Christine Ay Tjoe’s Abstractions Look Inward

Plus, an exciting young British artist receives a retrospective, Marcel Dzama's whimsical drawings take a political turn in L.A., and more gallery openings.

This artistic icon is something of a graphic design daredevil. Or perhaps a prophet. Through his wildly inventive works, he challenges conventions and communicates ideas that can alter the way we perceive society. On this episode, Dan speaks with the legendary creative on his latest book, “Now Is Better,” why he’s much happier than his documentary, “The Happy Film,” suggested he is, and reflects on his successes and admiration for book publisher Phaidon that is celebrating its 100th anniversary.

For more information about the 100th anniversary of Phaidon, and its recent exhibition at Christie’s auction house in New York, you learn more here and even shop the installation.

To watch Sagmeister’s 2016 documentary, “The Happy Film,” you can watch the film on Amazon Prime, iTunes, Vimeo, and Google Play.

TRANSCRIPT

Stefan Sagmeister: It has to do more than just function because if you just pursue functionality, the things don’t function very well. You also need, I don’t know, delight or beauty or something on top of that that ultimately will make it work much better.

Hi, I’m Dan Rubinstein, and this is The Grand Tourist. I’ve been a design journalist for nearly 20 years, and this is my personalized guided tour through the worlds of fashion, art, architecture, food, and travel, all the elements of a well-lived life.

My guest today can best be described as a graphic design daredevil or maybe a prophet. Through his creations, exhibitions, books, artwork, products, topography, murals, installations, album covers, and even films, he doesn’t only create things for his clients to help them communicate, but he uses craft to espouse his own ideas about life, work, and the world around us, Stefan Sagmeister. Sagmeister got a start in the industry at an early age, creating a magazine for a left-wing organization in his native Austria, and later studied graphic design in Vienna before studying at a scholarship at Pratt University in New York.

After working for others, he started his own agency in the early ‘90s. He’s created album covers for the likes of David Byrne, Lou Reed, and The Rolling Stones, identities for institutions like the Jewish Museum in New York, and various campaigns, posters, and lots of books. He’s probably best known for his innovations in typography, specifically creating his messages in the real world and then photographing them in various ways. He might draw letters on the petals of flowers or even etch words into his own skin. He’s also known for a deliberately non-commercial savvy way of working. He divides his career into these seven-year spans often changing firm partners each time and taking a year off in between to work on personal projects that never see the light of day. If you’re a fan of the logo of this very podcast, you can thank one of his early partners, Matthias Ernstberger, who’s also my cohort during my days editing Surface magazine.

Hi, Matthias. These phases of Sagmeister’s career can also have themes. His latest is Now is Better, a project that is culminated in exhibition in various works, including one of his groundbreaking books. One of his favorite partners in publishing is Phaidon, which just celebrated its 100th anniversary. And we’ll speak with both Stefan and the brand’s group publisher, Deborah Aaronson, later in the program. I’ll admit, after watching his 2016 documentary simply titled “The Happy Film”. Where he’s followed around by cameras just trying to be happy, I was a bit nervous. Spoiler alert, in “The Happy Film,” he doesn’t quite come across as a happy guy. Luckily for me, he turned out to be happier than most, and I find his insights into the real world and how it mixes with creativity to be totally endearing and riveting, and it’s all mixed with a bit of Austrian matter-of-factness.

I caught up with Stefan from his studio just a few blocks away from me in New York to talk about getting along with his teachers in school, the fallout from his happy film, where the personal and professional parts of his life collided, and why he thinks life now is better than ever before.

(MUSICAL BREAK)

So, part of the mythology of your early life was that you worked at a magazine when you were something like 15 years old, and it was perhaps a left-leaning magazine. Can you tell me a little bit about how you got working on that and what we would consider not a legal age to be working?

Well, this was a small magazine. It was a magazine for Arlberg, which is the county or the state that I’m from, the best part of Austria, close to Switzerland and Germany. And this was a youth magazine, left-wing, as you mentioned, and I had changed schools. I was very unhappy in an engineering type of high school and changed back into a regular high school where I was much happier with and I was aware of that magazine and I saw not one, I saw a boy not from my class but from another class who had a sticker of said magazine called Alphorn on his bicycle. And I talked to him and he said, “Well, the magazine actually meets in the basement of his house,” and I should just come by on Monday evenings, which I did. And I wrote a couple of articles stand for that magazine, not very good ones. I was very aware that the other writers, they were significantly… but they were also a bit older, but they were significantly better.

And when the person who was sort of responsible, it was always a joint effort but who was responsible for doing the layout moved to Vienna to study, that, I don’t know, that job became open and I tried my luck at it, and it turned out that I really enjoyed it. I was not bad at it. And probably most significantly, the magazine was involved in all kinds of cultural avenues like organized a music festival, did a demonstration here or contributed to some protests. All these sort of things that ultimately needed graphics. And considering I already did the layout, then that was also up to me if I look back on it, most of that was very amateurish. We also had no money so I found that we got the Letraset sheets, which were popular at the time, to make headlines. You rub them off a piece of Valium, we got them donated by design studios close by, and all the Es were always missing because that’s the most popular letter in German so be…

I found out quickly that completely drawing the entire headline by hand was actually more efficient than recreating painstakingly the E that was missing. And my guess is that that probably had some sort of influence on my designs much, much later that did feature a lot of hand-drawn elements.

Yeah. To be resourceful in a sense.

I think that that’s part of it. But I think what was incredibly valuable at the time was that you did something, you designed something and it had a visible effect. You put a poster up for a concert, and that was the only thing how people would know about the concert and 300 people would show up. And so this deep understanding of function in me. Never really in the studio when sometimes students that I talk to are incredibly surprised by this. All of the things we’ve ever done in the studio had functionality very, very much in mind, meaning that it was throughout the process from the beginning until the very end of the execution, how this would ultimately work was foremost on our mind. But of course, that ultimately is not enough. It has to do more than just function because functionality… If you just pursue functionality, the things don’t function very well. You also need, I don’t know, delight or beauty or something on top of that that ultimately will make it work much better.

And in your book, which we’ll get to soon, you tell a story about your father who grew up in rural Austria and some of the local legends there. And I was wondering what your parents were like and how they kind of, what they did for a living or how they kind of influenced you as sort of a young magazine editor even?

Well, I grew up above a store. My parents had a clothing store.

What kind of clothing?

At the time when my parents had it was very much usable quality clothing. So it was the big store in the small town. Bregenz where I come from, it’s a pretty small town with 25,000 people. It was the biggest store in that town. So my parents were known in town, and it was the place where you bought your work clothes if you wanted quality work clothes, but also your suit for Sunday church.

Oh, okay.

It was not fashionable really. It was about quality and it was about the kind of clothes that you actually needed. I think a lot of my parents’ clients bought a new suit when the old one wasn’t repairable anymore, that sort of thing. And they took over the store from their parents, and those parents took over the store from their parents. I think it’s 1780 when the store was started. And in the beginning it was sort of a mixture between antiques, but very low level antiques. So you could also say it was kind of crap plus antiques.

Yeah, no, I think I… And kind of probably like a general door maybe in a sense or?

Yeah, and the area that for Arlberg, which is now extremely wealthy, maybe one of the wealthiest areas in Austria, and definitely everybody is doing well in the 18th and 19th century was incredibly poor. So of course an antique store had extremely low level kind of quality works, that sort of thing. And even we’ve actually at one point designed the identity for the local museum. When I talked to the director, he said the collection is unbelievably poor. Because the money was in nearby St. Gallen in Switzerland or in Munich or in Bavaria, but for Arlberg was just poor. Meaning to the point where even in the beginning of the 20th century, kids had to be sent to southern Germany to be fed because the families in Freiburg were not really able to feed their own kids.

Oh gosh. So do you think, were your parents kind of conservative growing up in that sort of mentality, in a sense?

I mean, they would definitely be voting for the conservative party, but then the entire county vote. Basically this is a conservative part of Austria, not so much anymore where it’s quite forward-looking and quite modern. I mean, in Bregenz there is a museum of contemporary art that is as good as anything you would find in New York City, with extremely high level program built by a fantastic architect. Meaning if this building with its program would stand in Chelsea, it would be a complete hit.

(SPONSOR BREAK)

And as someone who, I kind of feel like your work routinely tries to break conventions in some way and speak a bit about design culture and design criticism, or at least confront it in a way. I’m wondering as a student, you went to school for design, you came to New York on a scholarship, you went to Pratt. Did you get along with your teachers? Your design teachers or your art teachers in school, or were you kind of chafing against maybe some of their orthodoxy?

I was. I mean specifically in Austria, I went to the school ultimately that I wanted to, which is the [foreign language 00:14:39] mean University for Applied Art. And the graphics program at the time was run by a professor who sort of had lost his team by the time we had him. He was elderly and I felt by that point had kind of given up. He wasn’t really informed on what’s going on digitally. And it was a very conservative program, meaning we still learned to paint set typography with brushes. So we literally would paint Times New Roman, but not just a headline but we… Meaning not a lot of text, but entire sentences with design, painting them in a brush if we needed them in a color, because that was the only way that that saw the faculty would know how to do that. And at Pratt, it was much more of a mixture where I think I would rebel against some professors, but was very much in favor of others.

And at the show that we just had in Tribeca, three of my favorite professors actually showed up at the opening from Pratt. And we loosely had stayed in touch. And there was definitely this, meaning it was also a much more professionally one program I would think. So in Austria as in Germany, the universities in the arts or in design run a masterclass program where you would be the entire four years with one professor, which can be fantastic if the professor is great and not so good if that is not the case.

Right. And after school, you had a few different jobs in different places before striking out on your own. And I was wondering if you recall when you went out on your own, what your first commission was that kind of A, was just sort of your first big break as an independent studio, but also one that might have solidified in a way what would become your process? Or did you have it at that time or did it take a little bit for things to kind of settle?

Well, after school I worked in Hong Kong quite commercially for two years, then for my favorite studio in the world M&Company with Tibor Kalman for quite a short while, for six months before I opened my own studio. And the idea really was to keep the studio small and to do design for music. Because that’s really ultimately what my old dream was as a 15-year old when I worked for the little magazine to do album covers, which at that point were of course just transformed into CD covers. So I just came in at that time and that’s what I would be looking for. And I think my first CD cover commission was by a New York underground band where the singer was Austrian and whom I know, and this was a band called HB Zinger. They played CBGBs on a Saturday night, so meaning they were not huge but well-known within the New York. If you listened to rock in the New York world, you probably were aware of them. And they were at an independent label and we designed a cover, which ultimately that cover was nominated for a Grammy, which really put us on the map.

Because I had had meetings with all of the major labels and some of the independents, and they liked the portfolio, they liked what I had done previously and said they’re going to give us jobs. But those jobs really never came until the Grammy nomination, I guess, where they saw that, “Okay, he can just do it for the portfolio, but he actually can see through a project all the way and into print.” Which I now would think is very much fair enough because there is a huge difference between doing something for your portfolio or actually getting something done that’s still of quality that actually lives out in the world because there is a lot of shepherding and protecting and being, I don’t know, persuasive in meetings to protect it and all sorts of things like that. It really, I do believe that getting things done is probably one of the four most qualities that a designer needs.

What do you mean? The ability to kind of, we would make shit happen essentially?

Yeah, yes.

To really conceive of something that no one’s ever conceived before, convince other people to do it and just do it.

And be able to realize that within a budget and a timeline, and being able to see what that situation desires and shepherd it through a process. Specifically, let’s say if we stick within the music industry, which is often very complex because you have a band, a management of the band and a record label that’s by design often have quite different goals. And to be able to protect the piece against those forces is I think its own little needs, its own little craft.

Do you, another guest of mine from the design field, Paula Scher also got a lot of her start from doing album covers. Did you enjoy it at the end? I mean, you did many of them and they were extremely successful and won awards and all sorts of things. Was it something where you… I think it’s probably hard to make a studio just out of that, I’m sure, because it’s probably just budget wise. But is that something, did you look back on those days fondly of doing those projects and-

Yes. Oh, totally. I mean, as I said, it had an incredible amount of difficulties in shepherding them through the different forces. But in general, I believe that visualizing music to be one of the single most interesting tasks you can ask for as a designer, because you’re ultimately working with something extremely emotional that itself is not visual. So, I always thought that creating album covers is so much more of an interesting job than let’s say film posters. So, both of them are popular out forms, but the film poster you ultimately have to distill something that’s extremely visual into a single image, which is just inherently much less interesting than to come up with an image of something that is inherently non-visual, but very emotional. And so, I also believe, I’m convinced that if you look at the history of album covers, the quality is infinitely higher than if you look at, that’s the history of film posters. Because ultimately they’re distillations relations of a long story into an image.

Often you have to feature the main actress or actor, which sometimes is the case in albums too. But even that to create, to come up with a portrait of something that is non-visual and emotional is much more interesting than distilling the film.

(SPONSOR BREAK)

And to fast forward a little bit, because it relates to some of your new work. It is what I mentioned to you right before we joined the call was the 2016 film called “The Happy Film,” where it’s a documentary where you sort of search for happiness and fulfillment, both personally, professionally, love life, everything. And I’ve always wanted to see a follow-up and see kind of what happened. I mean, that film was very… I mean, you very much bared your soul in all sorts of angles in a way that it’s quite brave. And of course, I would compare it to other works where you’d be naked and you’ve drawn yourself or whatever. What was the aftermath of that film for you?

I think the biggest joy in the aftermath was that the film was done and that didn’t have to continue working on it. I think that out of all of the projects that I’ve ever attempted in my life, I think the film was the one where I had the longest periods of true unhappiness, anxiety, and dread.

Oh gosh.

And that’s-

Did the film make you feel that way or was it just happened to be the film was a reaction to the unhappiness?

No, I think it was the process of making the film that made me that way. The things that we tried out in the film, and as you know, it’s like I try out cognitive therapy, meditation and drugs as efficient methods to make me happier. I think ultimately all of those three methods worked, but I had completely underestimated the difficulty of making a film. I had underestimated how much we all including myself, are spoiled by so many quality films that we’ve all seen and how difficult it really is just to make a film that’s watchable that you don’t turn off after 10 minutes. So yeah, I think that I had gone into this project thinking I had done numerous books about big subjects. Let’s do a film simply for it to be a challenge. I could have also elected do a book about my happiness would’ve been much, much, much easier. But it really was the making of the film that was difficult.

And however, I would say that this was sort of a little hope in the beginning when we started the project that the research into this world of positive psychology, might give me insights that ultimately might make me happier with a little side thing in the back of my mind. And interestingly, not immediately, but a couple of years after the film was done, this actually became true. And it became true from something that I already had known before we started the film, but I had only known it in my head. And through considering and involving myself in this subject for eight long years, I actually was able to internalize this knowledge. And the knowledge is something that Jonathan Heights, the scientist in the film who I have who sometimes checks in on me, he’s in the film, had written in his book as the conclusion, which is that you should not run after happiness or try to be happier. But what you can do is to look at your relationships, the close ones and the far-off ones.

So, anybody from a partner to family to acquaintances, and see if you can lift the quality of those relationships onto a level where then when you don’t expect it, little happiness can come out from in between. And you can try to do the same with your work and the same with something that’s bigger than yourself. Even though I had read that way before I even started the project, it had zero influence in my life. It only had an influence once I deeply immersed myself into the project, which ultimately I think is the reason that almost none of self-help books or self-help films have any impact on anybody, because the connection between a reader and the book is too surface-y for it to really work. Many of the books, most books that I read, and I think I read about a hundred, in that world had good content.

It was not the problem of the content, it was the problem of the involvement, which is why a therapist will very much likely be more effective than reading a book. Not because it might be that the book has the exact same content as the therapist. It’s like going to the gym by yourself or doing a one-to-one class with a trainer.

And so if I asked you today, are you happy?

I’m doing pretty well. And obviously I’m not happy all the time, but I did do that. I did look at my work and did check the last couple of years, meaning as simple as going through my, at that point, digital diary, look at all my meetings, look at all the jobs we had done in the last five years and just elected which of these things were very positive experiences, which of these were not. And then made a decision, “Okay, let’s get rid of all the ones that didn’t and let’s do more of the ones that did,” which for example was a very firm decision on not to make follow-up on “The Happy Film” because it wasn’t an enjoyable experience. And I would have to admit that the second film would actually likely be more enjoyable because I now would know much more of what I’ve been doing and where we went wrong so incredibly in the process of the first film, but it still would be a huge struggle.

And you shared a studio with Jessica Walsh, a business partner I believe that ended in 2019. And even talking about Matthias who used to be in your studio with you and pictures together. And there’s kind of, for a very well-known designer you kind of treat these business partners as equals in a visual sense and even in the naming of a firm, and Jessica was quite young when she started working with you. What do you think… Is this something you think in particular to you or do you think other designers and artists could kind of learn from this? Because sometimes as a journalist, sometimes I interact with lots of different architects and designers and artists where there’s a lot of protecting of the image of the single artist as the soul kind of creator, and there’s a lot of ego in that. And do you think others could kind of learn from this sort of way of thinking?

I mean, I don’t think that my own ego is particularly small.

Really?

But I am aware that I’ve always never, I mean even including the old Alphorn days, done something all by myself. Design in that way really truly is a team effort. And I think ultimately not all of us, I don’t think that I’m flawless in that at all. But ultimately here and there, I try to treat other people how I would like to get treated myself. And if somebody makes a serious contribution, and that would’ve been the case with Jessica or with Matthias, they should get the credit for it. And as I said, I don’t think that I’ve always been, I definitely would not single me out as a model of that, not at all. But I’ve tried.

I guess from the outside it seems that way that there’s kudos to you for doing that. And 2018 before the last studio with Jessica had ended, you did a show called Beauty at Vienna’s Mac Museum, the design museum there. Where it’s about sort of, pushing back in this notion of beauty for the sake of beauty, not having any value. And so what made you feel passionate about that?

Well, mostly because we had the experience in the studio that whenever we took form seriously, whenever we worked hard on the form, it seemed to work much better. So we realized that this notion that’s very widespread in design, but also in architecture, that it’s all about functionality really leads to pieces to work that doesn’t function as well as it could. Famous examples would be the 1970s public housing projects that ultimately in many cases didn’t function because of their lack of beauty. Because their coldness seemed to inspire all sorts of bad behavior, including high crime levels to the point where people didn’t really want to live in them and they turned out not to be functional for human habitation, which is quite ironic considering that the style that they were built under was called functionalism. And I’m absolutely a hundred percent positive sure there is even very good evidence for that. That if beauty would played a larger role in the design and execution of these buildings, those crime levels would have stayed lower. People would’ve loved them more and they would still be standing today.

Because one of their non-functional thing is of course that they were so short-lived, many of them had to be dynamited 20 years after they were built. And this very, very same is true for all areas of communication design. Websites that have been considered to be beautiful, not just formally, but also in their functioning like, how beautiful is that transition from this part of the side to that part of the side? If you press this button, how beautiful does the next thing appear? All of these things will actually make you stay much longer on that site, increase the functionality. But because so much of interface design is inspired by engineering and so many of interface designers come from a more technical background, the god in that world is still very much functionality. And I’m a hundred percent sure that’s the teams who figure this out to really bring beauty into that space will be crazy successful. As we already see that, I think that the leading company in that space who really considers form is Apple and they seem to be doing quite well.

And speaking of fulfillment, you’re known for these seven-year cycles or… Are you still sticking to that cycle, and how many cycles have you had and where did this idea come from?

So I’ve done three sabbaticals, full year sabbaticals. It’s almost seven years of work, one year sabbatical. I think the idea originated with my late brother-in-Law who I was very close with. He actually, and I actually traveled to the United States and to New York for the first time right after I graduated from high school. And he was a high school professor and he had done a sabbatical. So it was in my mind from there, but I was of course not aware that you could do this also outside of academia or a school system. And when I opened the studio, it was just after seven years that I felt we were doing repetitive work. I felt that I needed some sort of free start, even though meaning on paper we were very successful. Meaning that the studio was established, we had done covers for the Rolling Stones and Talking Heads and Aerosmith and Lou Reed so we were… From that point of view, it worked really well.

I had done a talk at Cranbrook and they had very sophisticated grad students that did some serious experimentation, where I felt a bit jealous about. Tibor Kalman my big design idol had died and I felt, I don’t know, that drove home the shortness of life and the importance of using it to its best advantage and all of these things conspired to make this happen. And of course, I was scared shitless in front of the first one. I thought they’re going to be forgotten. I thought it’s going to be looking unprofessional. And all of those assumptions after the first year turned out to not be true at all. All the clients, not most of the clients came back. We were not forgotten. We had gotten an incredible amount of press for not working because this first one was in the year 2000, in the middle of the first internet boom where it was very unusual to close a studio for a year.

And ultimately that first sabbatical proved so successful. And by successful I mean that so much good work came out of it that we then executed in the years afterwards when the studio was open again that there was no question, I’m going to do a second. And the same thing happened in the second one. Meaning the second sabbatical yielded a completely new direction in furniture, but it also yielded ultimately “The Happy Film,” meaning the start and the idea all happened in that second sabbatical. And now looking back on it, I would say that the majority of my favorite projects that the studio had done, meaning the ones that I really feel, “Oh, this was worthwhile.” Which “The Happy Film” would be part of. It was difficult to do but I think looking back on it, I think it was a worthwhile project. The majority of those worthwhile projects had their origin in a sabbatical.

So I keep on doing them even though right now the work in the past four years, I haven’t touched any commercial work and concentrated on really almost exclusively or no, exclusively on work that’s connected to long-term thinking, which really is my new subject that I’m still going to go on sabbatical the next one is going to come up in fault ‘24, even though the difference between what I’m doing right now and a sabbatical isn’t probably as big as it used to be.

And you kind of take on these projects for these sabbaticals, right? These sort of creative… Things that are outside of your practice like furniture for the last one. Have you thought about what the next sabbatical will even look like?

I’ve thought about locations. And what is basically the desire is always to do something newish. So it looks like that my partner Karolina is going to come along on the sabbatical. That’s new. I’ve never done that before. And so to do it as a couple. And we are not sure yet but we are thinking maybe three locations in Latin America, that would be a possibility. But then there’s also something completely different where we would take three locations around the world that are completely different from each other. We both like Bangkok, we both like Tel Aviv. So who knows? As far as the projects itself is concerned, I’m not sure yet. It could even be that it’s new in a way that I continue the current project. I’ve never done that either before because so far it was also always very, very, “Oh, it has to be the exact opposite.” So who knows? I think my only real desire is that the sabbaticals don’t repeat themselves.

So let’s say it would be fantastic to go to Mexico City because I already know it, but I’ve already spent part of the last sabbatical in Mexico City so that’s basically out, that’s for sure we’re not going to do that. It would be also, it’s a bit too easy I think that part of the sabbatical is also that it should be somewhat challenging.

(SPONSOR BREAK)

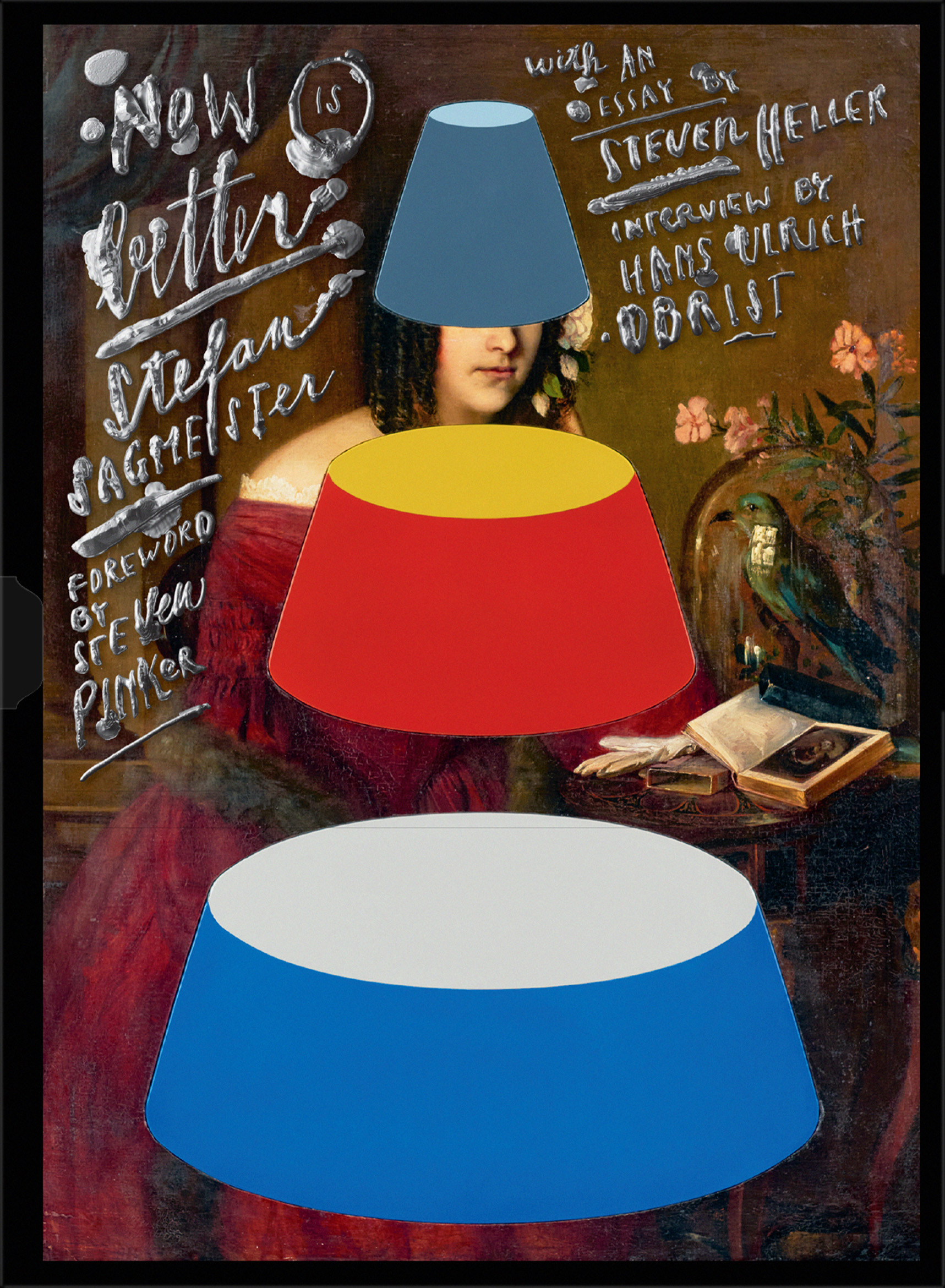

Sagmeister’s wildly inventive style seems perfectly tailored for books. And his latest Now is Better is no exception. His favorite partner would be Phaidon, the arts design and style publisher that just celebrated 100 years in the business. So Stefan and I decided to invite Deborah Aaronson, the group publisher to join our conversation and discussed this rare milestone in the culture of design and the enduring power of print.

Deborah, thank you for joining us on this little chat and congrats to you and the Phaidon team on the hundredth anniversary of the publishing company. Can you tell me a little bit about the history of Phaidon and sort of a brief 100 years in 100 seconds overview of this incredible company?

Deborah Aaronson: Absolutely. Well, the company was founded actually in Vienna, in 1923. And like a lot of publishing houses during that same time period, they moved their offices from Vienna to London with the sort of rise of the fascist government. And so Phaidon is really technically a UK based publishing house. We’ve had our sort of main office there since we moved there. And then over the course of our history opened the office in New York and have developed a full editorial design sales and PR team out of New York. And the company is privately owned and has been so since the beginning.

And if I were to say there are lots of art and design publishers out there, I would say there’s maybe five of them that are on top, right? And you guys are one of them. And what would you say is today in 2023 kind of part of the key personality trait of Phaidon that makes it kind of what it is and successful?

Deborah Aaronson: Well, I think we’re very internationally focused and I think that’s a big part of it because the company was based in London, we’ve always needed to have full global distribution of our titles in order to have a financially viable organization. Unlike some other companies which were American based from the beginning and they really saw North America as a big enough territory to establish their business and have their business. And I think that that really informs a lot of the different parts of our program. It informs what kinds of books we publish, it informs our design aesthetic and how we think about what our books should look like, who we think our market is. So I think the international aspect of it defines a lot of the reasons why Phaidon is the way that it is.

And Deborah you know Phaidon is now celebrating this with a new book. Tell me about this new book, this sort of 100 Years of Creativity and how the idea got started and what is it?

Deborah Aaronson: So we all of a sudden realized at some point that we were coming up on our hundredth year anniversary and we were like, “Oh my God, we should make a book.” And we wanted to do something that was somehow representative of the spirit of Phaidon without being a kind of technical history or something like that. We actually, there is a book which talks extensively called Emigres, which talks extensively about Phaidon’s history. We didn’t want to do that. And we wanted something that would not only highlight the hundred years, but really highlight the most important people in our bookmaking process, which is the creatives and authors and chefs and architects and designers and artists who create the content that makes our books possible. And I was actually walking back from a dinner with a colleague when I was in London for our sales conference and we just sort of said, “All right, well maybe what if we just did a book that was a 100 Years of Creativity.”

You have one entry for each of the years. You randomly assign one of our authors a number and ask them to create something that would live on that page along with their name, how they characterize their occupation, where they are. Because like I said before, the international component is so important for us. So to emphasize not only who the contributors are but where they’re working from was really important to us, and we were very open about it. We sort of said, you can do something related to the number you’re assigned or not. You can do something related to the anniversary or not. The only thing really that we asked was that most people try to do something in a vertical format because the book is vertical. And then it was just a matter of reaching out to… We came up with a list, reaching out to people and then just waiting to see what they created. And we were surprised and not surprised. We know we work with tremendously talented, inventive people, so we got back things that we would’ve never expected to get and they were really wonderful and really different from one another.

And drop some names of all… Obviously Stefan is in it. I’m going to get to asking him what he’s doing. But who are some of the names out of a hundred do you think that you can rattle off?

Deborah Aaronson: Dieter Rams, Annie Leibovitz, Rihanna, Stephen Shore, Grace Coddington. Yeah, it’s a real range of across all… And Enrique Olvera. Yeah, a real range across a wide range of disciplines.

Stefan Sagmeister: Then me.

And you.

Stefan Sagmeister: Me, Rihanna, and Annie. That’s just that.

Deborah Aaronson: That says it all. What else do you need?

So Stefan, how are you going to outdo Rihanna? That’s a really good question.

Stefan Sagmeister: Thankfully, Deborah did not share the other people’s entries into this otherwise I think I would still sit here stuck with, in the biggest author block. So no, I have no idea about the other 99 people. That almost sounds like a Jay-Z quote, no. But the other 99 people did for this project and I did… Well, I don’t know should we discuss what I did or should this be a surprise? I have no idea.

Yeah, this is one out of a hundred is okay to give away.

Stefan Sagmeister: Okay. So basically I did a tiny little research, which I think in my case meant I looked up findings in Wikipedia page, which means-

Deborah Aaronson: The go-to source.

Stefan Sagmeister: Exactly.

Deborah Aaronson: Excellent.

Stefan Sagmeister: And discovered there, which I did not know that it was indeed founded in Vienna. And because obviously I have to do working right now with a lot of data and a lot of things that became better, I ultimately looked at the markets that Phaidon was in the past a hundred years and looked at how book publishing increased in those markets or decreased. I kind of assumed that it would be increasing, but how many titles will be published in those markets in those years? So a hundred years ago, 75 years ago, 50, 25 and now. And then we looked at those numbers and cut Vienna sausages into exactly those kind of links and photograph them together with [inaudible 01:10:50], who is a fantastic photographer and that I’ve been working with for quite a while.

Stefan, is there a book in the catalog that you think really stands out for the design?

Stefan Sagmeister: I have one right in front of me, which is the Ellsworth Kelly book, which is from a design perspective, I think quite a conservative, a very matter of fact kind of book, which is appropriate to the artist. And I think like many of the Phaidon books, it’s not everything needs to be flashy, not everything has to come in a blown up pillow. But that book needed to, and the Kelly comes in very a red slip case that’s as conservative as it could possibly be. I think it’s covered in fabric, and it’s just right. And in many ways the opposite of the one that you just described, but also good.

Just right, I think is a nice way to conclude this part of the interview. But Deborah, is there anything else that we haven’t touched upon from a Phaidon perspective? Just in case I forget. And yeah, I think—

Deborah Aaronson: I don’t think so. I think—

And the book is coming out so sell us a couple of copies of the book. The 100 Years of Creativity comes out when?

Deborah Aaronson: I believe it will come out in September. And actually the book is not for sale. It is being created exclusively for people who work at Phaidon, for our contributors, sort of VIPs involved in the organization. We’ve really just sort of—

Podcasters…

Deborah Aaronson: Podcasters, we can probably fit one or two in named Dan.

Okay. Good, good.

Deborah Aaronson: But yeah, we really made it for ourselves in a way.

That as anyone who knows anything about publishing that couldn’t be more wonderfully self-indulgent it sounds like.

Deborah Aaronson: Exactly.

Dan Rubinstein:

So kudos to you for doing that in a volume business.

(MUSICAL BREAK)

Stefan’s latest phase, which includes the Phaidon book “Now is Better,” is radical in many ways. But key to all of it is how downright optimistic it is. I wanted to ask the designer why he chose this topic, and how his work cycles fit into his modern life.

And moving into this new sort of now is better phase of your career that has this new book. You had a show called “Beautiful Numbers” at the Franz Meyer Museum in Mexico. And it’s all about sort of taking the long view on everything but also especially on humanity and progress. What sparked this particular idea and this now is better phase?

Well, I was lucky to be invited as an artist in residence at the American Academy in Rome. And one of the best features there is its food program, which is absolutely fantastic and delicious was put together by Alice Waters and has the fantastic side effect that the food at the American Academy is basically better than it is anywhere else in Rome. Which means that all of the people who are there, all of the artists, all of the designers, the writers, the filmmakers, the archeologists have lunch and dinner there, plus anybody that you find interesting in Rome, you can invite to have lunch and dinner there. And they are more than happy to come because it’s quite well known in Rome how good the food is. And the environment is scorches, if the weather permits it’s in the courtyard. And so twice a day you have a quasi-salon there. With very interesting people you always sit next to somebody else.

And one evening I was seated next to a quite well-to-do lawyer who was the husband of one of the invited artists. And he told me that what we are seeing right now in Poland, in Hungary and in Brazil really means the end of modern democracy. And after dinner I looked it up, when did modern democracy start? What’s the story with it? How did we develop historically? And it turned out that 200 years ago there was a single democratic country, the United States. A hundred years ago, there were 16 or 17 after World War I, and now we have 86 or 88 depending on how you count democratic countries. So he couldn’t have been more wrong. We’re actually living, and this is not an opinion, this is factual. We are, like our decade when it just went back a little bit, but it always progress, always goes forwards and backwards a little bit. But you can state that we are living ultimately in the golden age of democracy.

Never in the history of humanity did more than 50% of all people on earth live in a democratic system. And that insight or the insights that this highly educated, smart person could have been so wrong about a pretty significant fact of his life was super interesting to me. And I looked into other things. And I had the time at the academy and I found that basically everything with very few exceptions, if you look at it from the short term looks awful because things that go badly tend to go badly very quickly, like scandals and catastrophes. And things that go well tend to improve very slowly and don’t lend themselves for a very fast media cycle. And so it just became apparent to me that there are really two opposing views to look at the world. Short term, everything looks shit. Long-term, everything looks fantastic. And considering the short term is very much taken care of by almost all media. From Twitter to newspapers to cable TV news, they take care of that. I felt it would be interesting to look at the long-term and try to communicate that.

And of course the first question, if you look at something long-term is, or if you look at the medium, how do I communicate the long-term is, “Oh, what would be a good long-term medium?” So immediately out the window went everything digital because it’s terrible long-term. If clients ask me for files that we did 20 years ago, it’s basically impossible to open them because they’ve been stored on mediums where that hard drive is long obsolete. It is somehow possible, but it’s extremely difficult. So I looked for media that are more long-term. And what came to my mind pretty quickly was old paintings. And we actually had some in the attic of the house that I grew up in, stuff that my great great granddad wasn’t able to sell in his crappy antique store. And those were the first ones that we transformed basically cut up and inserted contemporary pieces into those old paintings that looked like abstract compositions, those contemporary pieces but are ultimately data visualizations.

So they’re very much designed even though they hang on the wall and might be mistaken for art but I see them very much as pieces of design, as data visualizations and people like them. So we started to make exhibitions with them. You mentioned the one in Mexico that’s now traveling to many other museums in Mexico. We just closed an exhibition in New York that we are now sending. And actually just before we talked I was designing the poster for the exhibition in Tokyo that’s then going to go to Seoul and from there possibly to China. So it seems to work and I feel that message is to me, to my heart just as important as the beauty message. It’s something that many people surrounding me, my friends, my acquaintances, are quite unaware of. I think most people or many people are aware of. Well, when it comes to longevity, we are doing better now than we did 200 years ago. In fact, we are doing two and a half times better now. We live two and a half times as long considering most people are rather alive than death. That’s progress.

But that is true for many other aspects that are close to our hearts. That’s true for war. We live despite what’s going on in the Ukraine right now and in Russia, despite that we live in some of the most peaceful times in history. And this is again, these things are not opinions of mine. There is very good data about these things from signed off by the United Nations, signed off by the World Bank so this is… Well, we can go in many different directions. This would be true for food. Extreme poverty is now the lowest it’s been in human history. This is true for health. We are the healthiest generation of many, many… It goes in many, many other directions. And I would say the only area that we have a problem that we really didn’t have before would be the environment. Even though the CO2 accumulation in the atmosphere started 200 years ago with the Industrial Revolution, it wasn’t the problem until now. And so of course there are problems now that we did not have before.

I’m also very, very, and I think that that’s part of the reason why I find this subject so worthwhile. I’m convinced that we have a better chance of solving these incredibly difficult problems from a platform of knowledge that we have achieved already quite a lot, about serious problems of the world in the past then from this platform of doom and gloom, meaning I have acquaintances who literally wouldn’t have children for the declared reason because they think that the world is so terrible, you cannot… It’s immoral to put kids into this place. And the meaning I myself, knowing our history and having looked at the world from a long term perspective now for the past years really, am convinced that this is the wrong way to think about the world. That it actually, that’s the likelihood that kids who are born now will live in an incredible, interesting and fantastic environment, is very large.

I’m actually jealous that I just did a longevity test, for all rational reasons I’m going to live until 89. Meaning I have another 28 years on this earth, which I’m looking very much forward to. But I think that in 50 years from now, it’s going to be even much more interesting.

And with all of your studies for “Now is Better.” Is there anything you’ve discovered where now isn’t better-

Oh yeah, for sure.

… For the environment, I guess that’s going to-

Absolutely. I mean, for sure the environment and that would be including things like the dying off of species. At the same time, and I think I pointed out in the book. It’s not that the entire environment is fucked. If we look at just when I arrived in New York City, the Hudson was completely, totally polluted. And the idea that you would actually eat a fish that comes out of that chloride like thing was ludicrous. And I think we are not quite there yet. I think there’s still a little bit of warning. I think that the New York health authorities say you can eat the fish from the Hudson, but don’t do it if you’re pregnant and don’t do it if you’re under six years old or so. So there is some caveat that’s there, but it’s very much I’m convinced that in a couple of years we’ll all eat Hudson fish again.

And the same would be true for my hometown. I mean, this is just my own experience. The Lake of Constance that Bregenz is adjoining is much cleaner now than it used to be 20 years ago when I… Or 30 or 40 years ago when I grew up there. So definitely there are things that are moving, very much moving in the right direction, but at the same time there is gigantic problems that we have to face and solve.

And my last question on this theme is I’m wondering if there’s any aspect of your life that is better now than it was before the pandemic? On a personal note, is it maybe a hobby or a routine you started or something that is better now than it’s ever been for you?

I think I’m a very lucky person in general. And so the pandemic actually brought me and my partner together. Because pre pandemic we were kind of in a loose, long distance relationship. And she moved to New York just before the pandemic and the pandemic really made a proper tight real relationship out of there. So in that way I’m quite thankful for that situation. And similarly, it of course, the pandemic allowed me to really concentrate on the subject. Before, meaning I traveled heavily, I did sometimes up to 50 talks in a year, many of them international. Which of course was also quite time consuming, and being stuck in the studio here definitely moved that subject forward much more efficiently than if I would’ve stayed with my regular life. So I can say that this was mostly a positive experience for me. And I can see definitely from a scientific level, I’m meaning so many of my acquaintances who are in that world think that this really unprecedented international cooperation on a single subject that was important for the entire world moved many areas of the sciences forward incredible.

And I think looking back on it, we will look at this post pandemic time as being incredibly fruitful and huge steps having been made.

(MUSICAL BREAK)

Thank you to Stefan Sagmeister, Deborah Aaronson, and to everyone at Phaidon for making this episode happen. The editor of The Grand Tourist is Stan Hall. To keep this going, don’t forget to visit our new website and sign up for our newsletter, The Grand Tourist Curator, at thegrandtourist.net. And follow me on Instagram @danrubinstein. And don’t forget to follow The Grand Tourist on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you like to listen, and leave us a rating or comment. Every little bit helps. Til next time!

(END OF TRANSCRIPT)

Plus, an exciting young British artist receives a retrospective, Marcel Dzama's whimsical drawings take a political turn in L.A., and more gallery openings.

Through her books and products, this 21st-century domestic goddess is truly a part of the classic American style firmament. On this episode, Aerin Lauder speaks about growing up with her grandmother Estée, what she's learned over years of being in the business, and more.

The best of museum openings this week, from Barbara Kruger’s words landing in Bilbao to Jenny Saville’s fleshy nudes coming to London.