Mark Your Calendars: The Grand Tourist 2026 Guide to Art and Design Fairs

A great design or art fair sets the tone for the year, defines the conversations, and points to where taste is headed. These are the fairs defining 2026. Save the dates.

Welcome to The Curator, a newsletter companion to The Grand Tourist with Dan Rubinstein podcast. Sign up to get added to the list. Have news to share? Reach us at hello@thegrandtourist.net.

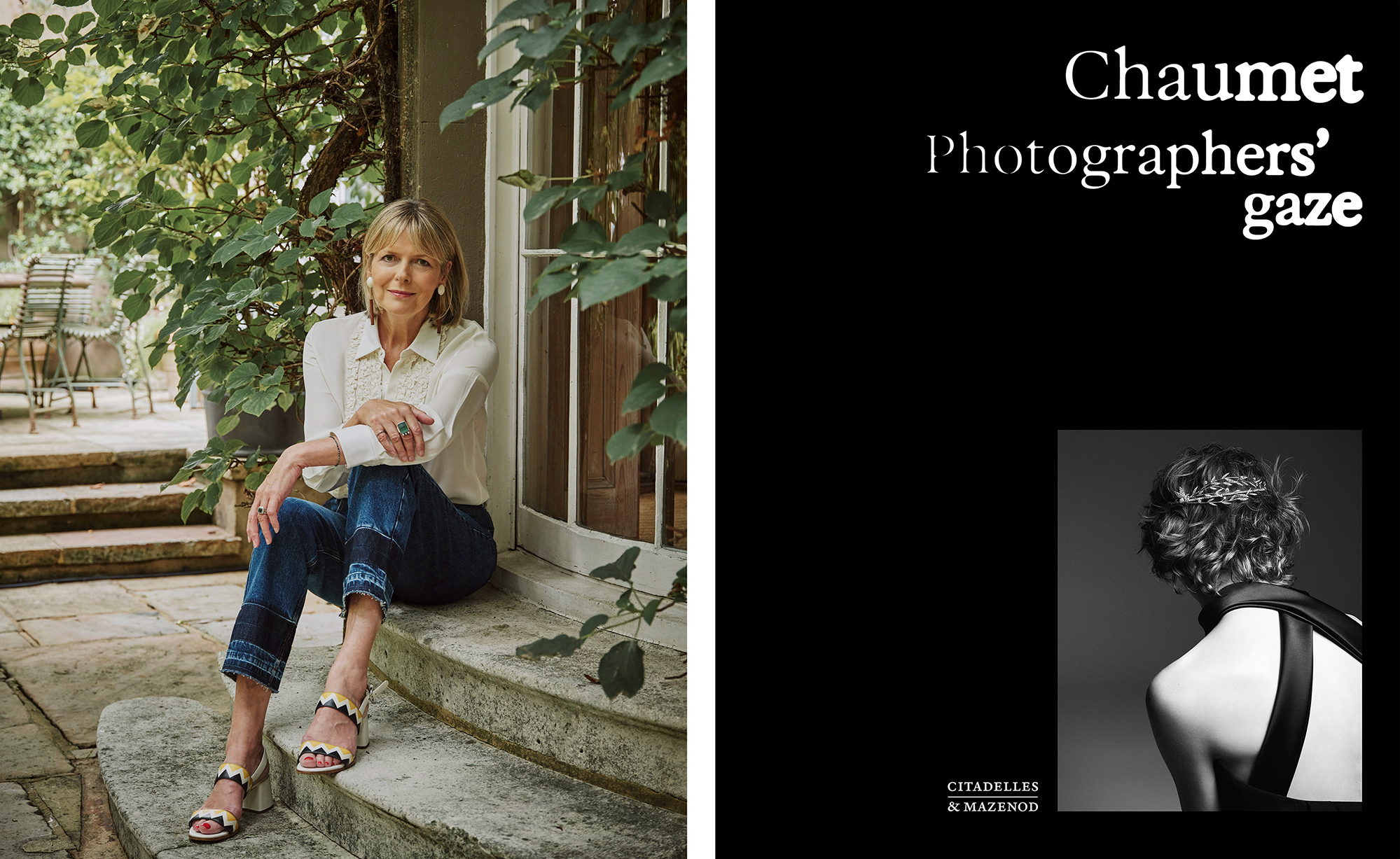

Chaumet, the jewelry house established in Paris in 1780, and resident at 12 Place Vendôme since 1907, is a veritable jewel box of history, politics, glamour, and, of course, tiaras. As the famed jeweler to the royal court, Chaumet bedecked French emperor Napoleon and his first wife, Josephine, in the gold, diamonds, and pearls that we see in so many symbolic paintings of the pair. But then, as Carol Woolton, jewelry editor at British Vogue for 20 years and still a contributor, says in a new book, “Chaumet: Photographers’ Gaze,” “Jewelry in images offers a closer glimpse into society itself, a glittering guide to fast-changing modes and the mood and style of an era.”

And while Chaumet creations exist in neoclassical art collections across the globe, it is the maison’s early embrace of realism that this book explores in detail. It was in the dying days of the 19th century when Joseph Chaumet made the move to establish an in-house photography studio. Flora Triebel, one of the book’s three key contributors and a curator of photography at the National Library of France, highlights the extent of this early innovation’s impact: “In all its scope and complexity, Chaumet’s photographic heritage, which has miraculously survived to the present day, is an important resource: 211,000 prints, 22,000 glass negatives, and 34,000 film negatives are stored in the maison’s archive.”

And so “Photographers’ Gaze,” which considers images and editorials from 1934 to 2020, presents us with points of view on the house through the lens of legendary photographers including Horst P. Horst, Guy Bourdin, Raymond Meier, and the star duo Inez van Lamsweerde and Vinoodh Matadin. In her years at British Vogue, Woolton, who is also a historian, author, and broadcaster—her own book “If Jewels Could Talk” was released this fall—has worked with a few of them. In her introductory essay to this new Chaumet book, she says: “In the wide pantheon of camera work, jewelry is notoriously a difficult subject.” I caught up with her in London and asked how she spent decades making jewels ready for their close up.

Gleaming gold and big, juicy gemstones—jewelry is a dream subject. So why is it so hard to capture on film?

Well, jewelry is precious in many ways, and it needs to be handled with care. These days that means a studio filled with security guards watching our every move. But it wasn’t always like this. In the 1950s and ’60s when Henry Clarke, the Vogue photographer, was shooting couture, there was a whole society of people that wore high jewelry, and so he could pop out and shoot wherever. You didn’t need security. When I worked with fashion editors Lucinda Chambers and Kate Phelan at British Vogue throughout the noughties, they never wanted to shoot jewelry because they were traveling, and being on location usually meant shooting fast. It just isn’t feasible to move high-value jewels around easily. So not being able to go on location is a barrier that makes the jewelry editor’s job incredibly challenging.

Locations are often the main character in a magazine story. If you can’t travel, how do you solve the conundrum?

I used to come up with a strong narrative idea that I could imagine over six pages. One of the shoots I created with photographer Raymond Meier, whose work is featured in the book, was a story called “The Morning After.” The idea was of a girl who’d been out too late the night before. She was too tired to take off her jewelry and woke up in bed, bedecked, in the morning. The first thing she needs is eggs and bacon, and then she’s slightly mopping her brows, and so on. Her hangover played out across the pages. I love doing stories like that. Other ways I’d approach a shoot was if there wasn’t a fashion trend that suited jewelry at the time, I’d make one. I remember the time when I wanted to do a “Winter Whites” story, yet none of the watch companies offered white straps. None. The reasoning was that white straps might get dirty too quickly. This was before the white ceramic Chanel J12 arrived in the early noughties. So I persuaded one of them to create a white strap, because you must always have something to say.

There’s a big difference between jewelry shoots and fashion ones. I mean, you can’t just put high jewelry on a model and make it part of a fashion story, can you?

Well, as I say in the book, jewelry photography is a more complicated assignment than portraying almost anything else we wear because the fluid nature of clothes allows them to be artistically draped or wrapped in a manner that’s not possible for the uncompromising metallic forms of jewelry. Fashion jewelry or accessories don’t have a complex inner life to explore and portray, whereas the depth of a gemstone needs precise lighting to ignite its energy and vibrancy, and it is constantly changing and catching the light as it moves. The skill and challenge for the photographer considering a weighty jewel’s three-dimensional volume and sparkle is to show depth and detail on a flat page. Vibrant gemstone colors must be replicated as true to life as nature created, and each tiny pavé-set diamond must shine, as a tiny fingerprint on metal or stone can turn even the brightest gem into a dark smudge.

Clothes can overwhelm jewels in a shoot, not least because with fashion there really must be some movement.

Yes, in the creation of a movement, we lose the jewelry a bit more, because you don’t want to photograph a dress just straight on. You’re going to bring it alive, to show the sheen, to show how it tucks in at the waist, so you’ve got even more scope for the jewelry to get totally lost, and that is very challenging. I think Chaumet campaigns are very effective in this way. If they use fashion, it’s very, very simple, because it’s about the jewel. It’s about where you wear it, the way you wear it, and how a great photographer creates something in the air that just feels a little different to fashion.

I know it’s a tough call in a book teeming with 20th-century greats, but we’re going to ask you anyway: Can you single out three photographers inthe book whose shooting style strikes you most?

First, Guy Bourdin. Well, he just captured an era, didn’t he? Back in the 1970s, his images managed to capture a casual feel that was glamorous yet so completely of its time. Bourdin’s photography was fun, funny, and sexy. There’s one 1979 image of his for Vogue Paris that I always think about—it’s in the book—a cat burglar creeping over a door, with a Chaumet necklace wrapped around her fingers. It’s so witty, so beautiful. Honestly, I wish I’d styled that. I think the models in his stories always look like they are having fun. They were wearing the jewelry, but they were enjoying it, and it was sexy.

Then, Julia Hetta. Her style is just so whimsical and beautiful. I worked with Julia on a shoot for British Vogue where we created incredible still-life images, like an old master painting, across six pages. Each one was different, and they had this gorgeous stillness about them. She was placing jewelry in these unusual spots on the body, like a little butterfly that had just landed for a moment. You’d look at it and think, “It’s not going to stay there long—it might fly away any second.” It was natural, delicate, and stunning. What makes her work so special is that she is always finding beautiful new ways to show jewelry, and that stillness, even on a model, as you see in her images in the book from 2018 to 2019, is so powerful.

Last but not least, Rankin. His 2003 campaign for the Chaumet Class One watch, which is a super close-up of the model’s straight fringe and eyes, one of which is covered by the watch, captured a whole narrative about women’s lives changing. It seemed to say: “We’re doing it all, and time is precious.” That’s what it was for me—like, “Here it is, I’ve got my eye on the time.” It reminds me that the Class One was a real classic. What I love about Rankin’s point of view is how he tied into this whole girl-power vibe. You know, like the other Ellen von Unwerth shot in the book, where a woman sits between two boxers—one of them with a jab to the eye—and she’s there, just cucumber-cool. It just nailed the girl-power energy of the time. Each era highlighted in the book has told a little story about how women live. Like that image with the tiara tilted on the back of the head. It says, “We make these beautiful headpieces, but you don’t have to be traditional anymore.” Life’s moved on. Jewelry isn’t just about status now, it’s about style. Rankin really captures that shift, and I love it.

Would you agree that the way a photographer perceives jewelry in a magazine shoot can also ignite a trend?

Yes. The trend for men wearing brooches in different ways on the red carpet is a good case in point. If we look at photographer Timothy Schaumburg’s story in the book where the young male model wears a Chaumet diamond carnation brooch pinned to a shirt collar as an alternative to a white tie, it has a transgressive feel. It’s so chic. Because, you know, you see shoots where it looks as if a stylist has just told the model, “Here, put this on,” and it feels so forced, so inauthentic. And honestly, sometimes with these pieces, you don’t need to scream “latest fashion.” Just let it be about the feeling, the mood. That’s enough. I think the trouble is, with a lot of fashion shoots with high jewelry, it’s portrayed as a sort of grand lifestyle. People who buy high jewelry don’t dress like that. I mean, I don’t know anyone who lives like that, do you?

Basquiat’s Swiss Inspiration; Artists Across the Black Diaspora; Plus More Openings

Los Angeles, “Imagining Black Diasporas: 21st-Century Art and Poetics” (Until Aug. 3)

Artists working across the Black diaspora are often described as reconnecting with and preserving their heritage. This exhibition emphasizes the creativity and reinvention that this process entails, from South African artist Igshaan Adams’ woven and beaded sculptures and Guyanese painter Sandra Brewster’s large portraits of blurred faces, to Widline Cadet’s poignant photography centering on her experience emigrating from Haiti to the U.S. Exploring the diaspora as a source of creativity, this exhibition brings together 70 paintings, sculptures, photographs, and multimedia works by 60 artists. lacma.org

New York, “Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe and the Last Gullah Islands” (Until May 2025)

On the southernmost coast of South Carolina, there’s a small three- by nine-mile island, Daufuskie Island. In 1977, American photographer Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe photographed the island and its inhabitants, the Gullah Geechee, most of whom are descendants of former slaves who acquired land from white plantation owners after the Civil War. Real estate developers were closing in on the island, threatening the unique culture at home there. A selection of Moutoussamy-Ashe’s photographs on view here preserve a community on the brink of change. whitney.org

Prato, “Peter Hujar, Performance and Portraiture / Italian Journeys” (Until May 11)

Andy Warhol once called photographer Peter Hujar “the boy who never blinked” after taking his portrait. Hujar turned the same patient gaze onto the people, places, and animals that surrounded him in New York’s downtown art scene of the ’70s and ’80s, stealthily capturing the essence of things. Almost 40 of these photographs from New York as well as photographs from Hujar’s travels throughout Italy are presented together in this richly varied collection. centropecci.it

Rome, “Gerhard Richter: Moving Picture (946-3) Kyoto Version” (Until Feb. 1)

Gerhard Richter’s incredibly varied output makes him hard to define as an artist, though the label “greatest living painter” has sufficed. The German painter’s trademark blurs the line between image and painting, reproducing photos with an eloquent blur. In 2010, Richter started the Strip series, where he digitally split images into thin multicolored stripes. Now, Gagosian Rome projects their entire space with Richter’s latest addition to the series, an immersive film that’s accompanied by a trumpet score. gagosian.com

St. Moritz, “Jean-Michel Basquiat” (Until March 29)

In 1982, Jean-Michel Basquiat traveled to Switzerland for his first European exhibit opening, in Zurich. He would return more than a dozen times to St. Moritz, Zurich, and Appenzell between then and his premature death in 1988. Basquiat was taken with Switzerland, particularly the tranquil Engadin region, and introduced alpine trees, white mountains, and skiers amid the themes of Black history in his paintings. Examining this unexplored side of Basquiat, Hauser & Wirth, St. Moritz brings together “The Dutch Settlers” (1982), “Skifahrer” (1983), and “Big Snow” (1984). hauserwirth.com —Vasilisa Ioukhnovets

A great design or art fair sets the tone for the year, defines the conversations, and points to where taste is headed. These are the fairs defining 2026. Save the dates.

We assembled our favorite design objects for the people on your list that have everything, including taste.

We checked in with our former podcast guests who will be inching through Miami traffic, unveiling new works, signing books and revealing new projects this year.