Annie Leibovitz Shares Her Vision in Monaco

The newest gallery openings this week, including the dark side of the American dream, traditions of Aboriginal Australian painting, a cheeky photographer, and more.

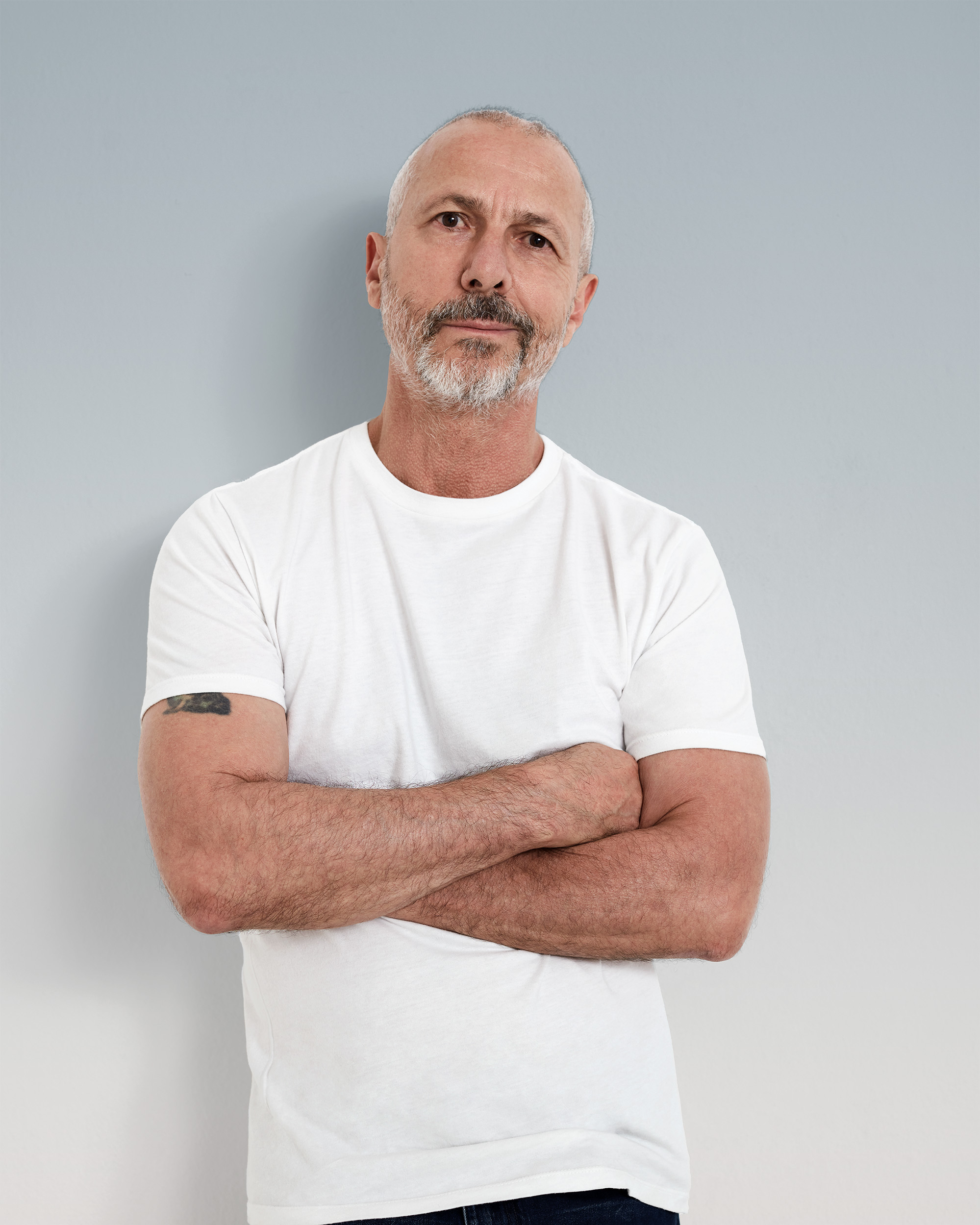

As one half of the famed Campana Brothers, Humberto and his sibling Fernando ushered in a new era of design that blended craft, industry, and notions of ecological and social responsibility. Following the tragic passing of Fernando in 2022, Humberto carries on today as the head of Estúdio Campana. On this episode, Dan and Humberto chat about growing up in a conservative Brazilian household during the dictatorship, his new exhibition at Friedman Benda gallery in New York and his recent collection for Paola Lenti, the future ahead of him, and more.

TRANSCRIPT

Humberto Campana: I can create beautiful things, constructing things with… It’s not necessary to be a very developed industrial country to be a designer, because I’m a survivor also.

Hi, I’m Dan Rubinstein, and this is The Grand Tourist. I’ve been a design journalist for nearly 20 years, and this is my personalized guided tour through the world of fashion, art, architecture, food, and travel, all the elements of a well-lived life. Brazilian designer, Humberto Campana, is one of the most influential creatives of the 21st century. For more than 30 years, his work was instrumental in the evolution of design as we know it today. Of course, as many of you might know, until the tragic passing of his brother, Fernando, they were known simply as the Campana Brothers. Their work often shocked and tickled those with strict modernist tendencies. In the world of the Campanas, stuffed animals could be sewn together to make an armchair, scraps of fabric could be turned into collectible works sold for princely sons. Fernando died at age 61 in 2022, and his brother, Humberto, now carries on their legacy, not to mention the impressive machine behind him today called Estúdio Campana.

As you’ll learn on the show today, Humberto didn’t plan on being a designer at all. His breakout work in the ‘80s with his brother, the so-called Uncomfortable Chairs, were iron works with spikes, swirls, and sharp edges. It certainly got people talking. Their next star design, which we’ll also speak about, was the Vermelha Chair, where a simple metal frame is wrapped endlessly with a bright red cord to form a seat. Again, it challenged the notion of just what design was really all about. And if you’ve ever been told by some designer looking for fame because they hired local workers in their hometown to make their glamorous products, they probably got that idea from the Campanas. To this day, his studio in Brazil trains local craftsmen to produce their highly collectible works, often sourcing mundane objects and materials, spinning another man’s waste into design gold.

In 2022, the Italian brand Paola Lenti, known for their colorful outdoor furniture, collaborated with the brothers on a massive, one-of-a-kind, amorphous seating blobs in bright colors, called Metamorfosi, sewn together from industrial fabric scraps. Today’s Estúdio Campana tackles its first solo show with Humberto at the helm, that just opened here in New York at Friedman Benda Gallery, called On the Road, that features sofas made from upcycled polystyrene used in packaging, along with leather and sheep skin, as well as mirrors framed in aluminum sourced from industrial scraps.

I caught up with Humberto from his studio in Brazil to talk about his youth as a gay kid in a conservative family during the trying years of Brazilian dictatorship, how an article in Domus Magazine turned the Uncomfortable Chairs from a joke into the hot new thing in design, the story about how their first stuffed animal chairs came to be, and more.

(MUSICAL BREAK)

So I wanted to start with you in the beginning. I read that you were raised in Brotas, which is about 150 miles northwest of Sao Paulo, and I’m wondering, what was life like for you there as a young child? What do you remember?

It was my treasure, as well my hell, both, because since I was a kid, I was born with this intuition, with sensibility to arts, but never… My family was a small bourgeois family, my mother was a primary teacher, my father a agronomic engineer, so we are very… Also, during the military dictatorship in Brazil, so it was [inaudible 00:03:52] completely away from everything. I didn’t like to be there, but at same time, I had to create my own universe in order to make my own toys.

So the nature was gorgeous there, it’s still gorgeous, so my contact with nature was very close, and this was very important to me in order to work on this. I like to make gardens, to plant trees, to create houses in trees with bamboo, making swimming pools in small creeks with rocks, so since all the beginning, my hands on. At the same time, we have a movie theater there from a Italian guy who moved to that small city, and he had a good taste, so he brought all the movies from [foreign language 00:04:52], Western American, Western [foreign language 00:05:00]. So in the evening, I was in the movie theater, during the day, it was very boring, I start to create the sceneries, things that I saw in the movies, with Fernando, my brother. We were very close.

Yeah. And you mentioned, obviously you said that you made toys for yourself, and obviously knowing your work now where you work with unconventional materials, obviously, I’m curious, what was your favorite toy that you made when you were growing up?

It was a tent, an indigenous tent, because I want to be indigenous. I refuse to use shoes to go to the school, and I want to live in Amazon because the trees or the indigenous artifacts. So one day, my father gave me a structure of a cathedral. My father made a cathedral, like the Brazilian cathedral in the ‘60s, the church, and he gave away when finished the [inaudible 00:06:18]. So I covered with straw that cathedral, my indigenous house there.

When we talk about mid-century modernism in Brazil and the ’60s and everything, how would you describe the culture in Brazil at the time, what was that like? If we were to go in a time machine and go back to when you were 13 years old, how would you describe the scene in Brazil?

Well, I wasn’t conscious about that, but there was in here this magic of Brazil is the country of the future. When I was 13 years old, Brazil was inaugurated in the ‘60s, so it was a huge development, industrial house development, in Brazil, the capital moving from here to Brazil, all the companies, the Chevrolet, Ford, come to Brazil to construct cars and trucks, the industrialization. So we need to do furniture for all Brazil, and they had apartments in huge [inaudible 00:07:33, so it was a huge hope in the air. All the modernist masters coming to Brazil from the Second World War, running away from the Nazis, they established here in Sao Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, so they brought all this modernist spirit in Brazil that’s still very present. If you go to downtown Sao Paulo, it’s a museum of modernist buildings, all abandoned, it’s beautiful.

Yeah, it was very interesting, very beautiful, that moment, until the dictator in the ’64, so they start already going to other places, things start to be harder here.

And what was life like for you under the dictatorship?

It was very scary, very, very scary, because some people from my family had disappeared. I was 14 years old—

Really?

Yeah. So my father told, “No, never go to the student [rallies].” I tried to be not involved with this, because it was really… People talk about you, if you on the phone, if they listen, conversation. It was very, very scary.

That might even connect to my next question, how you studied law before going into art and design, and with you and your brother, and your brother, I think, started architecture. Why did he study architecture, and why did you study law? How did that happen?

Well, myself, I studied law, because I didn’t want to… I was completely lost when I had to make up my mind to go to a school, a university, so I moved to Sao Paulo, and I choose the easiest career, law, because there was no mathematics. I had a huge problem with mathematics. So not to be an architect, that I would love to be, because there was necessarily a lot of knowledge about mathematics. There is no computer at that time.

So I went to the school, but the first day of law, I told to myself, “This is not my family, this is not my place.” But I stayed there five years in order to… And when I finished, I gave my family the diploma, the graduation, and I told to myself, “I want to construct my life with my own hands.” Because I always sense that, and at that time, was trying to be a sculptor. I always have great passion for sculpture, all the [foreign language 00:10:42], modernist sculptors. So I want to be a sculptor when I moved from law to my career.

And I read that you started with doing some of your own design projects for friends, and that that’s how things started with your own studio. Were those first projects design projects, or were they more, as you mentioned, sculpture, or what were they?

No at all. Because I moved to Bahia when I finished, because Bahia in the ‘70s, it was a place for freedom. Mick Jagger, Janis Joplin, Rolling Stones, they always went there in Salvador. And I moved to a beach, near the beach, Itabuna, a place near the beach. And a friend of mine from my hometown was living there, so I live with him. He was an architect, so he told me, “Why don’t you make some frames for mirrors for my clients?” So yeah, let’s do it. I went to the beach, start collecting seashells, and creating frames of mirrors with seashells. And the first mirror was very nice, it was very naive, of course, but well done, well-made, and I liked it.

I stay one year there, then I moved back to Sao Paulo, and in order to making a living, I start to selling all these objects in shops here in Sao Paulo. And one day, Fernando, my brother, he came from Christmas delivery, at the end of the year, he was finishing the architectural, and he went to giving a helping hand, this was ‘84, and he kept going. And he had good taste, he had studied architecture, so he start to change all these very [inaudible 00:13:04] objects, in order to good taste, make some cleaning. And then, we start doing things, why don’t you go deeper into this? And then, ‘84 was the turning point from law, from the crafts, from what I am today.

But I’m still consider myself as an artisan, I love to work with the hands. I don’t refuse that past. For me, it’s important to bring that past, because it is what I am now, it was what I am now today.

And when your brother joined you, was that a natural thing at first? Did you guys fight at all, disagree in the beginning about what you were going to do and what direction you were going to take?

A lot. All the time. But it was wonderful because we’re friends. We are very good friends. Yeah, we quarrel a lot. And that was very good because our quarrels were in order to make a good project. We tried to know this is better this way, and it was magic, very magic, our relationship. I remember at the end of the day he brought a little of pot and we smoked, then we started drawing, listening to music and it was very good because it was fun. Two kids playing, and until last year it was like this.

And the beginning when you guys start making furniture together, you’re using these commonplace elements. They’re not seashells, but you’re using these other pieces and your style starts to emerge. Do you remember, was there ever a point where you and your brother were working together where something clicked, where something started to really become something I would recognize today?

Okay. Well, it was the year of ’89 when at that time I was taking sculpture courses on iron welding, and just make appearances. It was the year of ‘88 when I did a trip on Colorado River, a journey of 15 days rafting in the Colorado River with the group of Esalen Institute. It was a workshop with Esalen Big Sur to go rafting in the Colorado River and sleep in the desert. It changed my life, this journey. And one day my boat flipped.

Flipped over.

Yeah. And my lifeguard was open and I got inside the whirlpool. Everybody moved, they saved themselves. And I saw that going there and myself staying in that whirlpool, that I was got that. And miracles, I got safe. And the same day, I made a design of a chair on iron that was a spiral, a vortex. So I came to Brazil, I realized I made this chair on iron myself, and I cut a very thick blade of iron with fire. The piece that came out from this chair, Fernando made another chair. This is our beginning, very, very beginning.

And ‘89, eighties was the end of the military dictator here in Brazil, so it was a moment that we could speak, we could express ourself. So me and Fernando, we’ve designed a collection of chairs with the title Uncomfortables. Very rest, very brutalist, very anger because it was a vomit against all the military, the hate that we have of these people in Brazil. So it was a vomit because also we didn’t want to follow, we are looking for the Brazilian roots, the imperfection, the chaos, all these elements that consists the Brazilian diversity. We brought in that collection and that was our beginning, ‘89, starting USA in the Grand Canyon, the project, and then Sao Paulo with the title.

Was that trip on the river, was that your first time in the United States?

No, no. No. I had a relationship with an American, a guy for 26 years. So I was used to going a lot to USA and traveling to Santa Fe by car, Yellowstone and all these amazing places in USA. Yeah, I love its beauty.

(SPONSOR BREAK)

And when you first created your Uncomfortable Chairs, which to this day, I think you could show them as new and no one would be the wiser. They would look new today, which I think is a testament to them. With those Uncomfortable Chairs, I’m curious, did you have any pushback at the time? Did anybody look at them in the art world or the design world and say, “Oh, I don’t get it, I don’t like it.” In the first couple of years when you’re doing new work, but you’re not famous yet, did people push back on you at all? Yeah?

A lot. It was very controversial because first of all, meanwhile we are doing those chairs, we are still doing the baskets, the shelves. It was very bipolar because one side, very looking for the future, and the other very commercial, very bad taste in order to sell. No, all the time. And it was the turning point, it was a journalist, Italian journalist, Marco Romanelli. He came to Sao Paulo to do a lecture here at MASP, invited by Pietro Maria Bardi, the husband of Lina Bo Bardi. He came in, we brought our furniture to him and he made an article on Domus, six pages about our work. So it was a necessary Italian to put our naming in the design community in order for Brazilians to start to pay attention, respect us, because we were considered one-of-a-kind. And the people that joke with us, the Uncomfortable Brothers, the irony with us.

When you were first starting out, were your parents trying to tell you, “Listen, you have a law degree, go be a lawyer, what are you doing? Is this crazy?” With your brother as well, because obviously the two of you working together, that meant the brother was also in the same building.

Fernando was easier because we’re eight years age difference. So I opened for him the path. My family at the time, they didn’t speak with me, we stayed two years without speaking. They were very mad and sad with me, but it was necessary to cut the cords with them. Imagine, because they were very conservative. A family with military, with doctors, engineers, teachers, very Italian. The Italians that came from Italy, from fascism. There was this Catholic… And myself, gay, that I never talked about them that I was gay, tried to hide all these years. It was very difficult for me. I didn’t like to play football, I like to read, to plant trees, to construct objects. In my hometown, people watched me with another eyes. It was a lot of bullying that I suffered for being very sensitive.

Yeah, yeah. Wow. And in 1993, you guys had this breakthrough again, in, I would say, the greater design world with the Vermelha chair, if I’m pronouncing that correctly, which is a metal frame with hundreds of feet of rope, bright red rope kind of wrapped around it that creates a seat. And it was eventually manufactured by Edra, but I’m not sure how that chair happened because that seems to be a step beyond even the Uncomfortable Chair. And it seems to be really another connection, which we would say, “Oh, obviously that is such a [inaudible 00:25:48] product.”

1993 is the base. We did an exhibition. I don’t remember the name, but it was the base of what we do today, because in that exhibition, there was a lot of materials. Cords, cardboard, TV antennas, aluminum, charcoal. All these elements were in this exhibition. It was the base, what we do today, because we are the Uncomfortable Brothers, and we want to bring comfort. We don’t want to stay in this easy formula of cut a piece of metal. No, I want to go further, go deeper. And we choose the materials, then our eyes start looking for comfort, so we start looking at materials that could give comfort.

Comfort, very light like the aluminum wires or the aluminum TV rods or cardboard or cords. And one day we are walking around in Sao Paulo, we bought a bunch of ropes, but without knowing what to do with this. I like to have a flirt with the material all the time, I buy materials. And we bought a bunch of ropes, then we brought to our studio this bunch of ropes. Deconstructing front of our eyes, me and Fernando. And when we stared to the other, “Look, oh, this can be a chair. Imagine, Fernando, if I construct a metal structure and we start weaving this.” And we did it. So we did a metal structure and I started weaving it, but not regular because I hate mathematics, I hate rationality. And I went to… No, this is possible also, no? To deconstruct, to be chaotic, like something melting. And that was a very great impact on us, on people’s eyes also.

I can only imagine what showing the Vermelha Chair for the first time at the Salone next to all of these Italian designers… And I can only imagine. “And I’m from Brazil, and here is my chair, and it’s made from just wrapped-up rope.”

It was amazing.

I can only imagine.

One year earlier, Marco Romanelli, the journalist, he created a round table at Palazzo Reale in Milano and invited all the masters of minimalism design. Konstantin Grcic, Sebastien Baert, I don’t know who else, all the German minimalism. And we, Fernando, we brought… Our talk was about cardboard chairs, charcoal. Charcoal. They kind of look at us with irony. They didn’t say nothing, they just looking at us. I remember the smile, ironic smiles on their faces. And we are still here today. I am still in the design scene. You are making interviews with me. Because they looked at us like, “Oh, you are going to disappear soon.” It was very funny. That was the reaction from the minimalist designers.

So you’ve had this incredible career, and obviously this is a question that everybody gets asked. Have you come up with your own definition of the difference between art and design?

I don’t… No, never. Because I’m a storyteller. My work is about making portraits of the experience that happens to me, things that attracts my eyes. And then I want to tell that experience or that moment. I want to crystallize those images or experience catharsis into objects. But I never want to try to define myself. Even today, it’s something out of my… It’s a way that I do in order to have mental equilibrium for life has… You know, the world, now that is so bad. So Argentina, that horrible president was elected, is going to be the second Bolsonaro. And I told to myself, “If I construct my life, if I have, nothing will change with me.”

Because I am going to be serious and focus on my work and this will save me from this, the planet. You know, all this. I try to do my best, planting trees, I’m constructing a park. If I can speak to you later, if you know a foundation in order to preserve nature and the design heritage. So yeah, I try to work and don’t pay attention. Of course, I’m very sad, all these things happening in front of my eyes and it’s so sad. Yeah.

(SPONSOR BREAK)

And when it comes with these sort of stuffed animal chairs, which may be in the Encyclopedia of Design in the future, under the name of you and your brother, this is what might be seen as the classic chair, I’m curious how that started. How did you decide to do that and how did that happen?

That was the year of 2000. The beginning of this century. We’re looking forward to create a furniture without the traditional methods of upholstery. That was the seed in my mind, looking, I don’t want a metal structure. And then one day there is a guy selling plushes, passed in front of our studio with a bunch of alligators, lions, whatever, like a Carmen Miranda, you know? Red hat. And I looked to… I bought all the plushes. I brought to the studio, start to stitching one to the other myself. And Fernando, he designed the metal also. Again, Fernando was the designer. And I did one, I made one, then start to selling to Moss. Murray Moss. He was the one who started to selling at Moss, which was a fantastic shop at Greene Street. And that start to be a big success. And it was very good because at that time a guy from Canada came to us, before…

It was a parenthesis. I’m sorry to… He asked us, “I’m writing, I’m doing an article in a magazine in Toronto,” I don’t remember. “And please would you like to send all your projects that were never produced?” And me and Fernando, we sent to him this project. And he started doing, copying this and selling at Moss, at Murray. And there was a question, someone, a magazine here in Brazil start to looking who had copy who. And it was proved. We have all the emails that we changed with… Emails, no. Fax. At the time was fax. And we proved that our…

And at the same year Edra, the Italian brand, was supposed to produce these plush chairs, and they cut this. And that was very good for us because from this chair, we start to producing the chair in my studio, we start to earning money. Because up to that chair, life was very difficult for us. Still no car, bank, no money at bank. And with this chair, we start to produce in my studio. Then it start to bring people from fashion to manufacturing, and the studio start to being a kind of laboratory. Start to getting their actual status of a laboratory of research. And Moss start to selling more and more.

And I’m curious, you’ve had such a prolific career. And as you explain how the stuffed animal chair, when it started to take off and you became more of a laboratory, and you became more of an art studio rather than pursuing design, as production design, that was when you really started to become comfortable or just even to make the proper living, as you said. That you didn’t have any money before and all that stuff. So I’m curious, was that decision something that you enjoyed? Or did you think, at the time when you first started, that it was a step down? Because before, craft was not as put on a pedestal as we do today. And to see that all of a sudden you’re not going to have your chairs mass-produced, then you’re not making a quote-unquote “real career…” At first, were you like, “Oh no, we’re taking a step backwards rather than forwards”?

It’s kind of this, because we want to be industrial designers. I want to be minimalist. I want to be those guys. We want to be the industrial designers. But you know what’s fun? Because how life writes things in a way of mistakes, but at the end you know is the right thing. I remember Karim Rashid once came to Sao Paulo in a lecture. He told, “No, the Campana brothers are not designers.” Karim Rashid. Well, people kind of was putting us aside. We bothered a lot of people.

That sounds like something he would say.

And today this is precious because I don’t know who I am, which is amazing. I like to create things. Last week was painting the head of my friend who has cancer. She asked me to paint hair, and I love it. I discovered a new way of expressing myself.

I think if you started a hair salon in New York, you’d make a killing.

Yeah. It would be. I love, I really love. I’m going to send to you the video, myself painting.

And I would say even though you’re about this sort of narrative and this sort of idea and communicating your culture, but you still do work in design. I mean, you still have design clients, and especially Paola Lenti with Metamorphosis, this amazing chair and a seating system that is so unmistakably yours. How do you like to work with… Tell me about that project and also how do you like to… I’m sure now, when people work with you in design, they know what they’re getting into and they know what they’re probably going to get. So how did that happen with Paola Lenti and what was that like?

It was fantastic because it was the end of the coronavirus epidemic. And one day she called me, her assistant called me, “Are you interested in working with our things, our fabrics or our materials to create a line of collection in a project that works with a community of immigrants in Milan?” Well, I love that because I was begging for this to communicate that a brand like Paola Lenti can reuse all the… So she sent me three box of fabrics, cords, ropes, whatever, very colorful. For me, it was like a treasure was arriving into my studio, all those beautiful fabrics. It was amazing, such amazing project. And then we start to changing this, the codification, transforming hopes into fabrics. It was fantastic. And we send her back, she start to producing with this NGO in Milan. It was amazing project. And there are two sisters, Paola and her daughter, her sister, and me and Fernando. Was a very good combination. And also to communicate us, to contaminate this project, other brands, in order not to throw away. That was fantastic because I had this possibility, political possibility to show this is possible. So all the material, starting from the cushions, from the upholstery, is all made with the leftovers from the company. It’s a very honest project since the beginning.

And you mentioned something about a park and a new initiative that you have going on that you mentioned. Can you tell me a little bit about that? Tell me about that project.

Eleven years ago, we create an institute to campaign in order to promote the rescuing traditions, manual traditions, promoting giving better income to non-privileged people. We still work today with those peoples, and I was used to teaching favelas here in Sao Paulo, all before the pandemic. And with the pandemic, everything was closed and I move. I start to going to the countryside, my hometown, that we inherited a piece of land, me and Fernando, and it was completely abandoned because I always refuse that, my history in that place. My family has passed away, so no connection.

And I come back there. Well, why don’t I talk to myself and Fernando. We have teach all over the world in schools. We gave workshops. Why don’t we create a pool, a place where people can come here and learn about design, environmental issues? So we start creating pavilions, green pavilions, pavilions made where the plants construct the architecture. So we start doing this, planting trees, and then we are collaborating with a scientist of Sao Paulo University. He’s going to put a laboratory in this place in order to regenerate the nature where there will be a restaurant for people to eat the food that’s planted there.

It is a huge project that we are involved with in order to give away to the city, me and Fernando. The idea is like a foundation where people can make internship about design or the environment. I can send all the information to you, because it’s my future I see myself completely devoted to. There is still six pavilions constructed and there will be more six, because I had a dream in the pandemic that I need to create a link between Italy, my heritage, my family, and in Brotas, Brazil. And I dream about the Etrurian seats. The 12 Etrurian Etruscans cities from the antiquity.

Yeah.

Yeah, because my family came from Tuscany where the Etruscans were there. So I want to make this crazy dream. I’m very intuitive, you know. I had this dream and I want to-

See it happen.

Construct 12 pavilions that symbolize this connection with Italy that opened my doors. And a place where people can learn healing, a place where people can use with no shoes, taste the water, the smell of the plants. Because the animals are going there, so it’s a healing place.

This is obviously a very sensitive question and I don’t blame you if maybe you want to skip over it, but I was wondering if you could share one memory of your brother? In design or not in design, it could be the most simple thing that you think tells us about the kind of person that he was and what he meant to you.

Fernando was always… He passed away at 62 years old. He still taught. He was an enfant terrible. Fernando, he was so older, he want to be an enfant terrible. Yes, he was very stubborn. Yeah, he was amazing because he was a genius, because he didn’t want to be… I love the process, going every day to the studio, working, stay with my people here. No, he refused. He was lazy. He went and he stayed in his house. Sometimes he comes here, “I don’t like this, I like this.” But with fresh eyes, he was not contaminate. So he brought all this energy, chaotic energy. He was very chaotic. There was some lectures that I made with him. In the middle of the audience, he start to, “No, this is not true what we’re telling you.” He used to put me in bad situations. Enfant terrible. He was always acting like this.

And it was amazing because there was a love between us. My family passed away, my mom and dad, but I still miss him because he take me out of the comfort zone every day. To be with him is not a normal day. And he came with ideas. It’s interesting because on other days, I’m working with the material. That on his last days, he was showing to me and I told him, “No, Ferno, this, I don’t like this material,” which is the aluminum leftover. And one day he passed away, and four months later, I had a dream. I was constructing something with that material, and now, I got all this spirit. I’m constructing a lot working with this aluminum from leftovers. It’s fun because he’s present. I feel him near me pointing. It’s crazy, which is good because yeah, life is not about this still. I believe it’s been happening so many things that connect with him. Yeah.

And I am curious, when you talk about this project and creating something in Brazil that connects to your past and to your family’s past, do you think about where the future of your studio is going to go? Have you ever planned the next 20 years of your career? Or do you want to do more things that are rooted in where you are rather than doing what you’ve been doing with projects in different places of the world?

No, since Fernando passed away, more than ever, I’m very strong. It was necessary one year to go to the bottom of everything. Now, I’m coming back with a lot of inspiration, strength. I’m creating a collection for Freedom, a band that are representing New York with new materials, Adobe and aluminum leftovers. The park, next year, we are going to celebrate our fourth anniversary of Estúdio Campana. We start ‘84, so we are working with on a documentary with Francesca Monpeni and Maria Francis, Maria Christina Dedaho. They’re shooting some interviews. We are launching a book about a Campana way of doing things. And also, we are going to open the park part of our… It will be symbolic because all the monies and all the investments comes from my pocket, me and Fernando up to now. And as a big project, we are looking for sponsors, that one day, they will come. I’m positive.

Because I don’t want to earn money with this. I always ask inspiration. If I have inspiration, I’m okay. I have a nice life, a nice studio. I have nice people working with me, but I don’t want more and more. That’s not my goal. I want to be young, mentally young, my goal.

(MUSICAL BREAK)

Thank you to our guest, Humberto Campana, and to Silvia Lunazzi and everyone at Estúdio Campana for making this episode happen. The editor of The Grand Tourist is Stan Hall. To keep this going, don’t forget to visit our website and sign up for our newsletter, the Grand Tourist Curator at thegrandtourist.net. And don’t forget to follow me on Instagram at @danrubinstein. And don’t forget to follow the Grand Tourist on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you like to listen, and leave as a rating or comment. Every little bit helps. Til next time!

(END OF TRANSCRIPT)

The newest gallery openings this week, including the dark side of the American dream, traditions of Aboriginal Australian painting, a cheeky photographer, and more.

For Italian fashion photographer Alessio Boni, New York was a gateway to his American dream, which altered his life forever. In a series of highly personal works, made with his own unique process, he explores an apocalyptic clash of cultures.

Plus, an exciting young British artist receives a retrospective, Marcel Dzama's whimsical drawings take a political turn in L.A., and more gallery openings.