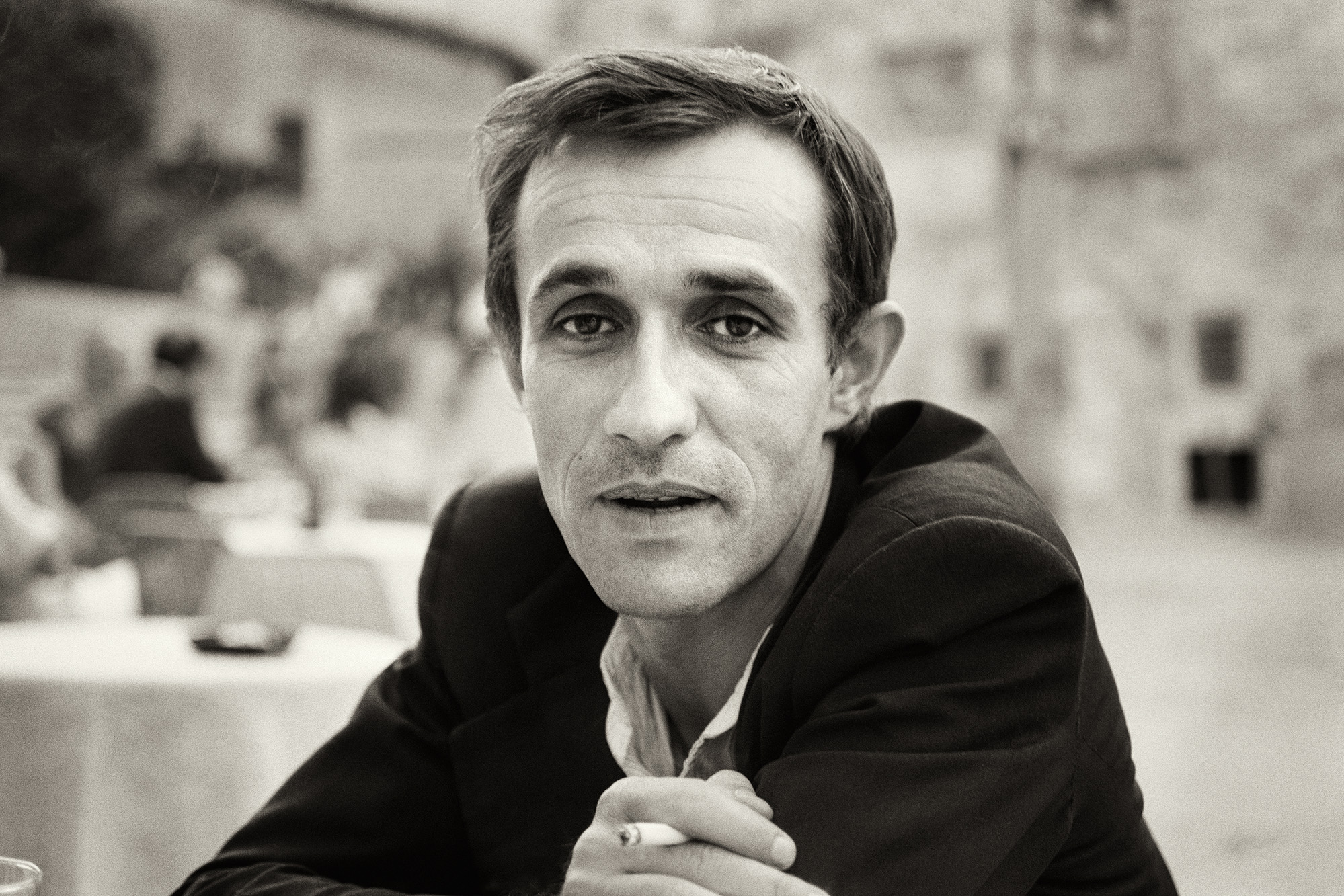

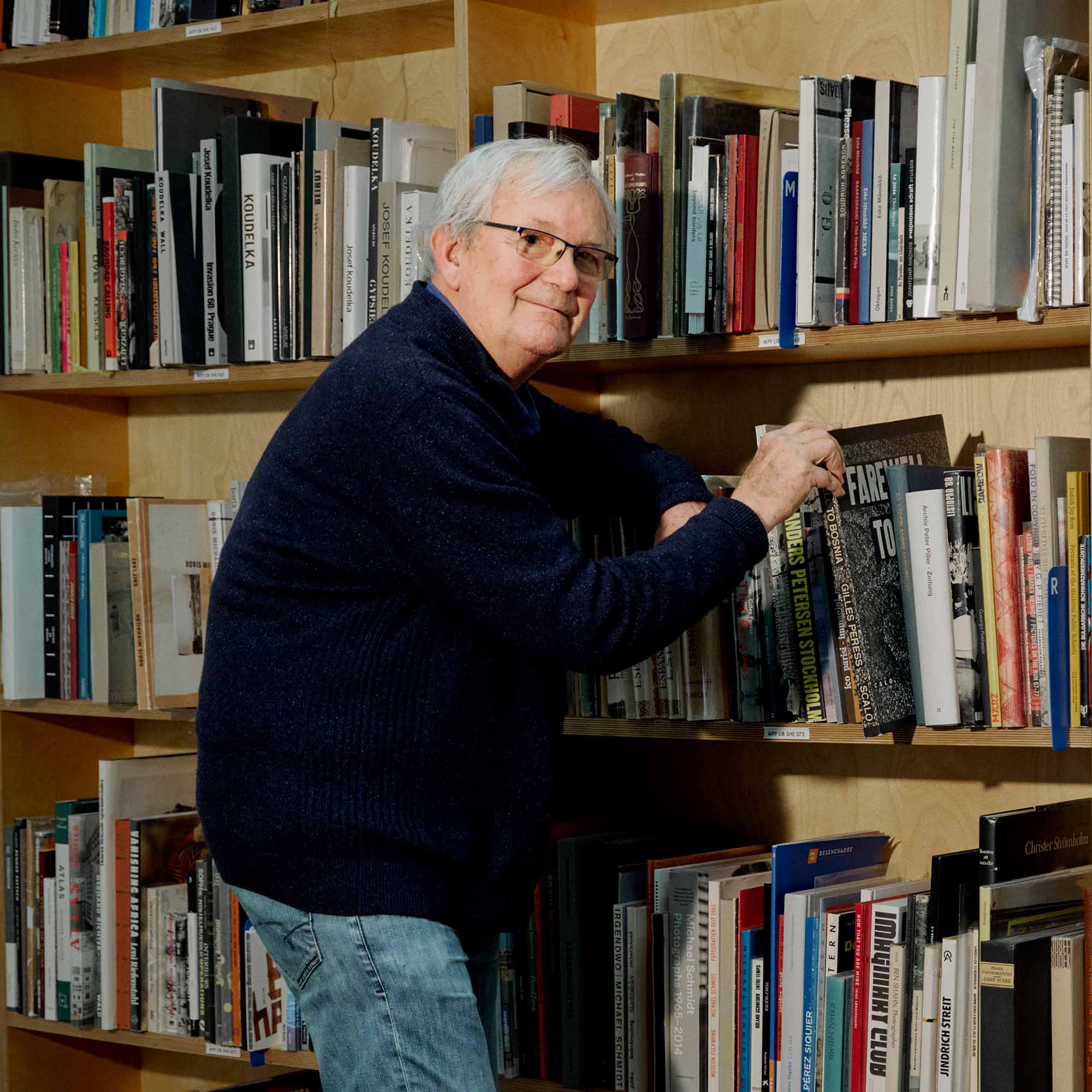

Martin Parr: A Photography Great Who Turned a Lens on Society

British photographer Martin Parr knew how to observe and highlight aspects of culture and contemporary life in both humorous and refreshingly honest ways.

Welcome to The Curator, a newsletter companion to The Grand Tourist with Dan Rubinstein podcast. Sign up to get added to the list. Have news to share? Reach us at hello@thegrandtourist.net.

Costume designer Sandy Powell has made a career outfitting period pieces. Her work ranges from projects that prioritize historical accuracy, like “Young Victoria” and “Gangs of New York,” to those that conflate eras, styles, and mannerisms for something more decadent, such as “Cinderella,” “The Favourite,” and “Shakespeare in Love.” In her debut exhibition at Savannah College of Art and Design titled Sandy Powell’s Dressing the Part: Costume Design for Film (on view now through March 16), the Academy Award–winning designer has had the rare privilege of examining a retrospective of her professional career.

At one end of the exhibit you’ll find a mink coat worn by Cate Blanchett in “Carol,” and at the other, a retro-futuristic vinyl set from “How to Talk to Girls at Parties.” In between, there’s the lavish corseted gown of Tilda Swinton’s from Orlando. Reflecting on her body of work, Powell says, “I’ve probably done the 1930s more than anything else, but each project is different. The story is never the same. Therefore, you discover new things even if it’s a period you’ve done before.” Seeing her work collected together, Powell has gotten a sense of perspective about her career. “I could definitely see a sense of humor as I walked around the exhibition,” she says. Ahead, I speak to Powell about the process of curating the exhibit, the projects she’s most proud of, and the joy of breaking rules. —Camille Freestone

How did this exhibit come to be?

The curator, Rafael Brauer-Gomes, contacted me two years or so ago asking if I was interested in collaborating on an exhibition with them. And I said absolutely. No one had ever asked me that before. It’s been really, really fascinating. At first, I wasn’t sure how much we’d be able to get to put in the exhibition. I do have quite a few pieces I have collected over the years, but I’ve kept them very badly, just shoved into bags or hung up in a storage space where I keep all my work stuff. I’ve never really paid it much attention. This forced me to go and have a look at what I had. I realized that I have quite a lot, over 70 costumes dating back to the very first film I worked on, “Caravaggio.” I knew that we could also find costumes in various other places, which is what we did over the next year and a half. We ended up with more than there was space to exhibit.

Where did you find the other pieces?

I knew the Angels, the costumers in London, had many pieces. Quite often, the film companies sell the clothes at the end of production to the costume rental companies. Once they buy a costume, it goes into their stock and gets recycled and reused. I work out of Angels a lot, and I know they’ve got billions of costumes. I knew which of my costumes were there. They keep principal costumes that they know are worth something separately. On the whole, they were never really allowed to be altered or changed that much. Everything from “Velvet Goldmine” came from there, which is incredible because that’s over 25 years old. They had things from “Young Victoria,” some “Shakespeare in Love.”

And then we also worked with a private collector called Larry McQueen, who lives in L.A. He is a fabulous character who is obsessed with costumes and has been collecting for a lot of his adult life. His collection is enormous and dates back to the silent-movie era. He’s been charming enough every time he’s purchased a new piece of mine to actually contact me and tell me what he’s got. He’s always sent me photographs of them, like he’s sending me photographs of my children, showing me how they’re getting on.

Do you get to keep any costumes after a project?

Technically, I don’t own my actual designs, let alone the costumes. That’s all owned by the production companies. Back in the old days when everything was very low budget and I was making half the costumes myself, no one really bothered if you took anything. I kept them as souvenirs back then. And I had a lot more that I’ve since lost because they were always brought out at parties, used for dressing up and going to nightclubs. Seriously, there were costumes of Tilda Swinton in this exhibition from “Wittgenstein” that have been used on multiple occasions. I’ve used them as costumes for a dance show. I’ve worn them myself out to parties. Yet they’ve survived, and they’re now hanging in this exhibition.

My collection on the whole is from smaller productions where I’ve asked permission to take something. On larger films, you quite often make multiples that aren’t needed, so I’ve been able to take some of them. Obviously, I don’t possess anything that’s come from major studio films like Disney. All the Disney costumes in the exhibit are on loan because they keep and archive everything. At least then we know where it is and that it’s kept properly.

What was it like being able to see so much of your work in one place?

Once we got everything there, people spent months sorting it all out, repairing all the damaged things. And then actually pairing the costume with a mannequin is the hardest bit of a costume or fashion exhibition. And it’s the bit that—if it’s done poorly—makes an exhibition not work. So they did all the hard work. I came in three or four days before the opening. I did all the final tweaking and styling and actually positioned the mannequins in the poses that I wanted.

I don’t think I actually stood away from it until just before the opening, when the room was empty and I could walk around on my own. It was quite extraordinary seeing the extent of it. It was really rather emotional because it was like seeing my entire professional life, which is almost 40 years long, there in front of me. It wasn’t just about the clothes, and it wasn’t just about the costumes and the films they came with and what they represented; it also reminded me of where I was in my life at each of those moments in time—what was happening, what I was doing, and what else was going on.

Could you ever have imagined when you were starting out that your work would one day be exhibited like this?

I think I’ve always hoped that there would be an exhibition. Obviously secretly, that’s why I was collecting. Otherwise, it would have been very, very difficult to have gotten so much of it together.

Did any themes emerge in putting the show together?

Yes, and sometimes it was other people pointing that out to me. There are a couple of colors that turn up all the way through. Even though they are from completely different projects, there’s something similar. And sometimes it’s hard to put your finger on what it is.

I saw in some interviews you said you could never pick a favorite because it’s like picking a favorite child. But you also said you love challenges. Are there any past challenges that stand out to you?

Every single job is a challenge. If it wasn’t, it would be a bit problematic. It means it’s too easy. It’s a challenge getting to the end of a project. It’s a challenge starting it. There are always obstacles and hurdles you have to overcome. And that’s before you’ve even started being creative. That’s even before you start having an idea. There is so much to navigate. I’m always asked to identify the biggest challenge. It’s challenging in that it’s hard and it’s stressful, but it’s a stress I enjoy. It’s a stress that I thrive on, I suppose, which is more like adrenaline stress.

I suppose “Gangs of New York” is a piece of work I’m proud of. It was the first film I did with Martin Scorsese, and I hadn’t worked with him before. It is also one of the biggest films I’ve ever done. The entire film was made and shot in Rome. So not only was I away from my regular team of people, I had to work with new people in a new way on a film that was constantly in development. It was constantly changing and being rewritten with new themes added. It was a bit like a roller coaster. Every single piece in the film is made from scratch. It was hard work but really rewarding and a really fantastic experience.

What is your research process like for a film? And how different is that from your day-to-day personal consumption?

I walk around with my eyes open. I think we all get inspired every single day. But the actual research process is pretty much the same on any project. It starts with looking at images. You consume as much as you can about the period. I look at a mix of images that directly reference the period and ones that I just like. I think you can get inspiration from anything. A lot of the time, I think inspiration is subconscious. Let’s say you’ve got a month between meeting the director for the first time and showing them a mood board or coming up with an idea for a design. Nothing gets on paper until the very last minute, and I’ve learned to not panic about that because actually what’s happening over that time is you’re soaking everything up. And then when the deadline comes, it comes out.

Would you prefer to work on a production that was more about accuracy, or something where a little stylization is encouraged?

Well, I’d say “Cinderella” was fantasy, quite honestly. I kind of made up what the period was. Once-upon-a-time period—it’s anything from the 16th century to the 20th century. I was doing the 1940s does the 19th century. Of course, I love that because it’s lots of theories all mixed into one. I do enjoy doing proper historical accuracy, but I think what excites me the most is being able to take risks and push the boundaries a little bit. So stylization is what I tend toward. I do think you have to understand the history though. You have to know the rules before you can break them.

In the world of fashion, clothing, and image-making, why do you think you landed in film and theater?

Because I like storytelling. I love clothes, and I love fashion, but I knew I didn’t want to be a fashion designer. As a kid, I loved dressing up and clothes. But then I also liked stories and storytelling in the theater. I realized I like dressing characters as opposed to making nice clothes.

When you get dressed yourself, do you think about yourself as a character?

No, I don’t dress myself as one thing one day and another the next. I dress to please myself.

Have any movies ever rubbed off on you regarding how you dress?

Yes. If I’m being honest, there might be some kind of fabric that I really love. For instance, on “Gangs of New York,” I used quite a lot of African print fabrics, and the reason I did that was because a lot of the prints were small florals and things like that, which reminded me of the kind of floral prints you get in 19th-century women’s clothing. And they were brightly colored. The Victorians were into really bright colors, and you don’t often see that. I used fabrics that I liked, and then I thought, “Oh, they’re nice. That could translate into something I could wear.” So I ended up making myself some shirts and then made shirts for other people. I get inspired by the things I’m making for the film, but it’s usually just in the case of textures and fabrics or maybe the shape of a jacket. It’s not too literal. My actual style doesn’t change.

Of all the characters you’ve dressed, is there anyone who dresses most similar to you?

I don’t do contemporary pieces, so that makes this difficult. I would if it was the right thing, but I tend not to. But you can’t help putting a bit of yourself in your work.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

What to See This Week by a Italian Photographer, a Turkish Opera Singer, and a Czech Literary Rebel

Berlin, “Semiha Berksoy: Singing in Full Color” (Opens Dec. 6)

Semiha Berksoy was the star of the first Turkish sound movie “Istanbul Sokaklari” (“The Streets of Istanbul”) in 1931. Soon after, her performance in the first Turkish opera, “Özsoy,” is said to have stunned Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the first president of the republic. Berksoy’s career as a soprano helped establish Turkish opera internationally, and meanwhile she became an acclaimed cultural symbol. She painted, too, privately at first but then gained increasing recognition for her introspective portraits charged with the same drama as her voice. This exhibition presents 80 paintings and works on paper, archival documents, video, and audio for the first time in Berlin, the city where Berksoy studied and became the first Turkish prima donna to perform on a European stage. smb.museum

London, “Priscilla Rattazzi: Between Worlds” (Until Dec. 20)

Through the ’80s, Italian fashion and portrait photographer Priscilla Rattazzi was shooting the likes of Diana Vreeland, Loulou de la Falaise, and Gianni Agnelli for “Vogue Italia” and “New York.” So in 2020, when Rattazzi went out West to photograph the dramatic endangered rock formations in southern Utah, she did so with the touch of a portraitist, capturing the sculptural landscape in a strangely moving light. The series, titled “Hoodooland,” is featured with Rattazzi’s work from 1975 to 2021, in her first solo exhibition in the UK. robilantvoena.com

Los Angeles, “Ordinary People: Photorealism and the Work of Art since 1968” (Until May 4)

The word “photorealism” first appeared in a 1970 catalogue for the Whitney Museum show “Twenty-two Realists.” Painters like Richard Estes and Audrey Flack adopted the camera into their art practice, rejecting the point of abstract expressionism for a different one. Instead, they opted to be as faithful to reality as possible, painting phone booths, gumball machines, cars, and palm trees in incredible detail. Gathering more than 40 artists, this exhibition follows the evolution of the genre into today’s image-saturated era, and widens its scope to encompass paintings, drawings, and sculpture. moca.org

New York, “Franz Kafka” (Until April 13)

When Gregor Samsa woke up one morning to find himself transformed into a giant insect in “The Metamorphosis,” he thought, “how about if I sleep a little bit longer and forget all this nonsense.” These forlorn words have not lost their resonance today. Kafka died of tuberculosis at 40, leaving behind a small but incredibly influential body of work. On the 100th anniversary of his death, this exhibition remembers the writer through his literary manuscripts, letters, diaries, drawings, and photographs. On show are the original manuscript of “The Metamorphosis,” his novels “Amerika” and “The Castle,” and a diary in which he composed the 1912 short story “The Judgment.” themorgan.org —Vasilisa Ioukhnovets

British photographer Martin Parr knew how to observe and highlight aspects of culture and contemporary life in both humorous and refreshingly honest ways.

One of L.A.'s architectural treasures is taken over by an artist that uses color and design; India Mahdavi creates outerwear that makes rainy days a joy; and Jeanne Gang builds a recreational center in Brooklyn that's sorely needed.

One of the most exciting parts of traveling today? The ability to disconnect. On this episode, we explore Ranchlands, a massive land management business in the American West that includes the remote Paintrock Canyon Ranch in Wyoming that offers experiences for travelers of all stripes.