Mark Your Calendars: The Grand Tourist 2026 Guide to Art and Design Fairs

A great design or art fair sets the tone for the year, defines the conversations, and points to where taste is headed. These are the fairs defining 2026. Save the dates.

Welcome to The Curator, a newsletter companion to The Grand Tourist with Dan Rubinstein podcast. Sign up to get added to the list. Have news to share? Reach us at hello@thegrandtourist.net.

There can’t be many pieces of furniture design that have been in continuous production for 60 years, their star never fading over time. The Dezza armchair, by the inimitable postwar Italian designer-architect Gio Ponti, is one such piece. This year, Poltrona Frau—for whom the Dezza was designed in 1965—is set to mark its anniversary in style, with a striking edition of 60 that showcases a set of distinctive, newly uncovered drawings by Ponti. The Dezza has become something of an emblem for the Italian furniture brand. Conceived for the new Poltrona Frau HQ in Tolentino when Ponti was 74, it takes its name from the address of a building he had designed and was living in on Via Dezza in Milan. Ponti never liked to be styled as a Modernist, and he certainly didn’t believe that form follows function, but the Dezza’s refined silhouette—from the boxy structure to the gently curved armrests and tapered legs—was unmistakably modern and pioneering, as was the consideration toward its efficient manufacturing.

“It summarizes some of Ponti’s most important design principles,” says Poltrona Frau CEO Nicola Coropulis, “both from a formal perspective, as seen in the characteristic tapered triangular leg, and from a methodological standpoint.” The Dezza, it seems, streamlined production by limiting the number of parts required, simplifying assembly. The armchair’s celebratory new clothing is suitably arresting. The upholstery is a powerful blue shade of leather, called Iris, and is used across the armrests and color-matched in the lacquer that coats the legs. The seat, meanwhile, is covered in Panna leather, digitally printed with Ponti’s as-yet-unseen drawings of hands. The colors of the upholstery were chosen to conjure the sunny Mediterranean tones that Ponti used in his design of the Hotel Parco dei Principi in Sorrento, and the quirky hand drawings, which were acquired at auction by a collector known to the heirs of Gio Ponti, who run the archive, were chosen to shine a light on Ponte’s figurative artwork, as a change from his more familiar geometric motifs. The illustration features 26 stylized hands, each carrying its own guise and name, from the Gloved Hand to the Flowery Hand and Rotating Hand. They recall the famed ceramic objects (modeled on glove molds) with which Ponti revived the Ginori 1735 brand when appointed creative director in the 1920s. There’s no doubt that hands were a significant, repeated theme throughout Ponti’s career. “With our re-editions, we always try to deepen the cultural significance of the original design,” says Coropulis. “This collaboration honors the legacy of Ponti, but also enriches the narrative surrounding this icon.” poltronafrau.com —Emma Moore

Sculptors With Cameras; When Rauschenberg met Twombly; and More Art Around the World

New York, “Photographer as Sculptor, Sculptor as Photographer” (Until June 7)

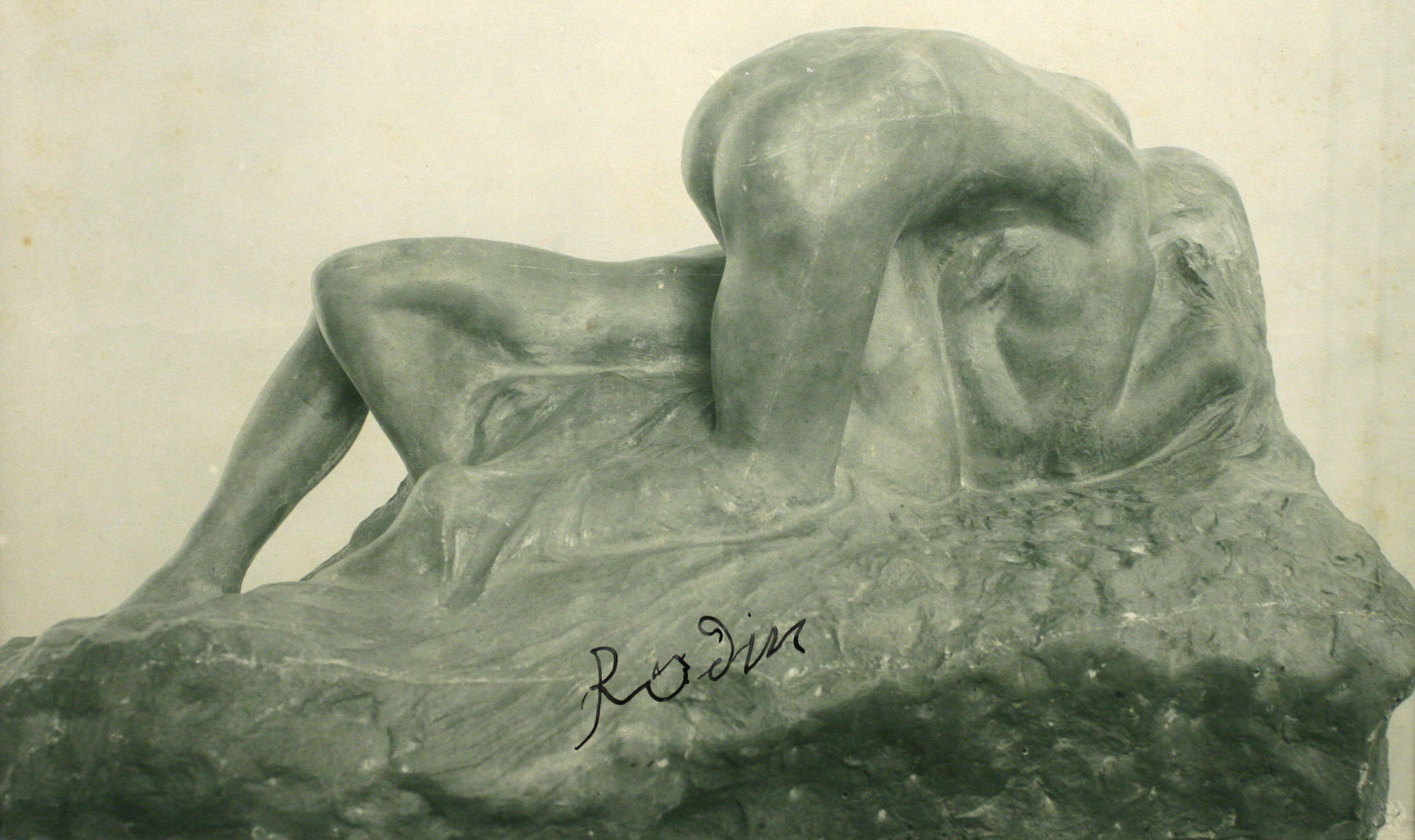

In the late 1800s, an intense debate was taking place within France’s Academy of Fine Arts: should a photograph be considered a form of honest documentation or a work of art? The French sculptor Auguste Rodin initially subscribed to the former belief, only using photography to objectively document his work. However, Rodin soon began experimenting with light and angles, making photographs an extension of his sculpture and eventually even exhibiting the two together. Later, sculptors like Constantin Brancusi, David Smith, and Henry Moore also used photographs to play with the appearance of their work. And vice versa: In the photographs of Bernd and Hilla Becher, industrial structures become sculptures. Bringing together the work of some of the most influential artists of the 19th and 20th centuries, this exhibition poetically blurs the line between the two art forms. brucesilverstein.com

London, “Richard Wright” (Until June 22)

Turner Prize winner Richard Wright almost quit painting before discovering his practice. An art school graduate, the British artist was painting traditional figurative works through the late ’70s and early ’80s. In 1988, he stopped and destroyed all his work. “I became disheartened,” he later said. “Disheartened by painting one bad painting on top of another.” He began sign painting to make money, which proved to be a sort of palette cleanser. Inspired by the realization that paint didn’t have to “pretend to be something else,” Wright would soon start painting directly on the wall. He’s known for these large-scale works, like 47,000 stars painted on the ceiling of Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum, that expand the limits of painting. For his largest UK exhibition of the last 20 years, a new site-specific painting is accompanied by 50 works on paper, glass, and 3D objects from his 30 year career. camdenartcentre.org

Munich, “Five Friends: John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Cy Twombly” (Until Aug. 17)

The friendship between these five artists helped define post-war art. In the summer of 1951, musician John Cage, choreographer Merce Cunningham, and the painters Robert Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly met at Black Mountain College in North Carolina. The four quickly connected, and in 1954, the painter and sculptor Jasper Johns joined them. Their discussions and collaboration both in the studio and on the dance performances of the college’s Merce Cunningham Dance Company would have significant impacts on music, dance, painting, sculpture, and drawing. This exhibition examines the reverberations of this consequential friend group with no less than 180 works of art, scores, stage props, costumes, photographs, and archival objects. museum-brandhorst.de

Paris, “Roots of Heaven” (Until June 2)

“I’m trying to erase the notion of time and place,” said French photographer Julien Drach in an interview following Sotheby’s exhibition of his series Roma in 2022. The series, begun in 2018, was Drach’s attempt to capture the memories lurking in the walls, weathered statues, and eroding paint of the city. Drach’s continued fascination with history has taken him and his camera to Pompeii and Athens. His images aren’t your typical tourist shots. For one, a conspicuous lack of people gives them a dramatic stillness. In this show, fifteen of these black and white Polaroid films present the haunting beauty of the ancient ruins. annesophieduval.com —Vasilisa Ioukhnovets

A great design or art fair sets the tone for the year, defines the conversations, and points to where taste is headed. These are the fairs defining 2026. Save the dates.

We assembled our favorite design objects for the people on your list that have everything, including taste.

We checked in with our former podcast guests who will be inching through Miami traffic, unveiling new works, signing books and revealing new projects this year.