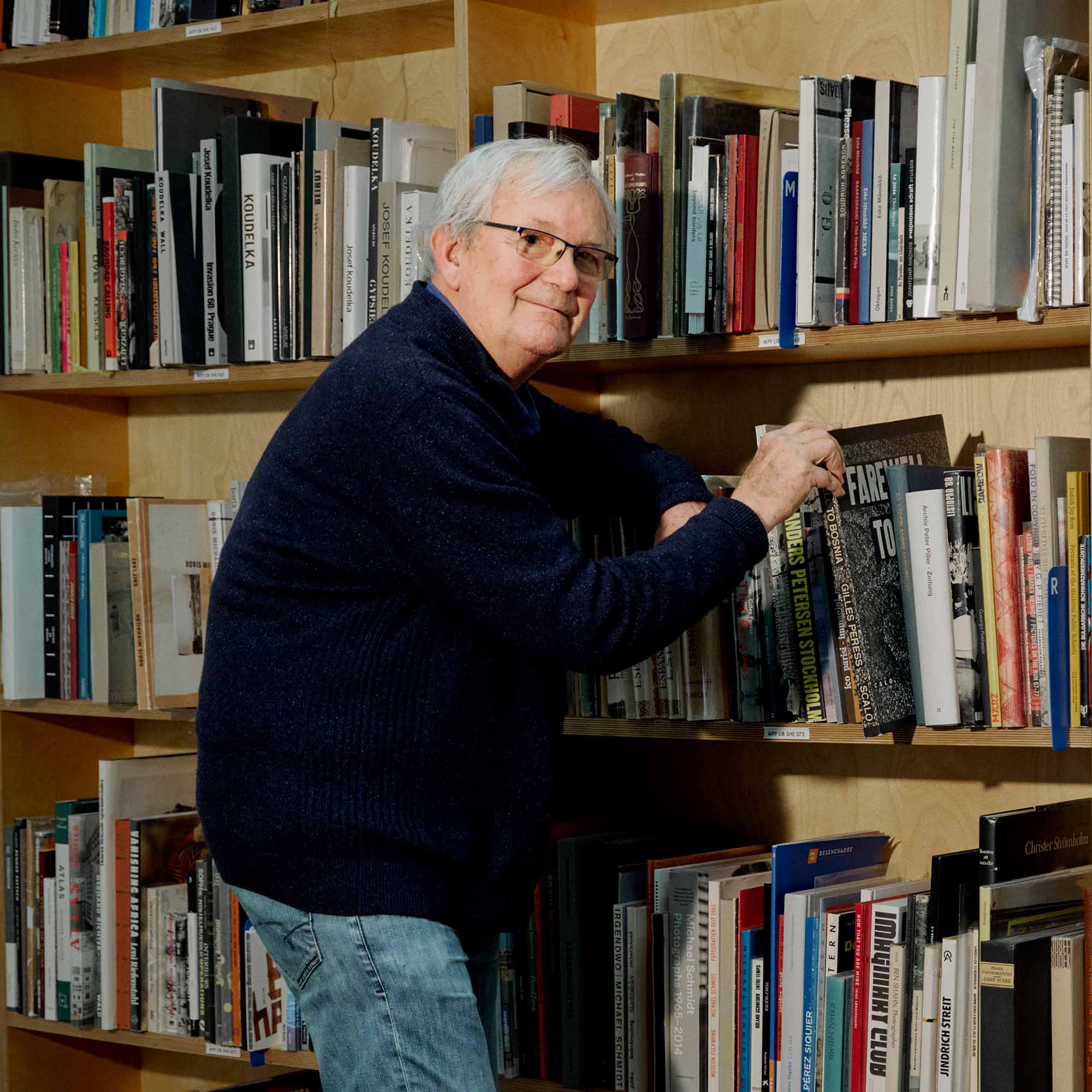

Martin Parr: A Photography Great Who Turned a Lens on Society

British photographer Martin Parr knew how to observe and highlight aspects of culture and contemporary life in both humorous and refreshingly honest ways.

This article is from our first-ever print issue, available for order online now.

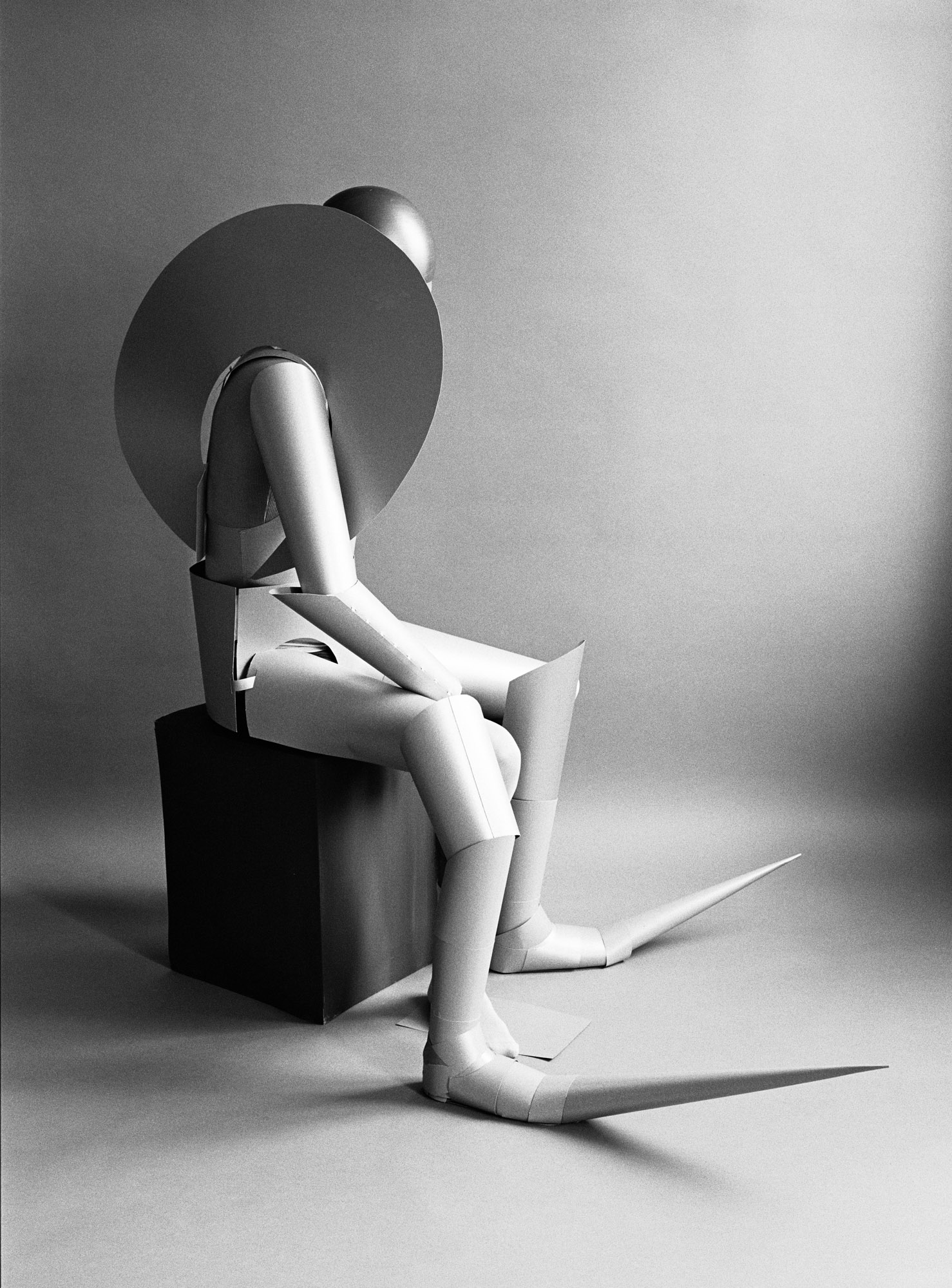

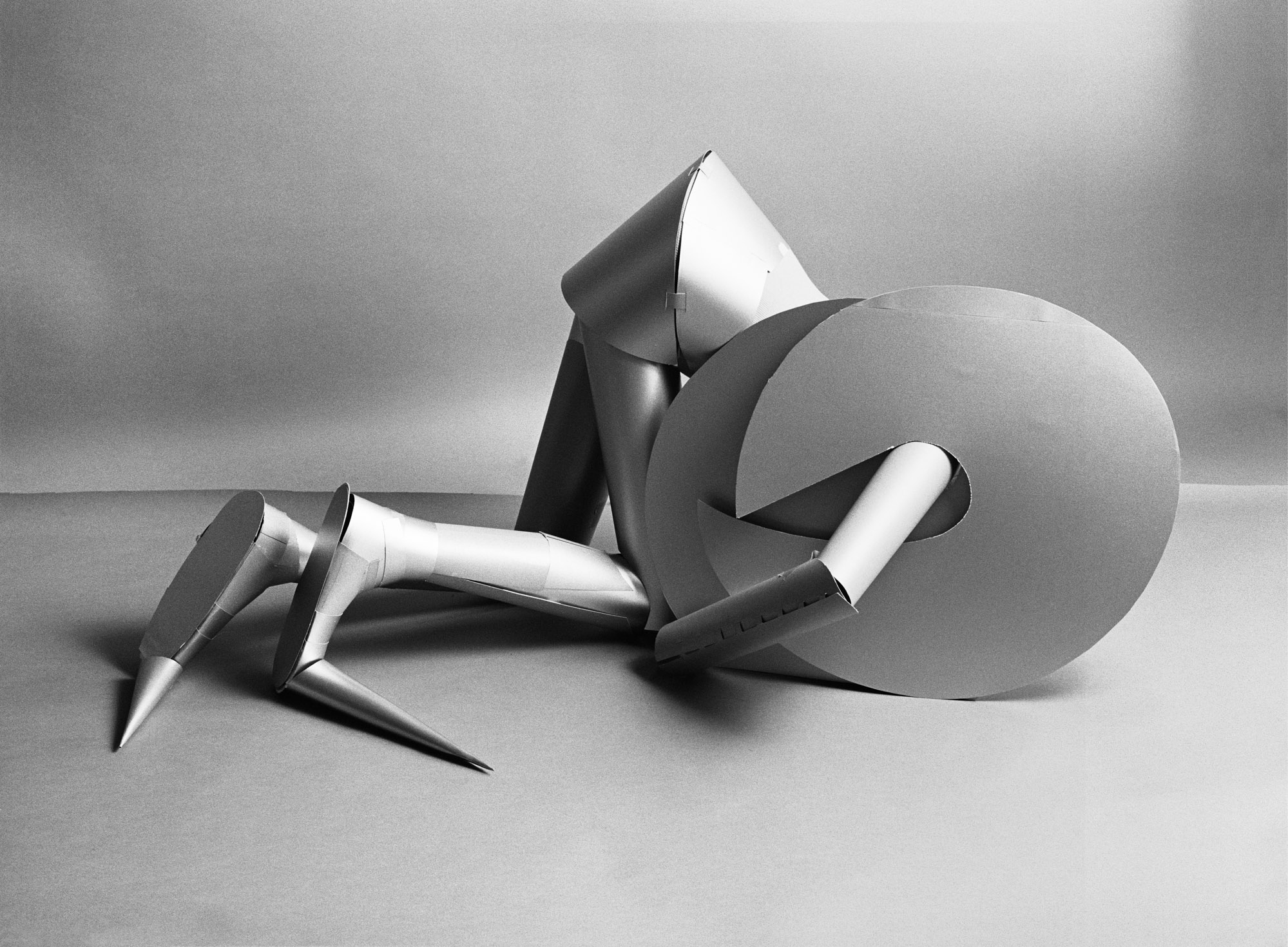

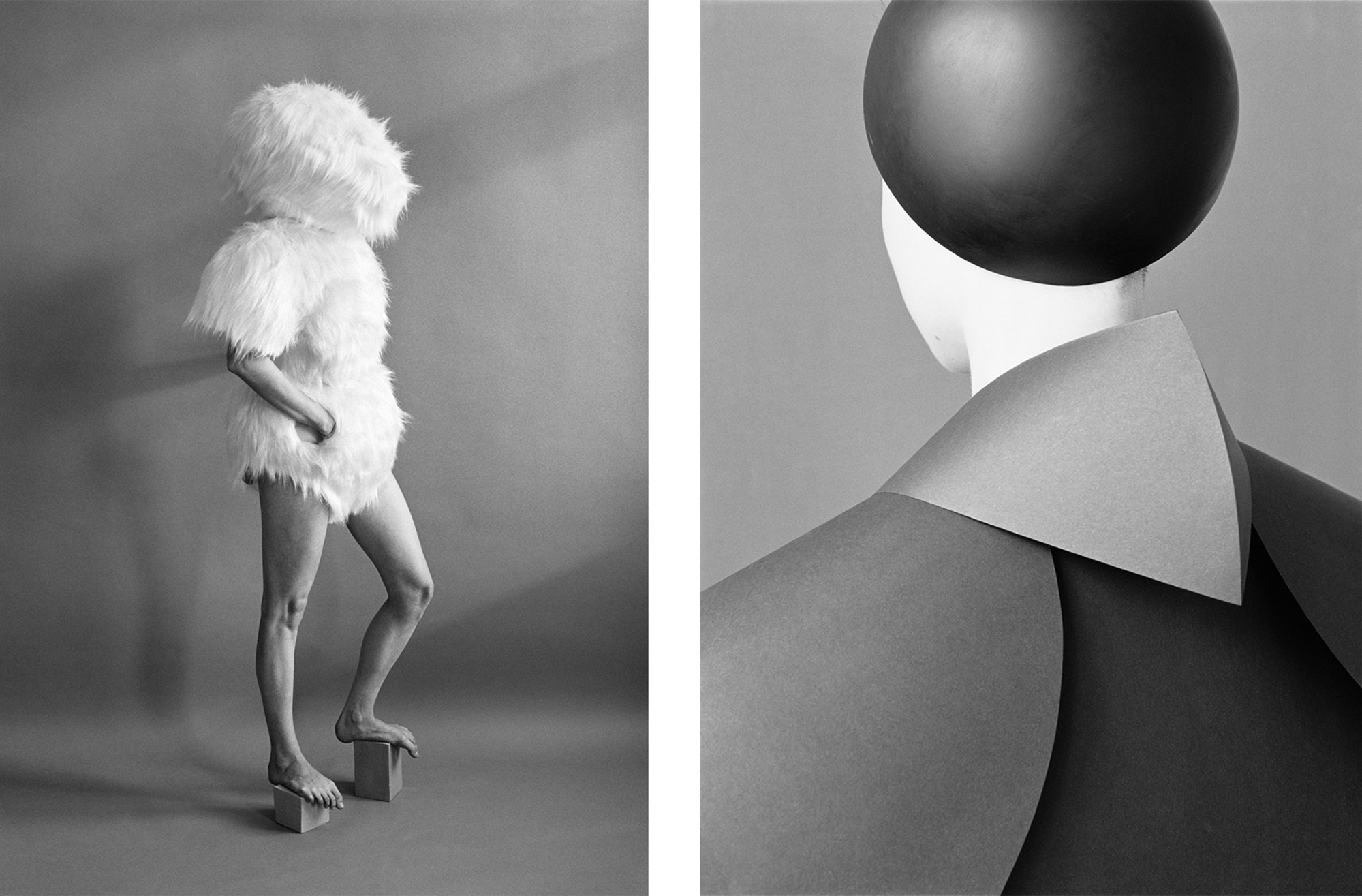

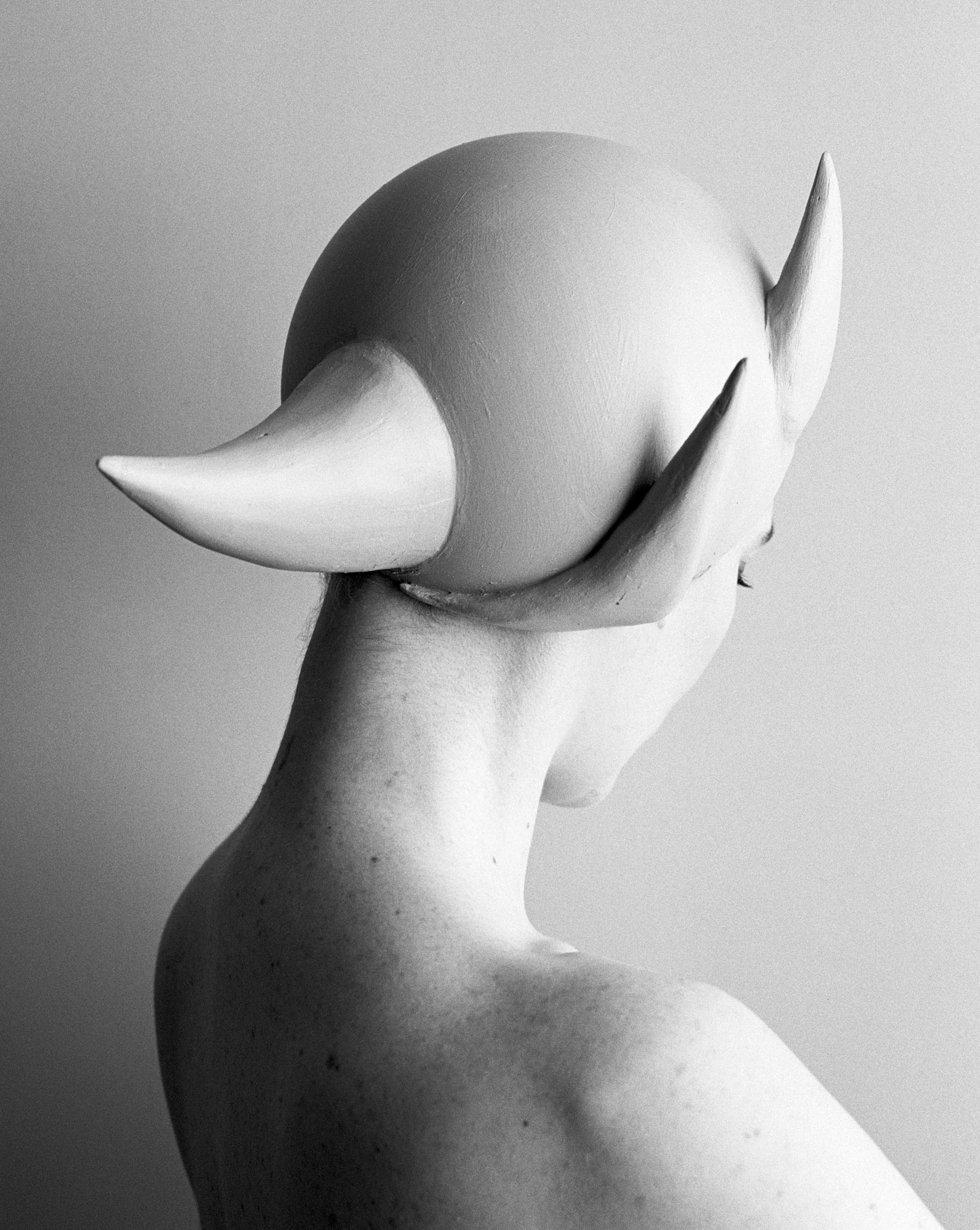

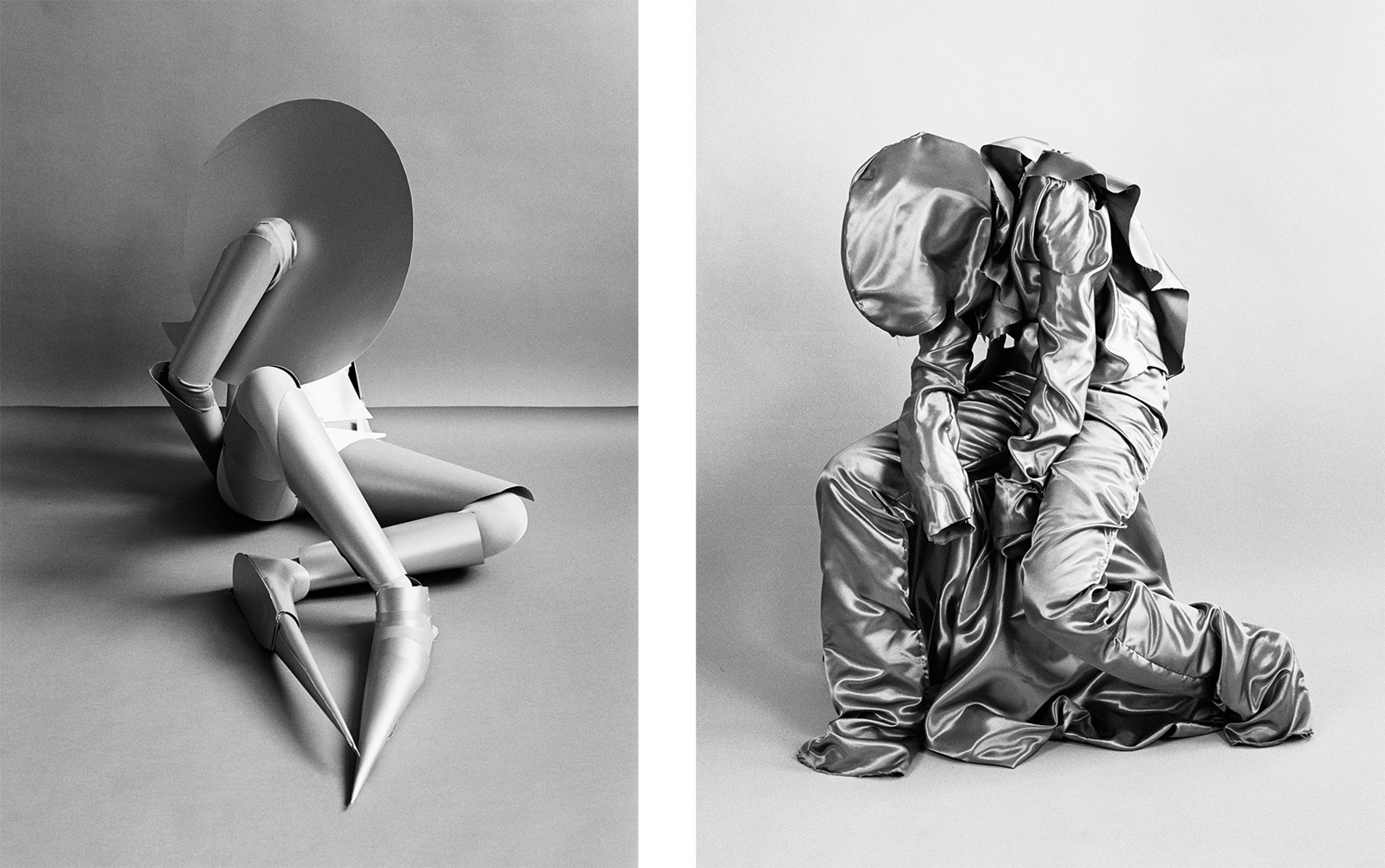

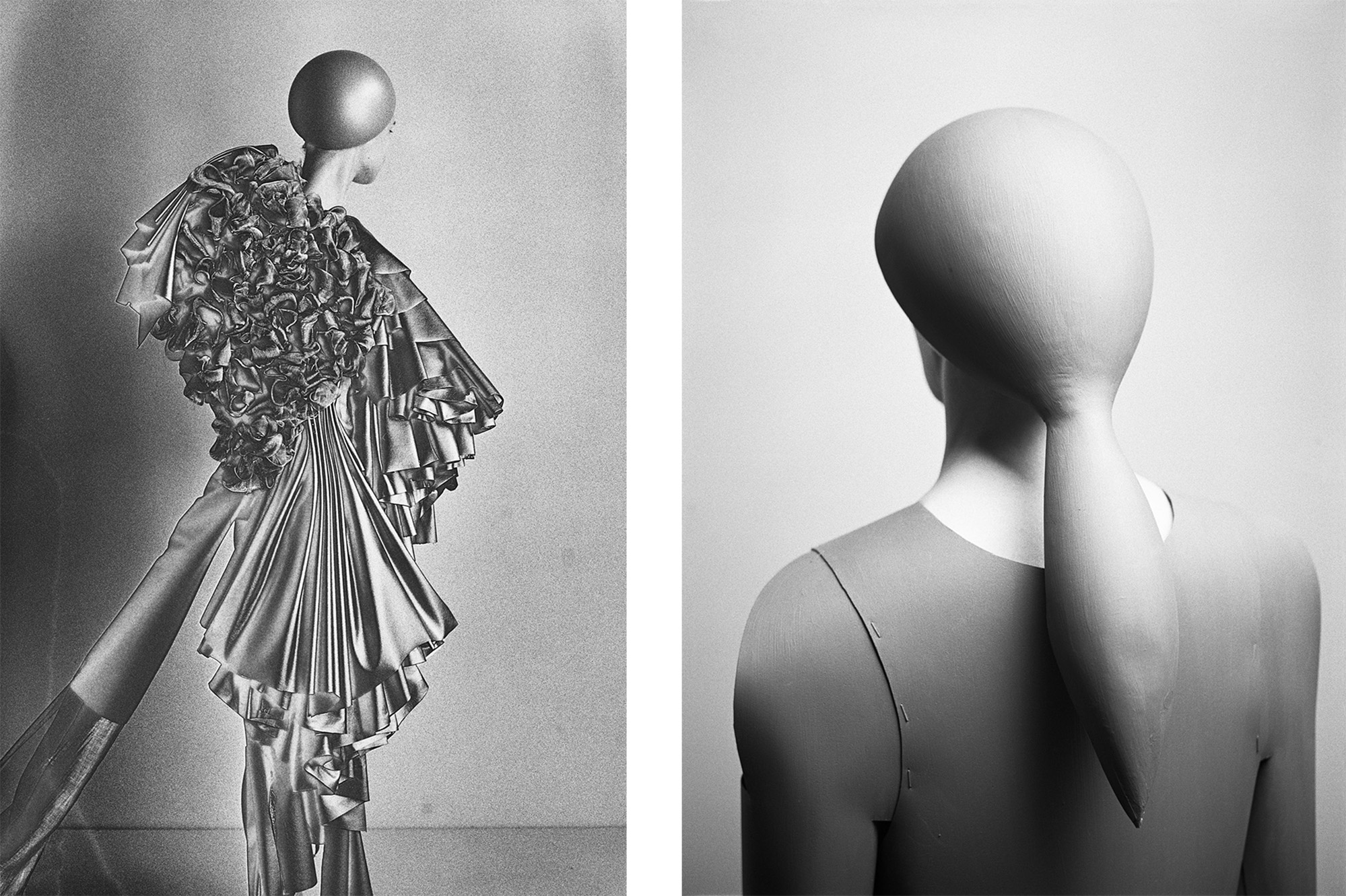

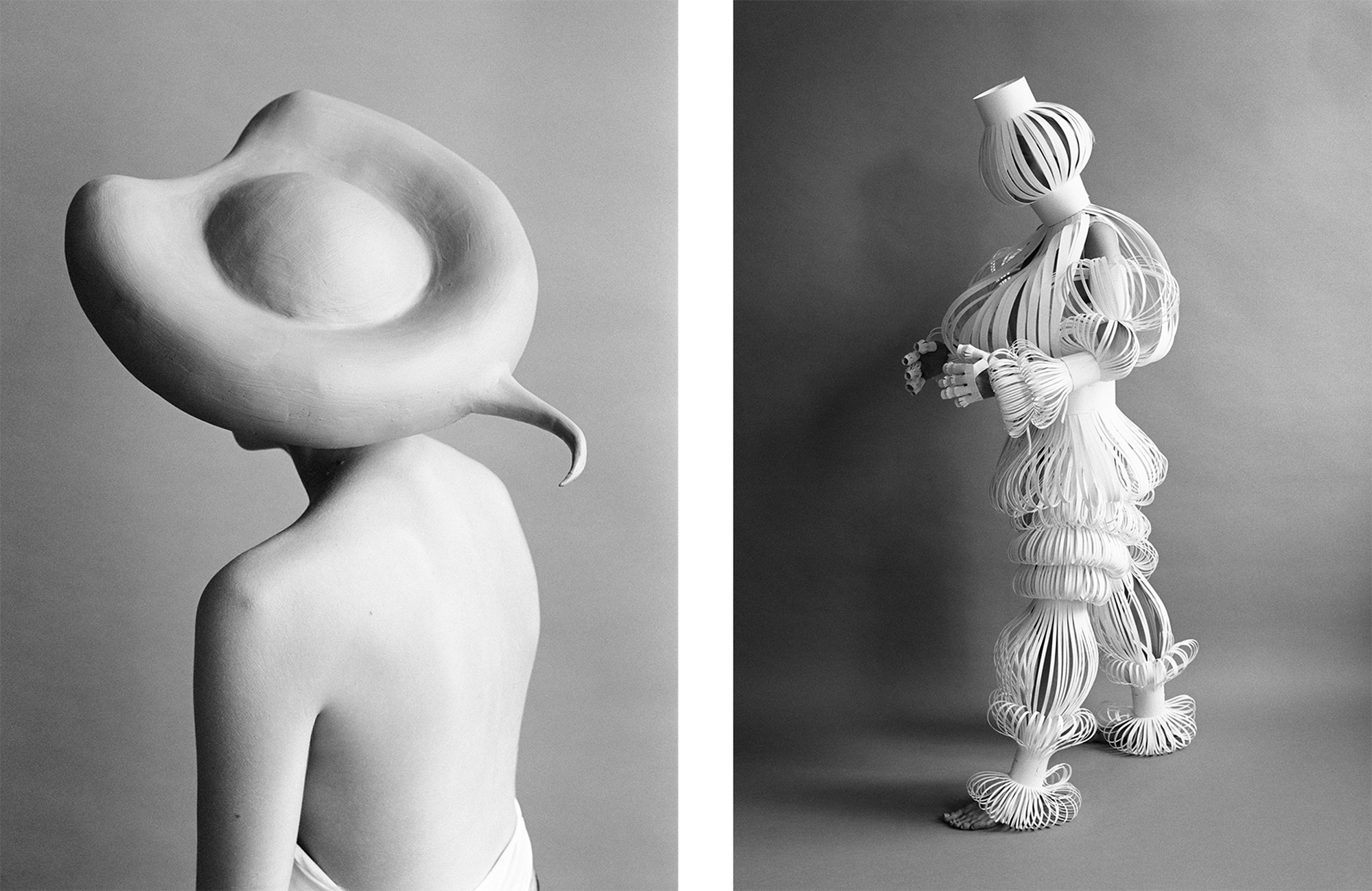

For the Vienna-based artist and photographer Tina Lechner, the female form has been a constant source of inspiration since she began her studio-based practice in 2011. A graduate of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, Lechner’s methods are pleasingly long-form. She skillfully handcrafts headwear and costumes, which she applies to the head and body as adornment—a kind of sculpted armor, if you will—and then photographs her posed subjects. The enigmatic images explore female identity, expressing both the strength and vulnerability of womankind, which she documents mostly in black and white. There are lightest-touch clues to Lechner’s early career in commercial graphic design in both the clarity and simplicity of her aesthetic, some of it recalling classic fashion imagery, but it’s the application of analog techniques using film with a medium-format camera, as well as hand-printing her own images, that give her work true depth. Add the retro-futuristic, somewhat science-fiction style, and her work becomes a little disorienting, haunting in parts and hard to time-stamp. This fall, following a two-year hiatus where she worked solely in her Vienna studio, she is presenting a new series of work in a solo exhibition at the Mobius Gallery in Bucharest, Romania. I spoke with Lechner about her meticulous practice, and what this year holds for her.

Tina, tell me a little about your background. Was your upbringing steeped in creativity?

I spent a lot of time with my grandmother as a child. She had a tailoring business. It was fascinating for me to be with her in her house, as it was full of beautiful garments and dressmakers’ dummies. She had clients that came over and ordered some really beautiful clothes. For me as a child it was so interesting to see how those people bought a dream when they had garments designed for them; it felt like a whole other time back then. We didn’t have mass consumption, and things were produced by hand, so when you bought something it was meant to be kept forever.

Were you raised in Vienna?

No, I was raised in a small village called St. Pölten, an hour from Vienna. My full-time life was in the countryside, so we hardly came to Vienna, maybe just to visit museums. For me, my grandmother was more the big inspiration, specializing in festive clothing, creating everything herself, which meant I picked up a lot about pattern drafting that later on I applied to my own work. My whole family was very open to creativity though. My mother was always painting; it was her passion. So that was really my starting point. But then, as most people do, I moved to Vienna after school.

What brought you to the city?

I studied graphic design and wanted to work in that industry, but soon discovered it wasn’t enough for me because I wanted to realize my own artistic projects. The design I was doing for magazines and catalogues was so commercial, so I did it for a few years but became fed up pretty quickly. This is about 20 years ago now. If I think about it, I was the first laptop class, the first computer class for graphic design. I had school for two years, and I worked in a job for three years. After that, however, I knew I wouldn’t survive doing that my whole life.

How did you make the transition to fine art?

We have two big art-led universities in Vienna—it isn’t that big a city, but there are a lot of opportunities here. Back then, there were little shops where you could buy camera film and photographic paper. I found an old camera, bought the film, and that was it—it was love at first sight. I started photographing three or four months prior to starting my studies.

At work there was a box under the desk where I rested my feet, and one day, I opened it and there was an old camera inside which wasn’t used anymore, a Nikon small-format camera. I started to use it, to experiment and play. I then discovered the work of the American photographer Francesca Woodman, and that was it.

So you enrolled in a photography course at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna. What was it about photography that ignited something in you?

I was in love with analog photography because you could do everything yourself, from film developing to the final print, so you didn’t need anyone else. I experimented a lot with papers and chemicals and the solarization process and so on. So many of those materials I used have vanished, though. It can be hard to get supplies. At university, I spent endless hours in the darkroom—I think I was one of very few people still using it. Why photography? I was always very fascinated by the flat image. For me it was like I could include all my ideas. I had the feeling I didn’t need anything else.

Was it during your studies you honed your style?

Yes. I started staging photography, and because I always needed props I went to a place where you could rent things for films. It became very expensive for me back then. I was in my late 20s, but I soon realized I was very good at building those things myself. It was a magic situation, working out I could do it. Also, at school you can try different classes, from sculpture to painting and so on. I also think one of the most important things you discover at university is learning from your friends and other students. They make you grow; you grow together. I remember some of my classmates started very young and didn’t really know what they were looking for yet. I had my vision, and I was working a lot, and it was a very good time. I was there for five years. I graduated in 2013 and began working with a gallery straight away. We did a lot of exhibitions; I traveled a lot.

What’s the art scene like in Vienna today?

There’s a really good scene here. There are a lot of very good museums, galleries, young galleries, fairs, and art spaces. As an artist you have to participate somehow, otherwise you’re not seen. There are many possibilities and opportunities, and yeah, I think Vienna is quite interesting. I collaborated with an artist friend of mine a while ago; she’s a photographer, too. And I used her objects as costumes for my work, which was very nice, and we explored. For me it was the first time because usually I love to work on my own—I’m not a big group person, I have to say. I prefer to do my own projects.

Where do you work? Can you describe your studio setup?

I’m in my apartment, which is also my studio. I don’t separate the two because I always start to work here no matter which studio I have—it’s deeply connected to my life. I hate to go out in the morning, go to a studio. But on the same street I have a little darkroom, so I’m printing a bit there, and it’s also storage. I love natural light for photography—I think you cannot fake natural light. There’s an office building on the other side of the street, and it reflects the sun the best possible way to come into my studio; it’s like the best soft box ever. I can’t fake that with any artificial light. I try not to work in a perfectly prepared studio space because I have the feeling that it takes a bit out of the magic if you stage it too perfectly.

What does your creative process look like?

The starting point is always a sketch. I draw a lot, so I keep a sketchbook. In fact, I’m drawing all the time, and I work in series. I have different series ongoing, like those still-life images with props and the portraits and the textile works. And when I’ve decided to do a certain work, I decide which material to use, and then I start building or making. And then there’s a decision about which models to use. I work with different people. Sometimes I work with friends, students, or even dancers. Depending on who I work with it’s a completely different dynamic, of course, because with friends you can work differently. And if there’s a dancer, you find a completely new dimension in the work.

Can you talk a little about the props you create? Is materiality a starting point?

Sometimes it starts with the material. For example, I was working with faux fur, so the texture was the most important element of the object. Because I like to sketch, I think a lot about what’s the best way to work. In my new series I’ve used a Balenciaga wedding dress that I dyed black. It’s transporting all of those ideas like happiness and marriage and freedom and luck, and I transform it into stiff armor, which you can’t move a lot anymore. And I’ve crafted a helmet; it’s like a helmet for whatever you need in your life. I’m borrowing a lot from the fashion world. In the new pieces there are long pointed shoes, like armor for the legs, which are made from silver paper. The satin pieces are sewn by me—I watched my grandmother a lot, so I know how to do it. The lantern-like piece is from a children’s book of how to build paper costumes.

You always work with women in your images. Why is that?

I work with women because I use them as an extension of my body. In my early work as a student, fascinated by Francesca Woodman, I started using my own body before I used models to photograph things. My self-made costumes and their themes are closely connected to the female body. As a woman, I explore the specific needs, boundaries, and vulnerabilities that affect women. For me, the combination of vulnerability and strength can only be authentically expressed through working with women: isolating, protective, and body-augmenting prosthetics, props, and costumes in the tension between utopia and dystopia.

My earlier work was strongly inspired by [the German Bauhaus artist and choreographer] Oskar Schlemmer’s idea to reduce the human to a shape and take away all of his feelings and the vulnerability. And he tried to elevate it to a harmonious overarching world of shapes, which was everywhere in my very early works. What changed a bit is that we have this kind of dark moment in some of the works, which I didn’t have at the beginning because it was very plain and graphic. Also, in the past year or so, I’ve had feelings of loneliness that I’ve tried to show. But that’s just a part of life we all feel from time to time. My newer works increasingly focus on the conditio humana, the human condition.

I’m viewing the women in your images as somewhere between human, alien, and animalistic. Some feel slightly sinister and then almost playful and humorous. Is that your intention?

That’s completely correct—it’s all about that. It’s a lot about the human condition and vulnerability and about protection. The human is always the center of my work, whether they’re actually there or not, because they’re the main character. I don’t know if you have the feeling, for example, with the still-life images that the human is still there—can you feel it? I find it interesting that in my still-life images the human form doesn’t disappear even when it’s not there. It’s not about the male gaze, though. I never wanted to explain it too much because for me it should be very open: It’s a protective surface, I never show a face. I always want to leave a bit to the viewer to make of it what they want.

It’s hard to place your work in the past, present, or future. What has been your intention with its timeless quality?

The way I’m working with black-and-white film and paper leads to this aesthetic of retro-futurism. I’m fascinated by the connection between nostalgia and a futuristic vision. And it allows me to explore societal themes, such as the impact of technology on humanity and the tension between utopia and dystopia, which is the space I want to explore in between. My work reveals neither a specific place nor time but can, in some ways, be associated with Donna Haraway’s “A Cyborg Manifesto,” a 1985 socialist paper that seeks to reject the separation of humans and animals, and humans and machines.

My work is perhaps situated at the intersection of post- and transhumanism, and recalling early science-fiction films. Alongside Francesca Woodman’s work, I’ve been influenced by photographers including Man Ray, Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Diane Arbus, Erwin Blumenfeld, and Claude Cahun. But I have to say I’m much more influenced by painting, film, and fashion—people like Rei Kawakubo and Craig Green—than I am by other photographers.

As someone who works with so many analog elements, what are your thoughts on AI?

So with the beginnings of AI, I have the feeling that I have to go back to the more handcrafted-looking things. I don’t know if it’s a stupid thought, but it’s changing so much at the moment. We had this art fair in Vienna where I got the feeling that people are more and more into painting, and they want to be sure that it’s done by hand.

I suppose, though, that we do have to adapt, and in time we’ll see how we can use AI as a tool. I have experimented to see if it might inspire me, but it hasn’t worked for me so far. But I don’t want to use AI to produce the artworks themselves—it doesn’t make any sense for me.

This fall you have a new show in Bucharest. What can we expect there?

I have experimented a lot for my solo show in Romania. It’s a gallery I showed at five years ago. There, Mobius Gallery opened a new space in the House of the Free Press [known during the Communist era as the House of the Spark]. For this exhibition I’m hoping to show some sculptural work for the first time, alongside the photography that includes still-life images and a few elements of color in some of the photographs. It’s been a very long process to develop something I’ve wanted to show. I’ve also experimented a little with video and my models moving, but I haven’t decided if I will show the films yet.

Can you talk about the decision to take your work off the printed page?

You have these thoughts from the beginning when you start building sculptures and taking pictures of them: You have the sculpture in the studio and people visit, curators visit, and they always ask you why you don’t show them. And I had the feeling they don’t need to be shown because everything’s there in the image. But times have changed so much, and I think people need more. It’s good to show them a bit more, but perhaps different things, something three-dimensional. So I’m producing textiles, like soft sculptures in life size. My concept is to show mannequins I’ve built in the center of the space, hanging from above. I’ve worked with plastic leather, a very thick strong material that can be sculpted.

Do you feel like your latest series takes you in a brand-new direction?

In the past it was very precise. There were not a lot of possibilities for movement because of very stiff costumes that just required seeing the shoulder or face. With my newer work, I’m exploring the moment of vulnerability and pain to find this little moment to capture it, and it’s much more open than it was before. It’s more angular, perhaps reflecting the sharper world that we’re living in now.

British photographer Martin Parr knew how to observe and highlight aspects of culture and contemporary life in both humorous and refreshingly honest ways.

One of L.A.'s architectural treasures is taken over by an artist that uses color and design; India Mahdavi creates outerwear that makes rainy days a joy; and Jeanne Gang builds a recreational center in Brooklyn that's sorely needed.

One of the most exciting parts of traveling today? The ability to disconnect. On this episode, we explore Ranchlands, a massive land management business in the American West that includes the remote Paintrock Canyon Ranch in Wyoming that offers experiences for travelers of all stripes.