Mark Your Calendars: The Grand Tourist 2026 Guide to Art and Design Fairs

A great design or art fair sets the tone for the year, defines the conversations, and points to where taste is headed. These are the fairs defining 2026. Save the dates.

Welcome to The Curator, a newsletter companion to The Grand Tourist with Dan Rubinstein podcast. Sign up to get added to the list. Have news to share? Reach us at hello@thegrandtourist.net.

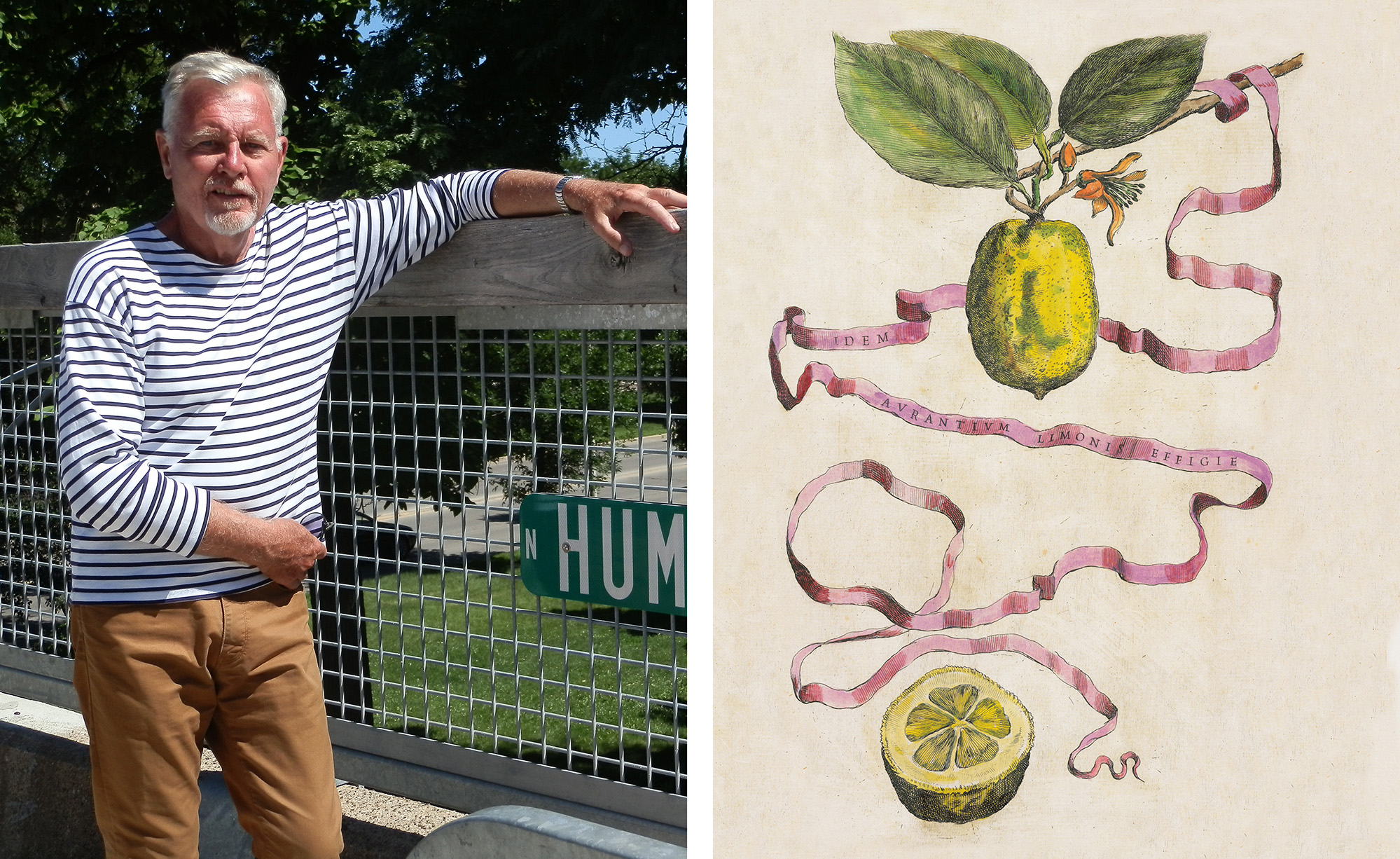

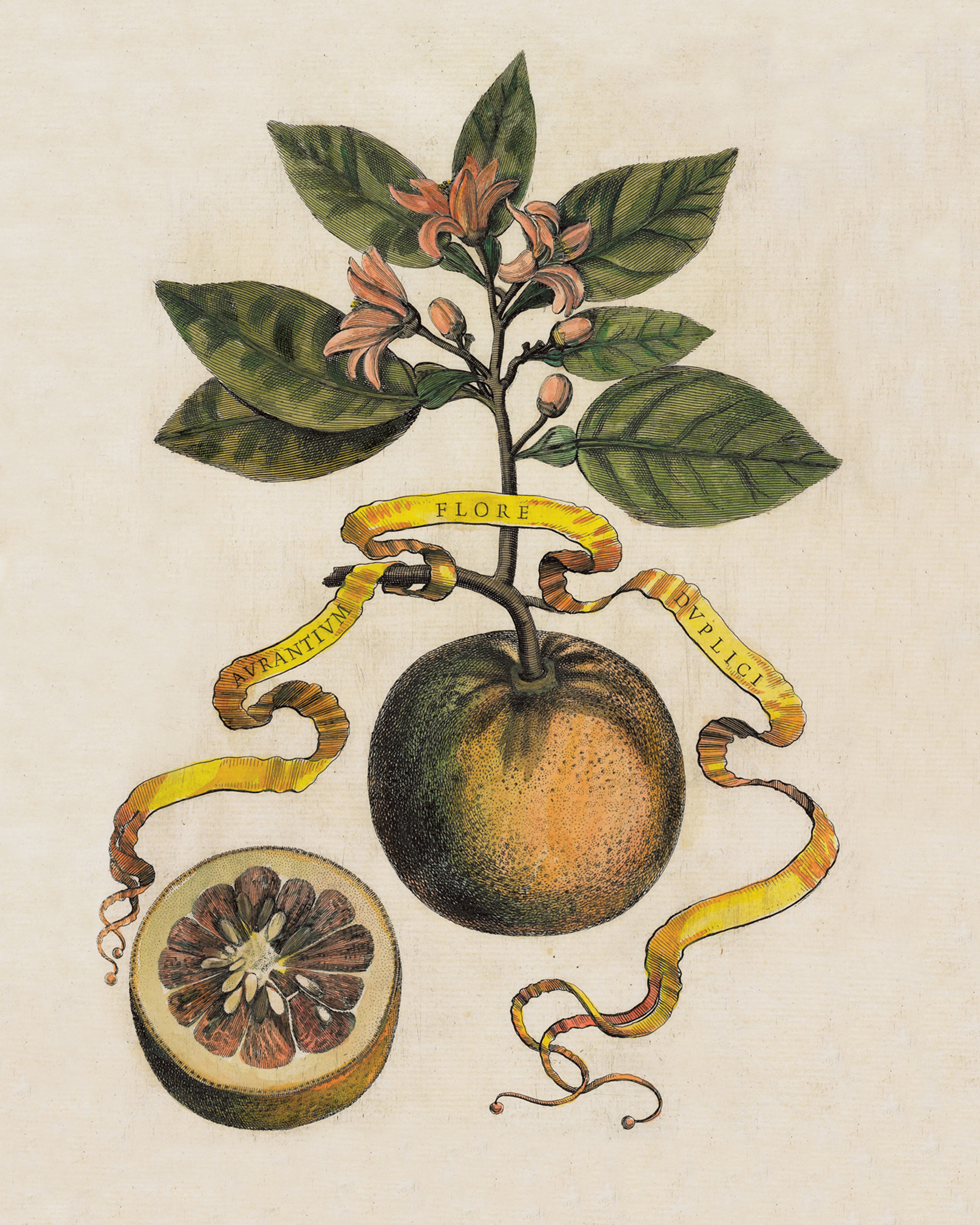

Ever since the landmark 1995 book “How the Irish Saved Civilization,” we seem to have an inexhaustible appetite for books that illustrate how sometimes it’s the less obvious people, places, and things that can be enormously influential in history. The new illustrated book “Citrus: A World History” (Thames & Hudson) is the latest example and a fascinating dive into the varied, fascinating, beautiful, and complex influence of the humble citrus. Written by botanist and writer David J. Mabberley, an emeritus fellow at Wadham College, University of Oxford, the book explores how Alexander the Great first brought the fruits to the West, the exploding importance of the crop during the age of seafaring trade and exploration, and the richly graphic traditions surrounding modern-day beverages made from the stuff. I asked David to help me dive into this fascinating corner of history, both tart and sweet. —Dan Rubinstein

What inspired you to write this book? Why citrus?

It was all an accident! In the 1990s I worked on a project called “Flora of Australia,” an account of all known plants from Australia. Because I had spent many years studying the mahogany family, from tropical Asia to New Guinea, I was apparently the one to deal with those. But the publication was stalled because no one had prepared a survey of the Australian trees from the related citrus family, to appear in the same volume. So I volunteered to take that group on to accelerate things, not realizing it would lead to a deep interest in the group, culminating in “Citrus: A World History.” The first—and as it turns out, fundamental—thing I had to tackle was that my work showed that the Australian trees were misclassified, bearing non-citrus names, so not reflecting their true affinity. I therefore moved them into citrus, showing that Australia has more native species of citrus than does any other country. This was confirmed by later DNA work, and it leads to a possible solution of the crisis now facing the citrus industry.

There’s a wonderful section of the book that details ancient references to citrus in everything from Arabic maps to Jewish burial plaques to the Far East. What’s the earliest reference you have found to citrus in history?

This is a difficult one because dating some records is not straightforward, and many of the datable ones probably include information from earlier, now lost ones. Although citrus was no doubt long used by indigenous people across the range of native citrus trees—Australasia north to China, southern Japan, and northeastern India—the domestication and hybridization of native species to give the hybrid crops making up the modern citrus industry was in China. There is no such thing as an orange, lemon, or lime growing naturally in the wild in China or anywhere else. The earliest datable records from there are from around 1300 BCE in the oldest Chinese geographical book known, though it refers to events 900 years before that; however, it was not published until the fourth century BCE, and that is antedated by Indian accounts from before 800 BCE.

The cultivation of these fruits must have changed over time. Would we recognize a lemon or other citrus from 500 years ago? Would they taste the same?

Yes, they would. Although many new kinds of citrus have been developed and continue to be developed, many of those depicted in Renaissance paintings can be recognized as cultivars growing today. They not only look the same, but would taste the same. This is because they produce seeds that exactly reproduce the mother plant and are not the result of pollination between different strains. This means that much of the modern citrus industry is based on genetically identical individuals, which lays the crop open to catastrophe in terms of disease—as is indeed happening in the U.S. today because of the introduction of huanglongbing, or citrus greening. It’s a bacterial disease spread by insects, which is already leading to colossal losses in Florida, for example.

The connection to vitamin C also plays a role in history. What might people not understand about this part of our past?

Unlike most animals, we cannot synthesize vitamin C because we have a malformed enzyme produced in the liver, suggesting that our ancestors were fruit eaters, so that this defect was not disadvantageous in evolution. Although citrus has reasonably high levels of vitamin C, other fruits, like peaches with twice as much, have higher levels. The importance of citrus is that unlike most others, the fruits remain fresh for long periods and so could be taken on long voyages without spoiling. This was to lead to the reduction of the devastating disease scurvy at sea. Use of lime and lemon juice by the British navy led to its sailors being called limeys by Americans, a name since extended to British people in general. It gave the British a strategic advantage over the French at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, for example, but it was only in the 20th century that the concept of vitamins was elaborated. And only in 1933 was vitamin C artificially synthesized, from glucose. The importance of vitamin C was to be overplayed, and the legacy of the great American scientist Linus Pauling was sullied by his advocating vitamin C megadoses for cardiovascular disease and even to cure late-stage cancer, for which there is no hard scientific evidence whatsoever.

Out of all the stories about citrus in the book, is there one point in history you’d like to personally go back in time to visit?

The Medici in Renaissance Italy amassed huge collections of all the citrus known in their time, and they had them illustrated in magnificent paintings: To have been in their gardens and palaces at that time would have been citrus heaven.

Did anything surprise you when doing the research for this book?

Very many things. To start, the fact that Casanova used lemon juice as a contraceptive! Perhaps the most pervasive is the fact that the Dutch House of Orange, and its adoption of the color and thereafter Dutch patriotic fervor for citrus-growing, is based on a pun. The origin of the house is a city in France called Orange, which has nothing to do with either the fruit or the color named after it. This flows on of course to the flags of New York and Albany, the Orange Free State (now South Africa), and the Orange Order in Ireland. Also, the origin of the Mafia can be traced to protection rackets involving citrus growers in 19th-century Sicily.

As the expert, what’s your favorite way to enjoy citrus fruit? Are you a fan of orange juice in the morning?

Perversely, perhaps, I am not a fan of eating oranges or even drinking orange juice, which may eventually begin to disappear from our diet anyway. But I enjoy marmalade prepared by my partner, including that made from our native Australian finger limes grown in our rooftop garden in Sydney. And I love a decent Key lime pie when in Florida, and I will not, of course, pass up a glass of limoncello, curaçao, Cointreau, Grand Marnier, or Campari. They’re all citrus products!

An Extraordinary Empire Remembered; a New Side of Henry Taylor; and Other Shows Not to Miss

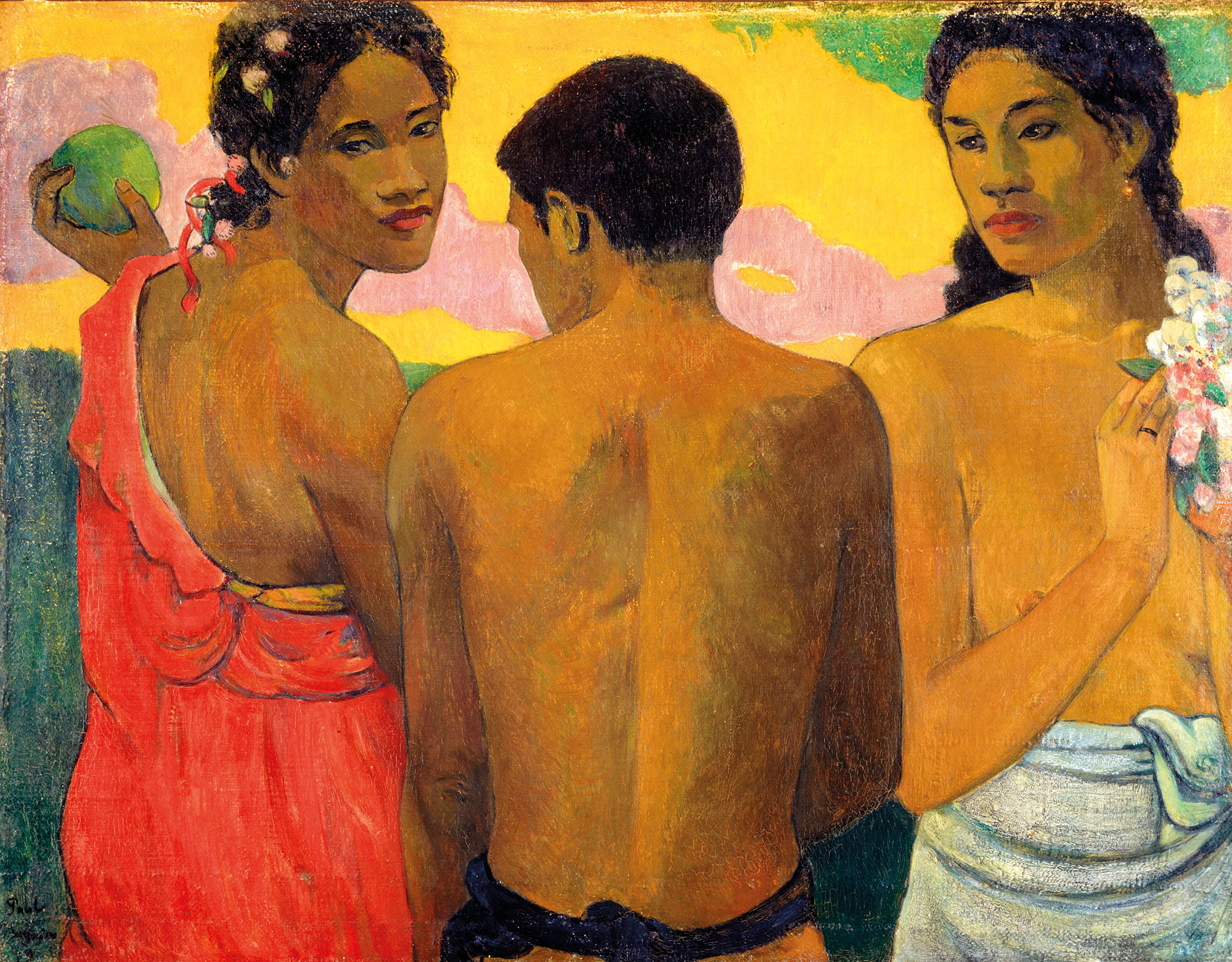

Houston, “Gauguin in the World” (Until Feb. 16)

Born in 1848 during revolutionary tumult in Paris, Paul Gauguin’s life was marked by sociopolitical upheaval. Following the revolutions, the family left the city for Peru in 1851. Gauguin’s father died on the voyage there. Later, the family returned to France, where Gauguin entered the French navy, spending six years at sea before settling down as a stockbroker. Following the financially ruinous collapse of the French stock market in 1882, he began to paint. But he didn’t achieve much recognition in his lifetime. It was only after his death that the largely self-taught painter garnered attention for his unprecedented use of evocative color and form that would influence Picasso and Matisse. With 150 paintings, sculptures, prints, and writings, this exhibition examines his prodigious life and work. mfah.org

London, “Ash Roberts & John Zabawa: Of Merit” (Until Nov. 10)

Born in L.A. to a family of landscape designers, artist Ash Roberts learned early on to appreciate a landscape’s careful composition. As a painter, she preserves that beauty in serene renderings of lily pads and horizons. At this show, the emerging painter makes her international debut alongside fellow L.A.–based painter John Zabawa. His series of melancholic still lifes complete the presentation’s simple beauty. francisgallery.com

London, “The Great Mughals: Art, Architecture and Opulence” (Opens Nov. 9)

From 1526 to 1660, the Mughal dynasty, one of the world’s wealthiest empires, reigned over a large swath of South Asia. The empire’s exceptional artistic output was the culmination of Hindu, Iranian, and European influences. This is the first exhibition to examine the Mughals’ creations, from bedazzled daggers and mother-of-pearl wine cups to intricate carpets, most of which have never before been exhibited. Some of the only surviving paintings from the Book of Hamza—originally 14 volumes filled with the popular stories of the Hindu hero and decorated with 100 ornate paintings—will be on display. vam.ac.uk

New York, “A Billion Dollar Dream: The 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair on its 60th Anniversary” (Until July 13)

The 1964 New York World’s Fair promised to be a “magnificent spectacle, significant marketplace.” Surrounding a huge steel globe sculpture in Flushing Meadows, Queens, 80 countries and nearly 350 American companies came together to present exhibitions, activities, performances, films, and art. The fair advertised an American utopia, showcasing the latest marvels like the new Ford Mustang. But it also received attention for the fraught financial difficulties of such an ambitious endeavor. On the fair’s 60th anniversary, this exhibition examines its environmental, social, and political consequences through archival photographs, documents, postcards, and other archival ephemera. queensmuseum.org

New York, “Henry Taylor: No Title” (Until Feb. 15)

Last year, American painter Henry Taylor was the subject of an unforgettable retrospective at the Whitney Museum. He’s painted obsessively for more than 30 years, portraying most everyone—friends, family, strangers, even patients when he worked at a hospital—in raw, candid portraits. In this show, Taylor forgets acrylics and dabbles in printmaking, a well-suited medium for experimenting with his trademark striking color palettes. Still lifes, portraits, and etchings inspired by earlier paintings reveal a different side of Taylor’s artistic practice. hauserwirth.com —Vasilisa Ioukhnovets

A great design or art fair sets the tone for the year, defines the conversations, and points to where taste is headed. These are the fairs defining 2026. Save the dates.

We assembled our favorite design objects for the people on your list that have everything, including taste.

We checked in with our former podcast guests who will be inching through Miami traffic, unveiling new works, signing books and revealing new projects this year.