Annie Leibovitz Shares Her Vision in Monaco

The newest gallery openings this week, including the dark side of the American dream, traditions of Aboriginal Australian painting, a cheeky photographer, and more.

A household name in food and fine dining, Eric Ripert has elevated seafood to new heights with his legendary New York restaurant Le Bernardin. On this episode, Dan and the maestro speak about his upbringing in the tiny principality of Andorra, how he cut his teeth in the demanding kitchen of Joël Robuchon, his fond memories of Anthony Bourdain, how his Buddhist faith keeps him grounded, his latest must-own book “Seafood Simple: A Cookbook,” and more.

TRANSCRIPT

Eric Ripert: A complicated dish is a dish that has way too many techniques, way too many ingredients. That to me is not what I like. Le Bernardin, we don’t serve grilled fish with olive oil and lemon juice. It’s much more than that. But it’s nothing wrong about serving good olive oil, lemon juice, and a piece of fish perfectly cooked. So, you can start with that, and then you can evolve and go a bit further and further, and as long as you are confident, you can go very far.

Dan Rubinstein: Hi, I’m Dan Rubinstein, and this is The Grand Tourist. I’ve been a design journalist for nearly 20 years, and this is my personalized guided tour to the worlds of fashion, art, architecture, food, and travel. All the elements of a well-lived life.

Before we get started, make sure to sign up for our new weekly newsletter, The Grand Tourist Curator, at either the link in my Instagram bio, @danrubinstein, or at thegrandtourist.net. You’ll get all the updates on the podcast, along with news and exclusive stories from the worlds of design, style, art, and more. Think of it as my own little personal cheat sheet, and we have a lot planned for this fall. Now, back to the show.

The art of cooking and fine dining is, to me, equal parts art, craft, design, and good old-fashioned business management. And I’ve always admired those who can elevate themselves to the very top of their game while also specializing in a particular segment of their field. My guest today has been elevated so much in food, he can’t really get any higher. And with his latest series of books, he’s helping the average podcast listener to elevate their game too. Eric Ripert. Many of you will know him as the chef of the famed New York seafood restaurant, Le Bernardin, the spot he became part-owner of at the tender age of 29, after the untimely death of his mentor. Or you might know him from his various TV appearances such as Top Chef, or as the traveling companion to my own personal hero, the late Anthony Bourdain. More on that later.

Like many of my guests from the world of food, he began cooking professionally at a very young age, and he cut his teeth working at La Tour d’Argent, a centuries old restaurant in Paris, followed by a stint working for the famously demanding Joel Robuchon. But Chef Ripert’s story begins with his upbringing in Andorra, the tiny principality stuck between France and Spain, where he learned a bit about living the good life through amazing food. I caught up with Eric Ripert from his offices at La Bernardin to discuss his youthful obsession with cooking, preparing dinner for Joel Robuchon’s dog, his latest cookbook, Seafood Simple, and what he thought of the recent horror satire film with Ralph Fiennes, “The Menu.”

(MUSICAL BREAK)

I wanted to start in the beginning. You were born in France, but you were raised mostly in Andorra, which is a place I think Americans know extremely little about. So, what was your life like there as a young man? What was it like to grow up in Andorra?

So, I was born in Antibes. My parents moved to Andorra, at least my mother moved to Andorra, when I was 9, and I stayed from 9 to 17 in Andorra, going to France from 15 to 17 to culinary school, and back at home on the weekend and vacations and so on. Andorra is a tiny country nested in the Pyrenees in between Toulouse and Barcelona, and it’s beautiful. At the time it was 30,000 people living there. Now it’s about 70,000 people. It’s not much.

Still small.

It’s like Monaco, but for the Spaniards and the French on that side of Europe, and it’s a lot of lakes and rivers and forests, five or six ski resorts, so you ski quite a bit, and you hike, and you do a lot of fishing in the lakes. It’s really a beautiful small country.

And what is the culinary or the food culture like in Andorra?

So Andorra, the official language is Catalan, then Spanish, then French. And for the food, it’s very much the same. The influence come from Catalonia, the region of Catalonia, then Spanish, and then French. Andorra itself doesn’t have too much food, because it’s high in the mountains. The weather is pretty rough in the winter, temperatures go down quite a bit, it’s a lot of snow. So you basically have potatoes in the winter, and not much else to eat. In the spring, you can go fishing, so you have fish, you can go hunting in the fall, but it’s not really much going on there. So, Andorra imports a lot of its food from, again, the region of Barcelona, which is very rich with vegetables and fruits.

And how did your family wind up moving there after? What was the purpose for that?

My mother wanted to go to Andorra because Andorra was very attractive at the time, because it’s a country that doesn’t have tax.

Okay. There’s all the reason you need.

So, she was a business woman that thought it was a good idea at the time. I was nine years old, so obviously I didn’t have really a choice. But we loved the country, and it was an adventure for me, because I had to speak Catalan, I had to learn the Catalan, I had to learn Spanish at a young age. Today, Catalan doesn’t help me much, but Spanish helps me a lot in the kitchen, as you can imagine.

Sure. Especially in New York.

And I speak French, and now English too.

And so I heard that you learned cooking from your mother, and that it made quite an impact on you. What was a typical dinner like at home?

So, I learned from my grandmothers as well, that were cooking soul food from their original countries. I had one Italian grandmother, one from Provence, so very rustic, very delicious, but not very refining presentations. Soul food. And my mother was very, very inspired by chefs from fine dining. And at the time we had Paul Bocuse that was famous in France, and Michel Guérard, and few other chefs that had a big name, at least in Europe. And breakfast, lunch, and dinner was an experience at home. We will change the tablewares, we will change the tablecloth, we will have different flower arrangements. And then breakfast was a lot of choices, including the omelet you like with the garnish that you wish or sliced ham or whatever you wanted. And then usually during the week I was eating at school, but on the weekend I will eat at the house, and it was appetizer, main course, cheese, dessert for lunch, and at night same thing, appetizer, main course, cheese, dessert. And they were never repeating themselves.

Wow. Sounds like a lot of planning for a family dinner.

It was a lot of planning. My mother was waking up at 4:00 or 5:00 in the morning to prepare all of that, because she was very busy with her business, and I thought was normal to eat like this. I really thought every child in the world was eating like me. I had no idea how lucky I was.

That is very lucky. And so, how did that inspire you? My next question was how you decided at 17 to go off to cooking school, but now it seems kind of clear, but did your parents approve? What was your family like when you said, “I want to go out of school,” at a somewhat early age to do that?

So, I wanted to be out of the school for sure, and I wanted to go to culinary school and learn the craftsmanship of cooking. I wanted to become the chef that I am today. Actually, from age four or five, I had this vision of being the chef that I am today, which is in a beautiful restaurant with a big team in the kitchen, all the equipment that is needed, and so on. And that vision was basically almost like an obsession. I had this really strong will to do that. And instead of studying, I was basically reading cookbooks at night when I was going home, so then my grades were very bad. And at 15 is when the principal said, “The grades are so bad, he has to find a vocation and do something.” And I was like, “Yeah, good. Now I can go to culinary school.” And that was the beginning.

And when you left school and you got your… Was it your first job at La Tour d’Argent? Is that the first one? Okay. So when you…

Well, I did a stage in between year one and year two, a two-month stage during the summer. That was very, very tough.

Like an internship.

Internship. I was 16 years old. The chef was very physical, very abusive, very scary, looked like an ogre. It was really, really tough. But I survived. And then my first real experience was La Tour d’Argent.

And can you explain to people, to Americans that don’t maybe perhaps know that restaurant, what that place was like when someone would walk in?

La Tour d’Argent?

Mm-hmm.

Yes. La Tour d’Argent at the time was a three-star Michelin restaurant. It was only 18 three-star Michelin in France. It was an institution, because in 1982 when I started there, they were celebrating their 500-year anniversary. That restaurant was a symbol of royalty, because the king was going to La Tour d’Argent. The restaurant was burned during the revolution, rebuilt a couple of times. I don’t know if you remember the movie “Babette’s Feast?”

Yes, I do.

So “Babette’s Feast,” the character, the lady who’s the chef, is actually the chef of the Café Anglais. And Café Anglais was La Tour d’Argent with a different name, and La Tour d’Argent kept on the side Café Anglais, but the iconic name is La Tour d’Argent. And it’s a building with six floors. The dining room is on the top floor, sixth floor, with the kitchen next to it. It’s a beautiful view of the Seine river and Notre-Dame de Paris. It’s a very, very special restaurant, beautiful. And a classic.

And when you started there as your first job, were you prepared for the working world of the realities of actually working in a kitchen?

When I started there, I thought because I had very good grades in school, I graduated, and I thought I was a good cook, I thought I will impress them with my age, 17 years old, and coming there and being a bright star. But it was the contrary. I walked in that kitchen, and I was the youngest by far, and my knowledge was very light to be in a kitchen of a three-star restaurant. And actually after three minutes I cut my finger, and I have to ask for a Band-Aid. And then they asked me to make an Hollandaise sauce, which became scrambled eggs, because I didn’t know really how to control the heat, and that was a failure. And then they asked me for chervil, and I didn’t know what chervil was. And at that point I realized I better put my head down and work really hard and try to be invisible and stay there.

How long did that process take for you to kind of…

It takes about six months to be comfortable and to understand the different tasks. Also, they were rotating us in a kitchen. We were a bunch of young guys, but they were all older than me. But it takes about six months to feel good, and then you change again and you change again, and you’re really never at ease, because it’s always challenging. After one year you can say, “This is my house, this is my kitchen.”

And then you famously went to Hamin, right?

Jamin.

Jamin. Sorry, I’m pronouncing it like it’s something else.

That’s quite fine.

Jamin, excuse me, under Joel Robuchon.

Yes.

What was that like? Because you wrote a memoir and you described this experience. How did you get that job, and why did that happen?

So, Jamin was the restaurant of Joel Robuchon. He was considered at the time the best chef in the world by basically all the European magazines, and he had three-star Michelin, and the restaurant was very tiny, 40 covers, 25 cooks in a kitchen working from 6:00 AM until 1:00 in the morning, you have basically five hours to go home, take a shower, sleep, take another shower, and come back. We were really working hard. That kitchen was very, very tough, very physical. We had no space. We were touching each other shoulders, because we were so many cooks, but it was needed for the food that he wanted. He was a genius in many ways, and his food was incredibly beautiful, but incredibly delicious at the same time. He was a very, very tough chef, because very demanding on himself, and therefore very demanding on his team.

The difference in between Joel Robuchon and the other chefs at the time in Europe, it was Joel Robuchon was not violent, physically he was not kicking you in the butt or punching you in the shoulders or throwing things at you, and he was not a screamer either, and other chefs in general were screaming at you all the time and insulting you. He was not like that. He was very different. But his words were really going to your heart like a knife.

Like for instance, I was very passionate about making sauce and I was in the fish station, which helped me much later on to be the right chef for Le Bernardin. But I was making sauce every day, and that was my job toward the end of my stay with him. And he will look at me and say, “Ripert, you have it or you don’t have it. You will never be a saucier.” And that will kill you. You will be like, “I work all the morning, I put all my love and effort in it, and he’s telling me that I’m a loser.” So he was finding, for everyone, it was a customized nice comment that will break your heart.

Was he someone that would tell you one bad thing and then one good thing, and keep you on the edge?

He was interesting, because he will start very softly to criticize you, and it will become more and more and more intense, and two hours later you will have forgotten your mistake, and suddenly he will become extremely intense and remind you the mistake you have done two hours before, and relentless and relentless and relentless. And then it will last for a week or two. So, a week later he will say, “And you remember what you did last Monday, when you gave me the red mullet or the striped bass undercooked, or overcooked? You remember that? How can you forget? You sabotage my kitchen.” And so it was really sticking to your skin forever.

Yeah. And I heard that you had to cook food for his dog, essentially. Like, dinner.

Not necessarily always me, but we were cooking food for his dog. He was a very hardworking man, he was taking a break to go have dinner with his family, he had children, and he will come back after his early dinner. And that was our break too. We will sit down and have basically half-hour to eat something. Very often we didn’t eat, we didn’t have time, but when we have time, we will sit and have dinner. And he will give us a call and say, “I can’t believe you cut the meat for the dog too big,” or, “It’s too small,” or, “I find some stones in my salad.” It was every day something. And at the end we were kind of joking, but it was not a joke, because it was pressure, all the time under pressure.

First of all, what kind of dog?

It was a very tiny poodle, I remember. And we basically didn’t dislike the dog, but I think sometimes the dog was not hungry. He didn’t want to eat the food. And Chef Robuchon was blaming us for the dog not eating. How can I tell you?

Did you ever contemplate giving up?

No. I had been very emotional many, many times. I was 17 when I started at La Tour d’Argent. I was 18, 19 at Robuchon. I was speaking to my mother every day on the phone when I was 17, and even when I was at Joel Robuchon. Every day I was explaining to her how hard it was. And she was very supportive, and she was saying, “Stay there, stay there. Stick to it. You’re good. You’re going to make it. You’re going to make it.” And I was like, “Yeah, I know I’m going to make it, but I have to tell you, it’s really rough.”

(SPONSOR BREAK)

And after that, there was a period where you went to D.C., and you worked at the Watergate Hotel. How did that happen? That’s a big step, to go from France to D.C.

Well, at Joel Robuchon I’d worked for one year, and then I was called to do my military duties, which were mandatory at the time. And I felt it was my luck to get out of that kitchen and take a break. But Joel Robuchon said, “I have connections and you can cook at the Elysée,” which is the equivalent of the White House, “for the team that cooks for the president of France.” And I thought, “No, no, no. I’m not going to do that, because he’s going to send me wherever he wants, and then I’m going to owe him, and I’m going to have to come back. I want to have options.” So I refuse. And I said, “No, I have to do my military duties where I am asked to do them.”

Then I came back a bit more than two years as the chef poissonnier, so responsible for the fish station. And at the end, I gave him six months’ notice. So by Christmas I said, “In June I would like to leave.” And in that time, you were waiting for the chef to tell you where to go. And he said to me, “Where do you want to go?” And I said, “I would love to go to Brazil.” And he said, “No, I am not sending you on vacation.” So then I said, “Well, maybe you can send me to Spain.” And he said, “But Andorra is almost Spain. Don’t do that.” So I said, “Well, send me anywhere you want. I don’t want to be in France.” And he said, “Why don’t you go to America?” And I said, “That doesn’t sound bad. Why not?” So he made some calls and I came to the U.S., started in Washington, D.C., not speaking a word of English, at Jean-Louis Palladin, which was in the Watergate Hotel.

And what year was that? That was ’90…

1989.

And I read that actually during this first trip you had to D.C., where you bought a copy of a book about Tibet, and that introduced you to Buddhism, and it was kind of an accidental impulse purchase. Tell me about that part of your life, because you’ve talked about how you’ve had issues with pressure and anger, and how this has really impacted your life. Is that still true today?

Oh, for sure. So, I find this book before I leave France at the last minute before embarking the flight. And I read the book, and I’m very interested. And then that year, the Dalai Lama got the Nobel Prize for Peace, and I read his speech of acceptance, and I was extremely, extremely touched and inspired by what he said. And then I asked my mother to send me some books in French, because obviously I didn’t read English. And I read his books, and I was like, “Oh my God, that makes so much sense for me.” The philosophy of Buddhism.

And I started to read and educate myself with a different vision. And Buddhism speaks to me at the time, and still today, and I went to his teachings, and then I went to different… When I say “his,” it’s His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Then I went to different masters’ teachings. And then it became for me a way to practice to be a more compassionate, a better person, practicing loving kindness as much as I can, and having a different vision of the world.

Buddhism is a philosophy, it’s a religion, and it’s a science at the same time that quantum physics really can explain a lot. And we’re not going to go into the quantum physics theory right now, but it’s something that changed my life for the better. But I do not try to convert the team. I find a secular way to bring what I learned that is positive to the team, and then we are all the same, all equal. It doesn’t matter where they come from and which religion they have, it doesn’t matter. But for me, Buddhism has been very, very important and very helpful.

Are you someone that meditates? Are you someone that has to take time to do that?

Yes. I wake up every morning, maybe around 6:00, before 6:00, and I meditate. I do rituals. I study. Once a week I have a teacher, he’s a monk, Tibetan [inaudible 00:24:33] he’s Nepalese, once a week we have a teaching together. And then I study quite a bit every day. So from 6:00 until 8:30, the house is basically sleeping, or 8:00, 8:30, I have time for myself to do that. And it’s very helpful to start my day like this. And then my family doesn’t really participate at all or shows interest in what I’m doing. And so I have my meditation room, and I’m happy, and I go to the meditation room, and they respect that very much, and we all live happily.

And what was the crowd there like in D.C.? It’s changed so much, and continues…

So, D.C. was extremely boring for a guy who was 24 years old at the time. I was like, “This is crazy. People don’t go out. At 2:00, it’s the last call. I’m leaving the kitchen at midnight. How can I have time to enjoy?” I was bored. And I was coming to New York a little bit on the weekends sometimes, and New York was booming and crazy. And in ’89, New York was really, really a good scene for young people. It’s still, I think today, a good scene for young people, but obviously it’s not my scene any longer.

But Washington was boring. I loved what I was doing with Jean-Louis Palladin. He was extremely creative, and his food was amazing. He was probably the first chef in America to create or invent the relationship between the farmer and the chefs. Farm to table, right? Nobody was doing that. But one afternoon, he will take his car and go to Maryland and get soft shells, and then he will go to Virginia and bring back hams and bacon, and then he will go to all the farmers and bring vegetables. And his food was absolutely amazing. And I was very, very impressed. My challenge was, I didn’t understand anything in that kitchen for quite some time. He was French, so I thought he…

How did you cope?

I thought he would speak to me in French, and he refused. He spoke to me in English only. And his frustration was obvious, because he will say to me, “Send. Send. Send the food. Send the food. What are you doing? Send the food.” And for me, I was like, “What is he saying? What does he want?” So it was tough, but he was a very kind man, and after the service we would laugh and joke, but during service was difficult, for sure.

And at that point you leave there and go to New York, essentially where you are and have been for quite some time, or was there a period in between before?

I left Washington. I had a visa, a student visa. So after my student visa, I went to David Bouley downtown in Tribeca as his sous-chef, because I knew David from Joel Robuchon, from Jamin. David came and was in training for a few weeks, and was in my station, so we became friends. And when he got four star in the New York Times in 1991, David called me and say, “Why don’t you come and help me? I really need some support, because we have four star, it’s a big deal.” And I stay with him a little bit. And then I had the opportunity to start at Le Bernardin as the chef de cuisine, under and Gilbert Le Coze and Maguy Le Coze, the brother and sister that owned the restaurant. And I’d stay with David about eight months, and then I came to Le Bernardin, and it was in June. And now we are 2023, so it’s 33 years, 34 years. 32 years, sorry.

And Gilbert and his sister had opened the restaurant in Paris first, I believe, and then it came to New York. What was he like? From what I’ve read that he’s been… He was a miracle worker with seafood. So, what did you learn from him in those early days, working shoulder to shoulder?

He was very interesting, because he was an autodidact. He never really trained with anyone except his father that had a restaurant during the summer in Brittany, to make a bit more money, because the father was a fisherman but it was difficult with the budgets. And Gilbert’s sister was in a dining room at age 13, 14, serving people, and he was helping his father. And then he never really got trained.

And they opened Le Bernardin in Paris in 1972, closed, came to New York in ’86, and I joined them in 91. And when he hired me, he hired me as the chef de cuisine. And he says to me, “Look, this is my style. This is what I do with the fish. I’m very, very particular about the freshness of the ingredients, especially the seafood. I go to the fish market every day for years and years and years at 4:00 AM, 3:00 AM. You don’t have to do that any longer. I taught them how to handle the fish the way we want them to do. And I want you to focus on keeping our philosophy, which is the fish is the star of the plate, and bringing your expertise from classic training in La Tour d’Argent, and working with Joel Robuchon, and the creativity of Jean-Louis Palladin, and I basically give you freedom to do whatever you want, and then I’ll support you 1,000%.” And from that day on, he let me succeed and make mistakes and succeed and make mistakes, always supported me. [inaudible 00:30:39] was amazing.

I mean, it sounds like from what we’ve said, that’s the first time you’ve probably ever heard that before.

Yes, for sure.

[inaudible 00:30:46] For someone to say, “Do it…”

Well, with David, I had a relationship that was very civilized, but Gilbert Le Coze was really like a mentor that was very nurturing, but without being fatherly. He was teaching me, but giving me a lot of freedom, and the safety net was him, he was still in the kitchen, but he wouldn’t intervene.

So for instance, I give you a quick example, but the captains didn’t want to write on the ticket the time when they will order the food. And I wanted them to say, “At 7:00, I’m taking the order,” so in the kitchen we will know we have 10 to 15 minutes to send the first course, and then we will monitor in the kitchen, also writing the time when the appetizer goes, and we will know more or less when the main course has to be sent. Captains were not accepting that at all, and I refused to take care of their tickets if the time was not on it. I said, “No, you don’t want to put the time on it? No food.” So the captains will go to Gilbert Le Coze and say, “The young kid is very rebellious, and he’s imposing on us things that we don’t want to do.” And Gilbert Le Coze said, “You have to deal with him. He’s my choice. He’s the chef. You don’t want to deal with him, you can go work somewhere else.”

Why did they refuse? It seems like such an obvious thing to…

I think for them was a cultural change. I was extremely young. I was the youngest of Le Bernardin of all employees. So in the kitchen, my challenge was to discipline that kitchen that was looking at the young kid, and they were like, “With this cute face, we’re going to kill him.” And they had no idea how well trained I was to take the pressure. And the waiters were the same. They were like, “Who is this kid coming here to tell us how to do? We are successful. We are already a four-star. We are in many magazines and in the newspapers everywhere. I know everybody’s speaking about Le Bernardin. We don’t take pressure from this kid, or we’re not going to listen to him. We’re going to actually kick him out.” And at one point I said, “Well, it’s going to be them or me.”

I mean, over seemingly… When you look back on it, it sounds really small, but also it probably made a mark in the sand, no?

Yeah. I was fearless. I had no problem at all to be extremely tough. Actually, I was way too tough. I was abusive, verbally abusive, and I was really making mistakes. I had to take a break at one point and realized that I was miserable, the team was miserable, and we were losing a lot of stuff, because my lack of diplomacy and understanding how to lead by example, and how to not infuriate the staff. So, that was for me a wake-up call. But Gilbert Le Coze let me go to the edge and make the mistakes, until I realized on my own that I was totally wrong. And then basically almost overnight I reversed my way of managing team.

And Gilbert died tragically very young, and you took over. Speaking about what you just described, did you have cold feet about taking over such a place in totality like that, at that age?

So I started in ’91, he passed away in the summer of ’94, three years later. And therefore I was already the chef under his supervision, but I was very comfortable managing that team. And Maguy Le Coze came back to Le Bernardin, she was very emotional, she lost her brother. I lost my mentor and a dear friend, and I was very emotional, and the team also was in shock. But I never questioned it. I went to her office, she called me, she said, “Will you like to stay with me, and we move forward?” And I said, “Absolutely. No question asked. I’m here. I’m not going anywhere.”

Amazing. And so what kind of legacy, I’m curious, you’ve touched upon this before, but if you could explain the legacy from Gilbert and the original Le Bernardin, even up to today, 30 plus years later, if someone could time travel and go to the first day it opened in New York, and then time travel and come here and have a meal today, would they still be able to draw a line, a connection between then and now?

For sure. The techniques I’m using are very different, because Gilbert didn’t master those techniques that I learned with, again, great chefs like Joel Robuchon for instance, or Jean-Louis Palladin, or the chef of La Tour d’Argent. I use also influence from my roots, which is Mediterranean, South of France, Andorra, which is Spanish influence. And then I travel quite a bit since I live in New York, I have been to Asia, I have been to South America, I have been to Scandinavia and many other countries. And my food, or our food, because it’s a teamwork today with the sous-chefs, is really inspired by experience, and that make the food very different in many ways.

But at the same time, we kept the same philosophy. The fish is the star of the plate. Fish is very delicate, texture-wise, flavor-wise. Few seconds, and your fish is overcooked. Few seconds, and your fish is not cooked. You have to be very delicate with what goes in a plate. You cannot overload the plate with garnishes and different sauce and so on, because you kill the delicacy of the species that you are cooking. And every species are very different from one to another. Tuna is different than halibut, halibut is not a codfish, codfish is not a lobster, as we know. And you have to treat them very carefully, and be a great technician.

So, that will be the common thread in between Gilbert and I. It will be that delicate legacy that we bring into the plate, to elevate the fish. Not caring so much about the presentation on the beginning, not caring about nutritional. I don’t care if you have starch and fibers. Of course I care later on in the process, but on the beginning, the only thing we care about is, how can we make this piece of halibut better? And after that, the exercise is reversed. We say, “Okay, we’re going to make it look good. And then what do we bring to be nutritional?” But on the beginning, it’s purely about flavors that enhance the halibut.

(SPONSOR BREAK)

And if a young chef comes to work with you in the kitchen, maybe they worked at any other one, two, three Michelin star restaurant, what is the number one thing you find yourself having to correct? To be like, “This is the way we do it here,” or, “This is our philosophy here.”

We have a lot of young talents that come to our kitchen with different experiences, and I ask them to be open-minded. And I’m not asking them to forget what they learn with other chefs, and some techniques are very universal. I’m just asking them to be understanding and respectful of what we do. And then if they play the game, we explain to them in detail along the way, when they evolve, we explain to them that everything has a reason. Nothing is just a gesture or technique just to show off. Everything has a meaning. We try to teach them, and we do that successfully, actually.

One thing I have to tell them right away is that they have to shave every day in our kitchen. Because for me… Or if they have a beard, they have to keep it very clean, clean cut, because the kitchen is an environment where you have to show immediate discipline on yourself, and cleanliness and so on. So if they have long hair, I don’t care, they can put a net, they can put of course a hat. They have to be clean on themselves, on their jackets, and their hands have to be clean, but they have to also show a certain discipline and make the effort to shave themselves every day, if they don’t want to keep a very clean short beard.

That’s great. And in this sort of post-pandemic era that we’re in, with all of the challenges that fine dining and all restaurants seem to go through, what is business like for you today, and the industry of running a major restaurant like Le Bernardin? What keeps you up at night that makes you say, “I got to really meditate this tomorrow”? What’s racing through your mind that is, if you could help people understand what’s important to you today?

Sure. Well, we have constant challenges every day in restaurants, as you can imagine. Lunch and dinner, it’s never the same, and you have to adapt very quickly. So by nature, we adapt, and I sleep pretty well at night. COVID was very, very tough, because we were closed, and then we were open at 25% capacity, and then it was at 50% capacity, then we closed again, and then we reopen. It was very difficult to find staff when we reopen. For some reason, a lot of the young people who are working in the restaurant industry left New York, went back to their states, find jobs in the different states, or went to their families. It was very, very difficult in 2021. Last year, 2022, we had basically a full team, because all the management came back at Le Bernardin, all the people with experience came back. So we had that plus for us.

And the clients came back, and clients were very eager to support the restaurants and the hospitality industry, so they were doing the best they could to come out as much as they could, spend as much money as they could, and that was really helpful at the time. So, 2022 was a fantastic year.

Now we are in 2023. We have really a great team. Of course we have challenges every day with some individuals, but that’s part of any company. Le Bernardin has about 170 employees. Today we are end of July, for lunch we were packed, full dining room. And then tonight we are really doing extremely well, we are packed as well. Very difficult to get a table, even in summer. The year is extraordinary for us. And I speak to a lot of my friends, a lot of them are very, very happy with 2023. And I see some people struggling, depending of where they are located, and depending of their clientele. But to my knowledge, it’s a minority. Most of everyone does really, really well. The biggest challenge we have is inflation, that has been really, really important in the country. But today it looks like it’s going back down, and that’s very helpful.

Has the client’s expectations changed?

Clients, when they came back to restaurants, were so happy that you could burn the fish, they will eat it and say thank you. But today, those days are over obviously, and they should be over. The clientele is very demanding, because they have very high expectations, and they should be demanding and have expectations, and we have no problem with that. It’s exactly like pre-COVID, when people were coming to have something special as an experience, and we are here to deliver that special moment and meal for the people that come here.

I have to ask you, because I’m just dying of curiosity. Did you see the movie, “The Menu?”

Yes, of course.

Okay. What did you think?

I mean, not of course, but yes, I saw it.

But yes. Okay. And what did you think?

I thought it was powerful in many ways, because it reminded me some bad memories from when I was in France, not in America, but in France. It’s like dark satire that makes fun of excess that have happened in many restaurants, that bring excess formality in experience, especially in fine dining, and a veneration of the chef that is not healthy. Chef is not God. Chef is your brother who has a responsibility of being a leader, and you shouldn’t have fear of the… You should have respect for the chef, but not fear of the chef. And if you’re a client, you have a voice, the chef is here to please you, and you are not enslaved by the chef. So “The Menu” is intense and is extreme, but it’s a mockery of what some restaurants have done, thinking they were creating fine dining.

Luxury, it’s not necessarily a place where you are, as a client, scared or intimidated or fear the reaction of the chef because you have an allergy, or you don’t like a certain ingredient, or you don’t want to follow the direction of the chef. It’s your experience. And we are here to cater for that. And fine dining should be fun for everybody. You’re coming to celebrate usually, or you’re coming to find an experience. People come at Le Bernardin to close a deal, to speak business, for romantic dates, for celebration, and you name it. And our job is to read your mind and to make sure we deliver this experience to you. And at the end, actually way before the end, you should be laughing, and you should be loud if you want to, and you should be having fun, and it’s the way it should be everywhere in restaurants. People should have a very pleasant experience, not an intimidating or boring experience.

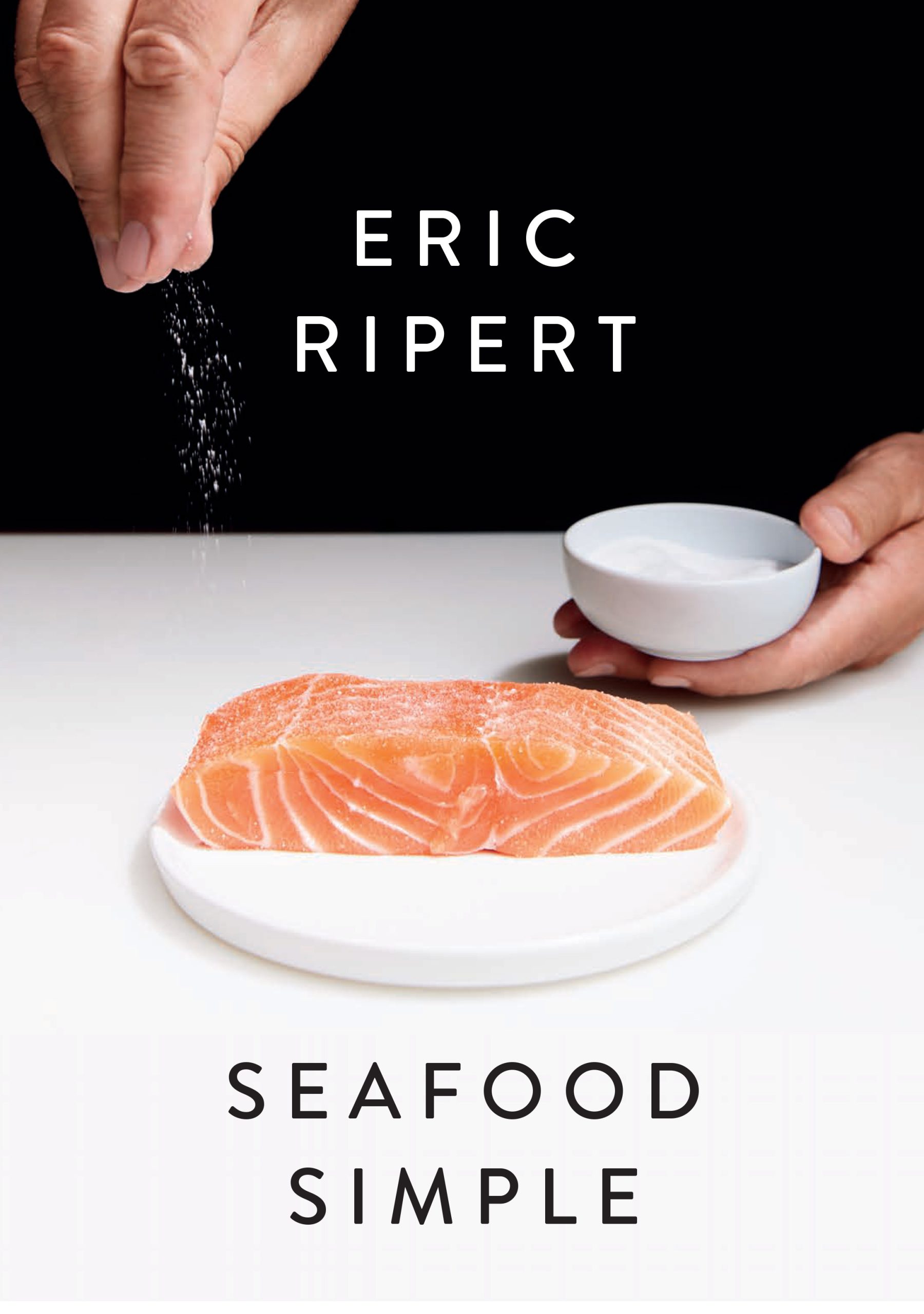

And you have this follow-up book called “Seafood Simple” coming out, which I think is a follow-up to your last book, “Vegetable Simple.” And what was the concept behind this new series, it may not have been a series at first, but why this type of book now? Why use this concept of focusing in on very basic and simple essentials, essentially?

So, “Vegetable Simple” was an exercise that was very different than “Seafood Simple,” in the sense that it’s no chapters, but it’s organic. You open the pages, and you start with snacks, and then you see soups and appetizers, and then it’s richer dishes, and finally some desserts with fruits which are not vegetables, but it’s basically plant-based. So that was a nice exercise that I liked to do at the time. I really wanted to pay homage to vegetables and fruits, and I thought, why not? It’s not because we have a seafood restaurant that we cannot do that.

And then “Seafood Simple” could sound like an oxymoron, because cooking seafood is not simple, except if you buy the book, of course. No, but to be serious, it’s interesting because I basically broke down the book in chapters that are following the different techniques that are appropriate for certain species. Like I said before, you don’t cook a lobster the way you cook a halibut, and you’re going to cook a halibut the way you cook a piece of tuna. So you have chapters for the major techniques which are grilling, broiling, steaming, sautéing, roasting, marinating, curing, and so on. And in those chapters we really, really show you in pictures and guide you through the text, second by second almost, and it’s like having me next to you basically, and you cannot make a mistake. It’s not possible. If you follow what is on the pages, you will have the result that you see on the page, which is the final picture of the dish.

And what would you say is the most common mistake you hear a layman make with fish?

Many mistakes. It starts by shopping. People do not know when fish is fresh and not fresh. And when they start to cook the fish at home, it stinks the house, and it’s very fishy and disgusting, and nobody wants to eat. So, people are intimated a little bit. And it’s few tricks, they are so basic, it’s not rocket science. So we’re showing you how to shop. And then a lot of people have the tendency to overcook the fish, and soon as you overcook the fish, it’s dry, it has no flavor, it’s not pleasant, you don’t know what you’re eating, and people say, “I don’t like seafood.”

So we’re showing you the tips again, which are very, very basic. Again, no rocket science here. And other mistakes is that very often you see too many things in a plate with the fish. So you see the fish, and you’re going to see some potatoes, and then you’re going to see some string beans, and then you’re going to see all the vegetables and mushrooms, and then you’re going to see a gravy, and you’re going to see… And then the fish disappear, and it’s like eating a plate of, I don’t know what, but not seafood.

And if someone were a layman and wanted to read this book, what is the first fish you would suggest someone start with, to really master?

It doesn’t really matter. What matter is the freshness of the fish. So, what is interesting is that you can choose any species that you like to eat, or like to cook for your guests, and then we take you by the hand, and we are together bringing you to success.

And there was an interview you did with The Harvard Crimson where you said that you loved cooking fish, and that you maybe were not as adept at doing things like pastries for example, because pastries are like a science, and cooking fish is about creativity, and there’s a sense of improvisation. And I’m wondering, what kind of advice would you give to those either working in a kitchen professionally, or just at home, really trying to make a four-course meal for their family. How do you improvise with cooking?

So cooking, if I can make an analogy, is like jazz. You can improvise quite a bit. And pastry, it’s extremely precise and scientific. And pastry, you have to follow the directions, and you have no freedom to get out of it, until you potentially become an excellent pastry chef after 20 years of experience in a restaurant, then you can break the rules. But you cannot break rules in pastry. In cooking, you can really, when you are comfortable with the basics, which we are teaching in Seafood Simple for instance, when you have mastered the basics, which are simple really, at the end of the day, you can really improvise a lot, and compensate. If it’s too much acidity, you can bring more richness in the dish, and then you can balance the sauce. And if it’s too much salt, you’re doomed. Good luck. So you have to be cautious. But except that, in cooking you can really improvise a lot, and depending of the season and depending of the quality of your ingredients, you can play and compensate and make something that is delicious, and also you can have consistency by taking a lot of those liberties.

And if you had a Sunday evening with your family, and didn’t have much time to prepare, what is a go-to Sunday meal for you like at home?

It all depends of the season. In the winter, for sure, we start with a soup, and very often I like to make a stew, but in the summer it’s much simpler. I probably will start with a salad and vegetables that I find inspiring and delicious, and then something light, probably seafood, or sometimes it’s purely vegetables. Sometimes we don’t even need meat protein, and I barely touch meat in the summer.

Really?

Yeah.

You’re not a barbecue person.

I am a barbecue person, but barbecue vegetables and fish.

And I have to ask you, one of my personal heroes is Anthony Bourdain, even though I’m not from the world of food necessarily, but from the world of writing and journalism. I was wondering, now that it’s been a while, is there a little fond story that you have that brings a smile to your face when you think about your time with him?

We spent quite some time together as friends, and also sometimes working together. And we even had a show that was called “Good & Evil,” and we went to 35 cities in the U.S., and we were sold out in every theater as well. I did a bit of TV with him. He was doing a lot of television, as you know. I did a little bit of comedy in theaters with him, and then we spent a lot of time together as dear friends.

We liked to prank each other. So, he will do things to me that will make me very uncomfortable at times. And then I will wait and have my revenge, because soon as he will walk into a car or walk into a plane, he will fall asleep, because he was always jet lag or traveling. And as soon as he will fall asleep, I will wait for him to open his mouth, and after saliva starting to fall on his shirt, and I will take a picture and post and say, “I’m learning transcendental meditation with Anthony Bourdain, the great master,” and put a picture of him like that. So, this is one of the many things we used to do together, pranking each other.

So in all of your experiences, I’m wondering, is there anything left that you’ve yet to master in your career?

I think I will study all my life, and because I’m Buddhist, I believe in many lives, which it’s convenient in many ways. So, I am going to study for quite some time, in this life and the other ones. It’s endless. The search for perfection is not perfection. The beauty is in a search.

(MUSICAL BREAK)

Thank you to Eric Ripert, Becca Parrish, and everyone at Le Bernardin for making this episode happen. The editor of The Grand Tourist is Stan Hall. To keep this going, don’t forget to visit our new website and sign up for our newsletter, The Grand Tourist Curator, at thegrandtourist.net, and follow me on Instagram @danrubinstein. And don’t forget to follow The Grand Tourist on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you like to listen, and leave us a rating or comment. Every little bit helps. Til next time!

(END OF TRANSCRIPT)

The newest gallery openings this week, including the dark side of the American dream, traditions of Aboriginal Australian painting, a cheeky photographer, and more.

For Italian fashion photographer Alessio Boni, New York was a gateway to his American dream, which altered his life forever. In a series of highly personal works, made with his own unique process, he explores an apocalyptic clash of cultures.

Plus, an exciting young British artist receives a retrospective, Marcel Dzama's whimsical drawings take a political turn in L.A., and more gallery openings.