What to See, Experience, and Explore at Miami Art Week 2025

We checked in with our former podcast guests who will be inching through Miami traffic, unveiling new works, signing books and revealing new projects this year.

This article is from our first-ever print issue, available for order online now.

I first met the Italian photographer Alessio Boni when the podcast used a portrait he took of rock-star interior designer Pierre Yovanovitch. It was then over Instagram that I discovered his fine-art work, which was somewhat new for him at the time. Once I began planning for this first issue, I knew that I wanted him involved (he also shot the designers of Studio KO, who raved madly about his skills to me afterward). Boni, 42, who is based between New York and Paris, started shooting at an early age and stumbled upon a career in fashion mostly by accident. He’s contributed to magazines such as Vogue Italia, Interview, and GQ, and he’s done campaigns for brands like Miu Miu, Gucci, and Jean Paul Gaultier. As a boy who escaped an ordinary life in the town of Supino, about 45 miles southeast of Rome, for a life of glamour, he assigns special meaning to his adopted second home of Gotham, as a place of creative and personal freedom. It’s something you often hear from contemporary Italian expats in the U.S.

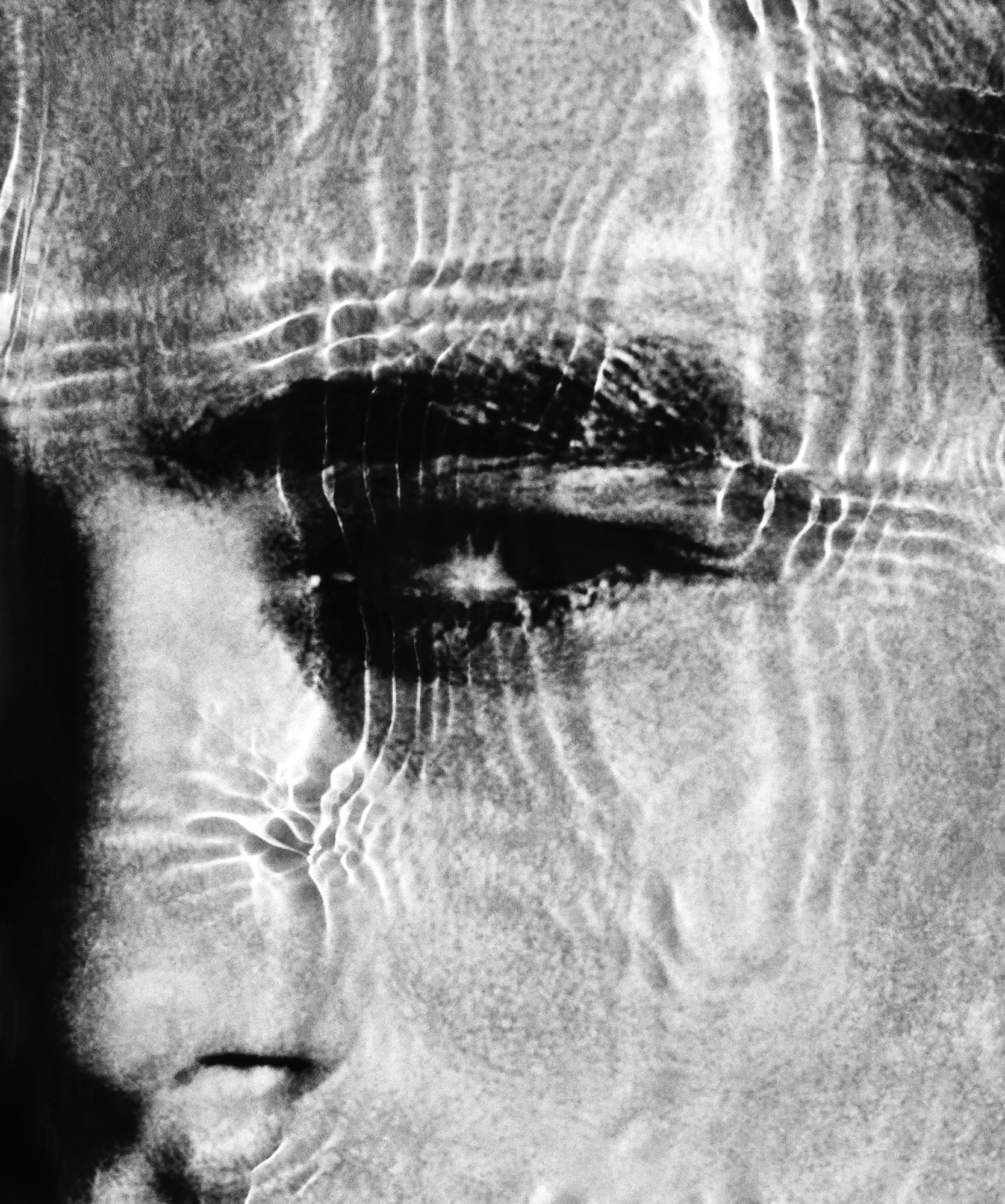

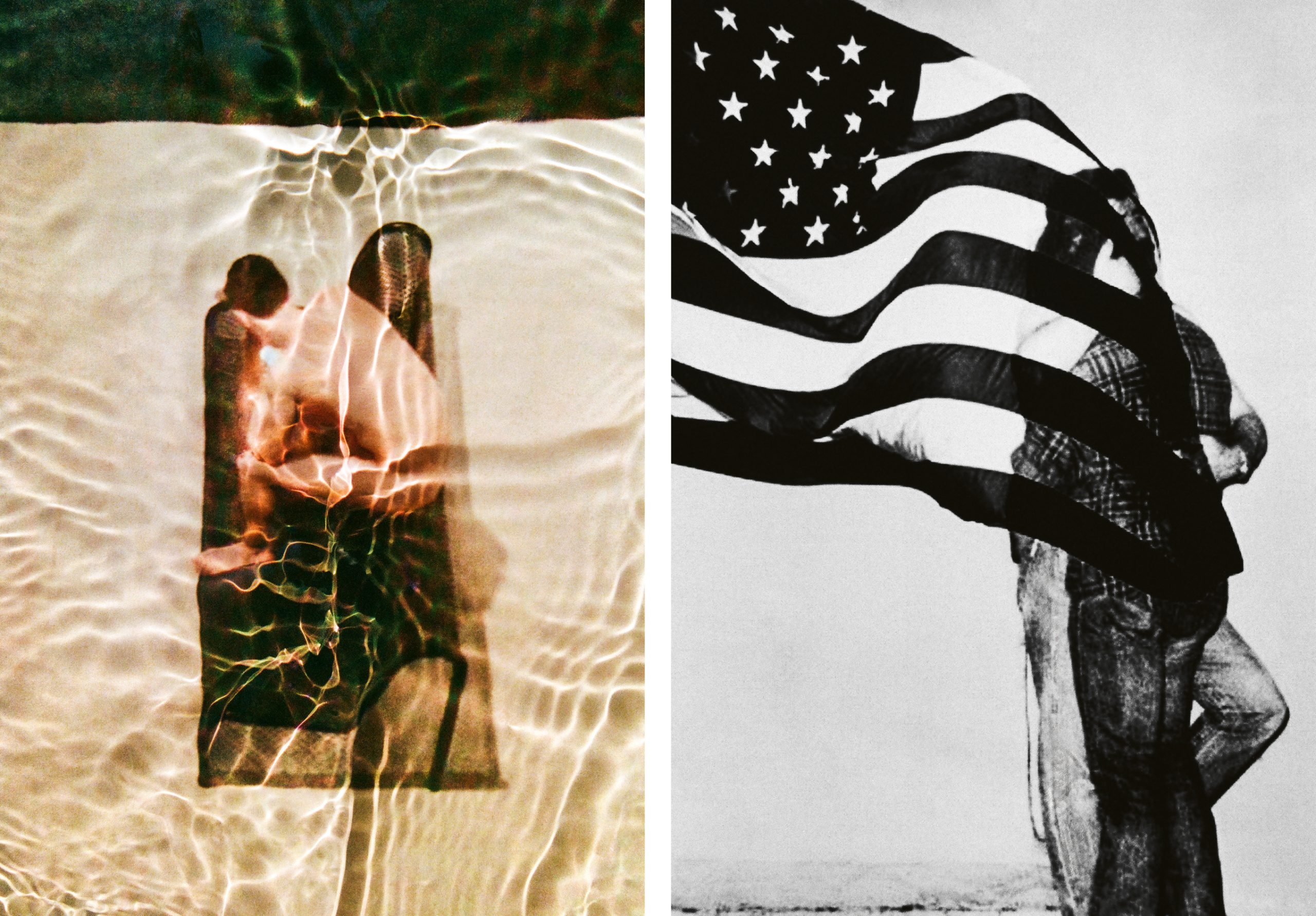

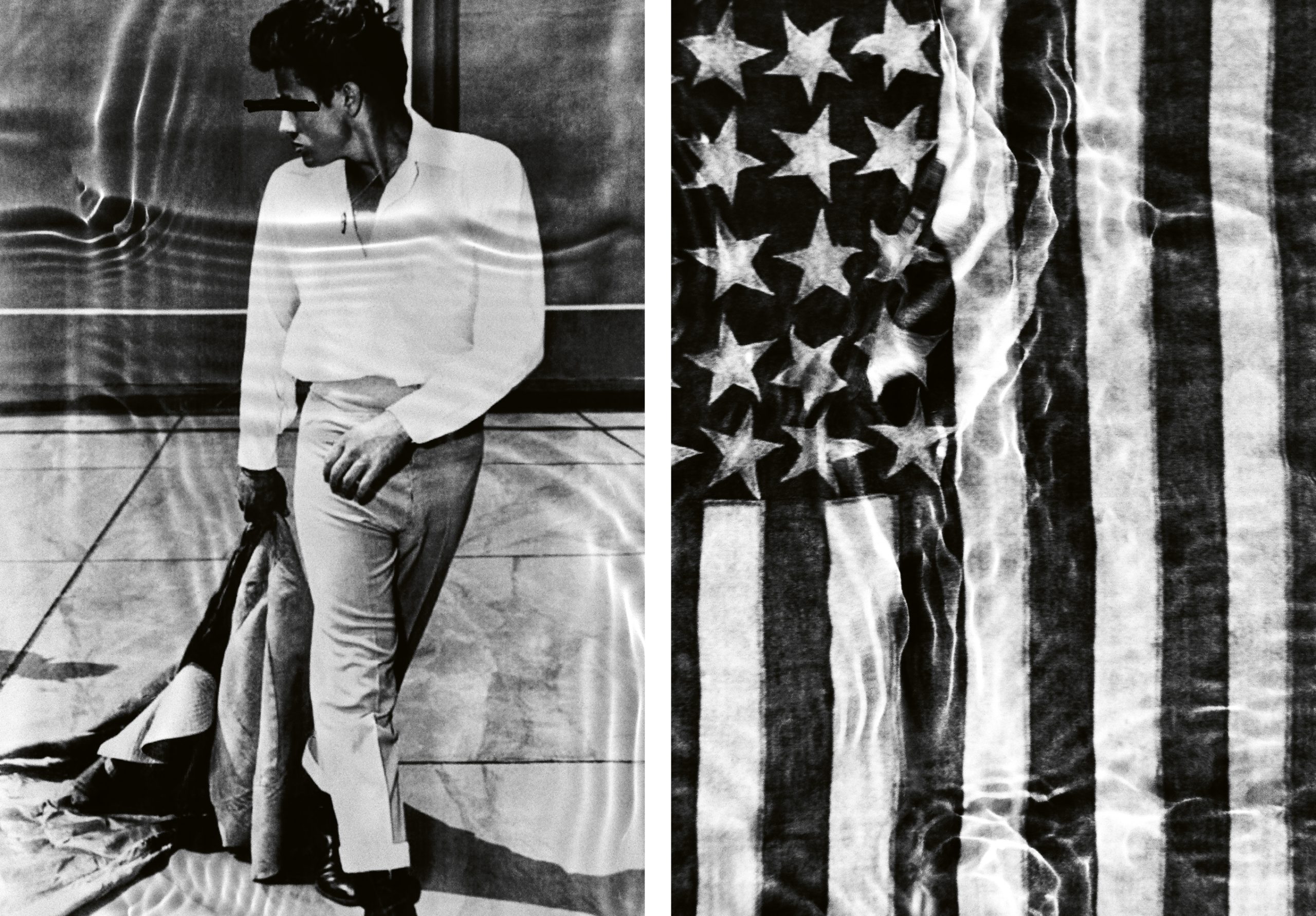

Using a multistep, mostly analog process involving little pools of water, he creates his dreamlike, mesmerizing photographic artworks. Since Boni is a creative soul who works in the borderlands between art, design, and commerce, I knew he would be the perfect person for this first print issue of The Grand Tourist to create The Idea of the Past Is Immutable, a portfolio that speaks not to his own personal tale, but to the City of New York we call home, like a kind of spiritual travelogue. After seeing the following works for the first time, I spoke with Boni from his flat in Paris to discuss his unpredictable career, how L.A. shocked his pedestrian-friendly Italian sensibilities, and what American life means to him.

So you’ve been a professional portrait and fashion photographer for how many years now?

Well, I’ve taken photos since I was very young, about 15 years old. And I’ve been taking photos professionally for 14 years. But when it comes to fine art, it’s very new. It’s been only two and a half years.

Was there something in your life that sparked this idea to branch out?

Yes, definitely. It was a moment in my life when I was looking for a big change. I left New York after 17 years and went to Paris to keep doing what I was doing, but when I got there I realized that I needed something different, and something practical. Photography was becoming computer work, mostly. It would be one day of shooting and then one month sitting behind a computer. I wanted to do something where I could use my hands more, so that’s why I came up with this technique that involves physical elements like water and ink and paint. But of course in the aftermath of all that, I’m still back at my computer, but there’s a lot of physical work that comes with it, too.

Do you remember the first time you picked up a camera?

I grew up in the south of Italy in a very small village in the mountains, and my luck is that my dad was passionate about photography, so he had cameras, and his brother, my uncle, was even more passionate. He had a darkroom and an enlarger and all of that. Then another uncle on my mom’s side was also very passionate about photography. In the 80s and 90s it was more common, because better cameras were coming out, and people thought they could do what only professional photographers could do in the past. I was lucky enough to have it all around me, and my dad started loaning me his camera when I was 12 or 13 during a school field trip. I was the only kid with a big reflex with lenses. But I didn’t take that many pictures until I moved to Rome when I was 18, 19. When I moved there, I was with my best friend at this wine bar. In Italy, you can drink when you’re 18. We were at the bar—and it was kind of fortuitous because it was a place where everyone from the movie industry would go, young actors—so we were there because we wanted to see what was going on. We met this girl, and she said, “Ah, you guys are cute. Do you want to model at the photography school in Rome?” And we were like, “Fuck yeah, this is the chance of our lives!”

So we went, and I was mesmerized because I’d never been on a set of any kind, and I saw lighting and all these people taking photos, and I couldn’t care less that they were taking photos of me. I wanted to take the photos myself. I was jealous of them. From that moment on, becoming a photographer became my mission in life.

After that I looked to assist someone, since my other job was trying to be an extra in the film industry in Rome, so it was easy to fit in. I met a lot of costume designers and all the people that were rotating around the business. I met someone that introduced me to this photographer, and he was the first one I assisted. I was just 19. I did other jobs: worked at a restaurant, production assistant, casting for extras, all of it. And while I was doing all of that, my camera always came in handy in getting more work. Then, when I was 23, I realized that Rome was not really the place to make this thing happen, to become a photographer, so I decided to move to the U.S.

What was that like for you?

I arrived in Los Angeles in 2006, before social media, before Los Angeles was cool again. At first I was like, “Oh my God, where the fuck am I? I can’t even walk to the grocery store here.” I was just so used to European life, especially Italian life where you’re in a city, you sit at the piazza for coffee, and you walk everywhere. So I had this terrible cultural shock, but at the same time I started being so mesmerized by so many things that I’d seen in movies my entire life. I started taking day trips to the desert, to Vegas, and L.A. was so photogenic everywhere. I started thinking of totally different kinds of photos. Fashion photography was never my goal, I have to be honest. To me it was always that I loved taking photos, and it was an urge and a necessity, but I didn’t have a goal, or someone I was really looking up to become that person. I just followed what I was feeling. Later on, I went to New York to experience the city, and that’s when I started assisting fashion photographers. It was just a necessity called upon by my need to take photos.

Your personal work is deeply, well, personal to you.

Yes. I always see the elements that live there. If I look back on my work, my personal work is completely homoerotic, a mega celebration of the male body, and it was really what helped me to express myself to everybody. At one point I started taking photos of guys, naked guys or experiences that were very personal to my life, and they were referring to that kind of sexuality. I made a decision that I was really coming out because then, at that point, there was no doubt anymore that I was gay because of the photos I was taking. For me, that part stays and remains important to me because it changed my life, and I always say that I was very lucky to be in New York with a camera in my hand. And I could have this mega freedom of expression. When I look at my work now, it’s that male element in particular that’s always present. It’s about sexuality. The thing is, after many, many years, I don’t need to literally translate that into an image. A car on fire can be sexual for me, the same goes for a palm tree on fire, same as a runner from the 1943 Olympics, because it’s the male body.

And tell me about this technique of yours, which is quite unique.

It’s multimedia in the sense that it involves a lot of different media, digital and non-digital. I do a lot of research for different old images; some are from my archive, some are photos I take with my iPhone, and some are shots of videos that are on TV, on the laptop, et cetera. And some are public-domain images. Once I have the images, sometimes I do some post-production on them. I put images together, or I make changes to them. Then I print them on cheap office paper. And then I put them in a tray that’s full of water. Then I rephotograph everything under sunlight with a film camera. And so, in the process of rephotographing everything, I sometimes add pigments or ink. Sometimes I add it into the water, or directly onto the paper. The final product is a real analog film photograph. It doesn’t get more real than that.

Why film?

Because it’s always been one of the pillars of my career. I started in film. I shoot digital for other stuff, too, but when it came to these artworks, I decided to try and do it in film because of how it made me feel. And I love the grain created when I print them, too.

Has working on your fine art helped the fashion side of things?

Yes. It has definitely put my brain in a brand-new age for me in terms of creativity. It gave it a big shift. It pushed new buttons that I didn’t even know were there. It’s a lot of stimulation, a lot of extra thinking. I think that if it has any benefit in my fashion work, it is just because it made my brain healthier, in a moment where perhaps I was burned out creatively.

And the series is, as you mentioned, kind of a love letter to the United States.

It is. I’m very happy you said that.

And it contains moments of joy and liberation but also horror and oppression. Is that fair to say?

Absolutely, yes. And I have goosebumps that you said that because I wrote a few pages today before the interview to try to explain this new series, and you really went to the core of it. Wow, thank you. Because when we started talking, I said, “Okay, I really want to pay homage to New York.” So that was my starting point. And so I started to think about what New York gave me, and of course again, my sexual freedom and liberation came into the discussion with myself. I started to think about what New York meant to the history of art, what role it played in the gay rights movement, and how big it was for the freedom of expression in general. In the end, there’s always something for everybody there.

And so I started looking into places, the infamous piers, and all of that. But of course, I didn’t want to be so literal because I didn’t think it’s necessary. While I was doing all this research, and I started shooting some stuff, the election started to happen, and my heart started to ache thinking of America and of this place that’s my second home that has given me so much. That’s when it really became a love letter to America.

It’s funny you mentioned the election because my next question was about how it’s clouded many people’s outlook on just the idea of America. As someone who lives part-time in New York and part-time in Paris, have you felt any kind of shift in New York?

Well, the thing is that this big shift has been happening in Europe, too, unfortunately. We’ve seen a huge rise of right-wing populism, anti-Europe, pro-Russia, and all of that, plus everything that’s happening in the Middle East. So unfortunately, the election of Trump is not as shocking as the first time around. What I can say is that New York, fortunate for us, it’s kind of a safe bubble in that sense. It’ll never become a Republican town. It’s impossible. New York will always stay the same, but when there is this darkness in power, you always fear for your freedom.

Speaking of New York, can you recall when you first arrived here and really felt that sense of newfound freedom?

Well, I got out of the subway the first day, and I saw the people around, the diversity, the way people were dressed, the way people were not looking at each other, the way people were minding their own business, and I felt right away that that was a place where everybody could cohabitate together. Once you’re in a place like this, you start thinking, “Okay, okay. Yeah, I can be safe here and maybe even start saying who I really am.”

We checked in with our former podcast guests who will be inching through Miami traffic, unveiling new works, signing books and revealing new projects this year.

The ecstatic designs of Chris Wolston come to Texas, Juergen Teller's most honest show yet opens in Athens, a forgotten Cuban Modernist is revived in New York, and more.

Tom Sachs explores various creative disciplines, from sculpture and filmmaking to design and painting. On this season finale, Dan speaks with Tom about his accidental journey to fine art, how an installation in a Barneys window kickstarted his career, and more.