Christine Ay Tjoe’s Abstractions Look Inward

Plus, an exciting young British artist receives a retrospective, Marcel Dzama's whimsical drawings take a political turn in L.A., and more gallery openings.

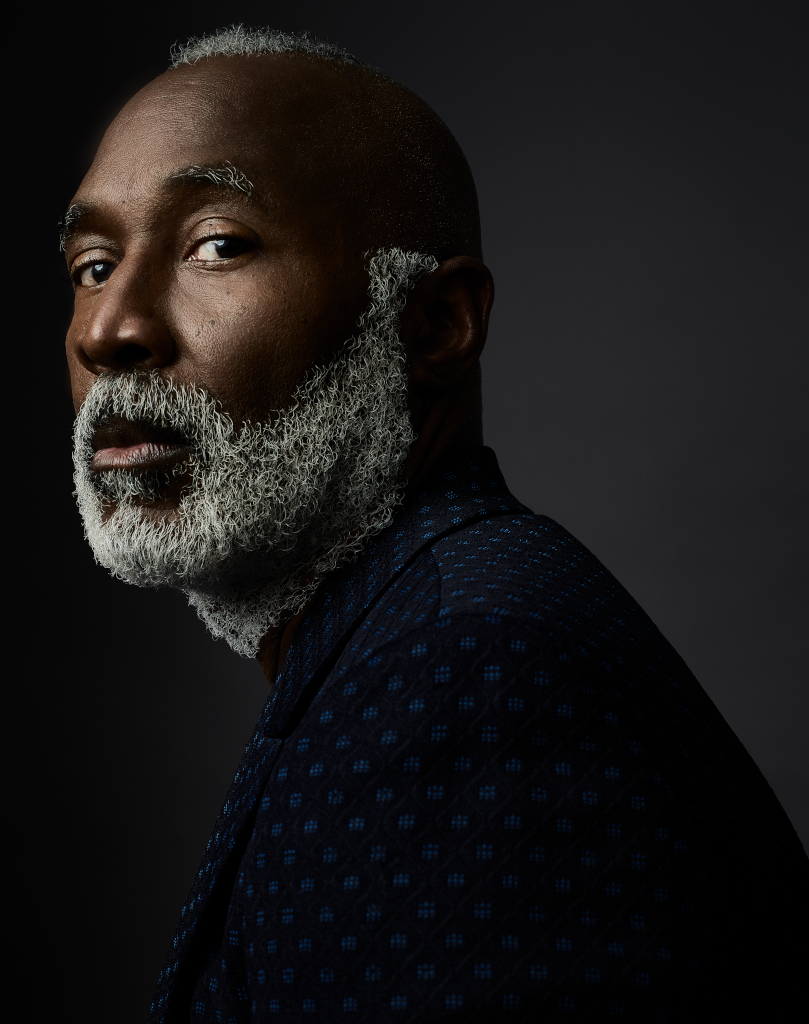

As an artist and designer who creates radically joyful and introspective works, Nick Cave is a leading voice in America today. To coincide with his retrospective at New York’s Guggenheim Museum and his new collection of textiles for Knoll, Dan speaks with Cave about his youth, how he created his first Soundsuits, his work with Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, and his ongoing quest to explore themes of social justice.

Nick Cave: Nick Cave is a messenger first, artist second, educator third, and that is the order in which he goes in. And I am an artist with a mission for change, equity, and inclusion. I mean, at the end of the day, studio practice is important, but it’s really bringing the world together and making way for a better existence.

Dan Rubinstein: Hi, I’m Dan Rubinstein and this is the Grand Tourist. I’ve been a design journalist for nearly 20 years, and this is my personalized guided tour through the worlds of fashion, art, architecture, food, and travel, all the elements of a well-lived life. And welcome to the first episode of season six. We have so many exciting episodes planned and I can’t wait to share all of it with you.

My guest today is my favorite kind of artist. His creativity is boundless. He’s equally daring and innovative, and his work carries deep meaning worthy of discussion and introspection. Team Magazine summed him up pretty well when they called him the most joyful and critical artist in America, Nick Cave. The first time I heard about Nick Cave was in 2013. As part of the centennial celebration of New York’s Grand Central Station, he staged a performance with a company of dancers from the famed Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, dressed in his fantastical sound suits. These head to toe costumes create colorful otherworldly characters that make sound as they move. It was an early social media sensation and in my mind ignited the current renaissance in performance art.

Nick Cave is also the subject of a retrospective called For Other More, which began at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago and is now up at New York’s Guggenheim until April 10th. There his sound suits are celebrated like towering sculptures alongside Early Works, video and other mixed media pieces that use found objects to create commentary on American culture and social justice. Speaking of social justice, one of his recent works is a massive installation where he plastered giant black type onto the facade of a school in upstate New York That reads Truth Be Told, more on that later.

Nick was born in Missouri and later attended the Kansas City Art Institute and then his MFA from the renowned Art and Design School, Cranbrook. As an artist I’ve always considered to be equally an incredible designer. He does teach graduate level fashion courses after all at the Art Institute of Chicago. His latest triumph is a line of textiles for Knoll, which pull inspiration from his portfolio, especially his sound suits. I caught up with Nick Cave from his studio in Chicago, which he runs with his longtime personal partner and also design director, Bob Faust. I wanted to learn about how he became the artist he is today, his club life in New York during the days of disco, and how one of his shows in 2018, If A Tree Falls, at his longtime gallery, Jack Shaman, seemed to foretell the Black Lives Matter movement.

Nick Cave: I think, when I think about the early years, it’s the liberation of being able to be creative and parents not getting in the way of that. With my mother and father, I think that they paid attention to what settled us, may it be sports or may it be art, whatever, and they understood that this what’s focusing this kid right now, and so, “He’s okay, he’s going to be fine. Let’s now focus on the other ones that maybe are not so settled in.” Kids tell you what they’re interested in if we listen.

So, you had six brothers. Would you have any sisters, or was it all boys?

All boys.

Oh, lord. Okay. So, if you had seven boys, I would assume that your parents would do anything to make sure everyone was happy.

That, and I think structure and unconditional love. My mother comes from a family of 16, so she was first of 16, so she already knew how to navigate and manage a group of young people. That, and feeling secure and feeling protected and liberated. I was just dressing crazy as a kid. My mother was all for it. Just these sort of things that she believed, “Well, as long as none of that gets in the way of your schoolwork, what does it matter?”

And were you the artistic one of your brothers?

No, I’ve got three other brothers that are artistic, Jack and then Don. One comes from a design field, corporate design world, and my brother, Don, works in the building industry. And so it was there and surrounded by aunts and grandparents that were makers, and I grew up around creative energy.

And when you went there, at such an early age, did you have any art heroes or people that you looked up to creatively where you were like, “Wow, that’s why I want to go to school, it’s because I want to be like somebody?”

I think as a young person, my first museum experience was when I was 17 and I went to the St. Louis Art Museum, and I saw this Kiefer painting and I started to cry. I don’t even know why, but I was very emotional, but I didn’t know there was such a thing as an art school. I thought you maybe did it in college at a university. And then Ms. McGrid, who was my high school art teacher, she was the one that says, “I think you should go into art.” And I was like, “Okay.” And so she was the one that helped direct that shift because she saw something there.

And was that energy supportive of you going to the Kansas City Art Institute?

Well, when I told my mother that this is what I wanted to do, she was like, “Okay.” With a bit of hesitation, like, “How in the hell is this going to pan out at the end? Where does this lead this young man toward toward?” But it was really, again, what I desired. I think that was the most important thing for her, is that, “But this is what he wants to pursue.”

So, when you studied at the Kansas City Art Institute, what kind of courses did you take?

Well, Kansas City Art Institute, liberal arts, and then your first year is foundation, so you basically are really learning about so many sort of methods and ways of working. So, I was really just absorbing all of the possibilities from sculpture, to performance, to painting and drawing textiles. And so, that was really the underlining, and also dance at the University of Kansas, Kansas City, in terms of thinking about electives and things of that sort.

So, I was really just getting my feet wet, exploring and looking at all these various disciplines and found that I was more comfortable in the textile and fiber program there. And so, that’s where I landed and that’s where I was making things, objects, and then was thinking about the body and how does that find its way into this practice. And so, that’s where performance came into play and thinking about happenings and pulling together classmates and creating things on the streets and just working in this non-collaborative way, thinking about, “In order for a spectacle to happen, I need bodies and what does that mean in terms of dress?”

So, I was really, really just exploring that vast kind of space from objects to the body, to performance, to public space. And so, that’s when it all started to come together, or me thinking…Not that I was really committed to anything, because I was still learning so much. I remember being a senior and I did my first mini collection, and Swanson’s, this department store on the plaza, we had open studio and they came through the studio and wanted this collection. Well, I’m like, “What does that mean?” And I did it, but it was not that I was like, “Oh, this is what I want to do. I’m going to be a fashion designer.” No, I wasn’t even thinking about it from that perspective as opposed to, “Oh, that was a great experience.” And I was able to meet and step up to the deadlines. And so, I was able to complete that project. And so, it was really project-based experiences that helped shape who I am today.

(SPONSOR BREAK)

And the New York Times wrote a piece on you a couple of years ago about your experience as a graduate student at Cranbrook, which of course is one of our great design-driven, I guess I could say, institutions, which is in Michigan for those who aren’t from the US, in the late ’80s. And you recalled to the journalist that you had this feeling for the first time of being the only black male in the program. And I’m curious what that was like at that time and how that may have impacted the way you saw yourself or the way you thought about your work.

Well, I think art school, ’80s, ’70s, if you had three to five people of color, that was huge. So, at undergrad, there was probably maybe six people of color there. And so you knew, it is what it is. And so I was able to connect and have connection at undergrad, but at Cranbrook, when I went, was the only minority. And I was like, “What?” I was literally quite shocked. And it was really the first time that I had to look at myself as a black man because there was no one that looked like me around me. And so, I began this journey of trying to address that.

I remember the first series of critiques and I was doing work about that feeling and no response was provided in the critique. No one would say anything about this work. And so my professor was just furious, like, “Nick has put this work out here and you all are not responding.” And I refused to talk because I thought, “I’m working through it through this application, and the least you can do is respond to what it is that I’m doing.” And so, that was interesting. and I was very much aware, very awakened in that moment, not that that was hindering my development there.

And then I realized that I was really…This is Bloomfield Hills, which is a suburb of Detroit and Detroit…thank God for Detroit. Detroit balanced it all out for me. I was on campus during the week, on the weekends I was in Detroit. I just needed to be with my people. It’s interesting how we figure out how it all is going to work out or what we need in order to create balance. And so that was extraordinary to be very much connected to Detroit. And at the same time, being able to get back to Cranbrook and push on through.

There’s no bio about you that doesn’t mention summer programs at Alvin Ailey and your time there. Can you expand a little bit upon that and what that was like? And I’m also fascinated because it was New York in the, I would say, probably early ’80s, early-mid-’80s, if I’m getting the time right.

Yeah, early ’80s, late ’70s. Well, I started dance at the University of Kansas, Kansas City where Alvin Ailey had a satellite program there. And so I was looking at dance, not that I was interested in going that direction, but how will it serve my practice? So, I was looking at it the same way as I would be looking at painting or sculpture as another discipline that I found that was very much part of what was needed in my work. But New York, at the time, it was the disco era. It was transitioning into house. And so I was completely in that world.

Okay. Where did you go out? Where did you go out for house music?

Oh, my God. To Limelight, to, oh God, the Underground. I’m not a drinker, I’m not a smoker. I don’t do any drugs or anything, never did. It was about having this space to release, to let go of all ambitions, to work through the shit. And I would literally jump into these clubs one o’clock in the morning and I would go right to the dance floor and literally dance till six in the morning, walk out the door, go to work, whatever was happening. That was the most healing time for me. It was a way in which I was able to figure out the sense of balance and clarity.

That brings us to the sound suit. I think the first one was in ’92, if I’m not mistaken. And if you could take us to that origin story of how that happened, I would love to hear it from your own mouth.

Well, I think after grad school, I was my closing meeting with my professor. He goes in, “By the way, you have a teaching position at the school of the Art Institute in Chicago.” And I was like, “Okay.” So that’s how I got to Chicago. And that year, Rodney King happened. That was the first video. I mean, it’s not that we as people of color, were not aware of these concerning incidents with police and people of color, but this is the first time that we all saw it recorded. I’m moving through the world thinking I was completely wide awake, but that incident awakened my consciousness in a way that shifted everything for me.

And so I’m sitting in the park really trying to process what we had just saw, and thinking about what does this mean for me as a black male of color, thinking about being profiled and just really trying to work through it. And then, as I was reading about Rodney King and how they were describing him larger than life, working out with prison weight, scary. And I’m imagining what that looked like. And so I’m thinking, “Wow.” I never have personally felt being discarded, dismissed, viewed less than, but I can certainly understand it.

And I happened to be in the park and I don’t know, I started collecting the twigs in the park and then I went back home and got my cart and came back, and that’s what I did for three days. I don’t even know why, but I think I saw that object as something that was discarded that I could kick out of the way and dismiss. But I went home and started to build what I thought was a sculpture, but then realized I could put it on. And then the moment that I put it on and started to move, it made sound. So then that, because what I was creating was trying to create anything to protect my innocence, to hide my identity, to shield my pain.

And so, when I moved in it, it made sound and that led me to think about ideas of protest: in order to be heard, you got to speak louder. And then, I didn’t know what I had made because it wasn’t that I went home and did a sketch. I just made this object. And for probably the first six years I had made this collection of sound suits that I basically just kept in the closet because I really, when I saw the twigs suit, I knew that something was about to shift in my life when I saw it. I could feel it, but I mentally was not quite caught up with it, with that body of work.

What was that moment when you…I’m sure you got feedback from somebody where you were like, “Oh, I’m on to something. This is something I need to go further in.”

I didn’t even share with anyone. I kept it to myself for about six years until I understood what I was making and why I was making it, and then the moment that I shared it with a gallery, that was my first show. Everything happened all in that moment.

It came out fully formed in the moment of, well, from the gallery’s point of view, it all had been in hiding for so long?

Yeah, and that year, I was on the cover of a magazine, just things that I’m like, “What is happening right now?” And so—

How did you cope with that?

It just was like, “This is coming.” And I just had to process and do the best that I could do. The one thing about being an artist is that, and a young artist, you’re not left out of school with a manual of how it’s done or how to do it. It will just happen in the moment or it may not happen. We don’t know. Preparation meets opportunity. I just truly believe. And so I was showing the work. I was like a gypsy, artist gypsy. I would show the work here, pack up, keep it moving, show over here, not committed to any gallery, not so sure what I wanted still, but very committed to making, all in or nothing. And so that went on for about, I would say, six years until Jack Shaman came across the work.

How did that happen if it was kept private? How did that—

Well, a friend of mine was going to New York and said, “I think there’s this gallery that I think would like your work. Put together a portfolio and I’ll take it there.” Because that’s what it was; it was a portfolio back then.

He didn’t check out your Instagram, is what you’re telling me? Yeah. Okay.

And so Jack called me a week later and said, “We’re interested in your work.” And I was going to New York the following week, and I was like, “Okay, great.” He goes, “We would really like to sit down and talk to you.” And I was like, “Sure.” So, I went to New York, went to the gallery, didn’t tell them it was me, just to get a vibe of it and how did my body feel being in there. And then I left and came back home to Chicago. And then I called him and he was like, “Are you with a gallery?” And I said, “No.” And he was like, “Really, why?” “I just haven’t found the right connection, the right partnership. And so I’m just waiting until that comes.” It’s like dating. It’s the same thing.

And why was the gallery and Jack the right partner for you?

Well, they asked the right questions, I think, from the beginning. So they were like, “Can we fly you to New York and meet with you?” And I said, “Sure.” So then I went there. “We’re very interested in the work, but we’re more interested in what do you want for yourself.” And that was the moment of truth, like, “Oh shit, I have to tell them what I want.”

What did you want back then?

To be a famous artist, that’s what I said. And they said, “Okay, we’ll work with you to get you there.” That moment was enormous for me, because I had to say it. When you say your truth, somehow it puts it into the universe in a way that it validates, it just allows the mission to now be developed or pursued. And so that was the beginning of our journey.

(SPONSOR BREAK)

And I think for many people, especially in the broader culture at large, the Herd New York performance at Grand Central Terminal was such a major moment. And I remember being in New York at that time and it being the total talk of the town, and it was early social media days and it really became this spectacle that everyone was talking about, and touched a nerve. And so, when it comes to working with these performers, as you mentioned, like working with people locally, which I’m sure in New York is a little bit maybe easier to do, there’s just a lot of people and a lot of talent, when you’re working with these dancers…You mentioned really diving deep into a locality and the people there. But when you’re working with these dancers and practicing, how do you work with them? What is that process like? How much of your own artistic intent do you try to imbue into them? Or what is that like?

Well, I will bring on a choreography. We’re working with musicians, vocalists as well, and then we’re in a one-to-two-week residency building a project. And so that’s what we do. So, like Herd New York. I wanted to work with the Alvin Ailey School, and so we worked with them, we worked with a number of local musicians. And then we went into this residency and really talked about the intent, the purpose of Herd, and getting us back to this space of imagination, dreaming. Herd came about because as a kid, what allowed me to dream was when my mother took off my sock, put it on her hand, and all of a sudden it was a puppet. I was literally transformed. And so that was what that moment was about. How do we get ourselves back to the space of dreaming? Dreaming, for me, has always been hope.

And what do you dream about now?

And again, all of these projects, performance-based projects, it’s really all about inclusion. It has always been about this collective bringing people together that aren’t familiar, that don’t know one another, and how do we collectively build something that will affect, that will change how we see ourselves. And so I think as an artist, I’m always very much thinking about service. How does my practice serve the larger community? How does it make an impact? How does it inform a way of existing and being?

And taking that idea about artist communication to another level, fast forwarding to somewhat recently with your work, Truth Be Told, that has this very raw, immediate vibe to it, can you describe what that first iteration of it was and how it was received and how it came to be?

Well, Truth Be Told, that was that George Floyd period, that was COVID period. That was the dismantling of all the Confederate statues. So, there was a dismantling of institutions and corporations and how were we going to move ourselves forward with equity and equality. And collectively, we all knew that there was so much work that needed to be done. And then, we were also dealing with an election where…I’m sorry, but race was in the center of a very complex and difficult moment. And so, I was doing work here at Facility, which is the building that I own, in response to George Floyd and using the facade of that space, and what am I accountable for in this moment and how can I be proactive.

And so, I was also in that process of asking, “What is the role of the gallery? What stance are they taking?” And so I talked with Jack about a number of projects and asking him, “You have a staple of people of color. What does this moment mean for you? What do you have to say about it?” And so, working with him to do this public art piece, let me tell you, not having any idea of the magnitude that came out of that project…With all of these public projects, I have no idea what the end results are going to be, what the outcome is going to be. I’m gambling all in or nothing.

Your 2018 show, If A Tree Falls, which if I’m not mistaken, didn’t have sound suits or things like that and it was a more heavier show. Obviously, it came in 2018, pre-pandemic, pre-George Floyd. But now when you look at it, it seems like you are Nostradamus of American politics in a way.

It’s crazy. And that show came about as I was out thrifting, antiquing, and I came across this ceramic container, figurative container, of a black man’s face. And it was very interesting to me. And so I grabbed it off the shelf and I proceeded to read the description, and it says, “Spittoon.” And I was like, “OMG, livid.” I was like, “Oh, my God. Oh, my God. Oh, my God.”

Antiquing can be a really damaging experience.

And that was the catalyst for that show. I then went around the entire country collecting the most repressive, the most despairing artifacts that I could find, such as a black man holding up the seat of a piano stool. It was this-

It’s the, what do you call it in…There’s an Italian eight genre of furniture and objet of the black servant holding a tray of fruit.

Right. Well, and that’s what I started to think about, was just how racism found its way into consumerism and product. And it was just fascinating for me. So then I was just searching for all these objects and created this takeaway newspaper that you could take as you view the show, you would walk away with this newspaper about the object, where it was found in the country, and just created this whole narrative around that and worked with a couple of writers, writing about kitchen and the black nostalgic objects that provoked this messaging. And so, it was just interesting to think about that. And again, just allowing these sort of moments that trigger and shift the direction of the work, but feeling that I have something to say.

And now, at the end of 2022, four years later, so much has happened since that show to now look back and to see this…Well, not a complete arc, because of course, you’ve been working for a very long time. But Rodney King, George Floyd, pandemic and everything in between to today. How are you feeling about the state of the culture now?

I think with this survey show that just closed here at the MCA, traveling to the Guggenheim, it allowed for me to realize that for almost four decades, I have been trying to bring light to the subject of racism, inequality, injustice. For me to reflect on that work and to realize that that’s what I’ve been doing is like, “Wow.” So, I understand purpose. But what came out of the George Floyd, for me, was I had this awakening that this systematic racism is designed to keep people of color in this state of trauma. And I was like, “Absolutely not. No, no, no, and no.”

So, it shifted my structure in the studio back to the origin of where the practice started, was from this place of naiveness, this moment of talking about black love, family, family structure, and pulling from this other way of operating. And so now, the practice is back to that space of discovering who I am, because I’ve been so consumed about working under this one vernacular that I am like, “Who am I? If there wasn’t racism in my existence, who would I be? What would I be making?” So that’s me going forward.

Well, speaking of what you’re making, this might be either the perfect transition or the world’s worst transition to your collection of textiles with Knoll, which is…how’s that for a segue? Boom, done. Okay. Okay. So, how did that happen in the middle of all of this? I’m sure you’ve been working on it for a long time, and then you’re doing this, Truth Be Told, and this heavy period, and pandemic, I’m sure. And then someone says, “Hey, how about a faux shearling?” How did that happen? Because it’s so amazing.

“How about a tapestry? How about some upholstery?”

Let’s talk drapes.

Let’s talk—

Let’s talk drapes.

Let’s talk upholstery.

Speaking of joy.

It was an ask that was about three years in the making a, but it was really…Again, coming from Cranbrook, I’m surrounded by Serenin, I’m surrounded by Knoll’s design. I’m just like, “That’s the landscape of that school.” And so that was interesting to me, that connection. But then what was also interesting for me is just the translation of the artwork into a textile. I come from a textile background. I understand weaving. I understand your cards, I know how to do that. I understand prints, I understand repeats. That was part of my undergrad upbringing. So it made sense. And I think the most important thing with Knoll’s textiles, as well as any of the work, any shifts in the work is translation and probably the most important thing is the essence. How do I transfer the essence of my practice into a collection for Knoll? And so that’s really what I focused on. I mean, the collection’s fabulous.

And how long did you work on it?

For about three years.

Oh, gosh. Okay. Wow.

Samples, and, “That’s not working. Let’s go back to the drawing board.” Until it all came together. And again, it has to read Nick Cave for Knoll.

And that’s why you paired each one. Was that idea from you or from Knoll, the idea of pairing each design directly to a piece of work?

Well, I think it was just, again, us collectively in conversation that…The first phase was me pulling together about 50 images of my work, sending that to them as they started to think about surface treatments. What is going to be upholstery? What is going to be drapery? How do we divide up and create these categories based on the artwork and where they feel that it fits? So, you’ve got upholstery, you’ve got drapery, you’ve got wallpapers, and then again, just…And I’m thinking in my brain, “Texture, texture, texture, texture.” Because that’s really, at the end of the day, the foundation of my work. It’s really about texture and pattern and color and exuberance and…yeah.

Well, one question I did forget to ask, which is about your partner Bob and how he’s a part of your life and your work there at facility. And I’m curious, how did you guys meet?

We met, I was having a sweater sale, and a friend of Bob’s brought him to the sweater sale.

What year was that?

Oh, God, maybe ’84, ’85 maybe. But we met at that time and I asked him what did he do. He goes, “I’m a designer.” And I said, “I’m doing my first solo show and I need a book. Do you want to design the book?” So, that’s how we met. And we worked from that year till today, where the first 10 years, friends, no partnership at that time. But we made a book every year.

Oh, that’s so sweet.

And we just were amazing friends. He was probably my best friend. And so, we really had this amazing friendship and amazing work relationship around projects.

And after all this time, if you went back in time and met your younger self in 1991, a year before you made that first sound suit, what would your younger self ask you now and how would you respond? What would be that question and answer echoing through time be like?

I think my younger self would say to me, “Thank you for not losing perspective, not losing hope and staying your authentic self through art.” It’s interesting. I think about that, and I just was looking at some pictures when I was 19, and I’m thinking like, “Wow, I still have that drive. I still have the hunger. I am all in as I was all in then.” I am completely so all in to creativity and fortunate to be still fully committed to the practice and the mission.

And what’s next for your studio?

It’s interesting. Well, this shift of…I’ve been able to go back and forth to this retrospective at the MCA and I can close that chapter. So I’m in the midst of, I’m working with a number of fabricators, building the materials for the next body of work.

Do you find it difficult after you’ve gone through a big retrospective to be like—

It’s going and it’s scary, and I don’t know what I’m doing, but I have to do it.

And what gives you that artistic bravery?

I’ve always been brave. If I’m not scared, then something is…It’s never been easy. I’ve always been willing to step up to fear, because that really has always been the driving force that has always prevailed me to move forward. But I don’t know, I’m watching all this preparation being done around me, but I’m like, “Oh my God, I’ve got to step into this at some point. It’s all being delivered any day now.” And Bob’s like, “What are you going to do? What are you thinking?” I’m like, “Don’t talk to me about it. I can’t. I’m not there yet. It’s going to happen. I don’t know what, but it feels right, but it feels…I don’t know what it feels. I’m scared, but I am willing to go all in.”

A special thanks to my guest Nick Cave, and to Bob Faust and Knoll Textiles for making this episode happen. The editor of The Grand Tourist is Stan Hall. To keep this going, please follow me on Instagram @danrubinstein to learn more and sign up with your email for updates at thegrandtourist.net. And don’t forget to follow The Grand Tourist on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you’d like to listen. And leave us a rating or comment, every little bit helps. Till next time.

Plus, an exciting young British artist receives a retrospective, Marcel Dzama's whimsical drawings take a political turn in L.A., and more gallery openings.

Through her books and products, this 21st-century domestic goddess is truly a part of the classic American style firmament. On this episode, Aerin Lauder speaks about growing up with her grandmother Estée, what she's learned over years of being in the business, and more.

The best of museum openings this week, from Barbara Kruger’s words landing in Bilbao to Jenny Saville’s fleshy nudes coming to London.