Annie Leibovitz Shares Her Vision in Monaco

The newest gallery openings this week, including the dark side of the American dream, traditions of Aboriginal Australian painting, a cheeky photographer, and more.

The late legendary French couple Claude and François-Xavier Lalanne worked separately but exhibited under the family name: Les Lalanne. Celebrating the 60th anniversary of their first show together, New York’s Kasmin gallery has staged an incredible show with rare, often fantastical pieces. On this special episode, Dan speaks with guest curator Paul B. Franklin about the legacy of this dynamic duo.

TRANSCRIPT

Dan Rubinstein: Hi, I’m Dan Rubinstein, and this is The Grand Tourist. I’ve been a design journalist for more than 20 years, and this is my personalized guided tour for the worlds of fashion, art, architecture, food, and travel, all the elements of a well-lived life. To celebrate the beginning of season 10 of The Grand Tourist, we have a special double feature along with our main episode with designer Kelly Wearstler. This week I’ll be toasting the new season at Kasmin Gallery in New York. So I figured I would take some time to delve into the incredible exhibition there called Les Lalanne: Zoophites. If you’re an observer of luxury interiors and the world of auctions and collecting, then the name Les Lalanne will sound familiar. You may know the sculptural work of the late French couple, which has consistently broke records at auction houses around the world. You probably know their sheep, fuzzy life-size sculptures that double as adorable seats that, for a while, have been seen in just about every magazine around.

The term Les Lalanne refers to a married couple, Claude and François-Xavier Lalanne, both with their own careers and aesthetics, who exhibited together under one name. While their work was different, themes of nature with a fantastical twist were a common theme. A metal rhino as big as a small car, an ape holding up the surface of a console table, a bench made from vines, and more. Always elegant and often surreal, the works of Les Lalanne have been copied widely. For this show at Kasmin Gallery, rare pieces on display come from the couple’s eldest daughter, and the show celebrates the 60th anniversary of Les Lalanne’s first show together. I sat down with the show’s noted guest curator, Paul B. Franklin, an American based in the south of France, to chat about the legacy of a couple that changed the art world forever.

(MUSICAL BREAK)

And before we get to the exhibition, I wanted to learn a little bit more about yourself. And for most of your career, you’re one of the ultimate scholars of Marcel Duchamp. How did that happen? How did you become the foremost expert?

Paul B. Franklin: A little by happenstance and just sheer tenacity. I wrote my dissertation on Duchamp in the United States, and during the research period that I spent in Paris, I had the fortune of meeting his stepdaughter, Jacqueline Matisse Monnier, who ran the Duchamp estate, and she quickly adopted me, if you will, and I eventually assisted her in running the estate and, on her suggestion, published a scientific journal devoted to Duchamp for 15 years. So I had a long-standing relationship with her and have been passionate about Duchamp since the 1990s, when I did my dissertation work.

And obviously, anyone who took an art class in college or even in high school knows the famed urinal and dada, and what is art? And this is the ultimate example of like is a urinal where you write your name on it, is that art, and so on. But after studying him for so long, what would you say is the number one sort of piece of information that if you could sit down any sort of art student and sort of shake them and say, forget about all of that, this is why he’s so important, what would that be?

Duchamp opened the door to the modern world, and he encouraged other artists to take risks and to believe in themselves. And that’s the lesson that Duchamp has to teach us. And it’s the reason that his work still resonates with so many different artists, so many different kinds of artists in so many different places in the world.

And obviously, there’s a lot of similarities when we talk about surrealist qualities between Duchamp and Lalanne. And for the totally uninitiated, if I ask you who were Claude and François-Xavier Lalanne, who are they?

They are an artist couple born in France. François-Xavier started out as a painter. He went to art school. Claude started out doing window design in Paris for fashion boutiques like Christian Dior, and that’s how she met Yves. Saint Laurent, for instance.

Who collected their work, right?

Exactly. Who were very, very major collectors of the Lalanne’s work with Pierre Bergé, Yves Saint Laurent’s partner. And they had both been previously married and met while they were married to their first spouses and became a couple in the early 1950s, and then started collaborating together, 50s, and exhibited as a unified artistic couple beginning in the early 1960s. And they basically worked in sculpture, mostly in metal. Claude began working in copper, and François-Xavier as well. And then they moved on to working in bronze.

And I guess one of the things that might confuse people is that they together were known as Les Lalanne, but they worked separately with their own studios and they were not, and anything that they did together, there are a few collaborative pieces in the show, which we’ll get to later, but they did operate separately, but also as a collective of two people.

A collective of two people, absolutely. In 1966, they decided to adopt the collective denomination, Les Lalanne, which is a traditional, just a French plural like the Smiths or the Jacksons. And they exhibited under that collective name for the rest of their lives. And even after François-Xavier died, Claude continued to exhibit his work next to her own work under the rubric Les Lalanne. There’s something really ingenious and beautiful about that decision. Beautiful because it’s an act of love, because what it does is it ensures that neither artist gets left behind. And if they’re consistently demanding to be exhibited side by side, one artist doesn’t become famous while the other disappears and becomes jealous.

And because Claude lived longer than her husband, she kind of became maybe a little bit more famous in the past 20 years or so while he passed away early. But he was definitely the more famous one in the past. Is that right? Is that fair to say?

That’s very fair to say, and I think that there are a couple of reasons for that. First and foremost, he was a man, and she was a woman. She was the wife, he was the husband. François-Xavier also was much like Duchamp, a very seductive personality. He was a real punster, so he had a gift for language, and the French adore that.

Okay, how so? Give me an example of a pun.

Most of his titles in fact are puns.

Oh, okay.

So for instance, in the show, we have a console table which is supported by a gorilla, and it’s called the Gorille Consolé. So the word consolé is the word console with an accent. And consolé, in French, also means consoled. It’s the console gorilla who is consoled. Okay. And his titles often sort play with the similar resonances of French words.

Oh, I see. Okay. That definitely lost on me.

No problem.

I mean, such a big part of it is that their love of nature and natural forms, and part of this legend goes back to François-Xavier, the origin stories he worked at the Louvre, right? Or something like that.

Absolutely.

Tell me about that, how the natural world kind of came into this.

First of all, he was brought up in a region of France at the city of Agen, which is sort of in central Western France. And he was around nature all the time. He was an active hunter, for instance. His eldest daughter, Caroline, told me a story of how he taught his daughters how to fish without their hands. So they would stand in rivers, and he showed them how to capture fish with their bare hands. So he had this very intense, visceral connection to nature, which is something that naturally evolved when they moved to the country in the late-1960s, about an hour south of Paris. He explored that love over and over again through different animal forms. And he’s intrigued by the way that wild animals have this incredible ability to sort of disappear when they are threatened by remaining utterly motionless.

And he talks about seductive aspects of that talent, if you will. And you see that in his work, his animals have these very posed, very stationary, very majestic, and regal airs about them. And I think that that comes from his observations in nature and almost a sort of idolization of the animal form. So while he’s working with animals, Claude is much more interested in plant forms, whether they’re vines, whether they’re leaves, and things like that, both wild plants and domestic plants. She was a gardener, so it’s no accident that one of her sort of first emblematic plant motifs is the cabbage, which came out of her own vegetable garden. So their love for nature is a sort of extension of basically just their love for the lived environment in which they existed.

And obviously one of the most famous pieces from them are the sheep, right? Which kind of, there’s a beautiful, lovely little vitrine at the exhibition where there is a magazine article, I think it’s from Life magazine, is that true?

Life magazine.

Life magazine showing sort of them at home with this sort of flock of sheep. And there’s a bed that looks like a duck, and it’s very sort of fantastical and luxurious and hip and cool without being transgressive, and I guess today we might kind of roll our eyes, but back then it was so radical. Tell us about the sheep and how that actually kind of factors into the story.

François-Xavier had a sort of very basic premise when he decided to make the sheep. And it’s a premise that also inspired him when he did his first rhinoceros the year before he did the sheep. He said, it’s easier to bring the country into your home than to force people to go to the country. So he’s interested in breaking down boundaries. And Claude is very interested in the same thing. And that’s one of the reasons that they grow out of surrealism. This sort of socially accepted idea of the division between urban centers and nature, between animal and vegetable, between flora and fauna, between human and animal. They sort of turn all of that upside down. And the sheep were his first big splash in the Parisian art world in 1965. And he went on to make various iterations of the sheep, even the last iterations in cement, so that you could actually exhibit them outside in your garden in the country.

So he sort of brings the sheep back to the country at the end of his career. So the sheep are sort of a way of landing squarely in the middle of the Parisian art scene in the mid-1960s. When we have this movement called Nouveau réalisme, which is a sort of French parallel to pop art, where you have people like Jean Tinguely, and Niki de Saint Phalle, and Daniel Spoerri, who are bringing art into the lived environment, specifically into the urban environment. And the Lalanne sort of turn that on its head, and they bring the sort of countryside into the city.

And speaking about this particular show, tell us a little bit about the title and how the show came about and what your approach was to the show.

The show is titled “Les Lalanne: Zoophites.” And the word Zoophite is a sort of antediluvian word that was used beginning in the 16th century and up until the 19th century to describe mostly a marine invertebrate that lived in the sea who possessed the appearance and certain aspects of plants. So, for instance, coral or sponges, they exist between these two worlds, and it’s a beautiful metaphor for the Les Lalanne’s own work. So when they had their first joint solo show in 1964, François-Xavier came up with the word Zoophite as the title of their show. So we decided, 60 years after their first joint solo show, to pay homage to that initial exhibition by re-appropriating that title for this exhibition.

And the exhibition, the pieces come mainly from the collection of their eldest daughter, correct?

Yes. The pieces come from their eldest daughter, Caroline. As I told you, the Lalannes both were previously married, and in their first marriages, they each had children. So François-Xavier had a daughter, and Claude had three daughters, and her eldest daughter is Caroline. And Caroline allowed us to borrow all of these works that are in the exhibition from her personal collection, which come directly from the collection of her parents.

Did they have kids together?

They had no children together.

Okay. When did they start? When did they first meet? At what stage in their life.

They first met. Okay, so Claude is born in 1925, and François-Xavier is born in 1927, and they meet in 1953. Okay. So they’re just beginning to arrive at middle age. They’re not so young, but they’re not old either. And they get married in 1962.

And one of the highlights of the show is the fact that you have these rare pieces that they worked on together. First of all, how rare are these collaborative pieces, and which one would you say is your favorite?

The fact that they had a sort of joint career for over 50 years and produced only a handful of collaborative pieces. The fact that we have three of these collaborative pieces on show is pretty significant. As you said, they worked side-by-side in their studios, which were part of their home outside of Paris, so they were around each other all the time. And Claude talks about the fact that they critiqued each other regularly, which is a very common practice for artists and even for artist couples. But it was very rare that they co-signed work.

Do we know why? Did they just, like any couple, they just didn’t want to get into it?

I don’t think that they really wanted to get into it. And I think that maybe they were too respectful of their own, independent erve to tread on the territory of collaborating. They already exist as a collaboration under this title Les Lalanne. And I think it’s actually, it’s more intriguing that they did not regularly collaborate because it really forces you to think about what collaboration means in the context of an artistic couple where they live under the same roof. They have similar but very visually distinct aesthetics and can nourish individual artistic outputs without having to actually put their hands on the same object all the time. There’s a way in which collaborating on single objects would’ve been too easy.

And one of the highlights is this, if I have the name right, the “Grand Chat polymorphe” or?

The Grand Chat polymorphe.

“The Grand Chat polymorphe,” yes.

The large polymorphous cat.

Right. How big is this cat? Because I’ve seen it. It’s quite big.

It’s 16 feet long.

Wow, okay. And it’s gold-plated?

It is in bronze.

It’s in bronze, excuse me.

It’s in bronze. This version. This version is from a-

It’s a highly polished bronze. You could, it’s almost golden looking.

It’s very golden looking. It’s very patinated, as you say, in sculptural terms.

Right.

Yes.

And describe for listeners like what it looks like and how this crazy thing came about.

How this crazy thing came about. Polymorphous means multiple. Okay. So it has elements of various animals in its body. So it has the head of a cat, it has a sort of generic mammal’s body. It has the feet of probably a pig or a cow. It has eight teats on its stomach, so it’s supposed to be seen as a female. Although the title Chat, which is cat in French, is masculine. So we’re dealing with sexual polymorphism in the work. And that’s the play on words that François-Xavier is so talented with. It has the tail of a fish, and it has two side panels that open to create wings. So it looks like it’s a bird.

Got it. But it’s functional also because it has this compartment.

It is. It has a compartment under the wings, in the inside of the abdomen, which served as a bar. The original version from the 1960s was designed as a commission for a French architect for his very posh Parisian apartment. And François-Xavier said, “I designed it to be just a little too big for the apartment.” So he’s purposely making it on this out-sized scale so that it sort of makes the compartment look small. So it’s sort of this wonderful little mocking gesture to this wealthy Parisian couple who have this very beautiful apartment. And you were supposed to use it as a cocktail bar. And there’s a lovely play on these sort of swollen animal teats of this cat who would’ve suckled her kittens. But François-Xavier offers us the adult equivalent of mother’s milk in the form of alcohol.

And François-Xavier passed in 2008 and Claude in 2019, not that long ago. Did you ever get a chance to meet either of them in person?

Yes. I met Claude several times because she was very close friends with the Duchamp family. And when I was working with Duchamp’s stepdaughter, I used to take her over to Claude’s house in the neighboring village to visit with Claude. And Claude would come to Jackie’s home as well.

What was she like?

What was Claude like?

Yeah.

Incredibly elegant. So she would be dressed in her sort of classic work clothing, but always have a sort of fancy scarf around her neck and her hair pinned back. She sort of was effortlessly elegant. It was never a sort of forced elegant, it was never over the top. It was always very understated. And her home was very much like Jackie’s home. It was a home in which they lived with their art. They lived with their own work. So the preciousness of their art objects was never something that they took too seriously. François-Xavier and Claude always said, art is far more approachable and understandable when you can touch it, and live with it, and use it.

Why do you think their work is so beloved?

I think their work is beloved because it’s at once incredibly familiar or seemingly so, but when you get close to it, when you really spend time with it, it offers you surprises. And I think that that’s what people like. And in offering you surprises, it actually offers you a kind of joy and a kind of euphoria that we don’t often get with modern or contemporary art. It’s not overly political. It’s not work that is about angst. It is work that’s about a kind of joyfulness in living. And it encourages you to sort of understand the privileges of being in the moment. And that’s what I like about their work, that it’s both sort of seemingly approachable but also jarringly unfamiliar. And that’s what makes it sort of part of this history and legacy of surrealism. The unexpected.

And if you had to describe the work of Les Lalanne in three words, what would you say?

Dazzling, surprising, and joyful.

(MUSICAL BREAK)

Thank you to our guest, Paul Franklin, as well as to everyone at Kasmin Gallery for making this episode happen. The editor of The Grand Tourist is Stan Hall. To keep this going, don’t forget to visit our website and sign up for our newsletter, The Grand Tourist Curator, at thegrandtourist.net, and follow me on Instagram at @danrubinstein. And don’t forget to follow The Grand Tourist on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you like to listen, and leave us a rating or comment. Every little bit helps. Til next time!

(END OF TRANSCRIPT)

The newest gallery openings this week, including the dark side of the American dream, traditions of Aboriginal Australian painting, a cheeky photographer, and more.

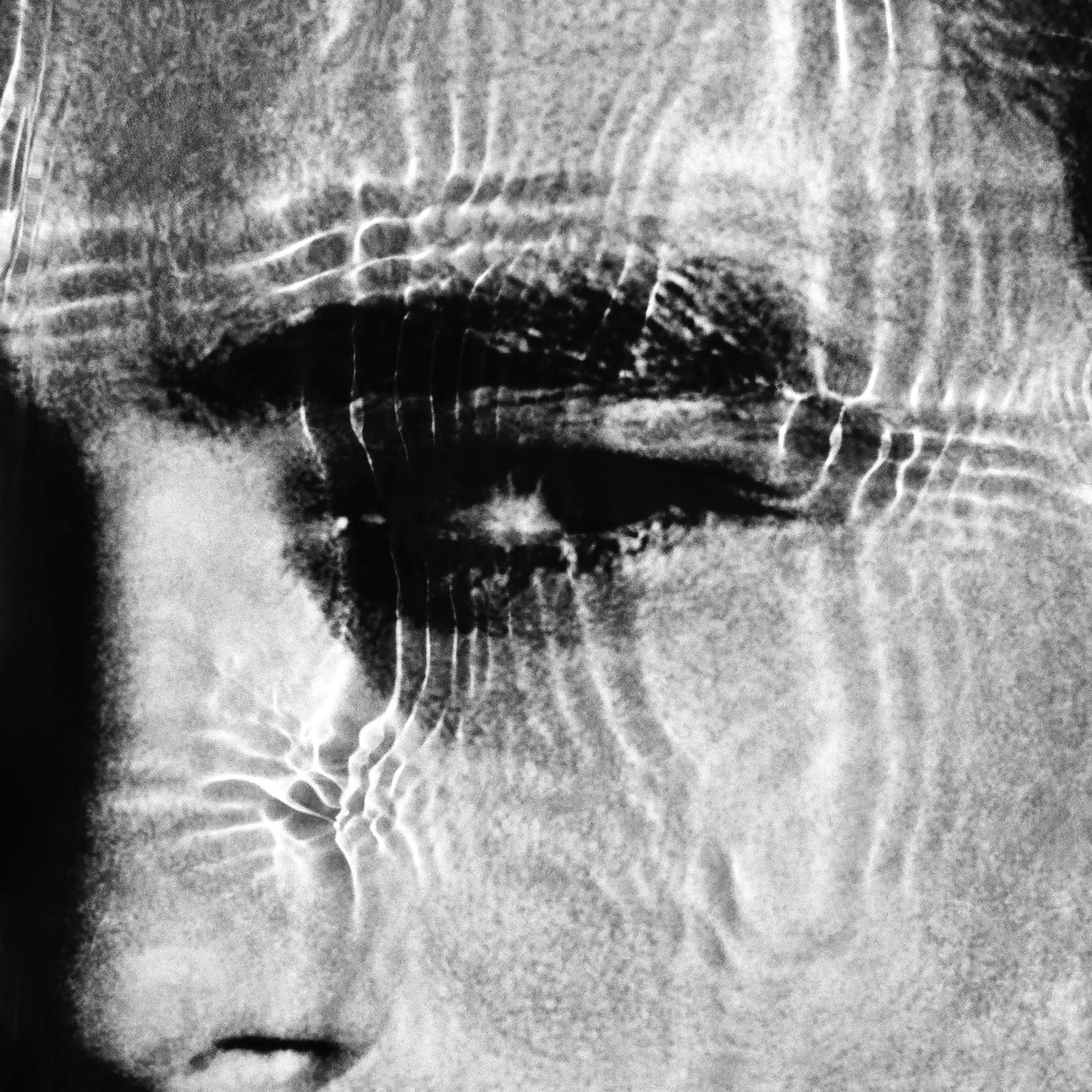

For Italian fashion photographer Alessio Boni, New York was a gateway to his American dream, which altered his life forever. In a series of highly personal works, made with his own unique process, he explores an apocalyptic clash of cultures.

Plus, an exciting young British artist receives a retrospective, Marcel Dzama's whimsical drawings take a political turn in L.A., and more gallery openings.