Mark Your Calendars: The Grand Tourist 2026 Guide to Art and Design Fairs

A great design or art fair sets the tone for the year, defines the conversations, and points to where taste is headed. These are the fairs defining 2026. Save the dates.

Welcome to The Curator, a newsletter companion to The Grand Tourist with Dan Rubinstein podcast. Sign up to get added to the list. Have news to share? Reach us at hello@thegrandtourist.net.

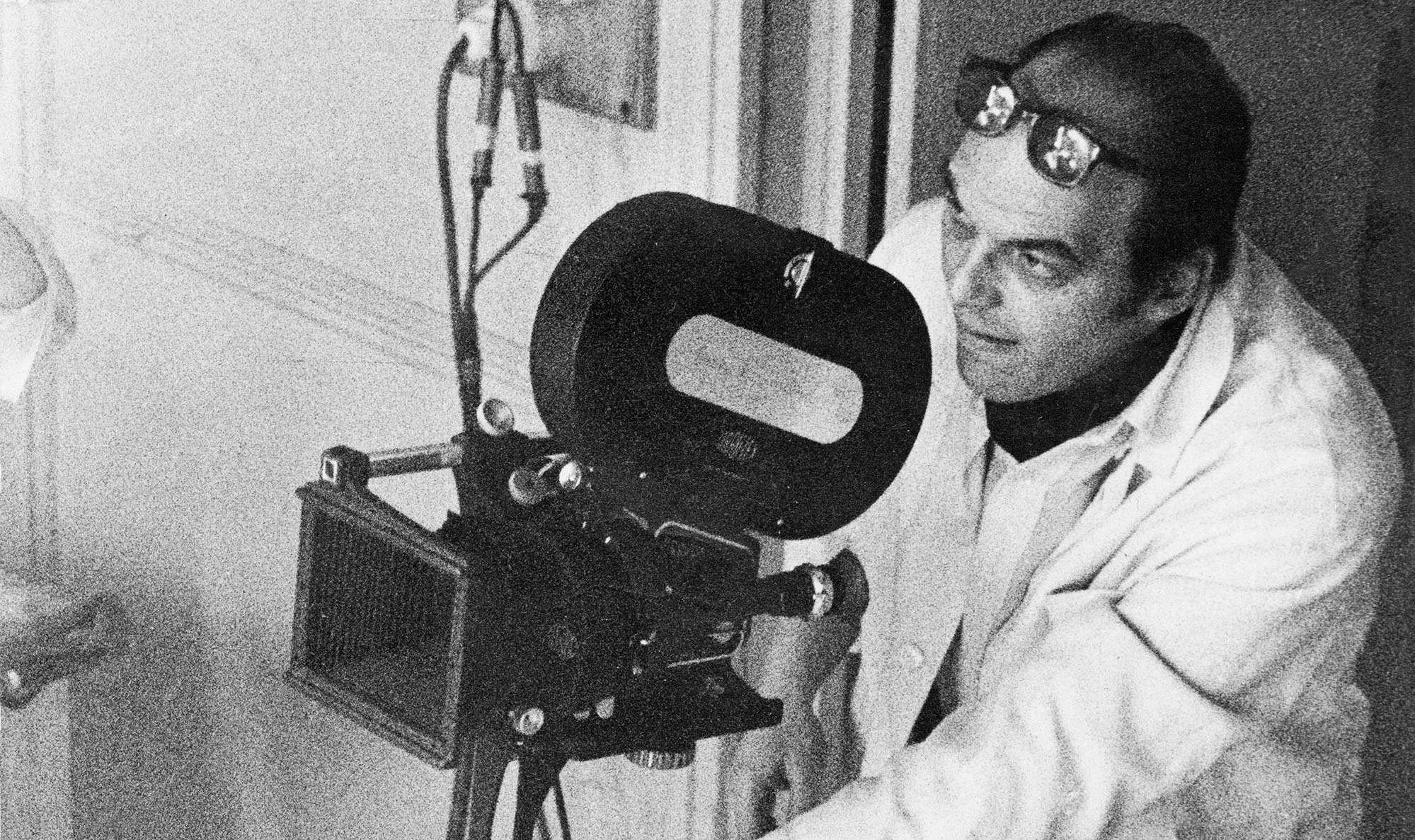

Despite the lack of a renowned byline, the work of photographer and filmmaker Tom Kublin is legendary. His stark black-and-white portraits of resplendent haute couture gowns are instantly recognizable. Throughout his short yet prolific career, Kublin captured numerous couture collections of the ’50s and ’60s—Givenchy, Dior, Chanel, Yves Saint Laurent—but developed a special relationship with one in particular: Cristóbal Balenciaga. “Balenciaga–Kublin: A Fashion Record” (Thames & Hudson) is the first book to catalog his work. And as its title suggests, the tome celebrates the symbiotic match between designer and photographer.

Balenciaga was renowned for his mastery of the silhouette—shapes we now consider commonplace—and Kublin’s spare, often monochromatic photography style allowed the eye to travel along the curvature of a cape or the balloon of a skirt in an uninterrupted fashion. “Kublin really helped him to build this image for the brand,” says fashion curator Ana Balda, who helped Kublin’s daughter, art and photography curator Maria Kublin, to assemble the more than 140 photographs that make up the book. It all follows an exhibit at Spain’s Cristóbal Balenciaga Museum: “Tom Kublin for Balenciaga: An Unusual Collaboration.”

The book also features excerpts from Italian fashion photographer Gian Paolo Barbieri, editor in chief of “Harper’s Bazaar UK” Lydia Slater, and Kublin’s partner and muse, model Katinka Bleeker. Most of all, it’s a visual ode to an artist who made a lasting imprint on the industry. Ahead, Maria Kublin and Balda discuss the process of curating the book, the magic of the relationship between designer and photographer, and the manner in which Tom Kublin could breathe life into a gown. —Camille Freestone

There was an exhibit that preceded this, but how did you both decide to turn that into a book?

Maria Kublin: We always felt it needed a catalog, something tangible. You cannot expect people to come to Getaria just to see an exhibition.

How did Balenciaga’s and Kublin’s aesthetics complement each other?

Ana Balda: I think that is the key question. When Balenciaga met Kublin, it was the mid-1950s. At the time, the trends in fashion photography were diluting the art of couture in the images. It was more focused on the ambience, the locations, the beautiful models. I think that Balenciaga saw in Kublin something young and new without being influenced by all these trends. Something that might help to construct the image of the brand based on the art of couture: the technique, the beautiful dresses, the creations.

MK: I think that there was a sort of mutual understanding. My father was very classic. He thought it was really important to shoot in a studio because there was no distraction. He didn’t need flashy things in the background. He was a master at bringing out the best of a garment. They understood one another. It’s a difficult thing to explain.

What was the process of curating the book like?

AB: We continued the line we opened for the exhibition. We did a lot of research in different archives, and we collected a lot of Kublin’s photographs that were previously unknown.

Where did you look?

MK: The main source was the “Harper’s Bazaar” archive, both from the UK and the U.S. The archive of Balenciaga in Paris was also a very important source. I still come across images that I didn’t know were taken by my father—like some of the Schlumberger jewelry. There were pictures of his in a museum I had never seen—an underwater scene with this beautiful necklace. In the ’50s, a lot of work was not well credited, so I still come across work that I feel must be my father’s. It’s interesting to see something in his style and think, “It looks really Kublin.” It’s a road that we are just starting to walk, and it’s not ending anytime soon.

What did Kublin’s career look like outside of Balenciaga?

MK: My father worked a lot for Givenchy. He worked for Dior, Chanel, Yves Saint Laurent. I’m in touch with the curators of the Yves Saint Laurent Museum in Paris. They showed me this letter that Yves Saint Laurent wrote to my father, thanking him for his beautiful work, et cetera, et cetera. And that he thought of him very highly. I also came across a letter from Diana Vreeland, who did a Balenciaga exhibit at The Met in 1973. The letter says she really wanted to have the photographs and the films by Kublin in the exhibition. I have come across so much information like that. So it’s not only Balenciaga, it’s so many big names from the ’50s and ’60s.

Are there any photos from this collection specifically that stand out to you?

MK: For me, that’s very easy. It’s the image with my mom, who was a model, where she wears a big black hat. They met each other in New York. On a personal level, it means a lot to me. She’s beautifully photographed by him. My mom has worked with Avedon and Hiro and Helmut Newton, but she always said she felt a bit like a doll. With my father, she also had a bit of input. It was something they worked on together. So knowing that makes it even more special for me.

Maria, what was it like to interview your mom for this?

MK: It was interesting. A lot of people have asked me how she feels about me reviving the legacy of my dad. She says it was a long time ago. She was young and beautiful then, and this is now. Nowadays, if I show her old images of herself on Instagram, she’s like, “Oh, that’s quite nice.” If it’s about her, she comes alive. It was nice to ask her questions, especially since she’s now 85. It’s interesting to learn from her not as a mother, but as a working model. You assume a lot of things, but really asking a question about it and hearing the answer? Well, that’s a completely different thing.

Now looking back on the curation of this collection, how would you summarize the significance of these photos?

AB: I would say that Kublin really built the image Balenciaga wanted for his brand, because Balenciaga has remained as a classic in the fashion world. I think that Kublin’s perspective is a key piece in the building of his image, because Balenciaga had a very clear vision for the brand.

MK: It’s a visual dialogue. He allowed Balenciaga to see his work from a different perspective. Balenciaga could see photographs and notice new lines or have lighting illuminate something interesting. I think you can learn from each other and grow in the process. They were taking each other to a higher level, perhaps. I cannot ask them, obviously, but I think that might have been the case. It’s a beautiful development.

The Surprising Elegance of Steel; Remembering an Extraordinary Librarian; Frank Lloyd Wright’s Unseen Photographs

Cambridge, “Steina: Playback” (Until Jan. 12)

In 1971, Steina and her husband, Woody Vasulka, founded The Kitchen, a place for showing videos and performances in the kitchen of the Mercer Arts Center in New York’s Greenwich Village. Still around today as a nonprofit art collective, it started as an outlet for the pair’s experimental video art. Steina, who has a background in classical violin, emigrated from Iceland to the city with her husband in 1965. She became involved with the local art scene and was fascinated with editing audio and video into dizzying, mind-boggling creations. Her first retrospective in over a decade presents a range of her early videos with Woody and later independent videos that play with perspective and sound. listart.mit.edu

Chicago, “Photographing Frank Lloyd Wright” (Until Jan. 5)

Architect Frank Lloyd Wright understood the mutual relationship between his iconic structures and photography, which allowed the often distantly situated works to be publicized. He dabbled in the art form himself, too, purchasing his first camera in the late 1800s and using it to capture a trip to Japan, landscapes, family, and self-portraits. This is the first exhibit to show Wright’s early photography and explore his collaboration with the photographers of the iconic shots featured in “Life” magazine and “Architectural Forum.” driehausmuseum.org

New York, “Sean Scully: Duane Street, 1981–1983” (Until Feb. 1)

In 1811, New York City’s booming population inspired planners to implement the grid system. The city was divided into blocks, narrowing the movement of carriages and pedestrians to straight lines and right angles, thus birthing the city as we know it. About 170 years later, in a not-yet-fashionable Tribeca, Sean Scully was painting enormous horizontally striped panels in his breakthrough body of work. “They are very ‘New York’ paintings,” wrote “Time” magazine. “The city they evoke is not the foreigner’s imagined grid of perfect planes; rather it is gritty, heavy, slapped-together lower Manhattan, where Scully has his studio: the hoardings of warped plywood, the metal slabs patching the street.” The groundbreaking 11-panel work titled “Backs and Fronts,” exhibited at MoMA PS1 in 1982, will be presented in this exhibit with seven others made at the Duane Street studio. lissongallery.com

New York, “Precious Strength: Maria Pergay Across the Decades” (Until Nov. 30)

In the Paris of the late ’50s, female designers were often written off as “decorators” compared to their male counterparts. It was then that Maria Pergay, a mother of four with a degree in costume design, began her career designing furniture. She was radical in her affection for stainless steel, an arguably austere metal, but out of which she could coax softness and elegance. To the Parisian émigrée, “nothing is more beautiful than steel.” The late designer was little known in the U.S., but by the ’70s, she had designed interiors for the president of Tunisia and completed commissions for the empress of Iran. This show presents work from her entire career, including early decorative objects and her iconic Ring Chair, inspired by an orange peel. demischdanant.com

New York, “Belle da Costa Greene: A Librarian’s Legacy” (Until May 4)

Her name is probably unfamiliar, but she was a critical figure behind the beloved Morgan Library & Museum in New York. In 1905, Belle da Costa Greene was hired by J.P. Morgan to be his personal librarian. Through her expertise and deft negotiation, she amassed his exceptional collection of rare books and manuscripts. When the collection became a public institution (celebrating its centenary this year), Greene was appointed as its director. But Greene herself is shrouded in some mystery, partly because she burned her diaries before her death. This is the first retrospective examining her remarkable life, as a masterful librarian and white-passing Black woman in segregated America. themorgan.org —Vasilisa Ioukhnovets

A great design or art fair sets the tone for the year, defines the conversations, and points to where taste is headed. These are the fairs defining 2026. Save the dates.

We assembled our favorite design objects for the people on your list that have everything, including taste.

We checked in with our former podcast guests who will be inching through Miami traffic, unveiling new works, signing books and revealing new projects this year.