Annie Leibovitz Shares Her Vision in Monaco

The newest gallery openings this week, including the dark side of the American dream, traditions of Aboriginal Australian painting, a cheeky photographer, and more.

As the genius chef behind New York’s Eleven Madison Park, Daniel Humm is at the forefront of fine dining culture. And in 2021, he shocked the food world when he turned the Michelin three-starred restaurant completely plant-based. On this episode, Dan and Daniel chat about his new book, “Eat More Plants: A Chef’s Journal,” how he started his career in cooking at the tender age of 14, what it was like emigrating to the United States, how he handled the criticism he faced when he put his beloved restaurant’s reputation on the line, and his thoughts on french fries.

TRANSCRIPT

Daniel Humm: Because it is so set in stone what a meal in a fine dining restaurant is. It’s always the same kind of proteins. In a way we were just cooking seasonal condiments, one day the lobster was with lemon, then it was with rhubarb, then it was with onion, but the lobster remained. Today I feel like we’re cooking really fully entire meals, where every ingredient on the place is of this season is of a farm and you can taste the weather and the farm and the terroir and all this, and it’s really quite poetic.

Dan Rubinstein: Hi, I’m Dan Rubinstein and this is The Grand Tourist. I’ve been a design journalist for nearly 20 years and this is my personalized guided tour through the worlds of fashion, art, architecture, food, and travel. All the elements of a well-lived life. And welcome to the last episode of season eight. This has been our biggest season ever with the most episodes, the most sponsors and events, a brand-new website and a new newsletter called The Grand Tourist Curator. So I just want to take this moment to thank everyone who made the Grand Tourist possible this year. We’ll be back with new episodes on February 7th. So in the meantime, make sure you sign up for The Curator at our website thegrandtourist.net and follow me on Instagram @danrubinstein. We’ll be sharing news and original features outside of audio, so I hope you’ll join us.

My guest today is arguably one of the most successful chefs in America, if not the world. And also perhaps the most daring. As the chef and owner behind the New York landmark restaurant Eleven Madison Park, he’s helped to redefine fine dining and raise expectations across the board. And like our other guests this season, Yves Behar, he’s a Swiss transplant who became creatively invigorated by his adopted American home. Daniel Humm. Humm first moved to San Francisco and then to New York to become the executive chef at Eleven Madison Park in 2006, recruited by the famed restaurateur Danny Meyer. He purchased the restaurant from Meyer in 2011, today his company called Make It Nice, runs Eleven Madison Park, as well as its sister lifestyle brand Eleven Madison Home. Humm earned his first Michelin star at 24 in Switzerland. Since then, he’s put Eleven Madison Park not just on the map, but made it a seemingly godlike institution in the pantheon of the great restaurants of the world, famed for their extensive tasting menus that changed seasonally.

When the restaurant was ranked number one in the world and had three Michelin stars, the pandemic hit Eleven Madison Park and indeed the entire dining world hard. And when it reopened in 2021, Humm shocked the food world by announcing that his beloved restaurant was going 100% plant-based. At first the reviews were not kind.

Pete Wells in The New York Times wrote quote, “At Noma, these sauces are administered so subtly that you don’t notice anything weird going on. You just think you’ve never tasted anything so extraordinary in your life. At Eleven Madison Park, certain dishes are as subtle as a dirty martini,” End quote.

Ouch.

But I’m sure you know where this is going. The following year, it became the first and only plant-based restaurant in the world to receive the coveted three Michelin stars. Humm is also an accomplished author, speaker and turned Eleven Madison Park during the pandemic into something of a soup kitchen. More on that later. His latest book from art publisher Steidl called Eat More Plants. A Chef’s Journal, is filled with his own sketches and notes on plant-based cuisine and is available for preorder now online.

I caught up with Daniel from, where else? Eleven Madison Park to discuss growing up in a hippie household with an architect for a father, how the tradition of Eleven Madison Park’s famed granola got started, how and why he made the big leap to a plant-based menu and what he really thinks about french fries. I caught up with Daniel from, where else? Eleven Madison Park to discuss growing up in a hippie household with an architect for a father, how the tradition of Eleven Madison Park’s famed granola got started, how and why he made the big leap to a plant-based menu and what he really thinks about french fries.

(MUSICAL BREAK)

Well, I guess I wanted to start at the beginning. You were raised and your career began in Switzerland before moving to the States. And I read that your father was an architect and as a design journalist that got me excited. What was home life like for you as a kid?

I was growing up in Zurich and my parents had me very young when they were 17 years old. So my dad was, they were in school and then eventually architect school. And so I saw my dad growing into his career, which was pretty amazing because usually when someone has kids at a much older age, then you just see the final version of your parents. But I really got to see how they both grew and grew up, which of course at times is good and bad because maybe certain things are less stable as we’ve moved around a lot. And I also had a challenging relationship with my dad, but otherwise it was super helpful to see just how through hard work you can bring it quite far and you can make a difference and create beautiful things.

And I read that your mother raised you to revere ingredients and passed on a love of cooking in that way. Is that correct? What are your earliest memories of food?

My parents were just hippies. And we were eating mostly plant-based. We ate meat very seldom. And then all the ingredients came from a farm and were organic. And at that time I always thought the way we were living was weird. When I was with my friends, I was almost embarrassed the way we were doing things. Not realizing at that time how privileged I was really, because everything was from the farm. I remember this one moment, I was in the kitchen and we had this mache salad that my mom just brought home and it was raining outside and the salad was just covered with dirt and we had to wash it and wash it and wash it like five times.

And I was just standing in the kitchen there and wondering why does it need to be this complicated? And then there was this moment where my mom, I guess could see me wondering and she would pick out this lettuce out of the cold water and she would say, just taste this lettuce and see how sweet it is and the texture. And I remember this moment to this day, and it was actually a pivotal moment. I started to understand the reasons to go through great lengths to achieve very special tastes, as well as that amazing taste can come from the most humble things.

And how you started working at a restaurant when you were 14. So I’m wondering how did that happen so young and what was your parents’ mindset? How’d you wind up taking that path?

Yeah, the story really is that I left school when I was 14 years old and I was pursuing a career as a professional cyclist. And my parents were not excited about this idea and my dad was saying, “Look, if you make this decision, you’re on your own financially.” And so I was quite rebellious at that time, so I was like, “Okay, fine. I got this.” And the only job I could find as a 14-year-old was in a kitchen. And then I continued to ride my bike and race my bike and I continued to work in kitchens and I was lucky that I found a mentor who was actually giving me much more than a job, but also an education a little bit in the kitchen.

And when I was 22, I had an accident riding my bike and I was in the hospital for a while. And at that time I was laying there and I was like, “Wow, what is my future? And maybe my future is in the kitchen and not on the bike.” I was a good cyclist, but I wasn’t the best and it was a very competitive environment and it’s dangerous. And so I took the athlete’s mentality towards the profession of cooking. I wanted to work for the best, I wanted to be the best. I wanted to win awards and rankings and so forth. So at that moment I decided that I would climb this culinary mountain of chasing Michelin stars and Zagat ratings and number one spot in the world eventually. But I’m very much from an athlete’s, winning was important.

Was there ever a period in your career where you thought maybe cycling would’ve been easier?

The truth is that, in a way, cooking often felt like an endurance sport as well. And I think being an athlete for all these years, I was running cross country when I was 10 years old and then was cycling. So many, many years of being an athlete, I think has really conditioned me to be strong on this path. And of course you got to be mentally strong, but also kitchen cooking is quite physical too, so it doesn’t hurt to be also in good physical health as you’re doing these long days in the kitchen.

And tell me about that first boss you had in the kitchen and what that restaurant was like and what you learned there.

It was a traditional hotel kitchen, like a grand hotel in Switzerland with a lot of chefs and quite traditional cuisine. I just learned the most simple task, like how to make a consommé. I thought it was such a magical thing, how to make a consommé. First, how to make a stock and then to clarify that stock and it becomes this essence of… It felt like liquid gold at that time. It just felt magical. Or how to peel an artichoke or how to tourné a carrot or even how to butcher a chicken and all these things felt quite magical. Eggs, learning about eggs and everything you can do with an egg. Making a souffle, how magical, that souffle arises up and it’s just magical. And I’m very grateful that I was in this very classic restaurant because I think that really gave me a good sense of what the foundation is.

(SPONSOR BREAK)

And from there, was that when you went to San Francisco?

I received a phone call from a Swiss hotelier who was running a hotel in San Francisco out of the blue. And he said he was a friend of one of our regular guests at the restaurant that I was working at. And he said, “I’m looking for a chef.” And he heard great things about me and he would love to invite me to San Francisco to come and look at the opportunity. And I was in shock because I never been to America at that point and I never really thought of America as this culinary destination, so it wasn’t on my radar at all. But that being said, I was so young and I was in the middle of nowhere in Switzerland. I knew I didn’t want to be there for the rest of my life. So I took him up on this opportunity. And when I arrived in San Francisco, he personally picked me up from the airport and I remember everything looked different, everything smelled different, but also the sky looked different and even the sky looked like it was much more open and wider and full of opportunities.

And then the next day we went to the Ferry building and we went to the farmer’s market and I saw these artisans and cheese makers and farmers and the bounty of the ingredients. And then the following day we went to Napa Valley and on the way there we ate a Japanese and then that evening we ate at the French Laundry and we were in the wine country and my mind was just completely blown and I felt like there was this energy around food and around fine dining in a way that felt fresh and different than what I felt in Europe. And within the first three days I knew that I wanted to take on this opportunity and a few months later I quit my job and I packed up my things, which wasn’t very much. It was really two suitcases and I came to San Francisco on a student visa.

So definitely in a way, people talk about the American dream. I mean, I feel like that was my American dream coming with two suitcases, a skill, but not even speaking the language. And I didn’t know where this would lead and how long I could stay, but I’m actually now, this year in May, I hit the 20-year mark of being in this country. And yeah, it’s just been an incredible journey and when you pack up your things and you have two suitcases and that’s all you have, there is something very powerful about that, something very freeing. It’s so beautiful when you’re young and you can do that. And yeah, I treasure that moment and I’m glad I took that leap of faith into this new place.

And it was a Campton place was where you worked in San Francisco.

Exactly.

Can you explain to the listener what that place was and what the food was like?

Campton Place is a hotel, it was a family owned hotel right off Union Square in San Francisco downtown. And it was like a boutique hotel. It was run by Swiss general manager. The chef there before was a French chef. It had a pretty intimate dining room and I didn’t know all this, but it had a history of American chefs coming through the doors there over the years. So in a way, the moment I stepped foot in that kitchen and I started cooking, people started paying attention. The critics started paying attention, the foodies started paying attention and everything again, happened so quickly. I remember I’m nominated for Rising Star Chef by the James Beard Foundation. I was only three months in the country and I was like, “Oh, what is this? The James Beard Foundation?” And then people said like, “Oh no, no, that’s a good thing. You should probably go.”

And at that point I’ve never been to New York. And then I was invited to go to the awards in New York and that was the first time I was in New York. And I mean for me it was clear the moment I arrived in New York, the energy and the diversity and this city. I knew eventually I had to find my way here. I ended up being in San Francisco for two and a half years. We had great success. We ended up having four stars by the San Francisco Chronicle, which was the highest accolade at that time you could have there. And from then on Danny Meyer who owns the Union Square Hospitality group and is a great restaurateur, one of the great restaurateurs. He recruited me to become the chef of Eleven Madison Park that at that point was a brasserie serving steak frites and seafood towers. But he had this vision of together we could make this into one of the great dining rooms in the world.

What was that conversation like with him? I mean, what was that first sit down? How does one do that?

Well, at first Danny called me and he said, well, he just had dinner at Campton Place and I have a restaurant in New York City called Eleven Madison Park, and I’m looking for a chef and I think you are the chef I want for this project, I should come visit.

And did you have something in your mind that you were a fantasy of how you were going to pull that off?

I was so scared. Again, I’m still in the country quite new, and I didn’t know who all the players were. I actually didn’t know who Danny Meyer was, and I started asking around and everyone obviously sang his praises. So then, yeah, I came to visit New York and I was so scared because at that point it was a brasserie and it did like 400 covers a night and I’m coming from a three Michelin star fine lining background. I’ve never seen a restaurant that does 400 covers a night. So it was so overwhelming. Obviously it’s not why I was being recruited, obviously the idea was to change that, but still seeing that was so scary. And then of course, I also thought about other chefs who have come to New York. I was a noble name chef at that point, but I was aware of Alain Ducasse coming to New York and not having the best experience and then also being like… The New Yorkers can be tough.

I think I was aware of that, when you come to New York, you got to really make sure you have the best foundation and team and platform so you can really be successful because when you’re not, you rarely get a second chance in New York City. And for me, it was so important to end up in New York that I really wanted to make sure that my first step into the city was in the most perfect situation. And I interviewed with Danny for over 10 months and we met many, many times and eventually I believed in the opportunity. But what really got me here is that I felt like I could trust this man, that everything he’s saying comes from a place of knowing and knowing what it will take because it took a lot to eventually where we arrived. And I have to say that I could have not asked for a better mentor, partner, supporter because he was definitely very, very supportive.

And in 2010, Eleven Madison Park got one Michelin star, but one year later it got three, which is the highest possible. So I’m curious, did you have some sort of plan of action after that first year where you went from, how does one go from one to three? What was that year like?

Yeah, I actually think this may be the only time in the Michelin history that a restaurant went from one to three. It came as a total shock. Honestly, I didn’t even know something like that existed. Well, clearly it didn’t. As I said earlier, the awards were important to me. I had my eyes on those awards and on all of them, even the small ones, I felt like I wanted to win them all. And I thought it was very helpful to be motivated by and to motivate the team too. And it’s measurable, so it actually really, really works even though intellectually I understood that all of these awards, it’s all kind of silly.

It’s all this silly race and it’s controversial and who is really the best or who gets to really say, “Oh, this is the three star and this is the two star.” But I always looked at them as these little carrots in front of me. It gave direction and we were really going after them. So when we got from one to three-star, I mean that was an incredible moment. I mean it’s definitely every European chef’s dream, it’s a dream so big you’re scared to think about, but to reach three stars, it’s the pinnacle of fine dining.

But in that year you didn’t make any changes, it just happened. You didn’t say, “Okay, we got one and I have a checklist of things I’d like to improve in the kitchen or I have new ideas I want to try.” Or was it just sort of, “Oh, the next time you got a letter or a call or however it happens and it just, did it just happen?”

I would say, I mean I think we were working very, very hard on improving and improving and improving the restaurant. I remember in end of 2009 after the financial crisis, we got our first four-star review in the New York Times, which is the highest accolade for the New York Times. And so we’re definitely on the track to refining things and getting better and better. And I think each year was definitely monumental in our growth, especially from where we were coming from. I mean we were a restaurant serving steak frites, eventually getting three Michelin stars and we never closed. We just changed as we were going. The moment we took the french fries off the menu, it was a big moment. I mean, we got letters complaining and telling this will be the end of this restaurant and this restaurant will go out of business because we took away the french fries. So the changes were quite monumental each year.

And I guess there are certain traditions at Eleven Madison Park, I know you recently launched Eleven Madison Home where you can sell things from the restaurant like the famous granola and which maybe might be your next french fries if you ever remove the granola. How do these little traditions get started? I’m just fascinated. How did the granola start? Of all the things you wouldn’t think that a three Michelin star restaurant would be so renowned for is it’s granola, but tell me about that.

Most restaurants of our caliber, at the end of the meal, you get something to take home, like more food. But the truth is by the end of most of those meals, you don’t really want to think about more food and you don’t want to go home and eat. Often you get a box of chocolate or you get a brioche that’s filled with butter and it’s all the things you really don’t feel like in that very moment, even though they’re very delicious. And for me it was like I wanted to come up with something that you could take home and you could eat maybe not even the next morning, but maybe three mornings from then.

But they would remind you of the experience you had. And growing up in Switzerland like muesli and granola, it’s part of my childhood. And so I thought it would be an amazing thing to create this granola that then people would take home and they can eat it even weeks after their experience and it became something people really cherish and look forward to. And people always ask us, “Can we buy it?” And for a long time we didn’t sell it, but then we decided during the pandemic that we would launch Eleven Madison Home. We’re selling the granola, we’re selling other things we’re using in the kitchen, also things we’re doing from our farm like pickles and things and spice mixes and we’re teaching certain recipes and then selling everything you need for it. But just bringing Eleven Madison Park into people’s home and make it a little bit more accessible.

(SPONSOR BREAK)

And would you say that for Eleven Madison Park that there’s a method that someone who maybe have worked for you but maybe has worked for other people as well, would say that this is the way that you put together a menu? How is the Daniel Humm way of putting together a menu?

I mean, a kitchen like ours has very high standards. We take a lot of pride in our techniques, in our craft, and so everything comes from this foundation of the craft. But then also creativity plays a big part in it. We have four principles that we use to create our dishes and when we created the dish, we ask ourselves the questions. Does this dish fulfill these four principles? And number one is, is the dish beautiful? And beauty is like we’re looking for an effortless beauty. Then, is the dish delicious? And we’re looking for a deliciousness that is instantly, when you need to think about. Was this delicious or is it not, then it probably wasn’t. It should be instant. And then the third point is creativity, because we want to add something in the conversation of culinary evolution, is there an element of surprise?

Is there a different flavor combination or is there a technique that’s used differently? And then the last one is, we want the dish to be intentional that it makes sense that it exists. And it could be as simple as a story, as two ingredients grown next to each other on a farm, or it could take a reference from a traditional dish or being inspired by an artist from another genre. So these are our four pillars. Creativity and deliciousness don’t always go hand in hand. So sometimes we really have to edit ourselves when we feel like, “Oh wow, that’s really creative, but it’s not that delicious.” So then we will throw it out and start from scratch. But even when I look outside of the plate in a way, it’s also the life I want to live. Where it’s beautiful, delicious, creative, intentional. So those aspects have actually become much more than only about creating a dish. But how do we live our lives? How do we run our restaurants? How do we create our company culture?

And speaking of company culture, the name of the company is Make It Nice, but it’s also somewhat of a motto. And I’ve had a hard time pinning down in my research exactly what you mean by Make It Nice. And is that more of an inside phrase or does it actually have a very distinct meaning for the company and the kitchen?

Yeah, when I first moved here, I didn’t really speak English and so Make It Nice was something I would just say a lot. And so this slogan became the name of our company. But then also when I think about it today, so making is very much the craft of what we do. And then the nice part is the hospitality element of it. And we always gave equal weight to both. And so I think it was a perfect name for our company because we always looked at the dining room as important as the kitchen. For the last 25 years, we’ve been making it nice, but coming out of the pandemic, we really feel that now we need to make it matter. Everything has to have a higher purpose than winning Michelin stars. And in 2017, our restaurant became the best restaurant in the world. And at that time, there really was not another award that we didn’t receive and that could feel like, “Oh my God, that’s amazing. That must feel so great.”

But the reality was, it was actually quite disorienting because we didn’t really know what is next. And it was hard to find what that next North Star is. And it took many years. I co-founded an organization called Rethink Food that was a step into the right direction, but I was personally struggling finding the next meaning because I was still very young. I am still very young. And I knew my career was going to be like another 30 years. The pandemic happened, and during the pandemic we turned in Eleven Madison Park into a community kitchen. We started cooking meals for people in need. I started getting to know New York City in a way I never did. I visited neighborhoods I never spent much time in. I connected with beautiful people. I reconnected with cooking, with food, how it can make a difference in people’s lives, how magic food is, the power of food, how it touches everyone.

And then when we knew that we were going to reopen the restaurant, which at some point in the pandemic it wasn’t clear. We were facing bankruptcy. We didn’t know how we could reopen this restaurant. We didn’t know how to pay the rent. That was for the last two years that we had no income. We didn’t know how to pay our staff. And then our landlord was really great and came to me and said, “We want to help you reopen and we’re here for you. The city needs you.” So then when I put my creative hat back on, I knew that I didn’t want to open the same restaurant as before. I knew that creatively the world does not need another preparation on a butter poached lobster or on a lavender glazed duck. So I felt like I had a responsibility to use this platform and this craft and pivot in a new direction and really explore plant-based cooking and show the world how beautiful and how magical it all can be.

And were people just thinking you were crazy for doing that at that moment? I mean, I’m curious, did you have a lot of pushback?

It really came from a creative place. I just know, I mean, you go to a dairy section in supermarket now, you’re lost. I’m lost. I don’t know what is dairy anymore or what’s not dairy or not milk or this or that. Cheese, not cheese, not cheese. You don’t know, you’re lost.

I feel better if you’re confused, then I feel a little validated.

I know! I think everyone must be lost. And with the meat alternatives and all this stuff is happening, clearly the big industrial giants have realized that we need to have another solution to feed the planet because we are actually running out of resources and the food system is collapsing. So I think the investors have realized it, the big food giants have realized it, the scientists have realized it. But what about taste? Is anyone worrying about how these things taste and how they make you feel? Are they even healthy? So I felt like, as a chef, I wanted to contribute figuring out how to bring taste to all of this. And I decided I wanted to open the restaurant as a plant-based restaurant because we have a restaurant where people come for an experience. So in my head it was like, “Well, does it really matter what it is that’s on the plate?”

It’s not like we’re selling steak and now we’re selling carrots. We’ve always sold an experience. So in my head I was like, “This is why it’s going to work.” But it was so scary. And when the reservations first went live, I didn’t know if anyone would call, and are people going to pay this price for a fully plant-based meal? And I was also not prepared for it to hit such a nerve globally. Our decision that then all of a sudden it became political, it became about climate, it became about all these things. I was not prepared. I just wanted to use my creativity. I love vegetables and I knew that we needed to put our creativity towards eating them and that was it.

And oh man, the last two years it’s been a wild ride and I’ve been criticized so much. And at the same time I was being invited to speak at the UN, at COP26 at Global Citizen. And so it’s been this mixed bag of things. Clearly it has really pushed people to have this conversation, which I’m really happy about it. But in my own industry also at times I feel like I’ve become this outsider because I think people feel like I almost turned my back towards what we were doing before and what other chefs are doing, which is not at all the truth. I just felt like we had this opportunity to make something new, to create a new restaurant.

And when you make a big shift like that, are you able to shift some of the people in the kitchen who have specific skills into now 18 different shades of working with vegetables? Is there almost like a retraining that needs to happen in terms of making such a radical shift at level?

Of course, it is creating a new language. And I think there’s a lot of fear at first that I personally had to overcome. And then every chef has to overcome and every server and everyone involved in our restaurant has to overcome and even our guests. Because at first it feels like this is going to be very limiting and we’re leaving a lot behind and we’re leaving traditions behind. And as a chef, even when you have perfected working with fish or something and now you’re only going to cook vegetables, you leave all that skill behind. At first that’s what you’re thinking. But it’s not true because all of that knowledge will help you also cooking with vegetables and what felt limiting at first today, I know it’s been beyond expanding, and I know that actually before we were limited because it is so set in stone what a meal in a fine dining restaurant is, it’s always the same proteins.

In a way we were just cooking seasonal condiments to them. One day the lobster was with lemon, then it was with rhubarb, then it was with onion. But the lobster remained, every single meal there was the lobster. Today, I feel like we’re cooking really fully entire meals, where every ingredient on the place is of this season, is off a farm and you can taste the weather and the farm and the terroir and all this, and it’s really quite poetical. So I just ate at the restaurant the other day with some friends and it was just, I highly recommend to every chef to eat in their own restaurants because it’s a very different experience when you sit down. And it just felt so beautiful to have this experience and also knowing that no life was taken to have this meal. And there’s something really moving about this. And I’ve cooked with meat my entire career, but it’s impossible not to notice that. To sit through a meal and have these pleasures and it is quite poetic. So even I felt pretty moved being in my own restaurant, having this experience.

And were you vegan before or after, personally?

I was not vegan before. I always was very much plant forward and I’m not vegan today. I am very close to it. But also what’s beautiful now, it’s like we’re taking inspiration from the entire world in a way we never have, because other cultures have actually cooked plant-based for hundreds and hundreds of years. So there’s rich culture on plant-based eating in Japan, in India, in the Middle East. And so we’re taking inspiration from a lot of different places. And when I do travel to those places, I do want to experience all the dishes that are traditional because I think for me to be creative, I want to understand it all. And yeah, I do eat meat or fish on rare occasions, but only in the moments where I feel like I get to taste something truly original or traditional.

And now, I mean obviously since sourcing ingredients is such a huge part of the game, I’m curious as the world of food has evolved and especially in the states and what people’s expectations are and what’s available. Is sourcing ingredients for you, would you say now in 2023 harder than it was maybe in 2010? Or is it easier because maybe there’s more out there and it’s easier to get things?

I think because it’s all vegetables on the plate now, I think picking the vegetables at the right moment I think has gotten much more important and crucial. During the pandemic, we started a farm upstate with a friend of mine who is farming now on six acres, just purely for Eleven Madison Park. And I think that is a great asset. For example, right now on the menu we have these sunflower hearts. He’s growing the special sunflowers where we’re eating just the hearts of sunflowers, something you can’t really get anywhere, or we’re growing celtuse or I think the farm has given us a little bit of an advantage. Because I think we don’t want to just give you carrots and celery and fennel and all the things you know, but we do also want to bring you some elements of things you maybe have never seen before and that are surprising.

What’s maybe the most surprising or exotic plant that you’ve brought in so far?

We work with almost only local ingredients, but during the pandemic we worked with a Zen Buddhist monk. Because the Buddhist cuisine called shojin is very, very old and it’s fully plant-based. And it’s also a ritual of eating in a Buddhist temple and it’s really poetic and really beautiful. And so I knew that in fact, it is the original Japanese cuisine. This is where the kaiseki cuisine was born out of, that was completely plant-based. Only in recent years has been meat and fish added. And so we have one ingredient in the restaurant that is from Japan that we’re getting from Japan, and it’s this called tonburi, and it’s the seed from the cypress tree. And it’s this beautiful ingredient that we cook in a pressure cooker with seaweed, but it just has this beautiful texture and it’s just been really exciting to explore so many different things.

And you have your first ever art book coming out called Eat More Plants. And I’m wondering why an art book and tell me about what it’s like. What can we expect?

Yeah, I’ve been asked so much about this question, how it all happened to go plant-based. And it’s hard to give you the answer in one sentence or even in more sentences because it didn’t happen overnight. It happened over time. Clearly the pandemic made me have the courage to do it, because during the pandemic I felt like I was almost losing everything. I didn’t know if there ever is going to be Eleven Madison Park again and we’re facing bankruptcy. And from that place making this decision felt like, “Well, we had nothing to lose, let’s try something else.” But during the pandemic and even my entire career, but I always keep journals and in my journals or drawings and I paint with the oil and I take notes.

But during the pandemic it was all about the theme of vegetables and the fears of opening, the fears and possibilities as well. There was fear and hope and dream and I wrote the journal, or I kept the journal during the pandemic and I had this amazing publisher from Germany visit our restaurant. His name is Gerhard Steidl, and he’s published some of the most important art books of Richard Serra or Joseph Beuys or Ed Ruscha or Roni Horn. And he came to the restaurant and he was really moved by the experience. And then he asked me about my creative process and how I work. And I said, I journal and I paint and I draw. And he asked me if he could see it.

And sure enough, the next morning he showed up in my office and wanted to see my journal. And my journal I’ve never shared with anyone because it’s so personal. And so I felt nervous about it. It’s also not an art book, this is just my journal to be clear. This was never even meant to be shared with the world. But then he saw it and he really loved it and he encouraged me to make a book together. And so then I went to Germany and I went there for a few weeks on two trips and we created this book. But it’s really publishing my journal. It’s the most intimate personal look into the earliest days of having this idea.

And I’m wondering when people were quite critical of the shift to a vegan model and then later on when you had so much success, did you have other chefs or restaurateurs reach out to you to say, “How did you do it? Or how do I convince my boss to do this? Or the person who owns my restaurant, how to make that shift?”

I don’t think we have quite gotten there. I think I do see that our move has definitely changed things. I think it has allowed more other restaurants to have more plant-based options. Like now when you go to a coffee shop, almost every coffee shop here in the area, their default milk in a cappuccino is oat milk. That didn’t happen a year ago. That really recently happened. And so when I start seeing these differences, I do know that we are part in this, I’m not taking credit for this, but we are part of this movement that is quite powerful and hopefully we’re gaining more and more mass.

I think within my own industry and that’s been challenging for me because I think my industry felt maybe threatened in some ways. I know that people have talked behind my back and probably are happy when we get a bad review. And because I think if this path eventually is going to work out, then I think it’s going to put a lot more pressure on other restaurants to change their ways also. And change can be scary and I understand that. So it’s almost like, for the moment, I think I’m very much an outsider and it feels like I maybe turned my back on my industry. Which is not at all how I feel, but I understand how people can see it that way.

And when it comes to this shift in thinking, what vibe are you getting from young chefs that come to you and cooks and sous chefs and people like that that want to learn from you? Do they come, do you think that they are just out of the gate, maybe a little bit more knowledgeable than you were in the beginning of your career? How are these young chefs, are they a different class of, do they understand food in a different way than maybe you did?

A 100%. I mean, that’s what’s so encouraging. I think it is, well, plant-based eating is the future. This is not a trend. This is not going away. We have to change the way we eat. We have to reduce how much meat we eat. And I say this all the time, but we’re not anti-meat, but we are pro-planet. And seeing the young generation worry about the planet and their future, I think they’re much more on board with this idea and they celebrate it. And even our customers, the age of our customers has gone down tremendously and it’s beautiful and the guests are more diverse and are more question things and are more knowledgeable in some ways even. And no, I think we’re right there.

When you make a change, you want to be one step ahead, but you don’t want to be two step ahead because then you miss everyone. And I think we’re right between, on some days we’re right one step ahead where we want to be. And then on other days we maybe are a little bit too forward-thinking. But I think we’re right there. And I think the mass around this is building, the excitement about plant-based eating is building. And by the way, this future is amazing. It’s more beautiful to eat plant-based. It’s more creative, it’s healthier, it’s all these things. We’re not leaving anything behind. We don’t need to be sad about it that we’re not eating pork and duck and all these things anymore. And even if we eat it sometimes, we’re also saying in such a changing world that’s changing so rapidly, I think it’s really important that we celebrate change even though we don’t get it perfect every step of the way, but change is necessary and it’s about progress and not perfection.

I was invited to speak at Nike, the Sustainability conference. And Nike, by the way, is such a tremendous company and they’re so forward-thinking and sustainability is central in the creativity from day one. I mean, it’s just so inspiring to be there. But they don’t even talk too much about it because aspects of their company is not as sustainable as it could be. So if they’re talking about sustainability, then the naysayers come and take them down and say like, “Oh, Bob, what about here? Or what about that, or what about this?” And I think that’s what’s a little bit broken with our world that we are not celebrating change. We are more looking for faults. And I think we definitely experienced this. For example, at the beginning we have a restaurant and then we also have a private dining room. And our private dining we also have a business that we need to run.

And if we actually don’t have customers, then our whole idea is going to be meaningless and will not matter at all. If our restaurant closes, all our plant-based talk will not be important at all. No one will remember. So of course when we reopened, we knew we’d take a big risk, but we also wanted to limit our risk in some ways. And in our private dining room, we also had certain events from pre-pandemic. And so we said, “Let’s start in the restaurant and let’s go all the way in the restaurant, fully plant-based, no animal product, but let’s in our private dining room, let’s don’t change yet. Let’s see how this is going.” And sure enough, we reopened the restaurant and after two weeks people came at us and said, “Oh, but what about in the private dining room?”

And yeah, it’s complicated and we’ve been weathering the storm and thankfully it is being successful. And thankfully we have transitioned our restaurants all to plant-based eating. But the future restaurant might not be a 100% plant-based, it might be just much more thoughtful. It might be plant forward. Like for example, oysters. Oysters are not harmful to the environment. So maybe oysters are okay. Maybe there is some incredible trout farm that everything is sustainable, and maybe that’s okay. I think the future will be close to plant-based, but somewhere in the middle. But at Eleven Madison Park, Eleven Madison Park has never been your average restaurant. It has always been the pinnacle to something. So we just felt like to go all the way with this platform was the right way. But I think it’s probably always somewhere in the middle. It’s never the extreme.

And I guess now that you’re a plant-based, any french fries? Had the french fries made a return?

Well, not on our menu, but I have to say a french fries is a guilty pleasure. A good french fries is very, very satisfying.

Thank you to our guest, Daniel Humm and to Becca Parrish and everyone at Eleven Madison Park for making this episode happen. The editor of the Grand Tourist is Dan Hall. To keep this going don’t forget to visit our new website and sign up for our newsletter, The Grand Tourist Curator at thegrandtourist.net. And don’t forget to follow The Grand Tourist on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you like to listen and leave us a rating or comment. Every little bit helps. Til next season!

(END OF TRANSCRIPT)

The newest gallery openings this week, including the dark side of the American dream, traditions of Aboriginal Australian painting, a cheeky photographer, and more.

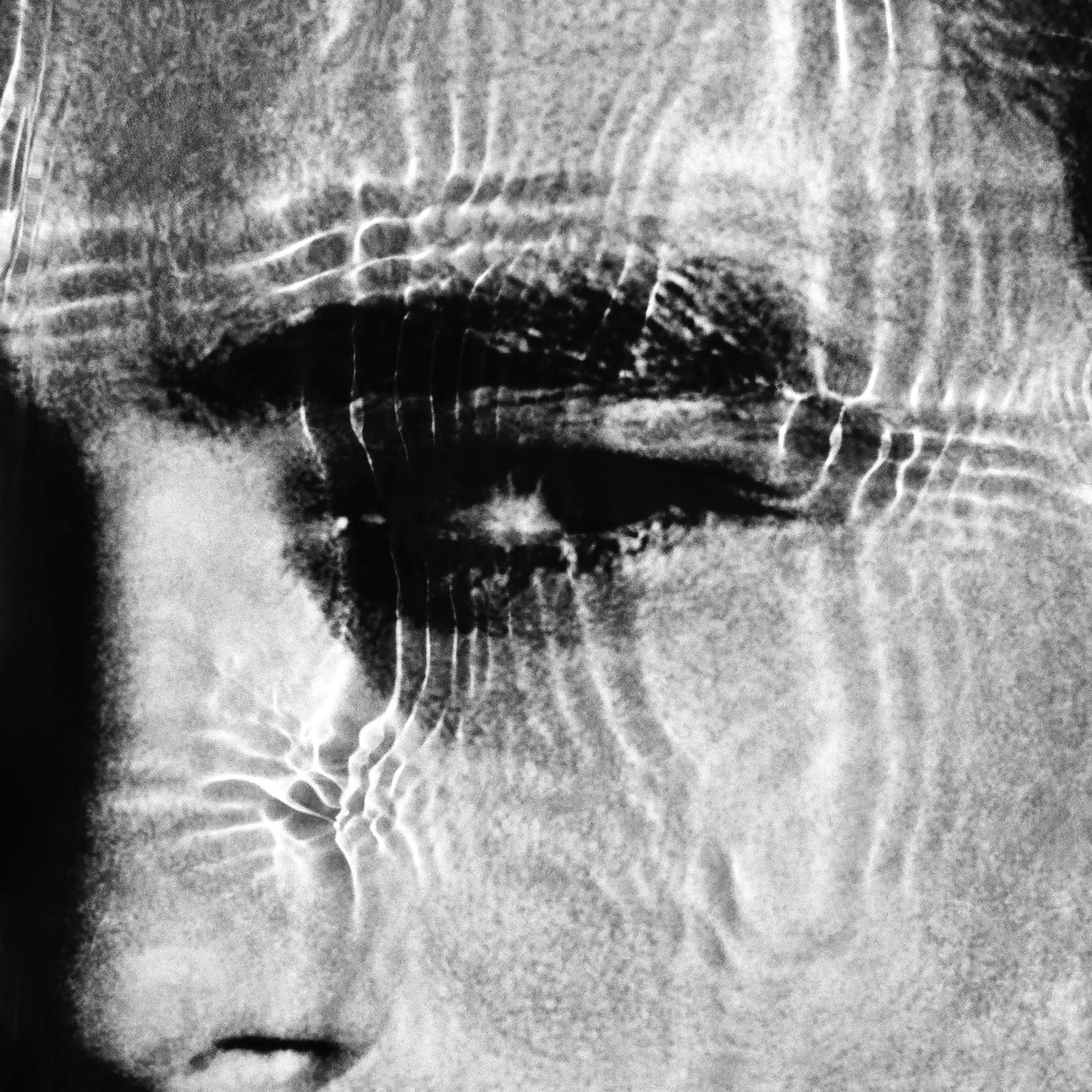

For Italian fashion photographer Alessio Boni, New York was a gateway to his American dream, which altered his life forever. In a series of highly personal works, made with his own unique process, he explores an apocalyptic clash of cultures.

Plus, an exciting young British artist receives a retrospective, Marcel Dzama's whimsical drawings take a political turn in L.A., and more gallery openings.