Annie Leibovitz Shares Her Vision in Monaco

The newest gallery openings this week, including the dark side of the American dream, traditions of Aboriginal Australian painting, a cheeky photographer, and more.

One of the most skilled and thoughtful architects today, David Chipperfield applies his vision to everything from museums and grand public spaces to office towers and luxury retail flagships. On this episode, Dan speaks with the maestro on how he got his start, his famed rebuilding of Berlin’s Neues Museum, his second life in Galicia, Spain, and more.

Sir David Chipperfield: I think in the Anglo-Saxon world, we’ve been taught that happiness comes with wealth and with consumption. From a sustainability perspective, that’s not going to work much longer. And if we’re going to deal with consumption, we have to deal with aspiration, desire, and happiness, and we’ve got to break that circle that you must want things and you must become happy by wanting and confusing need with want.

Dan Rubinstein: Hi, I’m Dan Rubinstein and this is The Grand Tourist. I’ve been a design journalist for nearly 20 years, and this is my personalized guided tour through the worlds of fashion, art, architecture, food, and travel, all the elements of a well-lived life. My guest today is an architect’s architect. To me, he’s the textbook definition of substance over style. That’s not to say his works aren’t alluring, quite the opposite. They have that special quality and design where upon looking at any completed project of his, you can’t imagine it being any different or any better, Sir David Chipperfield. First the basics, for those of you who don’t know him, he was born in England and raised in a farm in Devon, and later studied at London’s Architectural Association in the 1970s. He then cut his teeth working for other greats like Norman Foster and Richard Rogers, and started his own firm in the 1980s.

While he’s renowned for his museums and other grand and important works, he got his big break in retail and stretched his legs in the most unlikely place, Japan. A shop for Issey Miyake in London led to commissions in Tokyo and Kyoto and his career grew from there. The most pivotal page in his portfolio, however, is probably the reconstruction of the Neues Museum in Berlin. The stunning project blended old and new and inspired a generation of architects to think about modernity in a whole new way, more on that later. Today, he has offices all over the world and his reputation seems to be when you have something important and monumental that needs to be done right, you call David Chipperfield. His latest masterwork is, forgive my Italian, the Procuratie Vecchie on Venice’s Piazza San Marco originally built in the late 16th and early 17th centuries.

The historic structure sits along the entire north side of the public square, and his interiors definitely weave old and new together in the most sensitive and responsible ways. I caught up with David from his home in London to talk about his first residential project he did for a photographer Nick Knight, the legacy of his museum in Berlin, his goals for being named design advocate for London, and his family’s second life of sorts in Galicia, where he has a home, restaurant and nonprofit, looking to bring good design to a neglected corner of Spain.

So, I read something about your early life that you worked on your father’s farm in Devon as a young man before going to boarding school, and I’m wondering if you could share a couple of your memories of that time. What was the farm like?

It was quite small. My father was an evacuee during the war. I mean, he grew up in London and they took all the kids out of London for a few years and he spent time in the countryside and I think that sort of impressed him and he carried that image with him for a long time. And then he was an upholsterer. He was quite a success when he run his little company and did quite well. And then, when he was in his late twenties, he decided he wanted to be a farmer. So we moved, lock, stock and barrel to Devon and he bought a fairly hopeless farm, rather prettily located. And we had a bit of a Noah’s Ark. We had two of everything nearly. And he learned how to be a farmer. It’s a sort of school of hard knocks and gradually specialized in pigs and different crops.

How did you, as a young man…what about architecture appealed to you?

I was very fortunate. A boarding school is a sort of mini society. You have to, it’s weird, but it’s a mini society without women or girls, which is slightly kinky, I mean it’s not…And not to be…I think now they’re much more modern. I think they’re mixed schools, but in those days it was a bit of a monastery, but you had to be good at something. And I wasn’t academically very good, but I was good at sports and athletics, and I was good in art. And I had the fortune to have a really great art teacher who took me under his wing and encouraged me and pushed me and gave me confidence, which I didn’t have in my other subjects. And he really got me excited about being an architect and encouraged me that way.

And so after graduating, I think you worked for Norman Foster for a few years. Is that true? And what was that experience like? How did you get the job?

I worked for Richard Rogers first, and I got that job ’cause I happened to know Richard, and my first commission for him was to find a studio for him ’cause they had to move offices. And I worked on a lot of competitions. I worked on Lloyd’s competition, then I worked for Norman Foster on a part-time basis, and I worked on the BBC competition, which we won. And because I was of…I was leading the competition team in fact, at that point, Norman kept me on to work for a few years on that project. And as soon as that project looked like it wasn’t going to happen, I decided to leave. But they were good years to learn about professionalism. I mean, both offices of very high professional performance and it was sort of unusual in England in a way, which was much more, the architectural profession was much more shambolic and typically sort of historically a sort of gentleman’s profession and a bit old-fashioned. And so, the Foster and Rogers offices felt very exciting.

And that was…What year was that? That was like early ‘80s?

Yes, exactly that.

Yeah. And I mean, that brings me to my next question is that time in London was so tumultuous is when we think about London at the time. And you mentioned that architecture had that kind of, as you say, shambolic kind of gentlemanly thing. What was on your mind when you were in those offices and working for people like Norman Foster and so on? What were you trying to do with architecture in the world that I think that you think at the time was that you were radical or you were trying to put out into the world?

I’m not sure. I mean, I think the generation before us came out into a slightly different notion of profession and probably a society where the profession was probably held in slightly higher regard. The post-war period in Britain, I think there was…Architects were valuable, they were useful, and there was a great enthusiasm and optimism about planning a new state after the war. And obviously with strong welfare tendencies in terms of building new schools, building new universities, building new housing. So there was in a way a sort of coincidence of international modern movement, ideology and social predicament of building a new society. By the time I came out of architecture school, that vision and that dream and that optimism had slightly tanked. And the general attitude amongst society was not only was the state in a mess, certainly in the UK, I mean we had deep recession.

Margaret Thatcher was reinventing society or stripping society back, questioning sort of conventional public structures. Trying to free the free market, trying to make us, let’s be clear, more American in that sense. At the same time, popular opinion had turned against planners and architects because evidence that they had left on the ground wasn’t giving them the sense that we were building better. We emerged from college in a commercially bad period. And I would say from a professional point of view, sort of spiritually bad period, and one where the profession itself was sort of intellectually trying to rethink its position, both in terms of intellectual direction and also social position.

(SPONSOR BREAK)

And some of your earlier work was in retail. And I’m sort of curious about if you think that that foundation kind of made you a better architect today or perhaps helped you on that kind of trajectory. What do you think about when you think about those early retail projects?

It was survival. I mean, it was a way of being independent. I left Norman Foster’s office and did a shop, which was in one sense a sort of peculiar thing to do because I had the opportunity to work on, to be part of a bigger team on bigger projects. And I think that it’s a question that faces all young, arrogant architects, you know, should I work for somebody else? Should I try to work for myself? There’s no real script to follow about being an architect. It’s not easy to know. And I suppose I just took a gamble in thinking that that’s what I wanted to do. I was never really…I mean, I admired and I enjoyed working in those offices, but I didn’t ever feel it was where I wanted to be, but whereas previous generation may have aspired to doing a university building, we were happy to get a small shop or bathroom extension for someone.

So, it was the way of striking out, I guess. But the difficulty was then how to proceed from there. Michael Graves famously said, I did someone’s kitchen extension ’cause I thought it would lead to doing a house, and I thought the house would lead to doing a museum, but actually it just led to more kitchen extensions. That was a little bit of a problem, but certainly the shop I did, the first shop was for Issey Miyake, and then Issey invited me to Japan. So it gave me… I was going once a month for five years nearly to Japan, and it was during the bubble period. And although the work for Issey was of limited architectural scope, culturally, it was a great experience. And through Issey, I met a lot of people. And then I, in fact, the first three buildings I did were in Japan. So that strangely, that one shop led me to do the type of projects of which I’d never have managed to have got here.

I mean, that bubble period in Japan now is almost like the stuff of legends. And I’m curious, what was it like when you would go to visit Japan for work? I mean, had you visited previously as just as a tourist or was your first time there kind of working there?

No, my first time with there was working there on a two-day notice. I got a call from Issey saying, “Could I be there before Christmas?” ‘Cause Japan, they don’t…Well certainly those days they didn’t celebrate Christmas. They do a bit now from a commercial point of view, but they celebrate the end of the year and the beginning of a new year and business has to be finished. So, invariably there’s a lot of deadlines and things have to be done before. So I always found myself there at the end of the year to finishing…Anyway, the first time I went was on short notice to go there. And it was a total shock, but a wonderful shock. And yeah, it was great experience.

And I’m also curious about another sort of a slightly earlier project, which was the home for photographer Nick Knight, which you kind of expanded on later on, and it was an incredible house in a very suburban neighborhood, from what I can tell. What was that like in that brief and how many homes had you done up until that point? I’m just curious where that falls in your timeline.

No, that was the first house. I think it was the first free stand…

Well, it wasn’t really a freestanding building. We were converting the house that Nick’s father had built and extending it into a new house. And yes, I think that was the first piece of architecture. And of course working with Nick was wonderful. It was great fun.

And what was a photographer like that as a client? I would assume that, you know, I think when people think about fashion photographers and people like that, that they have really expressive views and I don’t know…But the home itself is of course looks very serene and peaceful. And I’m kind of curious what that conversation with him was like. What did he ask for for a home from you, especially if it was your first ever?

No, Nick was the easiest person to work with. I mean, he’s totally respectful. He’s a professional, he has utmost respect. I mean maybe too much respect for other professionals. So, there was no issue about that whatsoever. And we have very similar tastes and he was similarly enamored of things Japanese at the time. I think we all were at that time. There was a lot of influence. He was doing all the work for Yohji Yamamoto at the time with Peter Saville. So there was a sense of commonality in terms of a belief in modern things, a belief in…A sort of excitement about what was happening in Japan. Yeah. So it was a great modest size project retrospectively, but of course at the time it was a great opportunity for a young architect to start starting off.

Is there anything in that project that you think is unmistakably yours in a sense that if someone would put this in a monograph of yours, far in the future, what do you think they’re going to say about that particular home that maybe says, “Obviously this is David Chipperfield’s project because of X.” Do you think that there’s something there that you could think that is close to you as who you are as an architect?

I don’t think so, and probably less and less because at the time we’re talking about early ‘80S or mid-‘80S, there wasn’t much. Modernism was in a sort of strange place. And so typically, especially in England, the prevailing taste was quite conservative. In fact, we had real problems with that project with neighbors who were very objecting to our proposals. But I think it was in those days doing something which was sort of strict and to some degree minimal, if we can use that word. And yeah, modern…It sort of stood out, whereas however many years later, nearly 30 years later, I guess it would probably look pretty normal by now.

(SPONSOR BREAK)

Built in the mid-19th century. The Neoclassical Neues Museum sits on the famed museum island in the heart of Berlin. It originally housed Egyptian artifacts and other antiquities as it does today, and closed during World War II, allied bombing heavily damaged the building where it laid, dormant and decaying until David Chipperfield came along. Instead of simply restoring it to its original condition, like a reproduction, he leaned into it inserting stark modern elements and embracing the surrounding rustic original stone and brick walls. It was controversial, especially for a state-owned institution, but David’s ideas and approach won out and it made him a champion for grand progressive ideals and architecture and propelled his career forward, not just as a designer, but as a thought leader.

I wanted to ask the architect about this pivotal undertaking to try to figure out what makes him tick and discover the roots of his process.

And jumping ahead a little bit, I mean, one of the major projects in your career, of course is the Neues in Berlin, which was I think a 10-year project to say the least. What do you think that project says about your particular approach to architecture today if you’re speaking to someone who doesn’t know you or your portfolio at all?

Well, the Neues Museum was a sort of unique opportunity, a unique commission in a way. In some ways, a bit ambiguous At the beginning, it was a ruined building that it’s stayed ruined for more than 50 years since the Second World War. It found itself as it were, on the wrong side of the war during the GDR period. The complexity of the damage that the building had suffered and the complexity of the original building and the ground conditions had somehow stopped it being repaired. Although during the GDR period, they’d started to replan finally a restoration. So rather strangely, when the wall came down, it was standing there as a war room stabilized a bit, but on the other hand, being progressively ruined by 50 years of Berlin winters. So we were dealing with a very complex piece of history and something which clearly had deep resonance in Germany and especially in Berlin of course, because it was a sort of time warp, forced one to confront the reasons that it was damaged, the reasons that it hadn’t been fixed and et cetera, et cetera.

So, the approach to how one dealt with this was not just an architectural one, it was a philosophical one, but how you deal with such issues in painting and archeology, it’s fairly straightforward. You repair and protect and stabilize the damage, but you wouldn’t necessarily imitate the missing bits of a sculpture or missing parts of a painting, but you would certainly try to harmonize it. But with architecture, which is what we wanted to do, it’s not so easy to do it, and although intellectually it’s the correct way, technically it’s difficult. And emotionally for people of Berlin, it was quite difficult because to some degree they wanted to see the building repaired and restored and back to how it was, we resisted that and saying, “This building needs to be working again, but the restoration of it should include its history. We shouldn’t lose the qualities that physically evolved through its ruination or the memories that it carries through that ruination.”

It wasn’t meant to be a war memorial, not at all. And I think it’s regarded as a sort of positive dealing with history, which is what we intended it to be. But it was extremely complicated project and it forced us to develop a very participatory design process, which has very much formed my way of thinking and my way of working. And I think that the work of the office is very much shaped by that profound experience.

Now with hindsight, because the museum was controversial or at least had people that, as you say, wanted it just to be the way it was or almost restored something that is almost completely was destroyed. When you think back about that debate and think about how those debates are going on in architecture, what would you like to let people to know as a record of how these conversations happen in architecture? With hindsight, do you kind of wish that you just did it the same way as you had? ‘Cause you mentioned that it changed your practice also and probably for the better. And so I’m thinking, is there an issue with the discourse of architecture occurs in places like London or Berlin or New York or any kind of major western city that you kind of wish you could make a change in how we approach this conversation for major projects like this because you have this experience?

Well, I think the problem is that the discourse hardly exists. And the good thing about Germany, and especially Berlin at that point, which was as it were trying to find its feet again because the reunification, the taking down to the wall meant that Berlin had to once again reinvent itself. It meant that there was a high level of discussion about how that should happen. And discussion in Germany is always fairly rigorous and robust and reflective. And I would say to a degree, which doesn’t exist in London and doesn’t exist where investor momentum dominates all other considerations. And I think that’s a big problem. I was a big…I mean even though the discourse was to some degree painful and laborious and procedural, and a lot of my German colleagues kept apologizing for what we had to go through in terms of even demonstrations outside the building and et cetera, et cetera, I was always a big fan of it, and I always was very encouraging to say that I think discourse is good, and if we want people to feel strongly about architecture, then we’ve got to let them say things.

I mean, whereas I would say in the Anglo-Saxon culture, we’ve become too convenient to the idea that the city is at the behest of investors, and we haven’t found a way of convincingly including any other level of dialogue or participation. As we go forward and as we find ourselves in existential crisis of global warming and sustainability, we are going to have to change our ways of thinking and we’re going to have to include points of view, which are not only to do with expediency and financial return. On the contrary, we’re going to have to put those things in their right place. In order to do that, we’re going to have to rethink the whole way of controlling planning and the way that we…Where we build what we build, how we build. It’s not just going to come from insulating our roofs or using better window frames.

So, we have to tackle that seriously. And if the global warming crisis wasn’t enough, we also have, I think, probably something just as worrying, which is social inequality. And social inequality is also the consequence of bad planning or inconsiderate planning or leaving people behind. Where we live, how we live, what our schools are, what the streets our kids play in. All of those things profoundly affect potentially in a positive way, the quality of life and in a way, our way of sharing our wealth. I don’t believe that everything is done through philanthropy and good deed. I think we actually have to engage this. And so I think we’re going to be forced into a more participatory process that planning is going to become important again. We’ve tended to soften it. We’ve softened it because a soft planning environment is very encouraging of investment, a hard planning environment is discouraging of investment.

So, I think cities have been nervous about imposing restrictions and demands because they’re worried that that puts off investors. But I think now we’ve realized that our challenges are quite significant now and planning is if we’re going to have any idea of a circular economy or any things which are integrated in terms of challenging or standing up to these challenges, we need planning. You can’t do it without whatever type of planning one means, but in terms of governance and procurement, this is going to be important. And I think architecture is going to have to tuck in there somewhere. Architects, the architectural profession is going to have to tuck in there somewhere. And I think the days of doing signature amazing museums that are put on color supplement covers are probably over. And I think the profession has to think about being slightly more purposeful. That’s not to say that architecture isn’t important. It’s not to say that design’s not important. It’s fundamentally important. I think we have to find ways of sharing it out a bit better. We have to think about ways of improving our general physical environment, not just special moments.

And when it comes to…It brings up an excellent topic, which was my next question, which is that you were named a design advocate for London recently by the mayor. And I’m curious from…What does that mean in a ground floor way? And London of course is…London and all of the UK, but London specifically is at a unique crossroads in that it has its own issues, but then it’s also of course in the center of a swirl of lots of different issues going on for the UK. And I’m curious, what are your goals for this? What have you done? And if you had a magic wand, what changes would you make or what would you want to advocate for in terms of how London will move into the future?

Good question. I’m not sure. I’ve only just gone on board with this particular bus, and I’m not sure I’m going to be doing much more than the sitting in a backseat somewhere, shouting a bit, maybe shouting at the driver occasionally. But if you ask me what I’d advocate for, I would advocate that we have to build more social housing. We have to find ways of limiting the increase of land value. Because if we just carry on with the notion of keep escalating the value of land, then we find ourself and the next generation finds itself without being able to afford housing. And we also empty out our cities because our cities are no longer places where people live. They’re just places where people invest and become sort of shopping centers and tourist centers. So, I think we have to start looking through the telescope the other way around.

We’ve got to think about what creates a better city for citizens and stop looking at how to bring tourists and how to bring investments. I’m not saying we don’t need investment. I’m not saying we don’t need tourists, but I think they have to be part of the tools, not the aim itself. It’s difficult to know to what degree one can have much influence, but I think general societal shift, which means that mayors are much more interested in issues that they might not have been interested 10 years ago. Controlling traffic, reducing dominance of traffic in city centers is clearly now a shared issue. Trying to improve the quality of public space and social infrastructure is I would say a shared issue. To what degree politicians and local politicians are successful on this, we’re not sure. But the first issue is to at least admit that these are priorities…Being optimistic, I get a sense there’s a shift in that.

And you recently completed your project in Venice, and I was wondering if you could tell me how that came about and wondering if you could describe it for our listeners.

It’s a project not so unfamiliar to us. I mean, since Neues Museum and even before, we have been engaged in restoration projects or projects where there is a heavy component of history and existing buildings and often existing buildings which are badly treated or have suffered through bad modifications. And so we’ve worked on a lot of buildings like that, especially in Germany, but also some in Italy. And of course, being on St. Mark Square, this particular project has great importance. It’s the north side of the square buildings owned by a Generali insurance company. And in fact, where they began their life many years ago, they’re now, as it were, taking back their seat in the city and have demonstrated, I think, admirable responsibility by investing in the building and renovating it and following our direction to try and respect the history of the building and the qualities of the building which are still intact.

And to elevate the, or at least to integrate the good bits with slightly better interstitial spaces, which had been treated badly or to take away staircases, which have been badly put in, or all of those things that buildings suffer over a long period of time in a sort of expedient way. So we’ve brought some integrity back to the building. And while that’s not so difficult, let’s say, and for a museum like Neues Museum or something like that, it’s much more difficult to do it in a commercial climate with a private client. You’ve got to persuade them that doing things slightly better than they might need to reflects on them well, and that you’ve got to convey to them that doing this option instead of that one may penalize you financially, but will pay off in the long term. And also things which you can’t tell that well before you do it, but luckily they are delighted with the results and they’ve been very supportive through the process.

And I’m curious, anyone who…I think anyone who knows a little bit about architecture and design and visits Venice, they kind of realize it’s still stunning that this place still exists and is still standing and the way in which it’s built and the way that which it’s been sort of love lovingly kind of kept up all this time. Is there anything that you learned, obviously from a project of this scale and complexity in Venice that you learned about Venice itself and the architecture or maybe the design culture of Venice that maybe if you wanted to pass on a hint or a tip to anybody doing a project in Venice, what would you say?

Oh, well be prepared for time. Planning in Italy is always complicated, and Venice is particularly complicated to some degree, correctly because it needs to be done carefully. I would say that the thing that I always take away from Italy, because we work quite a lot in Italy, we have an office in Italy. While there are distinct characteristics, let’s say that with the Italian situation, the one thing that is always so enjoyable and reassuring is the quality of craftsmanship. That the skills are still there, the sort of common understanding of quality is there. So if you’re on a construction site and you’re reviewing how something has been done, it’s an intelligent and open-minded discussion as opposed to a highly contractual one that you might have in London where the contractor is only interested in defending his position.

It’s a delight to work with skilled Italian craftsmen, whether that’s repairing brickwork or stitching leather. There is a culture of making, which we all have somewhere. I mean, every culture still has it in bits, but Northern Italy, through the whole design culture, the furniture industry, the fashion industry has more than its fair share. And that culture needs to be protected somehow because there’s skills which are getting lost.

And I’d love to ask you before we run out of time about this, the town of Corrubedo in Spain. It’s become a big part of your life and you have a foundation there. And I’m curious what about that part of Spain sort of captured your heart?

We started going there 30 years ago. I was traveling a lot through the whole year. And so the deal I had with my family was that I would spend at least four weeks with them every summer, which grew until it became six weeks every summer. And I tried to stay there through the summer and we sort of grew up there, blissful summer holidays in a very untouristic region, a very natural area and in some ways tough area, but it was great for the kids, I think, to be in such a…Not really the right word to say, real. You know, a real place, I mean authentic is an overused, but I think you know what I mean, it hasn’t been spoiled. And I think we have all loved the directness of Galicia as being rather an antidote to what we experience in London, where London, everything is overinflated and overdone and over-opportunized.

It’s very nice to be in a community which is much flatter, socially and economically. Divergence between rich and poor is much more extremely flat. A place where the landscape and nature is so powerful. And so it’s been very much part of our lives. And in the last five or six years, I set up a foundation. The president innocently asked me six years ago, couldn’t we advise them? And I advise the government a bit on the planning because as beautiful as the nature is, the towns and the villages are extremely ugly. They’ve really messed them up with bad planning, bad traffic plans, bad architecture. And so for these last six years, we’ve developed this program. I have a team of people there now. We have a building in Santiago.

In fact, now we have a foundation and next year we will open our headquarters there, which will have an exhibition space, we’ll have a conference space, we will have a public program, we’ll have residential courses, which will play out with other institutions doing research on protection development for built natural environment. And we are working with the regional government on sustainability policies and trying to, as it were, go higher up in the decision-making process to see whether we can influence planning policy, which seriously addresses the way we protect our environment.

What is the perfect weekend, just there, just spending time there to get out of London, let’s say. What is the perfect weekend in Corrubedo, like for you?

Well, a little bit of time on the water at some point. Sailing.

Do you own a boat?

Yeah, we have a sailing boat. Just a very nice day boat. And we run a bar. So I guess somewhere in the weekend would be spending time in our bar. And swimming, yeah. And going for a walk. I mean, there’s always a lot to do there.

Tell me about the bar. Does it serve food or is it just drinks?

It serves excellent food? No, ’cause over the 30 years we’ve ended up always bringing a lot of people there. Our summers, pre-COVID, were normally 20 or 30 people at any one time. I would cook every night, and at some point someone said, “You should run a bar. You’re running a bar already. You’re running a restaurant already. Why don’t you…” So stupidly, we decided during COVID that that’s what we would do. The reason I enjoy cooking there is ’cause the materials are fantastic. I mean, everything is local. Everything is straight out of the sea.

What should I order? I’m curious, what should I order at the bar?

All of the shells, clams, mussels, all of those things, all of the crabs and lobsters and those things. Very good fish, especially sardines, basic things. But everything is totally fresh. Everything is a local cook. It still has to use again this horrible word, certain authenticity about it. And it’s part of the thing that we are interested in celebrating, I guess, there trying to remind the local community that sometimes overlooks in the desire to think that things might be more exciting in London or other places, especially the young generation that wants to leave. I think one of the things we’re trying to do with the foundation, but also even with the bars, to bring attention to what’s there and to remind people that might take it for granted. And I think for me it’s a fascination because it has not high economy. I mean the GDP per capita I think is something like $23,000 a year.

So, it’s a very modest economy. But I would say the quality of life is very high. They just did a census and one of the statistics was a happiness index, and this year the happiness index fell by 2% from 86% happiness to 84% happiness. That’s a pretty impressive statistic in any community. And I would say that it’s anecdotally, probably correct, and I think it’s a lesson, and that’s why we’re interested in this in the foundation, that one of the things we want to in a way bring attention to is this particular community region of two and a half million people. This is a very romantic outsider’s perspective, but that there is some message in there.

I believe that if we’re really going to deal with sustainability, we also have to deal with consumption. And if we’re going to deal with consumption, we have to deal with aspiration and desire and happiness, and we’ve got to break that circle that is now so embedded in our culture that you must want things and you must become happy by wanting and confusing need with want. And we need to break that circle somehow in any way. So for us, Galicia is very much part of that debate.

And I guess as my last question, a few years ago you were a guest editor at the legendary Italian design magazine, Domus, where you wrote a cover story called “What is our role?” So I’m curious if you could summarize that for the listener. If I asked you, what is your role in the world, Mr. Chipperfield?

Well, what I wanted to do during Domus and what I had started when I was director of Venice Biennale, where I similarly invited my colleagues to the title of my exhibition, my Biennale was common ground. I was interested for the people I invited to not discuss how clever they were individually and how better they were within their colleagues, but in a way, what we shared together and what we offered as a profession. What we shared not only amongst ourselves, but as it were with society. And that was a theme that I took up in Domus, which was to say, what is the role of the architect now? And especially given existential issues that we now have to confront. And so I took it as an opportunity to do what you just did to me. Ask architects to say, “Well, has the current situation and the changing environment, has it had influence on the way they practice? Should it have influence on the way we practice and what way might that be?”

I think our answers are similarly vague and imprecise, and they’re not much different to the rest of all of us. We all know that we need to refocus ourselves and think about how we change habits and considering… And we all think about what contribution we might make personally. We all have a sort of feeling that, does it make much difference what I do? We all know that if we all say that, then we’re not going to get anywhere. So we oscillate between optimism, thinking that we can modify the way we live and pessimistically thinking that we’re not going to. Clearly COVID gave us an opportunity to think that it’s possible for us to live differently as directed directly to me wearing my professional hat. I think all our offices are really trying to address this issue as much as we can within the constraints of commercial practice.

And obviously commercial practice has limits because if we scrutinized everything we did, we’d probably close the door and no one would get in. So, we are trying to shift direction. We’re trying to think deeply about how we build. We’re trying to think about who we build for, and we’re trying to influence the habits of our clients. We are certainly taking a strong stand on trying to persuade clients, knock buildings down in redevelopment projects. We’ve just won a competition with London School of Economics by insisting that the competition rules should be rethought, and we insisted that the building should be renovated and not rebuilt, and we’re getting traction on those things. And finally, I would say yes as another contribution, the work we’re doing in the foundation is clearly taking up now a lot of my time. It’s becoming part of the group that is, in a way, acting in a non-commercial manner.

So therefore, we’re operating more freely, although under other sorts of stresses. But in a way, we are becoming, we’re trying to invent a practice that instigates its own projects. So we create the projects ourselves, we provoke the project, and we’re getting a lot of support from government on this who are, I would say, being very open-minded about this provocation. But it’s taken us six years of real frontline hard work, really on the frontline with communities participating, doing field research, doing studies, doing tiny little things. And I’ve had to persuade architects in my team to give up building. And we are, instead of doing competitions, we’re advising institutions about how to do a competition properly. And we’re doing very modest interventions, but essentially, we’re trying to shift our role substantially.

A special thanks to David Chipperfield and Alessandra Coral for making this episode happen. The editor of The Grand Tourist is Stan Hall. To keep this going, please follow me on Instagram @danrubinstein to learn more and sign up with your email for updates at thegrandtourist.net. And don’t forget to follow The Grand Tourist on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you like to listen, and leave us a rating or comment. Every little bit helps. Til next time.

The newest gallery openings this week, including the dark side of the American dream, traditions of Aboriginal Australian painting, a cheeky photographer, and more.

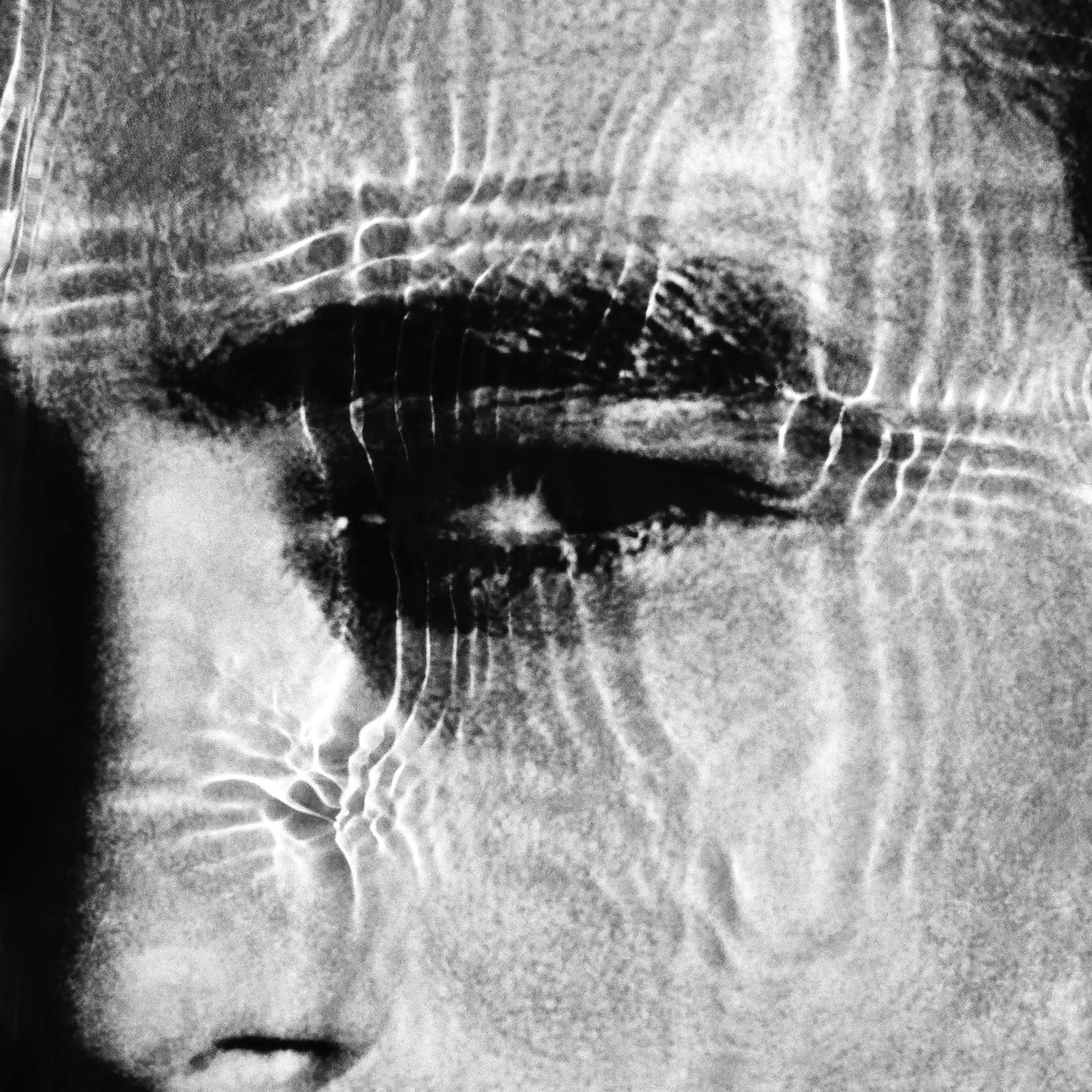

For Italian fashion photographer Alessio Boni, New York was a gateway to his American dream, which altered his life forever. In a series of highly personal works, made with his own unique process, he explores an apocalyptic clash of cultures.

Plus, an exciting young British artist receives a retrospective, Marcel Dzama's whimsical drawings take a political turn in L.A., and more gallery openings.