What to See, Experience, and Explore at Miami Art Week 2025

We checked in with our former podcast guests who will be inching through Miami traffic, unveiling new works, signing books and revealing new projects this year.

This article is from our first-ever print issue, available for order online now.

As Korean culture rapidly dominates the global stage—from K-pop to Hulu’s Squid Game—the designer Teo Yang has made it his mission to bring Korea’s past into the future, using new technology such as 3D scanning and AI to achieve his goals. These high-tech helpers, however, were markedly absent at his studio, which is composed of two adjacent hanoks, traditional Korean houses built over a century ago in the Bukchon neighborhood of Seoul. Surrounded by beautiful objects of traditional craft, midcentury pieces by Pierre Jeanneret and John Dickinson, and one-of-a-kind furniture by Yang himself, he served me tea as we discussed his studio projects, which range from residences, galleries, and Michelin-starred restaurants to handmade furniture and a line of skincare, all to achieve his mission to incorporate Korean craft and aesthetic into contemporary design. Of course, speaking to the most connected design tastemaker in Seoul, I had to get his personal recommendations on what to see in his favorite neighborhood of Jongno, from art spaces and restaurants to must-visit tea shops.

I’m embarrassed to say this is my first time in Seoul, but I’ve wanted to visit for many years. When the opportunity arose to meet you and to get your personal recommendations for Seoul, I couldn’t pass it up. But first, can you tell us a bit about yourself and your background?

I’m an interior designer, but I could also say I’m an entrepreneur. I was born and raised in Seoul, but I went to school in Chicago, at the Art Institute, then I did my master’s at the ArtCenter in Pasadena, California. But I didn’t graduate—I got an internship in Marcel Wanders’s studio in Amsterdam.

How long were you in Marcel’s studio?

I was there for only for a year, and then I had to come back to Korea for military service, which felt like a huge distance from the design world, but it was fun actually. Coming back home, I realized that there’s been a lot of issues connected with the development of the city. I’m not sure if you have felt it as a visitor, but the speed of the city itself is actually very, very fast. People are very sensitive to trends, and people are very sensitive to change. There’s this entire urge and obligation that the country puts on—that you need to develop not only yourself but your surroundings as well.

I think it comes from the historical background that we have, especially the Japanese occupation era. We lost so many things that we feel this urge to catch up. And then the Korean War happened right after, and that also did a lot of damage to the whole country. So we needed to do a lot of catching up, and we needed to repair a lot of the country. Then the economic growth came, so we really didn’t have a chance or luxury to look at the traditions, heritage, and local values that we have lost. And so, there’s been a lot of architectural changes, building, and development projects.

But building doesn’t always mean something being constructed, it also means you need to deconstruct something in order to build something new. So when I moved to this neighborhood 12 years ago, I was confronted with those issues pretty much every day. I would see a beautiful house being torn down and turned into a fancy building. And I would see beautiful trees that have lived more than 700 years being cut down, and the land turned into another commercial project.

When did you first become aware of the idea of preservation of culture through architecture and design?

It actually happened when I returned to Korea and moved to this neighborhood of Bukchon. This neighborhood is one of the oldest residential areas, so it has more than 600 years of history. But even in a historically preserved place like this, you see things disappearing and only façades remaining, and the narrative inside is disappearing, too. It’s really funny: There’s this neighborhood near here called Ikseon-dong, which used to be an old residential area with only traditional Korean houses, and people used to live there with their house doors open. You could smell their dinner cooking, and you could literally hear them talking, having a family conversation inside. But that small community has totally changed into something very commercial.

I’ve been walking around this neighborhood where you are, Bukchon Hanok Village, and it is a very charming place: the scale of it and the mix of mostly traditional with some newer things, low one- to two-story residences mixedin with smaller commercial buildings. No high-rises, no full blocks that are completely new. How many neighborhoods like this are left in Seoul?

Not many. Mostly in Jongno. Insa-dong, where you are staying, or Ikseon-dong, which I was just talking about, have totally turned into commercial neighborhoods—the best-selling product there is soufflé [laughs]. So it’s kind of bizarre. The content is gone, and only the façade is there.

I think the basic unit of inspiration is a traditional house, which is the hanok, and your office is composed of two adjacent traditional hanok houses put together. What are some of the lessons that you’ve learned from this type of architecture that you’ve applied to your contemporary projects?

I think the most beautiful thing about the hanok is how you use nature and how this architecture really lets in light and creates shadows. And it changes throughout the day and throughout the seasons. It’s something that we cannot control and something that we cannot create. I think this house is an entire celebration of that. So I try to mimic the same conditions, and bring in a lot of those features into our new spaces.

Do you end up using new materials in order to achieve these goals?

I’m not trying to mimic the past. I’m inspired by it, but I’m really trying to create new visuals out of it. So obviously even in this house, you see marble, you see stainless steel mirrors, and glass, and so on. I think the mixture of it all shows that you can embrace these contemporary materials and forms. We just need to shy away from the idea that existing with nature and borrowing from the landscape is something only found in the past. We shouldn’t forget that we’re just a mere part of a small being, and we are also part of nature, and a part of our past.

I really felt that, as a designer, I needed to show people that tradition and heritage is a great resource that we should not neglect, and create an archive, find the possibilities, and share with the world that there are great things we can rely on and create something new from it. So that has been my mission for almost 12 years now. My studio’s mission is translating and connecting tradition and heritage to the contemporary world. Based on that, we not only do interior design, but we run a furniture brand called Eastern Edition, a cosmetic brand called Eath Library, and a perfume brand called Sinang.

That’s an impressive number of enterprises.

Yeah, it’s a lot. I think it didn’t really come from the need of wanting to do that many things—but it came out of a pure affection towards what Korea has, and what we can offer. So there’s this great tradition of not only architecture and interiors, but also furniture and craft with beautiful local materials. And with our four different, very distinctive seasons, we had to come up with unique techniques in order for all the materials to come together, since the wood expands in the summer and shrinks during the winter. So all of those, and also the beautiful narratives on nature and how we always think about how to live with nature. Those are the key things I talk about when it comes to my furniture brand.

And for the skincare brand, we work with Four Seasons Hotel, the Plaza Hotel, and Signiel hotel—pretty much all the five-star hotels in Korea. And they’ve chosen us because we showcase Korean hospitality through our skincare brand. How do you treat people, but also treat yourself? What are the traditional herbs to use? And what are the royal skincare methods that were once used? So we put an extensive amount of time into research trying to translate all of that into a visual outcome. For the perfume brand, we use AI to create scent notes. I write stories and those stories get transformed into scent data. And based on that, we create samples and we choose what we think best suits the story. Overall, it’s about connecting what we have around us, and what we can take from the past into our modern life, and into the future. There’s always this fear that the old things might disappear. Even for these earthenware pieces that I’ve collected for many years, some come from the fourth century to eighth century—I’ve 3D-scanned all of them so I have them in data form, and I’ve used AI engines like Midjourney to redesign them and give them a new life. I’ve reprinted them to use them as diffusers and vases.

For you it’s not a stretch to incorporate new technologies like 3D scanning and printing, and now artificial intelligence as well?

Yes, definitely. It’s like the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris—they were able to scan the entire cathedral so when it caught on fire, they could re-create the elements lost in the exact same way. There’s this technology that we can really utilize to have a better understanding of what we have. It’s been a mission for me for almost 13 years to do so, and it’s all we talk about here in the studio, and everybody is so focused on the topic. And we’re really a team, I’m not just someone who hires and pays them monthly. We really take our mission very seriously.

Are clients receptive to your ideas?

It’s not easy for a designer to work under one mission. A client came to us to design a French restaurant, Honnêtes Gens, in the area of Gangnam. He was very interested in 1920s Paris, and he was very interested in the crafts of Japan and how Charlotte Perriand and all of those modern designers were inspired by Asian culture, heritage, and craft. We asked him, “If you’re opening a French restaurant in Seoul, what is the message you want to send?” We really wanted to tap into what was happening in Korea during that time—what were the craft movements—and how we can match that with the Parisian aesthetic to create something new.

And you feel you were successful in synthesizing a Korean aesthetic with French Art Deco?

Yes, definitely, because a lot of woven things like this [pointing to the caning of a Pierre Jeanneret chair], it’s such a common thing in Asia. It’s like the most basic form of making baskets or even creating something for the rooftops of old houses as well. We were able to bring in a lot of traditional artisans to work on it and even use lacquer paints within the space.

I’d love to ask what you would recommend to a visitor who’s sensitive to design and culture, but has never been to Seoul, like myself.

I would say even Jongno itself—where we are—is such a big neighborhood. Within Jongno, there are so many museums, and so many galleries, and so many places to mention. Jongno is one of the oldest neighborhoods in Korea.

What museums would you recommend in Jongno?

Well, there’s Seoul Museum of Craft Art, and there’s Seoul Museum of Art, and I would definitely recommend both of them. The architecture itself is so beautiful, and with the contents, you could really understand Korean art and Korean contemporary art, and also Korean contemporary craft and traditional craft. And everything is so close together. Everything is within walking distance in Jongno, which is a nice place to walk. And so I would recommend those two museums.

I went to the craft museum yesterday—my favorite thing to see is the craft of a beautiful country. I was very taken by the traditional raincoat, which is made out of straw so that the water goes right off. Is there a particular object in the museum that you enjoy looking at?

Well, there’s so many, but I love the part where it describes the room of a scholar. I think it really shows the attitude that they had towards themselves and how they were looking at the world. Even though they had so much wealth and so much power, the things that they possessed are very simple. So I think it really shows that these people had this way of living, that they went past the decorativeness, past the poshness, and then really had the taste to look at what’s the essence in life. I love that part so much.

Me, too. And if I were to look for some objects that would reflect this particular aesthetic now, is there a shop in Jongno or somewhere else that may have some simple, well-crafted things that communicate more than, like you said, poshness or trends?

Yeah, definitely. I love that topic of simplicity. Korea has really embraced simplicity. And we have a term for that. It’s called mumi. It means “no taste.” I wanted to recommend a restaurant called Uraeok. They make cold buckwheat noodles. It’s very plain. And they really want you to taste the pureness of the ingredient itself. So they are not adding a lot of other things, but really trying to focus on the mix of the broth, the deepness of the broth, and then the cleanness of the buckwheat noodle, and how that, too, could be combined to create a pure taste. And it’s not only about the taste of food, but we have an artifact called moon jar. It’s a white porcelain, and it comes in the late Joseon dynasty. We had a glorious history of beautiful, very decorative, and colorful ceramics before. But these ceramists abandoned all of that, and they went to a very simple form. And so, there is this taste and aesthetic that sort of flows in the whole history of really trying to eliminate the unnecessary things, to focus on what’s real. So you can definitely find the shops that sell those kinds of aesthetic beautiful objects. You can also go to the Seoul Museum of Craft Art, and you could see the simpleness of it, and then you can go to the store and then even purchase it for yourself. And there are some antiques stores around the neighborhood as well. So it’ll be fun to take a stroll.

I’m staying in Insa-dong, and I spent a few hours yesterday on the small street with all the shops. Why are there so many shops with beautiful brushes and paper in this neighborhood?

Well, that’s because a lot of the calligraphers come here to purchase paper called hanji. Han means Korea, and ji means paper, and they sell all these different brushes for different techniques and different drawings. And I think it’s very fortunate that we still have stores for those beautiful papers and brushes. And there are still a lot of people training themselves using calligraphy, just like in China, Hong Kong, and Taipei as well. And even for me, when I was in elementary school, my mom enrolled me in a calligraphy academy so I could learn and write my name in the proper way.

Is there another neighborhood you would recommend maybe as a contrast to Jongno?

I think maybe Itaewon could be a good place to go, since there’s the Leeum museum there. It’s a great museum, a great art center to see. And also there’s Pace Gallery. And there are so many great fashion stores and great places to eat. So I think Itaewon could be a fun place to see.

Is there something completely out of the way that you think is worth going to: a shrine or a park?

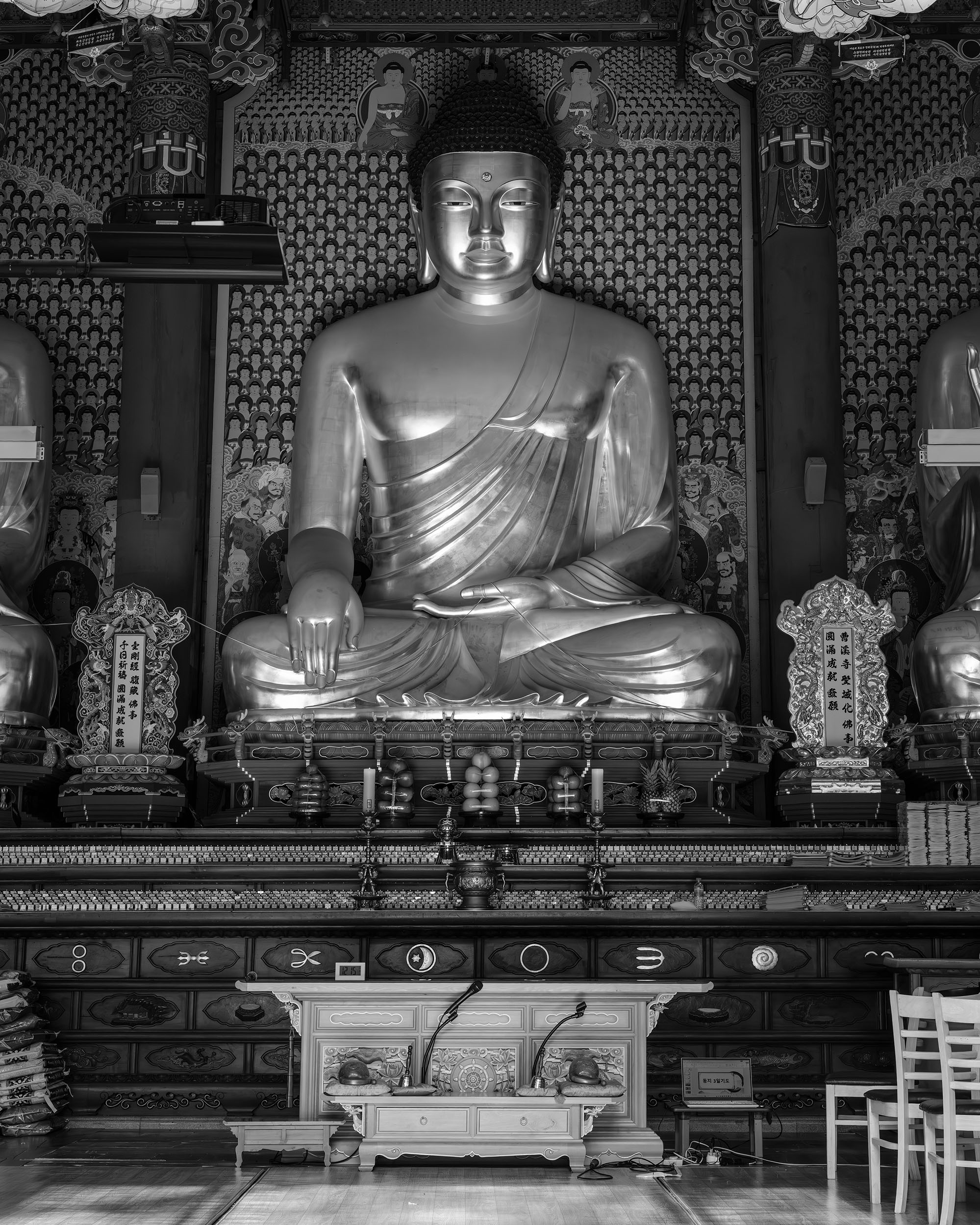

Yes, definitely. But I always like to recommend, if you are in the Gangnam area, Bongeunsa Temple. It’s a beautiful temple to go to after all your shopping spree in the Cheongdam area, or after a Michelin-starred restaurant, you can go to the Bongeunsa Temple to take a stroll and have a short meditation session. It’s a gem in the city. And if you’re in the Jongno area, you can always visit the Jogyesa Temple. It’s a beautiful temple with a long history. And you’ll see in both temples that many people come to pray and meditate. And just by sitting among them, you’ll feel right. I had some of my friends come from the States, and we would have meditation and prayer sessions together, and they felt very enlightened. And then if you really want to feel the serene atmosphere within the city, and not too far from Jongno, there’s another temple called Gilsangsa. I think it’s one of the most beautiful temples in Seoul, and I definitely recommend it.

And then lastly, what are two or three projects designed by you that a visitor can visit?

Oh, yes, I definitely recommend Kukje Gallery’s restaurant. It’s a restaurant that sits on the second floor of the most well-known gallery in Korea. It’s a powerhouse. And you should see Gyeongbokgung Palace, which you can see from the restaurant, with French cuisine. And I also recommend going to the Blue Bottle Studio, which is in a hanok. It’s not always open, but it’s a beautiful small studio where you can really enjoy coffee and really see the beautiful atmosphere. And also, I designed the Signiel hotel’s spa; the name is Retreat. If you go there, you can really experience our cosmetic brand.

We checked in with our former podcast guests who will be inching through Miami traffic, unveiling new works, signing books and revealing new projects this year.

The ecstatic designs of Chris Wolston come to Texas, Juergen Teller's most honest show yet opens in Athens, a forgotten Cuban Modernist is revived in New York, and more.

Tom Sachs explores various creative disciplines, from sculpture and filmmaking to design and painting. On this season finale, Dan speaks with Tom about his accidental journey to fine art, how an installation in a Barneys window kickstarted his career, and more.