a huge thing. Well, nobody want to read your book about that. But I think it’s a huge thing. And I think that we are just at the beginning of what this is going to be. And the controversies are interesting. And I also think that there’s a level of judgment and sort of shame attached to it. And I think that’s one of the things that I’ve always been really careful not to have in Allure and in my writing is, I don’t want to judge people for what they’re doing.

So we cover plastic surgery all in a way that people did not cover it. When I was at Allure, we had this fantastic writer, Joan Crow, who made it her beat. And it was never judgmental. It was never like, you’re a bad person for caring or you’re a bad person for getting it. Or it was a got you thing where you’d be like, “Oh, this person got surgery and we can tell.” I just don’t want to attach shame to any of these things, I want to report them. Because too often people have been ashamed of doing anything in the world of beauty.

They were ashamed. Women were ashamed and made to feel embarrassed and wrong by getting their hair colored once upon a time. And there wasn’t even a whole ad campaign, “Does she or doesn’t she?” Like it was this dark secret. When you have shame, you have people doing things that are dangerous and they’re hiding things. They’re lying to their doctors, they’re doing things without being smart consumers. And so, my feeling is this is not the place for shame. So we can leave that to somebody else to shake their finger and tsk-tsk, but it’s not going to be me.

This interview will come out in a few months so we’re doing this in advance. So are there any stories that you’re working on right now for Air Mail that you feel, you think are really fascinating, you’re looking forward to see how they turn out?

I’m always interested in how the story I’m writing is going to turn out before I write it. I’m hoping it will turn out. But I’m really interested in the whole way that science has infiltrated the beauty world and how people find science to be this hottest thing, sexiest thing ever. And the way that’s gotten into the skincare world. And every chemist, every dermatologist has a skincare line. Are they better? What are the claims, the claims that people tell me. I always have these people from companies saying, “This gets under the skin and it changes the dermis and the fibroblasts are strengthened and this adds collagen.” And I’m like, “But you can’t claim that. That’s our drug claims.” They’re like, “Oh, I know we can’t claim it.” I’m like, “Well, then why are you telling me this? Do you want me to claim it? Sorry, I’m not your mouthpiece.” But it’s really interesting to me the way people in the industry are trying to attach themselves to the medical and science community to give their products legitimacy. So that’s one thing I’m really interested in.

I’m working on a story about how sunscreen got sexy, and sunscreen was like the vitamin you didn’t want to take. And when I was growing up, it didn’t even exist in a very good way. And then you ignored it. And everything that was sexy about sunscreen was not the screen, it was the sun. And so it was Bain de Soleil and it was baby oil, and it was being outside, it was the scent and it was St. Tropez and it was all the fun stuff, and it wasn’t the protective stuff. So then sunscreen became very, very clinical and it’s treated as an over the counter drug by the FDA and everything. So it was super clinical and everyone felt they had to do it, but that’s not fun. And so now there are sunscreens that are fun and super group broke that by making it glow in and making it every day and making it sort of more like skincare.

And then there’s a newer brand called Vacation. they have a sunscreen that comes and it looks just like Reddi-wip. So it’s like that little foam that comes out. And then they’ve got one that looks like baby oil, and it’s in that package. And it’s exactly what you should not be doing is putting baby oil on your skin, but it’s a sunscreen. And then they have one that’s like Bain de Soleil that’s coming out I think in the spring. So, they’re taking all of those nostalgic concepts that were really all the bad behavior and adding something that’s good for you, but keeping the fun. So, that’s interesting to me.

What is your sort of SPF of choice?

Oh my God, 50 at least. I do go to wonderful, warm tropical places, and I love to swim and be outside and hike and paddleboard, and I’ve just covered up. And I wear like SPF clothing and beekeeper.

And what would you say, no matter how pedestrian, what is the greatest bit of beauty advice anyone has ever given you?

I mean, really it’s just stop looking in the mirror. I feel like what’s going on in the world of Gen Z is this complete… The phone and the videoing and the TikTok making, and it gives you an enormous preoccupation with the way you look. And when I was an adolescent in my early 20s, I wasn’t looking at myself. I would look at myself in the morning and then I would go out into the world and I wouldn’t look myself again unless I happened to be washing my hands in a bathroom mirror.

It wasn’t just not a constant issue, and I feel like being faced with. Even just being on a Zoom call, you were so much more self-conscious, but if you’re really posting pictures of yourself all the time, it just changes your relationship with the way that you appear. Dating apps, all of it is so much about appearance and it’s just like step away from that, from looking at yourself. It’s a big burden, and I think that’s why we’re seeing girls who are going to Sephora and getting skin care at the age of 13 and buying Drunk Elephant. And Drunk Elephant is a good brand, but not to slag them, but it’s more just this people thinking that they should be getting filler under their eyes for some reason, or having their buckle fat removed and it’s just like, “Stop it. Stop thinking about it. Stop looking at yourself all the time.” It’s a big burden to be faced with yourself all the time.

(MUSICAL BREAK)

Thank you to my guest, Linda Wells, as well as to everyone at Air Mail for making this episode happen. The editor of The Grand Tourist is Stan Hall. To keep this going, don’t forget to visit our website and sign up for our newsletter, The Grand Tourist Curator at thegrandtourist.net, and follow me on Instagram at @danrubinstein. And don’t forget to follow The Grand Tourist on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you like to listen and leave us a rating or comment. Every little bit helps. Til next time!

The newest gallery openings this week, including the dark side of the American dream, traditions of Aboriginal Australian painting, a cheeky photographer, and more.

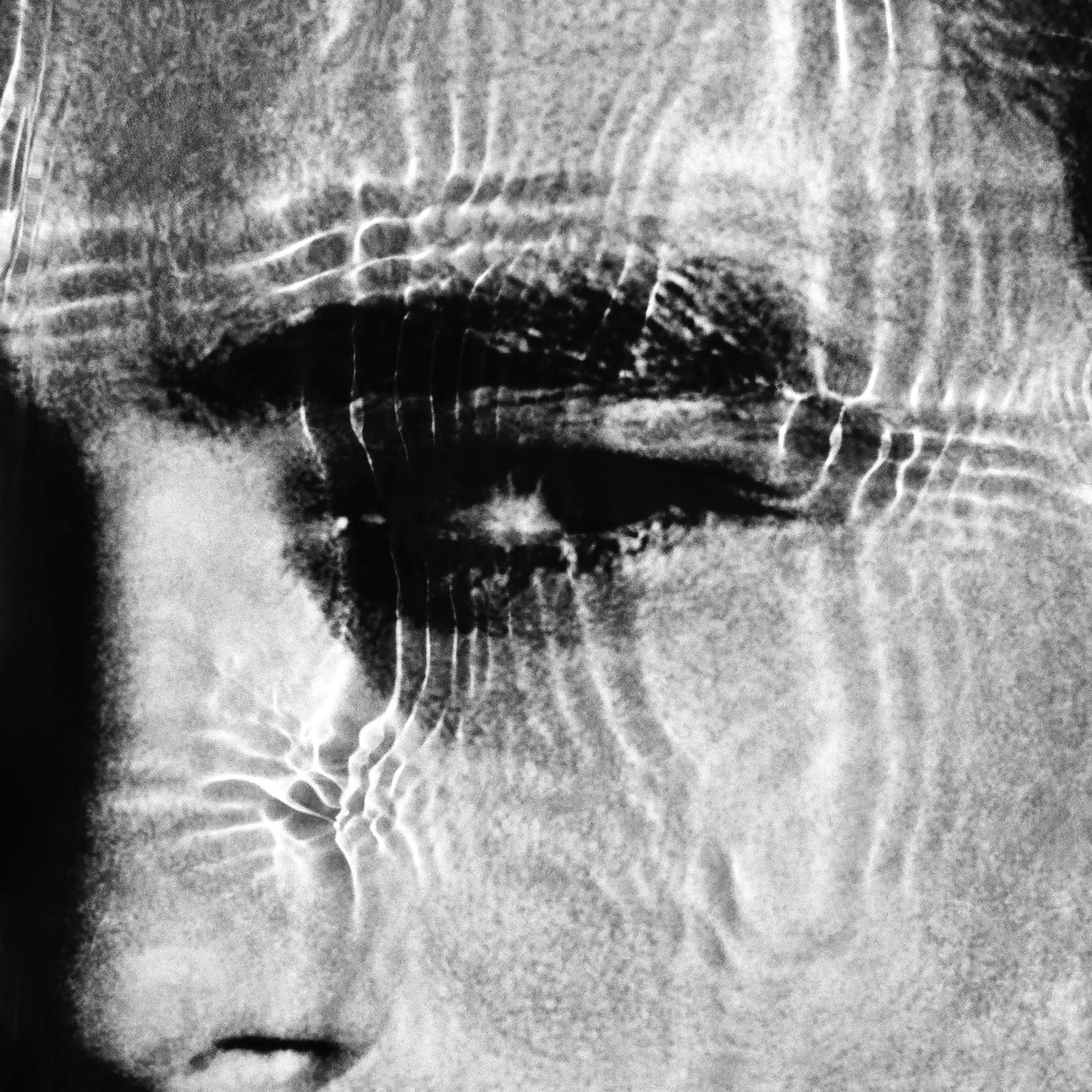

For Italian fashion photographer Alessio Boni, New York was a gateway to his American dream, which altered his life forever. In a series of highly personal works, made with his own unique process, he explores an apocalyptic clash of cultures.

Plus, an exciting young British artist receives a retrospective, Marcel Dzama's whimsical drawings take a political turn in L.A., and more gallery openings.