Mark Your Calendars: The Grand Tourist 2026 Guide to Art and Design Fairs

A great design or art fair sets the tone for the year, defines the conversations, and points to where taste is headed. These are the fairs defining 2026. Save the dates.

It’s hard to think of a famous person from the past half century that hasn’t sat for a portrait by Jonathan Becker. From Madonna and Mikhail Gorbachev to Gore Vidal and Andy Warhol, this legendary photographer’s work is exposed in a stunning (and first) monograph, Jonathan Becker: Lost Time. On this episode, Dan speaks with Becker about his days as a young protégé of Brassaï, his days in New York during the heyday of the ’70s, his decades of contributions to Vanity Fair, his thoughts on the art form today, and how he once drove Diana Vreeland around in a taxi.

TRANSCRIPT

Jonathan Becker: Brassaï told me, never give a picture to them [subjects] for 10 years. But there’s reason to it. First of all, they like the picture better, they’re much more likely to like the picture in 10 years. Well, also, you don’t really know right away what is the good picture. And I felt on assignments that I really didn’t get it somehow or something was wrong. And then I’ll come back and I think, what are you talking about? This is great. And then sometimes right away I’ll look at something and think it’s wonderful—and it’s nothing.

Dan Rubinstein: Hi, I’m Dan Rubinstein, and this is The Grand Tourist. I’ve been a design journalist for more than 20 years, and this is my personalized guided tour for the worlds of fashion, art, architecture, food, and travel, all the elements of a well-lived life. One of the great things about doing The Grand Tourist is getting to meet, even if for only an hour or two, some of the most fascinating figures in the world. Each encounter leaves a story behind. And the podcast is a kind of portrait in MP3 format. The more people I get to meet, the more fulfilling it becomes, like collecting signatures in a book with endless pages. So if you judge someone’s wealth by the incredible counters they’ve had in their creative career, my next guest is probably the richest guy you’ll ever meet. Jonathan Becker, born in 1954 and raised in New York, Becker was one of those kids with talent and guts and found himself at the right place at the right time.

As a young man, he traveled to Paris to become the protege of famed photographer and artist Brassaï. And when he returned home, he found himself unwittingly at the center of a Cultural Revolution in 1970s New York. Later on, he found himself shooting for the likes of Interview Magazine, Women’s Wear Daily, Vogue, and of course, Vanity Fair, where he was called upon to shoot society’s creme de la creme for decade after decade. His enigmatic photographs have now been collected in his first true monograph from Phaidon called Jonathan Becker: Lost Time.

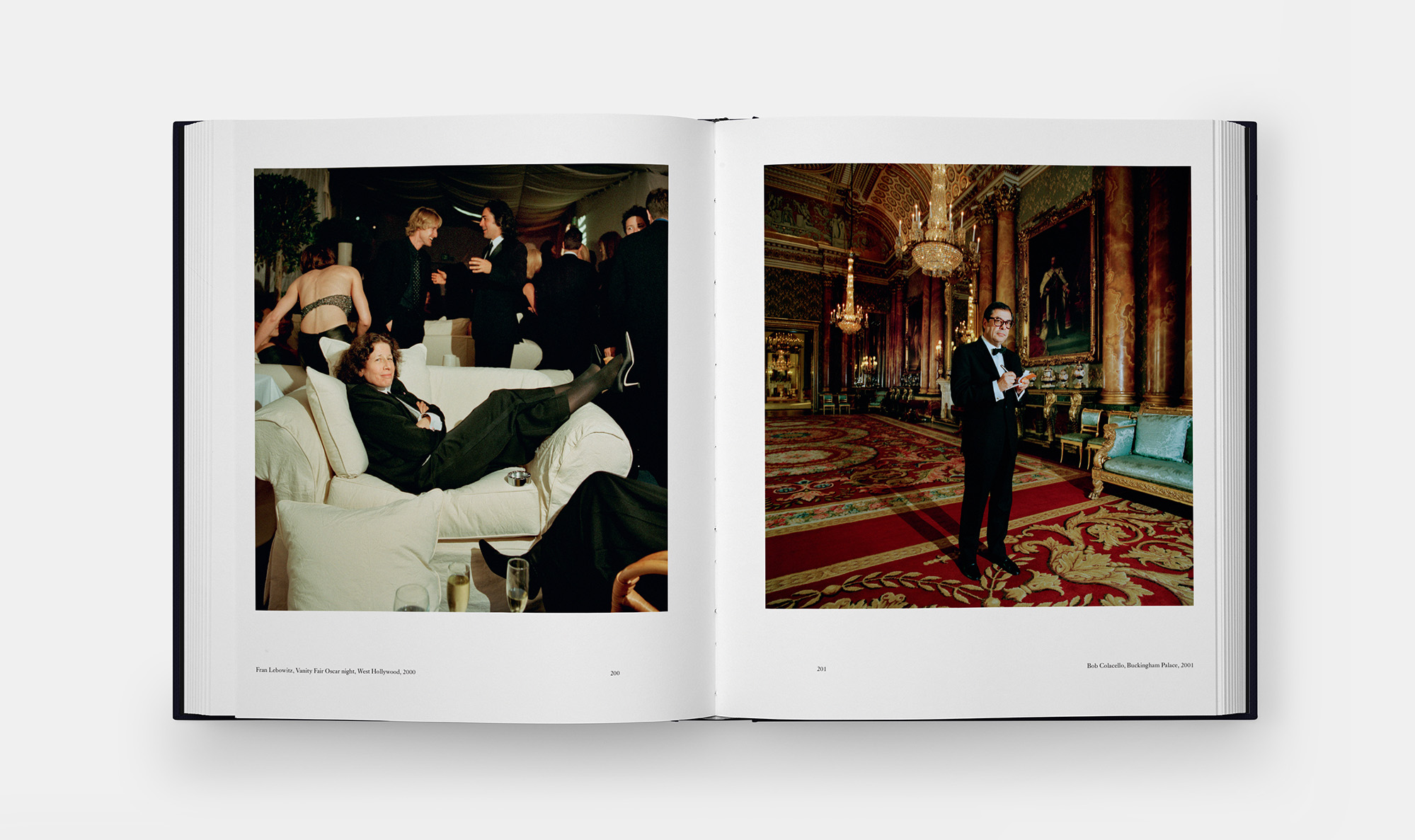

Page after page, you’ll see both in black and white and color, soul-snatching shots of everyone from Donald Trump and Mikhail Gorbachev to Madonna, Andy Warhol, Prince Charles, François Truffaut, Billy Wilder, Fran Lebowitz, and Jacky O. All shot in a square format thanks to his trusty Rolleiflex camera. I caught up with Jonathan Becker from his house in the country to chat about how he met Brassaï, working for editorial legends like Bob Colacello, what it was like in the early days of the Vanity Fair relaunch, why he thinks the art form of photography is basically over, and the time he gave Diana Vreeland a ride in his taxi.

I wanted to start at the beginning with you, and I read that you were born in New York, but I don’t know too much about your early life. So were you raised in the city?

Yeah, I was born in the city. I think I was… apparently, I was conceived in Allen Ginsberg’s Loft—

Really? Okay. How’d that happen?

Because my father was all involved with… His great friend was a fellow named Lucien Carr who was the kind of epicenter of the beatnik world from St. Louis. They were both from St. Louis. My parents moved uptown quickly to a railroad flat, which is where I was brought from the hospital.

Oh, okay. And did you spend your youth kind of growing up on the east side?

Yes. The railroad flat lasted a year or so as they were both career people in a sense in the arts. My father, he was a drama critic at the time, but he moved quickly and went to work with a fellow named Roger Stevens, who was a big real estate magnate and produced Broadway shows.

And what did your mom do?

And she was at the time, a Martha Graham dancer.

Oh, I see, okay.

She was kind of the protege of Martha Graham, who was my godmother.

Oh, I see.

So that answers your question about the arts.

Yeah.

So with Roger Stevens, it was… I mean, they produced West Side Story. They had all kinds of endeavors… They bought and sold the Empire State Building. My father was the protege of Roger Stevens who was called to be Kennedy’s advisor to the arts in 1961 or so, I think. He lent my father some money with which he bought Playbill… built it up with editorial content. He hired Leo Lerman. Do you remember him? He was the editor at Vanity Fair for a little while. He was Vogue’s Arts Editor for decades, but earliest. he did this with Playbill… My father was a big Harvard man, Rhodes Scholar, doctorate at Oxford forever disappointed in me because I didn’t go to college. And he bought Janus Films with the proceeds from Playbill, and he built that up. So he was a film distributor, and my mother went on to become a choreographer. And as they succeeded in their respective careers, we ended up in a proper apartment on 72nd Street.

And did you take pictures as a kid? Do you remember—

I did. There’s a picture of me and my sister running through Central Park behind the then much smaller Metropolitan museum. And I had a brownie around my neck. I guess I was… It was fated somehow, something I could do.

And did you enjoy it? I mean, as a kid, did you think this is what I want to do with my life, or was this just something that you did for fun or?

Well, it always seemed magical, the idea of being able to review something that happened. But it’s a form of documentation before it’s an art form. And in a sense, the more organized you are with it, the more magical it becomes. And there’s a science to it. It wasn’t until I began to use my own camera and keep the negatives and get them organized and have a dark room, which eventually I did. It always had a link to work and a livelihood for me. When I had to get summer jobs very early on and I was a busboy in a sloppy Irish restaurant—everyone went there. But I saw what went on in the kitchen.

I couldn’t believe it—it was awful. The manager of the restaurant was cruel. And so I thought, well… I started to take pictures out in Long Island. I started to take pictures of children for their parents. Those were my first portraits. And then I built a dark room in the attic and it worked. So I always knew… I always felt I could make this work somehow from a young age. I never really thought about doing anything else.

And at a certain point, you found yourself in Paris. And how did that happen?

After secondary school, I didn’t know… I really did not want to go to college because my father was teutonic and overbearing, full of himself. And although I loved him, and he was kind of a wunderkind, I didn’t want to stay in his arena. His mother [my grandmother] had died and left me a Volkswagen, a little bug, and I fled. I drove out west to Colorado. I got as far as Colorado, and realized that I had no means of… I turned around and went back to Harvard Summer School because anything that had ‘Harvard’ in it was okay and blessed, and it gave my father some hope.

But I mean, it was a random idea. And I picked randomly three courses that intrigued me. The one that most intrigued me was a postgraduate course on Surrealism. It was taught in French, for which I had grammar school French. I have a very good grammar school education. That’s it. So the professor accepted me for some reason. Come the fall, I still didn’t know what to do with myself. So I told my father I had to write a thesis for the course. And I remembered he had spent years writing his doctoral thesis. I thought, well, that’ll buy me some time. I went out to Long Island where we had a house—where my mother still is, and I spent the fall writing about Brassaï whose work intrigued me to no end. And who was not a surrealist and hadn’t been part of the course. And I wrote it in English and didn’t send it in until February.

And I got a letter back from the professor who said that it was very late. And that since the piece was written in English [not the required French], I flunked. And he made all kinds of comments in red. And then he said… Well, it just so happened that he was an acquaintance of Brassaï’s and he recommended that I send the paper to Brassaï. And so I did. And then Brassaï wrote me a letter back that said—that April, I got it—It said that the paper had given him—in French, he wrote—a great satisfaction. And that I had “understood and expressed the spirit in which he photographed”. And I thought, this is… I mean, I can die now. I’ve done something. And even my father was impressed and he found me a room in Paris, a maids’ room recently vacated by Jean-Pierre Léaud, Truffaut’s main actor and the kid [in The 400 Blows]. It [the room] was in Truffaut’s production house. It was a seventh floor walk-up. And I had it for a year. Actually, I could stay indefinitely. I think that was it. He’d done with me. He [my father] thought he was getting rid of me, that would be that. And then I had written Brassaï and said, “I just happened to be coming to Paris.” And we had lunch and the rapport grew over the 10 remaining years of his life. And we got very close. He had no children, and I helped him and he helped me. His stock was kind of low at the time. He’d had a big show at MoMA in New York [in 1968]. And since then he hadn’t been able to publish books on photography. He was writing biographies of his friend Henry Miller. He did a big one on Picasso called Conversations with Picasso. They were great pals.

And he had written a book on Proust and Photography. He was obsessed with Proust. And Brassaï had these pictures in New York. He had 200 beautiful prints that lingered in New York with a literary agent who was not getting them published—they were the sort of naughtier pictures from his Paris by Night period, which was 19, sort of 29 to 32. And they were in bordellos, in opium dens and some nudes and all kinds of goodies that he couldn’t publish in the ’30s.

So I was getting homesick in Paris in this walk-up maids room, and I wanted to go home at Christmas. I wrote my great friend Elaine at the restaurant saying that I wouldn’t be coming home for Christmas. She got the message and she sent me a Christmas card, and in it were three crisp hundred dollars bills. She used to keep big wads of cash in her brassiere—she was ample in all kinds of ways. And she said, “Take Icelandic. There’s a dollar left for cigarettes.” And so I did. And Brassaï said, “Would you go get these prints for me?” Those 200 prints, I mean priceless things. But I went down, I was 20 years old. I went down and got the prints from the… Recuperated them from the literary agent. Took them up to Elaine’s. Everyone poured over them, not drinks, eyes. I mean, it was like they were finding some sort of a holy grail. The writers that frequented Elaine’s and it was principally writers [that frequented Elaine’s] were all enamored of Hemingway. And the Paris between the wars and this stuff was an unseen trove. And George Plimpton was there, the Paris Review founder and… Oh, I can’t remember all kinds of people. Elaine too. Then I got them [the prints] back to Paris safely, and they became a book called The Secret Paris of the 30’s. And so he was very happy with me to do that, that I had done that for him. Was able to do it. Brassaï was happy.

And what would you say you learned from him as sort of like a protege? Now in retrospect, what do you feel like he imparted to you?

It’s very hard to articulate that because he was not taking photographs anymore. When he looked at… He did not elaborate on his work more than what he’d written. I learned more from his writing than I learned directly from him about photography. When he commented on my own work, the phrasing was very simple. He’d just say… He’d either say nothing or he would say, “C’est bon,” and that was it. It’s good or nothing. That’s all. And that simple. I always like to keep things simple. So… And he didn’t belabor anything. What I learned was from my osmosis, the way he managed his life and which was exceedingly eccentric. I mean, money was never a concern for him because… I mean he had a dearth of it. But he’d make money selling something… [money] from a book or from magazines or selling a print or something. And he would stick the cash in a [random] book [in his bookshelf] and forget which book it was. He had an odd relation with money, which probably hurt me in some ways.

Because he didn’t pay you?

No, no. We didn’t have a transactional relation in any way. He never paid. He gave me prints and things, but I wasn’t supposed to be working for him. I worked for a fashion photographer in Paris. Tony Kent was a big deal at the time. Jill Krementz’s brother, he’d taken the Kent out of Krementz, K-E-N-T, and he was photographing the Beatles and all the big models, and I tried to… I was recommended to him, and I tried… I broke his camera on the first day. It didn’t work. No. I made a living in Paris playing backgammon at nightclubs and things like that. I got into the underworld in Paris. I was always intrigued. And there was a parallel with Brassaï because he photographed so much of the underworld 50 years earlier

(SPONSOR BREAK)

And at a certain point, you come back to New York and you start shooting for magazines like Town & Country and Interview.

That was later. No Interview was earlier. I got to Interview through Brigid Berlin. She was also known as Brigid Polk. She was Andy’s right hand, and she was best friends of friends when I had a dark room in Christopher Cerf’s basement in 1973. He was a son of a Random House founder, Bennett Cerf, and I ended up keeping that dark room for 47 years. He was a great benefactor, but his wife was great friends with Brigid. And so that was my introduction. And Brigid introduced me to Bob Colacello. So I had my first real magazine assignment in 1974, I think early ’74 for Interview. And then when I got to Paris, I was hired by the W, brand new magazine was W. It was a big broadsheet color version of Women’s Wear Daily.

I remember it.

I was recommended to it—to the editor, and I didn’t really understand anything about fashion. I thought it sounded like ladies’ underwear, Women’s Wear Daily. I didn’t know what it was. I thought it must be some sordid thing. And I told him I wouldn’t work under my real name. I had to use a pseudonym. So I took my middle name. He [the Editor] was furious, but I did covers and all kinds of things. I became the first Paris-based photographer for W. He fired me eventually. He couldn’t stand me. But I did a good portrait of Louis Malle. I did other actresses and so forth, never any fashion. And that portrait of Louis Malle ended up running in the prototype of Vanity Fair.

Louis Malle, who, people who listen to the podcast might know his nephew was a Frederick Malle, the perfumer.

Yes, that’s right.

He was also on the podcast and mentioned Louis Malle to me. We talked about that for a little bit.

Oh, you had… Oh.

Yeah, so Frederick was—

He’s a pal. He’s a great guy.

Oh, well tell him I say hello. That’s another thing in common. And so what was it like shooting for Interview back in the heyday? Did you actually interact with Andy on assignments as well, or just with his team, or how was that back then?

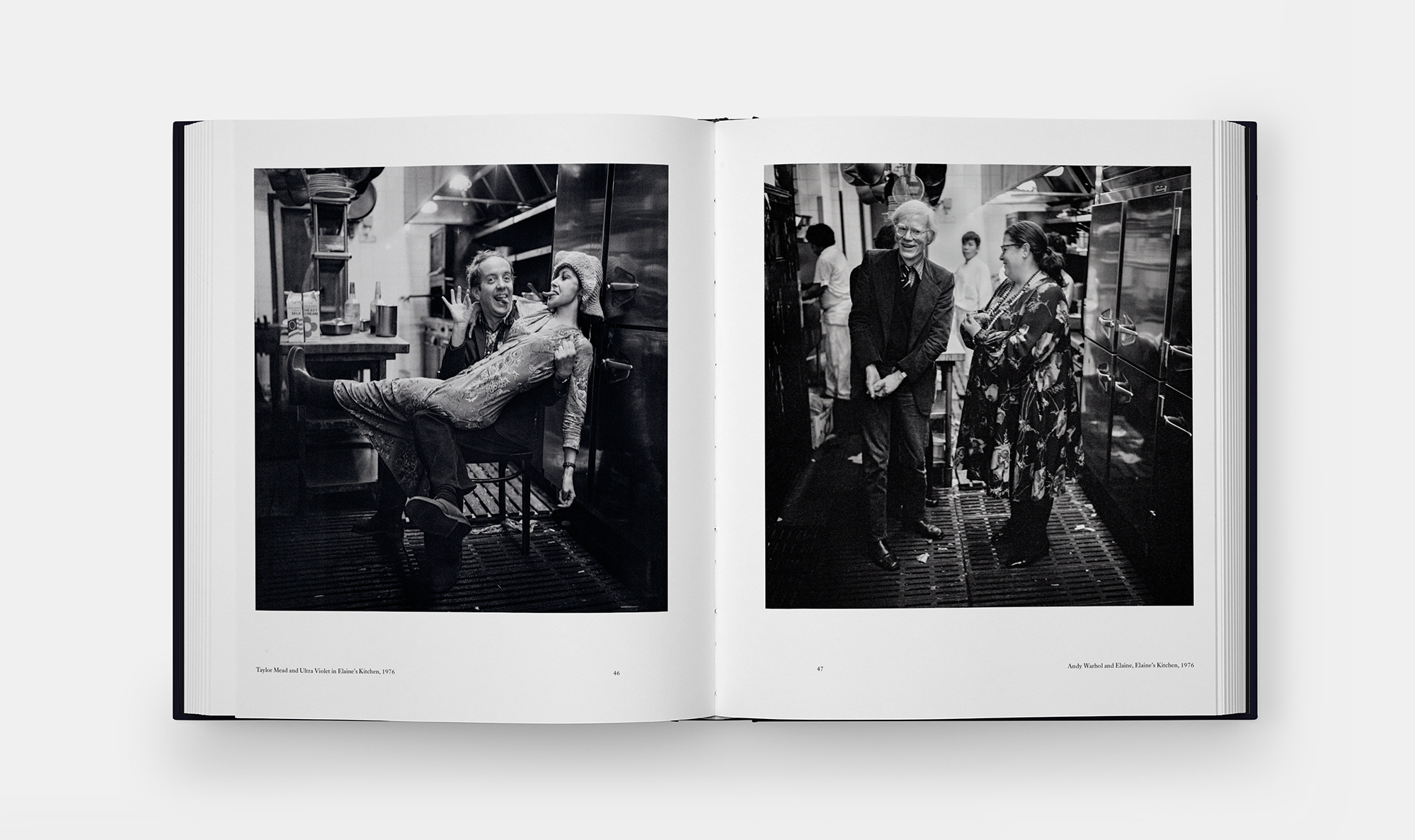

Well, I didn’t see Andy have much to do with Interview. Bob Colacello was the editor. They had very good art direction. And it was, anything goes. It was wonderful. Bob is a great editor. It’s tremendously in innovative and spontaneous and inspiring. So I would bring things that I wanted to do. And this was when I got back from Paris and I had started to do portraits of people in Elaine’s Kitchen at the restaurant. There was fluorescent, there was light in there, fluorescent light. I hadn’t-

Good lighting.

Well, it works. It was barely enough for Tri-X film. But it was perfect. It was vaguely soft and there was always stuff going on in the kitchen. And the kitchen help enjoyed the diversion, and people enjoyed the diversion of being asked to come into the kitchen.

I remember seeing, there’s some photos of the cast of SNL, the Saturday Night Live [inaudible 00:22:31].

Yeah. Oh, I did dozens of people at Elaine’s. Everybody was going there then. And because I was “the kid” and she let me do just about anything that didn’t piss people off. And I knew them, the Saturday Night Live group through a fellow named John Head, who was an early friend of Lorne’s at the invention of Saturday Night Live. He was a writer.

It’s not formal. It’s easy. It’s a moment… and everybody’s game. It was a game time in the seventies. People just did things on a whim. And I caught it well. I caught that wave of whimsy and I don’t know, I must’ve done 30 portraits in the kitchen at odd times, and I wanted to make a book of it. Elaine didn’t like the idea at all. She didn’t like anything that might alter the chemistry of what she saw as her success. And so she gave me a bill. I used to stay with her there until sometimes [closing]—I’d drive her home in the Volkswagen and lock the place up, pull the gates down and everything, and we’d eat a lot of spaghetti and I’d play backgammon and so forth.

For what?

And she sent me a bill for $500 for all this spaghetti. And it was her way of saying, “Get lost.” She knew I had no means. So I got back in the Volkswagen and drove to California. But Bob [Colacello] published half a dozen of those portraits in Interview. That was the first place they were published. It wasn’t it a book, but I got a spread in Interview. And then he published—later on – an interview I did with Brassaï when he came to New York. Important things. He was cranky at the time. Bob was very cranky, difficult. He had a lot of pressure dealing with Andy and not much time for the perfunctory relationship we had at the time. We got much closer later at Vanity Fair.

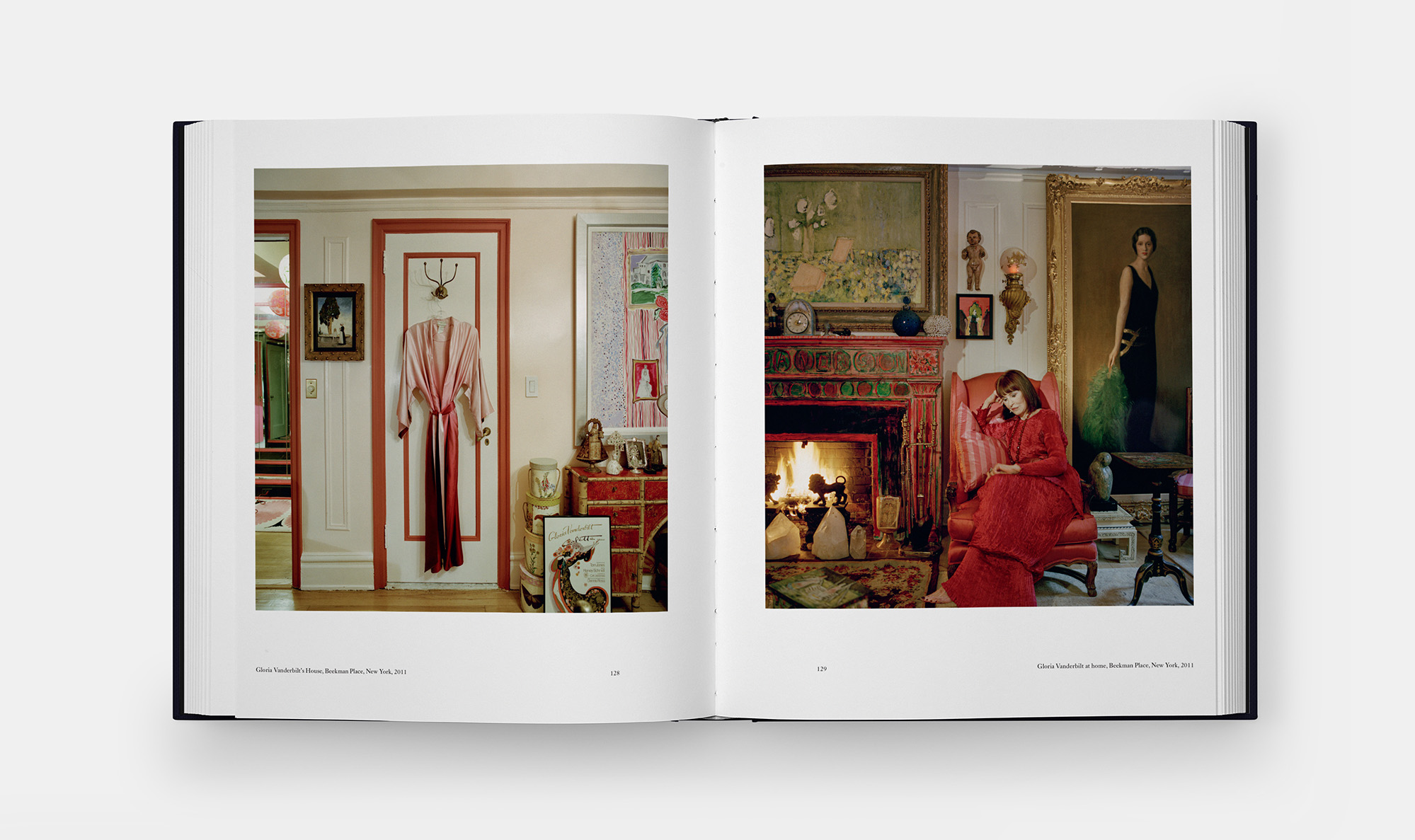

And there’s a lovely portrait of Diana Vreeland that you shot in 1981 that’s sort of labeled just at your exhibition of the, we know much about the photograph. She looks like she’s looking over maybe some slides or like a tear sheet or something.

Well, I had photographed her. When I got back from Paris, well, I had to flee again with the $500 bill I got back in the Volkswagen. I went to California for three dark years before I came back to New York in 1979. I enjoyed California too much, but I was terrified of becoming a Californian. And I thought if I stayed there too long, I better get back to New York. I came back and started to drive a taxi, and it was my first real job outside of photography. And the only one I’ve ever had. I did other things in California. I moved boxes. I worked for sordid magazines, unmentionable things, but there was always photography. And then I got into touch with W Magazine, Women’s Wear in New York. And it turned out that John Fairchild [the owner and publisher] had liked the work I’d done in Paris and regretted that I’d been fired there. And they hired me. And one of the first assignments was Diana Vreeland.

Wow. Okay.

Whom I didn’t know. I knew her family. I knew her grandchildren. And Nicky I was very close to, he’s a monk now, Buddhist. And he still takes pictures. Great friend. I knew his father, Frecky. I knew I’d met the uncle, Timmy in California, who’s an architect. And I was driving down Second Avenue in my Checker and I was on my way to have dinner somewhere. I wasn’t a very good taxi driver. I didn’t hustle. I liked to stop. I spent almost all the money I made every night on dinners and things.

And lo and behold, there’s Diana Vreeland hailing a cab outside the Beekman Theater, the movie theater, beautiful movie theater. And she gets in my Checker and I talk to her. I introduced myself to her and talked all about her family, talked her ear off, and then dropped her at home. And lo and behold, a number of months later, I had this assignment to photograph her—

Oh, gosh.

From W. With André Leon Talley. That’s where we really connected. And he was a great friend. And so when I had my exhibition down in Chelsea, my first exhibition, she [Vreeland] came on her own day. She made a special appointment to meet me down there. She loved the portraits I’d done of her. And that’s what she was looking at in that photograph.

What was she like as a person?

Oh, just what people imagined. She was enthusiastic, decisive, surprising, unique and original and of extraordinary taste. I mean, just when I met her, I knocked on her door and I reminded her that I was the taxi driver.

Did she remember you?

Yeah, of course. Oh, the other figure, the other weird coincidence was that the movie she’d seen [at The Beekman Theatre] was “L’Innocente,” a Visconti movie, which had in it Marc Porel, my friend from Paris. He was one of the actors, he played a poet and he had this great full-frontal nudity scene in it. And I reminded her, I told her that he and Jennifer O’Neill was the other… She was one of the stars of “L’Innocente.” And she and Marc ended up shacked up in Bedford, New York where I had visited them. I’d stayed up there for a week with them and so, I had told her I knew the actor and the this and that, and so she remembered me, for sure. And she said, “Oh, I just love people who work.”

I think, in her in line of work, she met a lot of people who didn’t.

She met both kinds of people. She worked. That woman worked hard, she really did. She created the Costume Institute [Metropolitan Museum] and she was resilient and she came up from the ashes. I admired her to no end.

And then, in ’83, you were involved with the relaunch of Vanity Fair, which was—

A little before that.

Oh, really?

I was still driving a taxi. When I came back from Paris, Gilles Bensimon, the fashion photographer, gave me an introduction to Jean-Paul Goude in New York, who was then the art editor of Esquire and doing these wonderful illustrations for the covers of Esquire and so forth. And he was working on his Jungle Fever book. I think he was living with Toukie Smith, and then later he was living with Grace Jones and fomenting her career.

Jean-Paul was a real hero to me, but Jean-Paul sent me to meet Bea Feitler who was a great, great art director and very young, beautiful, Brazilian. And she had come up from Brazil in the ’60s and gone to work for Brodovich at Harper’s Bazaar, [and with] Marvin Israel. And she was a partner of Ruth Ansel. And she just did unbelievably great and original work. And she fomented the careers of Diane Arbus, she worked with Avedon, she did Helmut Newton’s first book, White Women. Annie Leibovitz, she was really fundamental in helping her become a portrait photographer. And she lit on me. She loved my Elaine’s Kitchen, and she’s the one who really got me working because I didn’t know how to make a career. And she guided me.

I met Bea when I right got back from Paris, and she’s one of the reasons I came back from California because she was trying to find me. [She called my parents.] Where did he go? And I worked with her at Rolling Stone, and then she was called by Alex Liberman to do the prototype of Vanity Fair in 1981. And I introduced her to Nicky Vreeland, who became the photography editor. She did most of everything and she put three of my photographs in this prototype launch, and everyone else in that prototype was very famous. There was Avedon, Penn, Helmut, Annie, Bill King, who was a big fashion photographer, Dominique Nabokov, who was very well seen—and me. Bea used my portrait of Louis Malle, a portrait I did of Brassaï. And she ran a beautiful layout of Brassaï’s portraits of artists. Picasso, Matisse, whatnot. Giacometti, I think. I can’t remember the three that she used. And then she used the artist’s work opposite. Beautiful layouts. She sent that to the printers and then she went back to Brazil and died of cancer within two weeks. And it was a big heartbreak in my life.

That’s terrible. And, with Vanity Fair, how did that evolve? Because it was kind of a success, or back then, I’m not familiar with those early days of Vanity Fair in the ’80s.

That was the prototype. It came out in ’82, and then the first issue came out in ’83. The prototype had no writing in it. It was all dummy text from Thackeray’s Vanity Fair. The first issues were bumpy, and then they got a new editor, Leo Lerman came in. I loved him. He was just great to work for. And I stayed working there. It was really thanks to Si Newhouse’s determination. He kept at it. He’d wanted to buy The New Yorker and the Fleischmann family wouldn’t sell. And so, this was his idea to extract Vanity Fair back out of Vogue. It had been incorporated in Vogue when it folded in the ’30s, and then Tina came, quickly, and it was really spoken about and it had “buzz”, in Tina’s words, and it was another place where you could do your own work. I was very lucky because I never did anything that was more than all I really knew how to do, which was portraits. And no one ever told me what to do.

They never told you, “This is the look we’re going for?”

No.

It was always just, “Hey, go do this. Go shoot this person,” basically?

I was given a subject matter and left to my devices. I think what I did was useful to the magazine. It’s also possible that people tried to tell me what to do and I didn’t listen.

Also possible. Only you would know. And shooting parties and events and things like that was also a part of things. Were those your first—

For W, in New York, they started having me do that. I was still driving a taxi. I drove a taxi from ’78 to ’81, at night. They’d say, go photograph some event, and it was in someone’s house or in something. And I just parked the cab and then go in and photograph. I had a little Rollei camera, a little 35 millimeter with a little flash on it. And I just found it very easy to do. And I don’t know why, but it was very fluid. I’d go up, take some pictures of people, get everybody with this little camera and get back in the cab and keep going. And it worked.

And because I was at ease doing it, later on, I didn’t really enjoy this fully because it wasn’t productive of very interesting pictures. Later I figured out how to extract really interesting photographs from events. And the first place it happened, really, was at Vanity Fair… Leo sent me up—Lloyd Ziff was the art director—to the American Academy of Arts and Letters, their annual awards, and the people there were the highest names in the arts, and painters, principally writers. And it was like ducks in a barrel. And I decided not to take a 35 millimeter, to use my twin lens Rolleiflex, which was really my staple, always. Square format. It’s a camera that, really, you don’t change lenses. It is what it is. It sees as close to what the human eye sees as any other, more than any other camera ever did. That was the object of developing that lens—particularly the 75 millimeter version of it—in Germany. And it was like magic to me. And I was catching moments—

And for people that don’t know, that camera, if you’re thinking of the one that I’m thinking of, you look down on it, right? You’re not coming at it with your eye—

Oh, I love that. Absolutely.

That helped, probably, with party photography.

You look down into it, and people aren’t… It’s not an aggressive stance. And you’re looking into a… It’s also reversed. The picture’s reversed, so there’s some remove, and it’s almost like looking at your own little theater down there. It’s a whole different way of being in an environment because you’re not necessarily communicating with people. And I don’t know, something people always tell me, that they’re inspired subjects because I’m looking in and I’m amused with what I’m seeing, and I’m not aware of it. But it makes them happier too. I love that camera. I still use it.

And over the years, especially for Vanity Fair, you photographed a lot of important and famous people, people who are notable in different ways, politicians, actors, artists, writers, everybody that I could possibly imagine. Did you find shooting one or another required something different from you or was your approach to shooting an older novelist the same that it would be a young starlet or a politician or a woman of society? Did you approach them all the same on that shoot day?

I try to approach everything with no sense of prejudice, prejudgment. I do homework. I know more or less about each person, but I go in with pure curiosity. And so, everything’s different, in the sense that any relation with any person is unique and it’s really limited by time and the subject’s openness to… Because sometimes I have to figure out what I’m doing and I have to get to know people, and I don’t take pictures for a while, people think, “What’s he doing? He’s not taking any pictures.” And sometimes I have to go about just… I’ve even used no film in the camera just because, for a while, until I knew what I was doing, because at least they’ll talk more and I can extract things and figure it all out.

No, my approach is of curiosity and attention to the subject. And theater is important. What are they presenting? How are they acting? And perception can’t be a template. I wish I could do that. I wish I could do overlays. I wish I did have templates. It would make things much easier. A lot of photographers, Penn developed a template, Avedon had templates. Annie has templates, in a sense. But I’ve never been able to just go in and overlay a lighting circumstance and a background circumstance and all that. I’m too interested in the environment of the subject and how they relate to whatever’s going on around them.

And what would you say, if I had to ask you what is the Jonathan Becker secret to taking a great portrait, what would you say?

Oh, I have no…

It’s a tough question.

There isn’t one, I don’t think. If you want to take a portrait like me, you have to be me. I don’t know. Any photographer has their own perceptions, and I think that’s what comes through in a portrait. On the other hand, when I did Martha Graham, they wanted me to photograph Martha Graham for Vanity Fair—I’ll go off on a tangent—and she was my godmother. I thought this would be very easy. It wasn’t easy at all. I hadn’t spoken with her in years, and I called and called, and she never answered the phone. She had a minder who answered the phone and was keeping her from drinking. When she got older and couldn’t dance anymore, she drank. And finally she answered the phone and I said, “Where can we do this?” And she said, “I don’t know. They won’t let me do anything.” And she said, “Meet me backstage after the performance at City Center.” And she always did come on the stage while she was alive. After the performance, she always took a bow. And I get back there and there were tons of people everywhere, and there were all kinds of admirers. And they put me behind a rope and with a phalanx of photographers, and I couldn’t understand how this was ever going to come to anything. And she was sandwiched between Calvin Klein and Madonna and sitting there. And I was there with my Rollei and I had a flash, and she found me in this group. She was looking for me, I could see. And then when she found me, she locked eyes on me and my camera, and she posed like only Martha Graham can pose. And she didn’t stop.

So you couldn’t get an intimate… You couldn’t get anything candid from her, you felt like?

It couldn’t have been more intimate. It was as if everyone else disapperared, it was love. It was if there was no one else in the room. And they were all going about their business and they were all ancillary. And the picture was fabulous—I felt you can extract portraits in any circumstance, this is what I felt very good at. And so you had Madonna on one side and Calvin Klein on the other, but it’s not their portrait, people are intrigued with that, but it adds to the picture. It’s a portrait of Martha Graham, and you can feel her in the picture.

And your new book is called Lost Time. And I’d love to ask you why the title of Lost Time and how did the book come about? And you’ve done other books before, of course, but this one, tell me about that.

Well, in about 2009 I wanted to make a book of my work collected work, and I didn’t have any idea how to do it. So Andrew Wylie, who was my agent, said Mark Holborn, who was a designer and a sequencer of photographs, he’s done all kinds of magnificent books. I think he also worked with Mapplethorpe and he did The Democratic Forest of Bill Eggleston, he’s done books on Penn, he did the Catalogue Raisonné of Lucian Freud, and he’s got great stature in the publishing world. And at the time he was working in-house at Random House in London. I went to see him at his house in Sussex, and I said I liked him and whatnot, and he agreed to come to New York to work with me for three days, it was from a Sunday to a Thursday. So we went out to dinner that Sunday when he got there in June and then Monday morning I got a phone call from London that said, “You’ve got to come to London. There’s this assignment for the 100th anniversary of Tatler. Come through. We got all the 10 Dukes together tomorrow.”

So I left him there and he said, “No problem. Not a problem.” I didn’t really believe him, but I thought whatever. And I came back a day later, I did the whole thing in less than 24 hours, and he said, “I’m not done yet.” I said, “What about the collaboration?” He just said, “Don’t worry, I’m not done yet.” Then it was Wednesday night and we had another dinner, and he handed me this compilation of photographs, a sequence. And on a Thursday after he left, I looked at it, I didn’t expect much, and I really loved it. It was a narrative sequence that told a story that if one looked at the book from the beginning until the end, the way one reads from left to right gave a satisfaction that was akin to reading a short novel or something, but purely visual. And one was at a loss for words, but one felt one understood something, and really it was my trajectory. And then no one wanted to publish it that way.

Okay. Why not?

I think they [other publishers] wanted to make a more conventional thing with a portrait section and a landscape section, I don’t know what, an artist section, a writer’s section. I wanted this book published Holborn’s way, and it didn’t matter. I made a dummy of it, I put it on a coffee table and forgot about it. Steidl agreed to do it and then something happened with his overseer Karl Lagerfeld and he didn’t like it for some reason, so he got in the way of Steidl’s printing it. I kind of forgot about it for a long time until a friend of mine, Steven Aronson, came by and he looked at the book and screamed at me and said, “You’ve got to get this published.” And then he said, “Go to Phaidon.” And he said, “Go see Billy Norwich.” And he was an old friend, so I called Billy Norwich, the next thing I know, Phaidon agreed to do it. I had published a book in the interim about 30 years at Vanity Fair, which was very successful, but it was Vanity Fair, not me.

And so this has been cooking for quite a while?

And so the Lost Time came about because I’d given Mark that book that Brassaï written on Proust and photography, and he was keen on it. And then I asked Mark to write a preface to the book that he’d sequenced. It’s his book in many ways, it’s his narrative, just my pictures. And everyone said, “No, you can’t have the designer [write the preface]…” But I did that. And then I read what he wrote, and it was all about Brassaï and about Proust. But I said, “Mark, this is a book about moi. What’s going on? You hardly mention moi.” And then I realized, well, it’s all my pictures, why does he have to mention me so much and what a great context he’s put me in, and it’s a context that I couldn’t realize myself. And then he titled his essay Losing Time, which I didn’t like very much.

And then we were looking for a title. He’d suggested other titles for the book. Plaisir was one, it’s French and not everybody knows quite what that means. It was that portion of Brassaï’s work that couldn’t be published for so long. He called it Plaisir. I don’t know. Then I said, “Well, why not just call it ‘Lost Time?’” And Mark changed his introduction to call it Lost Time too. I think it works.

Is there anyone that you look back on the portraits in this book, I’m wondering, that just give you a chill?

Oh, lots of people.

One of my favorites is of a young Rupert Murdoch and Roy Cohn shot in black and white in a party for Reagan’s, I think, reelection, inaugural looking quite—

They look like killers, don’t they?

Yeah, they sure do. I would say that one is the one that gives me the most…

I’m completely unaware of being in the presence of dangerous people. I’m intrigued with it.

Photography is something that is continuing to have a little bit of a resurgence now in a a post iPhone world or whatever you want to call it, and people are just rediscovering it and bending technology to their will and all sorts of things. I’m just curious, what is your take on the world of photography today?

I think it’s over, unless you really just stick to the film, you don’t have any basis anymore. And I’ve been whining about this for… It doesn’t do any good. I love the idea that what makes photography unique from any other form, art form or journalistic form or anything, is that it’s a document and it’s unassailable. And if you can alter a picture, it’s no longer a document. It becomes meaningless, it’s a very poor medium for illustration. I’d much rather see a drawing or a painting, much more romantic than a digitally altered photograph. And there was a fella up at I think it was Cornell who was like-minded, but really it’s Adobe that makes these Photoshop programs that become harder and harder to recognize as products that alter. The alterations, at some point they made a system where you could reconfigure the pixels to make the fact of its having been altered undetectable to just simple magnification. There’s no digital verification tool, I don’t even know if the FBI can do it anymore, that can tell you if a picture’s altered or not. And so I have no use for that business.

And so what is your shooting life like today? What kind of-

Well, I use film still and I use digital, I don’t alter it. If I don’t have film, I can’t prove it. People presume that everybody alters everything all the time. You have to scan even film, which makes it a nuisance.

It’s all laid out digitally, I guess.

Everything’s digital. Submissions to magazines have to be digital. I have to print from a digital file. So it’s all right. It envelops you. It takes you in.

And when you’re just not on assignment and you’re just maybe taking a trip or just in your daily life, do you like to just bring a camera with you where you go? Or do you keep that professional?

I pull a camera out when I want it. I don’t carry a camera around my neck. I never did.

When you travel, what’s your go-to camera? I’m curious when you’re—

My Rolleiflex.

Oh, okay.

I still use it. I don’t make a big distinction between work on assignment and anything else I’m doing. It’s just that I’m given an assignment, that’s all. I could go over there and do that.

And if I had to boil your approach to photography to three words, what would you say?

Don’t belabor it. Keep it simple.

Thank you to my guest, Jonathan Becker, as well as to everyone at Phaidon for making this episode happen. The editor of The Grand Tourist is Stan Hall. To keep this going, don’t forget to visit our website and sign up for our newsletter, The Grand Tourist Curator at thegrandtourist.net. And follow me on Instagram @danrubinstein. And don’t forget to follow The Grand Tourist on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you like to listen, and leave us a rating or comment. Every little bit helps. Til next time!

(END OF TRANSCRIPT)

A great design or art fair sets the tone for the year, defines the conversations, and points to where taste is headed. These are the fairs defining 2026. Save the dates.

We assembled our favorite design objects for the people on your list that have everything, including taste.

We checked in with our former podcast guests who will be inching through Miami traffic, unveiling new works, signing books and revealing new projects this year.