Annie Leibovitz Shares Her Vision in Monaco

The newest gallery openings this week, including the dark side of the American dream, traditions of Aboriginal Australian painting, a cheeky photographer, and more.

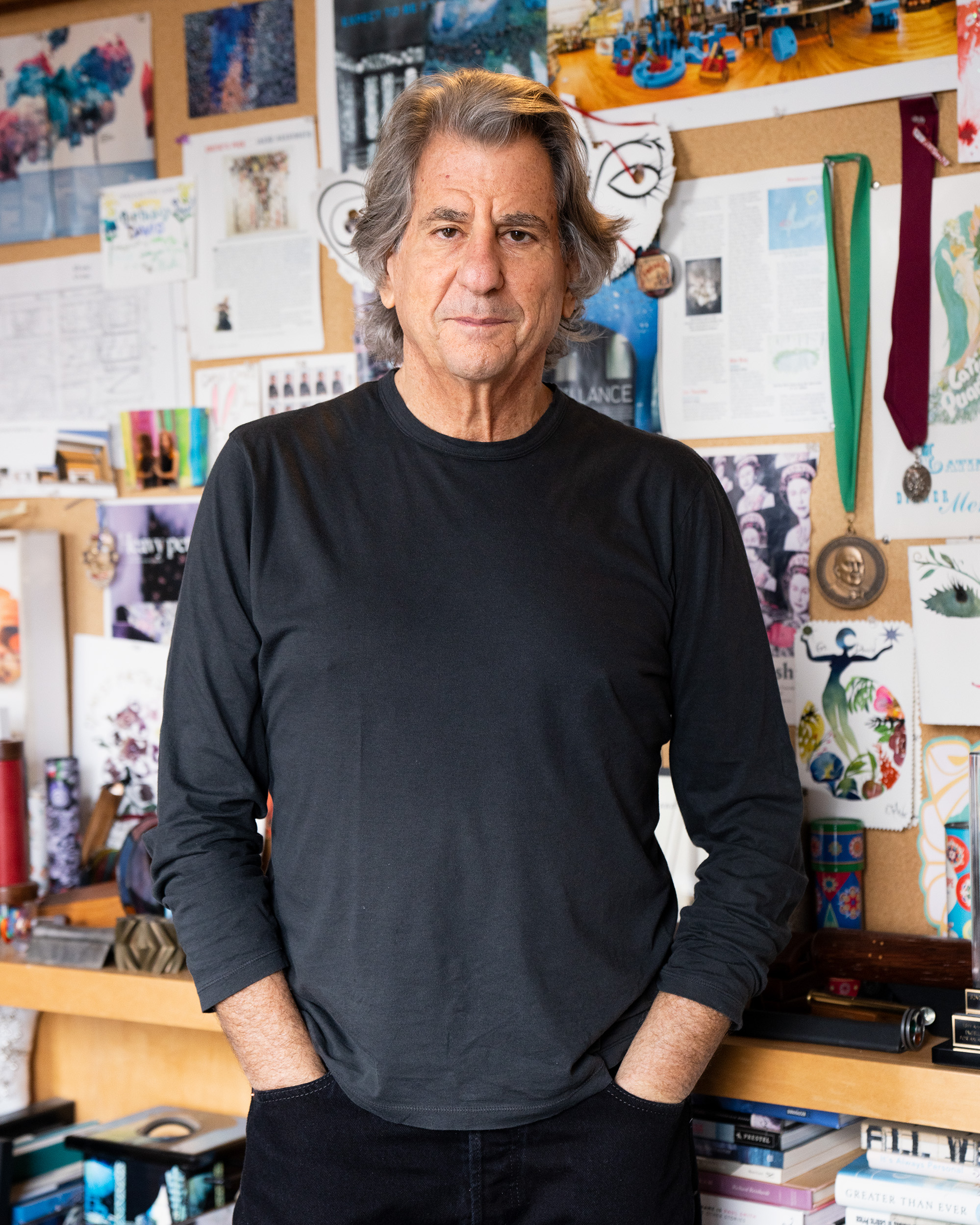

For four decades, this New York designer has changed the hotel game, turned restaurants into must-see destinations, impacted the daily life of cities, and brought a sense of style and ingenious spectacle to Broadway. On this episode, Dan speaks with the Tony Award–winning David Rockwell about his teenage years growing up in Mexico, some of his groundbreaking projects like the original Nobu, the state of American theater, the future of travel, and more.

TRANSCRIPT

David Rockwell: If I really knew what Chopin intended on the prelude, how would I play it? You study a piece and then when you play it, you have to sort of forget the practice and just play the music. And I think that is somehow relevant to how I think about designing is you do all the preparation, you do all the research, and then you have to create an idea, birth an idea that isn’t necessarily dictated by all those various pieces before it.

Dan Rubinstein: Hi, I’m Dan Rubinstein, and this is The Grand Tourist. I’ve been a design journalist for nearly 20 years, and this is my personalized guided tour to the worlds of fashion, art, architecture, food, and travel, all the elements of a well lived life. One of the beautiful things about covering architecture and design is how every studio brings their own unique talents and passions to a project. While many so-called celebrity designers might feign that they only do whatever their clients ask or try to explain about how their work is simply a matter of logic. Diversity in style, approach and outcome persists in the most beautiful way.

My guest today is someone who I can assuredly attest has made the built environment more comfortable, more enlightening, more technically advanced and more entertaining than most, and it’s probably the most unique mixture of qualities I’ve ever encountered. Through his hotels, train stations, airports, theaters, public works, products, restaurants, and more, he’s raised expectations on the power of design in so many ways. David Rockwell.

Born in the US and currently based in New York, David’s teenage years took an unexpected turn when his family moved to Mexico and his experiences during that time pushed him to become the creative powerhouse that he is today. And in 2024, David and his firm, the Rockwell Group, is hundreds of employees strong and is preparing to celebrate its 40th anniversary this winter. Nearly every major project of the Rockwell Group seems to have made an impact on its field. His early designs for the sushi restaurant, Nobu, became legend. His designs for some of the first W Hotels set a new standard for hospitality and the meaning of a hotel brand. And projects like the mixed use exhibition space and entertainment venue The Shed in New York expanded what was impossible with good design, and in his beloved New York, he was called upon during the pandemic by the city for a concept called DineOut, where clever planning by the firm help the town adapt restaurants to the outdoor world in one of the busiest and most demanding places in the world.

Of course, no discussion about David Rockwell will be complete without a mention of his work in the American theater. He maintains a studio that works consistently on Broadway productions. He’s won a Tony Award for “She Loves Me” and received six nominations for works on hits like “Kinky Boots,” “Hairspray,” and many more. And he’s even designed stage for the Academy Awards.

While all of these high profile and rather exuberant projects might lead you to believe that David himself is quite the attention-grabbing type, he’s anything but. Full disclosure, I’ve known the Rockwell team for years and even did some projects with them before my days at Departures. And as long as I’ve known him, David has consistently brought a sense of thoughtfulness and innovation to his field and his work for various charities is legendary. I caught up with David from his headquarters in New York while he nursed a cold to share his experiences as a teenager in Guadalajara, what Robert De Niro wanted from him when he built the first Nobu, his take on the American theater and more.

(MUSICAL BREAK)

I’ve known you for a long time and we have collaborated on stuff in the past, but I wanted to go back to the very beginning and I’ve read that you grew up in a theater family that casted you in repertory theater and so on. But I was wondering if did a young David Rockwell enjoy that at all or is that something that your family kind of forced you into like mine did with soccer lessons?

No, it was kind of the opposite of that. I was born in Chicago and moved when I was quite young, I think four, to the Jersey Shore. And my mom had been a dancer in vaudeville. I’m the youngest of five boys, so by the time I came around, of course she wasn’t doing that. But in this beautiful private suburb on the Jersey Shore, she helped to start a community theater. And as a young kid, I was instantly kind of mesmerized by how it transformed our little town. For those of you who know the movie “Waiting for Guffman,” it really isn’t that different. It was like a magnetic attraction to every part about it. I played piano as a kid, not well, but a lot. And every part of our community came together to make these shows. So, I was cast in some of the younger kid roles that were productions where adults played adults, but it was my first chance to, I think, get a sense of what became kind of one of the defining things of my career, which is how people working together kind of community attraction is what energizes places. It linked totally congruently to the other things I was interested, which was taking every piece of our backyard and boxes and making these low-tech Rube Goldberg contraptions.

What kind of contraptions?

We had a garage with a second floor. I made seasonal installations and I still try and get clients to do seasonal installation, so that hasn’t changed. My favorite thing to build was a spook house every year that used doors and rollers and buckets with pinging pong balls and lots of strings, very Rube Goldberg.

And what did your dad do? Your mom was in the theater. What was your dad doing?

Both my parents actually passed away at a pretty young age, and I think the kind of fleeting quality of their life and the amount of moving around that I did as a young kid really set me up to appreciate and yearn for moments of celebration and maybe an insight into temporal, which also became a big part of my work life.

My dad-dad died when I was three. My mom remarried when I was four, moved to the Jersey Shore with a man who raised me, John Rockwell, who was a businessman who also developed inventions and developed a fastener called the well nut. And at age 12, me, not him, he sold his business and had been researching highest quality of life and packed up the station wagon and my mom and my dad and one brother the other three were in college packed up and moved to Guadalajara, Mexico—

What was the well nut?

The well nut was a competitor to the molly bolt. The more well-known molly bolt, which you may be familiar with.

I’m not. Now you’ll have to explain.

It’s a fastener that goes into sheet rock and expands when it’s open.

Oh, okay. Well fitting. Oh, okay. Amazing. Who knew? Who knew? And so you kind of go from the Jersey Shore to Guadalajara almost feeling like it’s on a whim. I mean, was that kind of a culture shock for you as a young kid? How old were you at the time?

12. It was really a total positive, amazing transition for me. It wasn’t quite the same for everyone in my family, but I loved it. What was strange is how different Guadalajara was than Deal, New Jersey. Deal, New Jersey was this privileged suburb with big homes. Guadalajara was as if you took Deal and turned it inside out because all of kind of life happened on the street there. These beautiful rose-lined streets, soccer in the streets. So it was a great, great experience for me and I think influenced my work life and influenced how I think about color and materials and quality of light. It’s where I became fascinated with light and design.

And what did your family do in Guadalajara? Did any of them speak Spanish? Was there any friends there or was it just like a total cold plunge?

Cold plunge. But I went to a school called the American School of Guadalajara, which is about 40% English and about 60% Spanish. And I was totally fluent within about six months at that age. And I thought in Spanish as well. My dad had retired, but he did other little business ventures, different things he tried to do there. But what was interesting is he never really learned Spanish fluently, so I became the translator when he was trying to have these meetings, which was an interesting experience.

I think one of the things about Guadalajara that’s most powerful was my attraction to the marketplace and the kind of museum, the bull ring, the marketplace all coalesced in this kind of amazing public space, and it was a great gift. It was a great gift to be in a new environment. And I suppose my interest in reinvention and my interest in applying my skillset or my interest to a different building type certainly was influenced by that transition.

(SPONSOR BREAK)

And so after your life there, how did that lead to you going to Syracuse and sort of studying architecture there?

I would say non-linearly. I was interested in buildings and I was very interested in piano and I was curious about the kind of world around me, and I knew that whatever I did, I wanted to come back East. I had three brothers in the New York area. I knew I wanted to be around the theater in New York, and so I mostly focused on East Coast schools. And my portfolio submission for Syracuse University was playing a Liszt rhapsody and some drawings.

But it was not a predestined Frank Lloyd Wright I got blocks as a young kid and that’s all I was going to do. It was a hunch that it was an interesting thing. It was certainly based on starting to look at forms in Guadalajara and visiting Syracuse, liking the campus, and then being enrolled in the architecture program, which ended up being a great experience. But it was a little bumpy at first.

And I’m curious, what year was this when we’re talking about going to Syracuse?

’74.

So, the architecture education back then, was it… Take me back.

Strict modernist, strict modernist. It was Werner Seligmann was the dean, so it was a pretty strict modernist school. I had no idea about that when I went there, and I remember I came from Mexico driving directly with my Mexican huarache on and showed up and our first assignment was to draw something on the campus. We were given a sketch pad. And so I went out there and Hendricks Chapel was in the distance, a beautiful building, and I put one of my Mexican sandals at the base of a tree and did what I thought was a kind of simple, beautiful drawing of the landscape. I looked to my right and person, his name is Jeff Hill, if he’s listening, had drawn what was like an M.C. Escher drawing of the entire campus. It was really intimidating.

And then that evening we were invited to Hendricks Chapel to hear Buckminster Fuller speak. I’m not sure how many people there would’ve admitted how little they understood of what he talked about, but it was just such a kind of over my head conversation and that together with the culture shock of being from Mexico, I went to see my basic design professor the next day and said, I think this may be a mistake. I may have made a career mistake. And he looked at my drawing, we talked a little bit and he said, why don’t you stick with it? It’s possible you have a little less to unlearn than other people, but coming in fresh and being curious and learning may be a good way in, so why don’t you stick with it? And I did. And he was very supportive of an approach that was interesting to me that was, I think in conflict a little bit with a kind of strict Bauhaus training, was I was always interested in narrative.

So if we were given a figure ground project to create a two-story figure ground out of foam core, I would write a backstory or narrative about what evolved to lead to that. I’ve got to say, while it wasn’t totally embraced, it was tolerated and ultimately it became something that I had really interesting conversations with people about. And I was fortunate that I held on to the kind of rough edges of what interested me and didn’t feel the need to kind of totally conform to what the kind of stated model was. But it was a challenging experience early on.

And I know you started your own studio around ’84 I know you started your own studio around ’84, if I’m remembering correctly. And after Syracuse and before ’84, what were those years like?

I had taken some time off from school after coming back from London, studying at the AA. It was a program abroad. Got a job working as a assistant for a lighting designer on Broadway named Roger Morgan. Amazing man. And he was also a theater consultant, so he needed a drafts-person, so I would draft details in the day and be around the theater in the evening, I went back to school and finished my training. It was a five-year program. By ‘79, in my mind, I was really out of Syracuse in New York and looking for things to do, and I worked for a number of different people. Ken Walker, who is a really interesting architect designer. I worked for a guy named John Stork, who is still and was then one of the leading recording studio designers in the world. That was his specialty. But because he was focused on recording studios, projects that were on the edges, which I would say is where I like to live my life as projects that merge different pieces, he was less involved with, so it gave me a chance to be more involved. So I did one or two projects as Project Lead with John Stork. One of them was… Are you familiar with the Crazy Horse Saloon?

Somewhat. I know of it.

It’s a legendary club in Paris. It’s a cabaret with projections on beautiful people, and it’s a legendary place that was coming to New York. And they approached him, he approached me, so we did the room for that. An opening night, I was approached by someone asking if I would do their restaurant. So that was really the beginning of me jumping off, was thinking about doing this restaurant on my own, which was Sushi Zen and had a long run, like a 22-year run. And Sushi Zen unexpectedly won lots of awards and got a lot of recognition and kind of launched me in the world of hospitality.

Why do you think Sushi Zen was so successful critically at the time? What were you doing differently that was a light bulb moment for people, or what was different?

I think one of the things that was different that is still something that’s incredibly meaningful to me is designing from the experience out. We really looked at movement. The main partie was movement and choreography. So it was a narrow, I believe, 25 foot wide shoebox with no natural light on 46th Street. There were round glass rondelles set on the floor, that created a kind of runway that led to a sushi bar that was basically lightning bolt shaped. So it took a kind of rigor of one line and broke it into a number of places where you could gather around the sushi bar, so it made it more social. I worked with Donna Granata, who was a costume designer at the Santa Fe Opera Festival. And the two side walls were silk murals without 100 different colors of silk layered. And it was life and death for me. I mean, I think that sense of getting every detail right is life or death is…

Were you just really invested in it, financially invested?

[INAUDIBLE].

Okay.

Well, not only was I… I actually borrowed money from a friend to lend them money to do the edge lighting for Neon because they didn’t have the money to do it. I think it was luck. It was good timing. It was very different than anything that had come before it. And the sushi chef was extraordinary, so it became a kind of great place. Nothing makes design look better than good food.

(SPONSOR BREAK)

I’m curious, when you graduate and you’re starting this new, you talked about some theater work and… What were your ambitions when you started your firm? Were you like, “Oh, I’m going to do these restaurants and then I’m going to somehow get into… That’ll be my day job and then I’ll do some theater?” What was in your head at the time? What were your ambitions?

I would say my drive to create. I was voracious. I was curious about everything around me. I was madly in love with New York City, and I just saw it as a great laboratory for trying different things. So there was no strategic plan at all. And I do think when I’m speaking to young designers who are starting out or people who are working here, one piece of advice I give them, which I did not take myself, is don’t put every idea you have into your first project. But Sushi Zen was a case where I just loaded layer upon layer of thinking about movement and what makes a great place. And lighting has always been an obsession of mine. So one thing I say is don’t put every idea you have into your first project.

And the other is don’t try and think out strategically what your career is going to be, because I think that just eliminates options. So there was no focus on day job, night job. I was grateful. I took every design opportunity I could, and I really thought it was survival to make these places great. What I guess is the creative instinct to, and in some ways my history before that, transitioning from place to place in early losses and seeing how design brings people together was a kind of mission for me that led to many restaurants. And I have to say, I had no real insight to restaurants. I’d been to a New York City restaurant. I was 11 before we went to Guadalajara, which made a big impact on me, called Schrafft’s. And in Mexico, I really totally fell in love with, as I said, marketplaces, but also these little hole-in-the-wall restaurants that were pop-up places, maybe Saturday and Sunday where they only served one dish, which was really kind of an extension of how people lived. So I think all that became kind of part of my fuel.

And I was very lucky, as I said before about Syracuse, to keep the things that I was interested alive. And that led to many, many restaurants, some of them built by scenic shops. I designed a renovation for La Parador. Design and construction was six weeks. And the scenic shop from La MaMa, built it. So there was no project too small or too big. I was just… And that still is largely true for us. How we pick projects has very little to do with size and has to do with, do I perceive there’s open space? Is there a client I want to engage with? Is there a building type I haven’t done that continues to intersect things we’re interested in my studio.

And at what point did you begin your sort of could say career-spanning collaboration with Nobu with that first restaurant at Tribeca? How many years after Sushi Zen did that happen?

That was about nine years after Sushi Zen. After Sushi Zen, we had done a number of restaurants, mostly New York, but some of them around the country. There were a number of things that happened pre-Nobu. One was we did Vong for Jean-Georges Vongerichten, which was his first restaurant in New York, other than… He was a chef at Lafayette. When he left being the chef as an owner. And that was just such a thrilling, immersive, amazing… I mean, he’s such a genius, and it’s where I kind of learned how to extract, to find a point of view that couldn’t exist for any other person than him. So with the restaurant, it was a kind of portrait of observations about the food and the chef. And then we did Monkey Bar.

And Nobu came about because I was designing an event for Citymeals on Wheels—

Famous charity in New York.

Famous charity in New York that I’ve been on the board on for more than 20 years. This was an event at the South Street Seaport called the Feast of the Many Moons. The Feast of the many Moons was the great Asian chefs from around the world coming to New York. I guess it must’ve been ’92 because Nobu opened in ’94. And I was on a ladder, lashing backlit moons that would glow, and got down off the ladder and I got to taste some of the food. And I tasted Nobu’s rock shrimp with the ponzu sauce, and it was amazing. And I said to him, if you ever come to New York, I would love to work with you. So I met with Drew Nieporent, who was the restaurateur partner. I met with Robert De Niro, who was also a partner. And they gave me that opportunity to do that restaurant in Tribeca.

And I had no sense of how significant that was going to be. And I guess that’s a through line about your question, was there some strategy? I think having a strategy rules out all the things that happen on the way. And I think one of the things I’ve learned about a restaurant and theater, just the different paradigms, is there’s a lot of preparation that goes into your spontaneous experience. There’s months of rehearsal for a two and a half hour show that’s totally bespoke and will never happen again that way. And in a restaurant, all the work goes into that meal that’s presented to you.

So with Nobu, I knew I loved his food. I had no idea what a cultural phenomenon was going to be, which is probably a good thing because it may have made us a little bit more self-conscious about decisions we made. And I ate his food, I got to know him. I got to understand what Bob de Niro’s concerns were, Drew Nieporent, who was really operating it.

What was that first sit down meeting with Robert De Niro like? When I’m sitting around the table with a bunch of you, why was he doing it? What was he telling you he wanted?

Well, he discovered Matsuhisa from LA in a restaurant called Matsuhisa, which is still there. So I think it was his idea to bring it to New York. Tribeca Grill was already open, I believe. So he had this experience of helping to build a neighborhood which he cared about in Tribeca, and he, I guess, enjoyed the restaurateur aspect of producing. It’s not that different from producing a movie or a play.

When I met with Nobu, who was the first person I spoke to, I got a sense of the uniqueness of his combination of Japanese rigor and South American flavors. And that was an aha moment for me of realizing we didn’t want to trigger the same visual cues of every Japanese restaurant, but wanted to bring in this kind of Peruvian hotness of color and wanted to have a place that engaged all of your senses. So the scorched ash tabletop, as an example, was all of the design features. When they got to the table, for a three-star restaurant, there was no tablecloth. There was a simple wood plank that actually felt good to touch, that engaged your sense of touch.

So there were a whole number of things. And we did really an insane amount of research and backstory about Japanese landscape, because he was not from the city, he was from the country, which led to the abstracted trees.

The first meeting with Bob, who’s really an amazingly smart thinker and really deeply interested in design, and we’ve done a lot of projects for him, including the Greenwich Hotel in Tribeca, which is a ground-up building that he built post-9/11. The first meeting was really him talking about entrance, how people entered the space. I talked a little bit about wanting the sushi bar to be kind of a kabuki-like simple wall with a kitchen behind it, which was slightly unusual for a Japanese restaurant to combine sushi with the kitchen because so many of their dishes go back and forth. And he was very respectful and listened to what I had to say, made some suggestions. We talked about flexibility. And I’ve got to say, Drew Nieporent, who’s an amazing guy really pushed for total flexibility, and I pushed back because I think a dining room actually needs to have parts that aren’t flexible I think, banquets, booths, things that you can’t clear to just have the room be totally flexible. But it was the beginning of a long, long relationship where we’ve done, I think 25, a long, long relationship where we’ve done, I think 25 restaurants with them and in many hotels. And it’s a privilege to have long-term relationships as an architect. It’s something you don’t get to do very often where you get to iterate and change and revise and rethink.

And I guess fast forwarding a little bit, if you met somebody at a dinner party and you had to explain to them what the Rockwell group was just sitting next to someone in between courses and they asked you, “What’s the Rockwell group?” How would you respond?

Oh God, that’s such a hard question. Probably what I would say is we’re architects and designers. But as we got into it I would … It’s a very hard question to ask. I think you sort of have to get into a dialogue, but I would say architects and designers. Because I think set design, production design, all of that really grows under the design world. And actually, as I think about it, I think some of the most profound experiences I’ve had or where we’re doing more than one role where we’re creating the building and the content. There’s been, I think three theaters where we’ve designed the theaters and the opening shows in those theaters. And we’re now working on the Perlman Center downtown that opens in September. We’re doing the public spaces and we’re also designing the opening show there. It’s a little bit like setting the ground rules and then getting a chance to work within those.

Dan Rubinstein:

And when it comes to the theater work today, can you describe, first of all, how did you wind up really starting to do that for Broadway and what that big break was? And I know that eventually you got a Tony and then it seems like it was just a downhill from there on in. If you could explain a little-

It’s always uphill.

It’s always uphill.

I don’t know if that’s true in what you do, but that sense of life and death that I felt [INAUDIBLE] is still very much part of our DNA. I think every decision matters, and I think really embracing that sense of possibility. Let me answer the question this way. I think if you would say, “How did Nobu happen?” It wasn’t a quick thing. It was years of doing restaurants, years of doing work for Citymeals on Wheels, and then an opportunity that turned into a project. Union Square Cafe, I knew Danny 15 years before we did the new Union Square Cafe. I was a client, I was a friend, we had a dialogue. I think we’re living in a world where people expect things to happen instantly and we get entertainment in 30 second bites or less. I think we look at things over a long period of time.

And theater happened over many years. I had always been interested in theater. I was always sketching in the theater. I had lots of friends who worked in the theater, including Jules Fisher. I don’t know if you know Jules, but he’s the preeminent lighting designer in the history of Broadway. He’s really a legend and an amazing guy, and a friend I made when I was 19 in architecture school. When I was researching a project, I reached out to him and we stayed friends over all those many years. We went to the theater together. And over time, when I would critique sets of a show I saw, he finally said, “Well, if you have so much to say about it, why aren’t you doing that?” And I said, “Well, I have a very busy studio and I’m not sure how I would even make that transition.” And he said, “Why don’t you just start to meet people?”

It was a four or five year process of meeting with directors, sketching, listening, and trying to figure out what was my way in, what was our language and how would that match with how directors want to work? And ultimately, the first breakthrough was me understanding that what I find most thrilling about design is how it sets the stage for the story. I’m interested in movement, I’m interested in change. I thought about the Rube Goldberg contraptions, my interest in things that transform, my interest in technology. We started a small technology lab called the Lab at Rockwell Group based on trying to study these things. And then there were several false starts that were heartbreaking. And then ironically, I almost turned down the first project we were offered, which was in ‘99. I had done work for many non-for-profit theater pieces. This was the first Broadway opportunity.

And again, I think not knowing how significant it is helps deescalate the anxiety about making any decision. But it was the Rocky Horror Show directed by Chris Ashley, who’s an amazing director, produced by Jordan Roth, Jordan’s first show. And having lived in Mexico from 12 to 18, somehow that slice of American popular culture didn’t exist for me. I didn’t really know about the movie. I got the DVD and watched it, and I came back in and said, “I’m confused about this. Just why?” Because I was thinking theater was going to be like the Cherry Orchard at BAM. I thought it was going to be the more academic partner to my more populous day job.

And so the Rocky Horror Show on Broadway … But Chris Ashley, who’s really such a brilliant guy now runs La Jolla, said, “In some ways you have to see it with an audience because the Rocky Horror Show is about self-creation and it’s about an audience participation.” And it was a brilliant thing to say, and it was an amazing first project. And I go back to Siegfried Snyder saying, “You have less things to unlearn.” No one had told me you couldn’t have the floor rotate and turn around and go into the floor. I was able to do that. I think not being in a hurry, being willing to take creative risks, trying to figure out what is your unique point of view into a project is the driver for us.

(SPONSOR BREAK)

And you’re now reaching this milestone of 40 years of the firm, and I would say that you still see yourself as a booster of design and architecture as an industry for good, and obviously you’re also involved with lots of charities and things like that. Do you think that today things like sustainability and artificial intelligence and design, is it making it harder for design professionals to actually make an impact on the world, or is it more important and easier than ever or harder than ever? I’m wondering what the internal monologue of a lot of architects and designers are today, because it seems like a lot of them are stressed in a way, or they feel like there are a lot of obstacles now to realizing a vision.

Well, that’s a multi-layered essay question. The work we’re doing now is work that I’ve been curious about for 10 years. It’s happening now. The work we’re doing for Johns Hopkins at 555 Pennsylvania Avenue where it’s very similar to thinking about how movement, how choreography, why people want to be together in the same place, what creates a magnetic place? Because a university has the same challenges of professors and students don’t want to show up in person. They’ve had the Zoom experience.

And so what do you create that physically attracts people to be together? And I think that’s why I was interested in the city as a place, why the community theater as a kid. And we’re doing more and more of that. We’re redoing the Union Square W, which was I think the second W, and a total gut redo in the Guardian Life building, and that’s a chance to take a crack at something we did 20 years ago and redo. I think we are boosters of design as a discipline because I think more and more, architects and designers are finding that having a seat at the table of how things work is critical. The questions of AI … and what was the other question?

Sustainability, all the modern issues that people have to deal with today. Is that making—

Well sustainability is no longer a non option. I think anyone who’s not looking at sustainability as a cornerstone of their business does not have a sustainable business. I think that ship has sailed and I’m really glad it’s sailed. It does mean there’s a whole set of other things people are talking about like, not just leads, but also, “Well, what are the elements that lead to emotional wellness in a space and criteria for that?” And so I think sustainability is always something to learn more about, but I think it’s what is absolutely required for any designer operating in the world and we take it very seriously. AI is an interesting question because I think there are some industries at the moment who are very concerned about that replacing the work they’re doing, particularly in the writer community. And I have lots of friends who are writers and talking about that.

What we’re trying to do with AI at Rockwell Group is use it to build a model of knowing all of our work so that it means there’s a faster initial iteration, but it’s still going to be driven by having, in our case, a non-linear point of view. A friend of mine who’s a writer said, “The one thing AI can’t do is comedy because it can’t understand that irony.” And I think probably the same is true for you can look at juxtapositions in the world and ask that to come up with one, but I think we’re doubling down on craft in making and the opposite of what AI would do to build a handmade world. But we are using and understanding how AI can be a tool for delving in a quick sketch way into something you’re curious about.

And today, your theater part of your business, how many designers work in this specialized studio?

There’s two full-time set designers and me. It’s a smaller group, and two or three freelance people per project. But every other part of my business is permeable. Between our studio in LA, in Madrid and New York, there were about 350 people and those are divided into 10 different teams in New York that do a lot of different kinds of things. But theater is a specialty that it’s me and these two great people and then a number of freelance people we bring in per project. And the LAB is about 20 people of that 350, and that’s made up of strategists and technologists and sculptors and painters.

And so I’m curious, do you just go to the theater yourself, even if it’s not a client? Do you just enjoy going here in New York, being here so close to Broadway?

I do. I think there’s many things that are miraculous about New York. There are things that are challenging, but the 41 Broadway theaters, the fact that these are these precious resources that have stayed alive and very much about collaboration. Somebody to think about that always amazes me and with the first Broadway show I saw was Fiddler on the Roof. But I think it’s a great paradigm to create one memorable moment, there’s probably 25 people who touch that moment, writers, choreographers, tech directors, lighting designers, everyone else. I’m leaving off actors. And I think that holds true in the built world as well. I go to the theater. I’m now on the board of the American Theater Wing. I’m a Tony voter, so I go see everything. But I saw—And so, I’m a Tony voter, so I go see everything, but I saw everything before too.

Okay, so if you’re a Tony voter and you see everything, I’m curious, just like the film industry is going through, it’s different kind of crisis right now with the writer strike and now the actor strike, and people talk about theater and how it’s changing and how hard it is for works to be successful and to really survive. What is your take on the whole situation of the health of American theater?

I don’t know the answer to that. I know what my answer would’ve been a few years ago. I think it’s challenging right now. My overarching answer is everyone’s always predicting the theater is an invalid and not going to survive, right? That’s a thing people say every 10 years, and it does survive, just like people who feel like the city is at this crisis point right now. And it’s a challenging place, but you look at how the city invites action and allows participation and reinvention, like who would ever think that an abandoned rail yard would be one of the great parks?

Or that the waterfront that was mostly for cargo coming in is now this necklace of parks around the city. So, I think theater will survive. I think it’s in a challenging place right now, economically there’s a lot of shows that are suffering and hurting, and I don’t think the full population of visitors to New York is supporting the theater quite the way they have been. But I think it’s temporal and I think the solution is doing great work and trying to not spend money you don’t need to spend and trying to have a very specific point of view.

We spoke a bit during the pandemic for a story and departures about travel and what we thought maybe the future was going to bring. And I’m curious now that you have a greater pulse on things in terms of travel and entertainment and performative works and public works, and you have your Playground project, and what is your prognosis now? Have things changed or not changed in the pace that you thought that they would maybe in the depths of lockdown a couple years ago since we spoke last?

Well, I went back and looked at that conversation.

Oh, okay.

And they haven’t changed as much as I suggested they would, but I’m still hopeful. I think there are a few industries that you can identify that seem as broken is travel by plane. It’s just so fraught with so many challenges. It’s one of the reasons why for many, many years I said I wanted to do an airport and we had a chance to do the JetBlue terminal. I brought in a choreographer, which JetBlue thought was just semantics, but it was not at all. It was to deal with how to have movement that feels intuitive. But when we talked, I suggested there was going to be this interesting emergence of, or combination of luxury and non-luxury that there would be more privacy at airports. That the pandemic and the need for flexibility, which I still believe is architects is the biggest lesson from the pandemic, is to lean into flexibility and changeability.

But I think the airline industry has been slow to adapt to that. We did design the experience and the trains and the stations for Brightline, which is the train connection through all of Florida, and now is expanding to LA to Las Vegas. I think that’s an example where there’s been a kind of merger of popularly priced, but still some elements of luxury and privacy. And I think that’s the interesting thing about travel is there’s the luxury travel for the 1% is fine, but it’s everything in between that I think is still open for some reinvention.

I took the Brightline, I think I took the Brightline once and it was actually a great experience.

Fantastic.

So, in terms of we’re speaking about hotels and travel, today if I came to you and said, David, I’d love for you to teach a class at Syracuse about designing hotels, what would you tell your class? What makes a good hotel?

What’s so interesting about the question is one of the things that makes a great hotel is an environment that doesn’t call attention to the physicality of it. When you think about how do you get from place to place, how are the building systems in the room, what is the lighting like that you can control by the… So, I think there’s obstacles to making a frictionless hotel experience that involves not calling attention to the physicality of it. I think the other thing that makes a great hotel is a point of view where that hotel couldn’t exist in any other place other than where it is.

I was in Milan for the furniture fair this year, and the Four Seasons in Milan, of course there’s Four Seasons all over the world, but that particular hotel is so linked to the quality of the courtyard, the quality of the rooms, the idiosyncratic nature of every room being different. So, I think having a strong point of view that links to its location, not having the physicality create a lot of obstacles, and having some places that trigger intense memories that both are about the place and its location. I think those are the building blocks of a great hotel. And then there there’d be subclasses, there’d be a class on lighting, there’d be a class on acoustics, there’d be a class on textures, how things feel.

What would you say is the most under-appreciated element of all of those things in terms of hotel design?

No question, I think acoustical isolation of the rooms and mechanical systems. Draft over the bed, I think there’s things that deal with environmental comfort that are overlooked by most consumers that have a bigger effect on their experience. We did design the first Equinox Hotel at Hudson Yards, and I’m happy to say it’s a big success. And part of it was drilling down on what their point of view was going to be, which became a great place to sleep. Once you start to look at what creates a great place to sleep, it allows you to drive into doing things that other hotels don’t do. But a lot of those are invisible, they have to do with the building systems and blackout shades.

And things like that. Yeah, I mean, especially for Equinox, where I guess they’re expecting everyone to be going to the gym and really needing their proper eight hours of sleep or whatever they’re getting.

Kind of although what their mission was, it’s not linked to the club you can get from the hotel to the club, but they were looking for a new form of luxury, which really resonates for me. I think Nobu in 94 was one of the reasons it was so successful is that interpreted luxury is maybe the meal isn’t two and a half hours, maybe the meal’s an hour and a half and you get an hour back to do other things. And maybe luxury is food arriving as it’s cooked, not all at the same time, and just a number of things that I think luxury is always in transition.

And what’s next for your firm? I mean, obviously that’s something I ask a lot of people. You have a big firm, there’s a lot coming up. Is there anything in particular that you’re kind of most excited about?

Yeah, I’m very excited about the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg Center at 555 Pennsylvania Avenue, because I think it’s a very unique project and it’s a place that will be about its graduate level. All their colleges at the graduate level will participate in this research education building where the idea of cross-pollination of ideas is the fabric of the building. So, it’s a different scale. It’s an amazing opportunity and we’ve had a chance to work with awesome people there. So, that’s one. I’m excited about a small project we’re doing for Simon Kim, who owns a restaurant called COTE, and we’re doing a restaurant for him called CoqoDaq. That’s in very simple, but it goes back to some of the ideas I thought were relevant at Sushi Zen of illumination and path. Oh, we’re doing a teeny project at New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center called, I’m not sure I get the name right, the Harvey Fierstein Theatre Lab.

So, it’s a small, flexible theater space that ties into the library for the performing arts, amazing archive of material and creates a place where you can workshop something new, you can interact. It’s a physical place to interact with their incredible library. And that opens in the fall, or probably opens in the spring. It’ll be done in the fall, but then they’re going to have to get the bugs out. I mentioned Union Square W. Those are the things. Oh, well, I can’t talk about that. There’s several projects I can’t talk about that I’m very interested in.

What’s the next Broadway show you’re working on or any?

Well, the next theatrical thing I’m doing is the two weeks of opening events at the Perelman Performing Arts Center, which is interesting because it’s a thing. It’s a environment that has to work for two different weeks of things. And then I’m doing a Broadway revival of a play called Doubt, written by John Patrick Shanley. That was a play I loved working with a director. I love Scott Ellis. And in Chicago in November, I’m doing a musical with Jerry Mitchell, who I’ve done seven or eight shows with, who’s a great partner called “Boop!,” that may hopefully Betty Boop was an incredible creation growing out of The Depression, and it’s going to be an interesting, fun, big, bold musical.

Wow. I never thought that I would end an interview on Betty Boop, but I can’t really top that. So, thank you so much.

There’s no topping the Boop.

There’s no topping the Boop.

Thank you to our guest, David Rockwell, and to Joan MacKeith for making this episode happen. The editor of The Grand Tourist is Stan Hall. To keep this going don’t forget to visit our new website and sign up for our newsletter, The Grand Tourist Curator at thegrandtourist.net, and follow me on Instagram @danrubinstein. And don’t forget to follow The Grand Tourist on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you like to listen, and leave us a rating or comment. Every little bit helps. Til next time!

(END OF TRANSCRIPT)

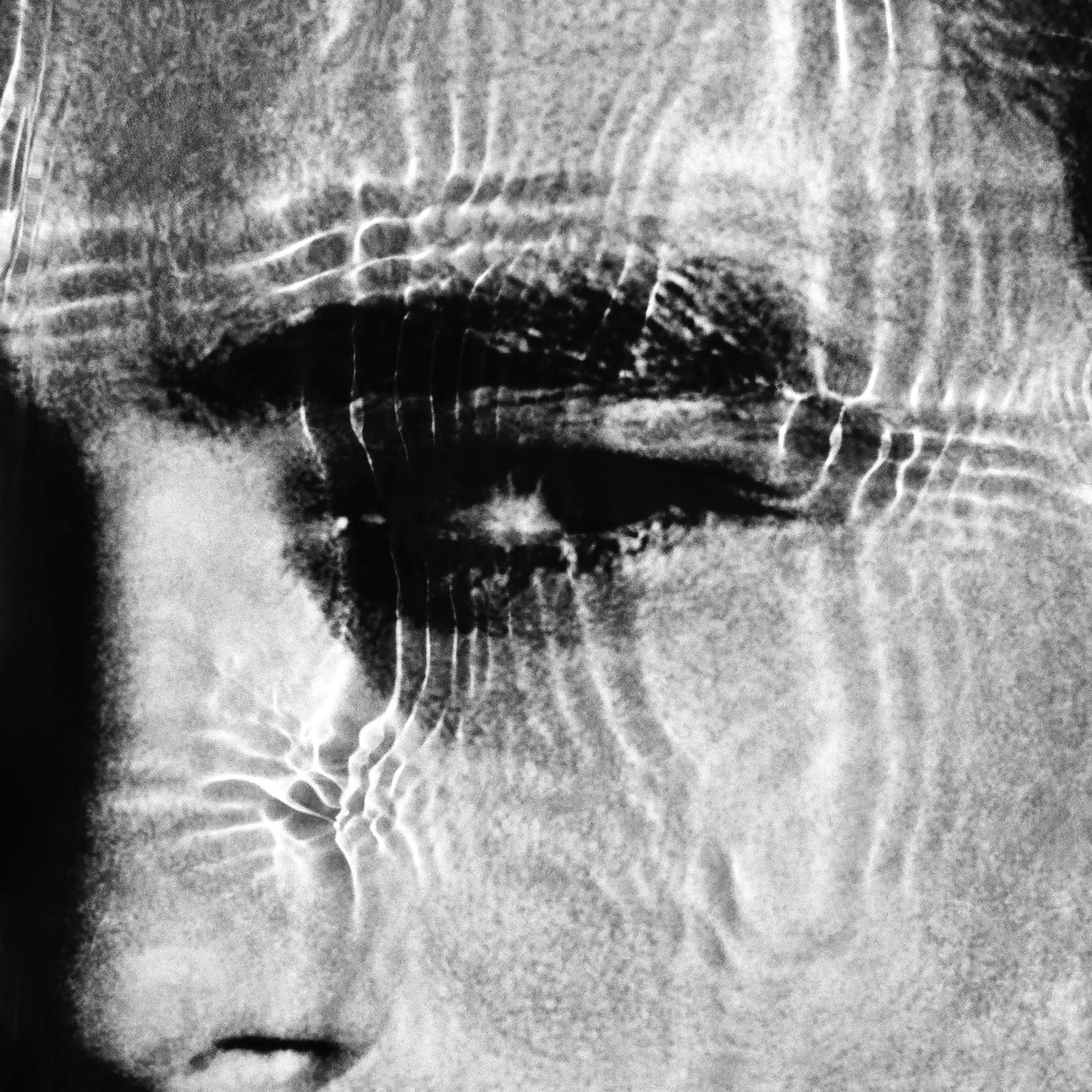

The newest gallery openings this week, including the dark side of the American dream, traditions of Aboriginal Australian painting, a cheeky photographer, and more.

For Italian fashion photographer Alessio Boni, New York was a gateway to his American dream, which altered his life forever. In a series of highly personal works, made with his own unique process, he explores an apocalyptic clash of cultures.

Plus, an exciting young British artist receives a retrospective, Marcel Dzama's whimsical drawings take a political turn in L.A., and more gallery openings.