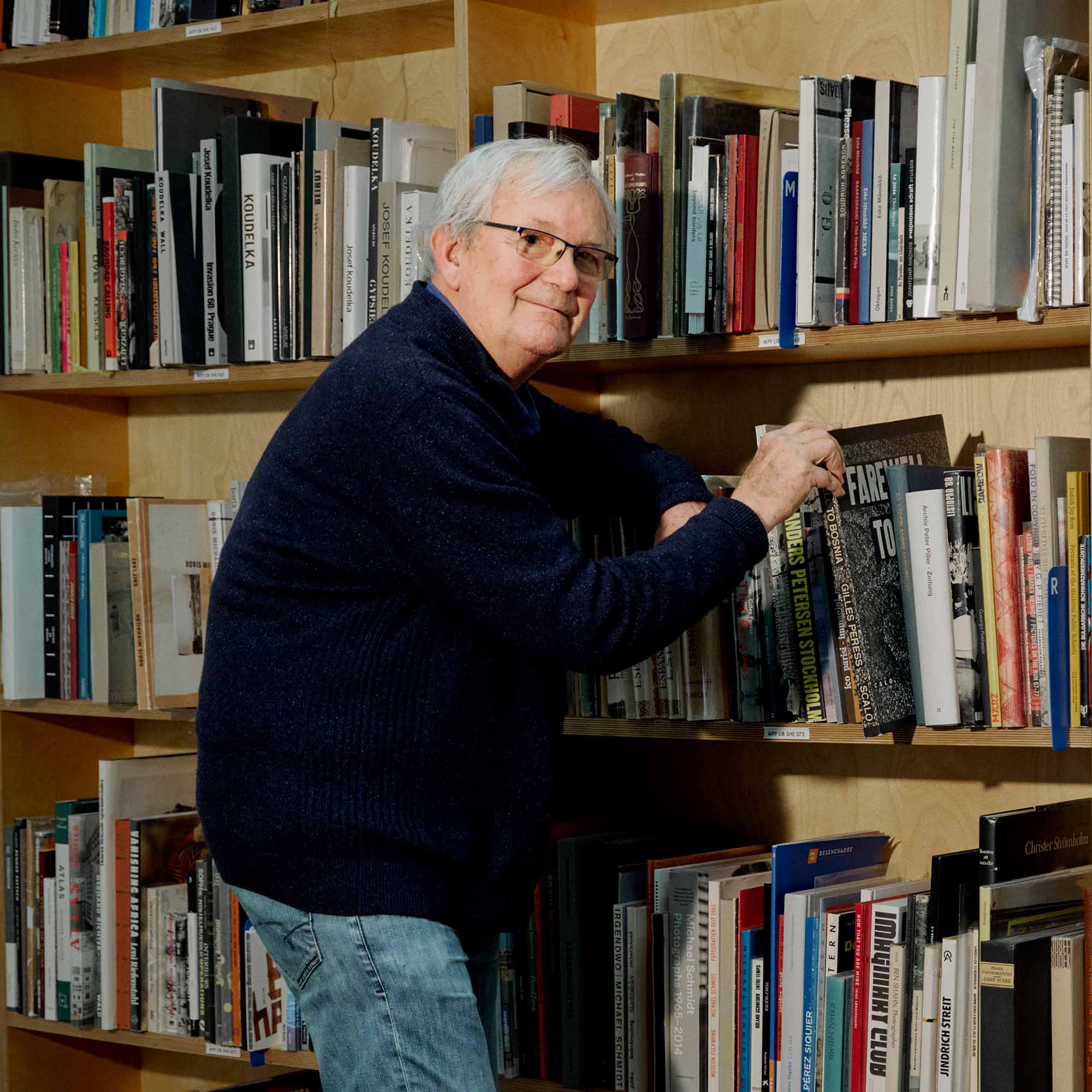

Martin Parr: A Photography Great Who Turned a Lens on Society

British photographer Martin Parr knew how to observe and highlight aspects of culture and contemporary life in both humorous and refreshingly honest ways.

Welcome to The Curator, a newsletter companion to The Grand Tourist with Dan Rubinstein podcast. Sign up to get added to the list. Have news to share? Reach us at hello@thegrandtourist.net

Earlier this year, as wildfires devastated Los Angeles, the legendary Eames House stood terrifyingly close to being lost. But when the smoke cleared, the midcentury beauty, tucked in the coastal shade of the Pacific Palisades since 1949, remained standing. Thanks to earlier landscaping efforts and luck, the house survived. Designed for themselves, the steel-and-glass house and studio, officially called Case Study House #8, was where Charles and Ray Eames lived, worked, entertained, and brainstormed. Today, the house is faithfully preserved down to its tchotchkes, remaining one of the most cohesive examples of Charles and Ray Eames’ creative ingenuity. While spared by the flames, considerable smoke damage forced the property to close for months of cleaning and restoration. This July, it’s reopening again to the public—and for the first time, so is the adjacent studio, the modest birthplace of some of the 20th Century’s most iconic furniture designs. The designer’s descendants have also recently launched the Charles & Ray Eames Foundation, a nonprofit focused on preserving not just the house, but the couple’s optimistic design ideals. That is, so future generations see design not just as mere decoration, but as a tool for living well. eamesfoundation.org

MoMA Presents A Relic of a Japanese Architectural Icon, Feminist Fiber Art Debuts at RISD, and More

New York, “The Many Lives of the Nakagin Capsule Tower” (Until July 12, 2026)

In 1972, Tokyo commuters moved into architect Kisho Kurokawa’s vision of the future: single-occupancy capsules with molded fiberglass interiors, each fitted with customizable amenities from Sony color TV to alarm clocks. The 140-module tower was one of the most emblematic examples of Kurokawa’ attempt to build urban architecture that could evolve and adapt. The capsules were originally intended to be replaced, but were instead adapted from apartments into offices, art studios, and DJ booths until the entire tower was dismantled in 2022. This exhibition presents an original salvaged capsule accompanied by photographs, drawings, archival film, and other artifacts. moma.org

Beacon, “Kishio Suga”

In a 1970 work titled Soft Concrete, Kishio Suga presented an understated but novel contradiction: a mass of oil-infused cement that wouldn’t harden. A key figure of Japan’s Mono-ha group or School of Things, Suga rejects traditional sculpture in favor of temporary “situations,” where natural and industrial materials are intentionally arranged. The works in this exhibition span the ’60s and ’90s, some coming to the States for the first time. Suga’s murder-mystery film, Being and Murder (1999), is also screening at the museum’s Chelsea location. diaart.org

London, “Emma Amos” (Until Aug. 9)

“In London, as an art student I had that wonderful feeling of release,” says artist Emma Amos. Born in segregated Atlanta, making art was always inherently political for Amos and that early stint afforded her with new artistic freedoms that helped hone her practice. After London, Amos began her career in New York where she stitched, printed, layered pigments, and painted on canvas and linen lined with fabric. This UK solo show, a first, spans five decades and features major works from her “Falling” series, where gravity is a social metaphor. alisonjacques.com

Philadelphia, “Mavis Pusey: Mobile Images” (Until Dec. 7)

In 1971, one of Mavis Pusey’s bold abstractions was shown in The Whitney’s “Contemporary Black Artists in America.” Yet, the Jamaican-born artist has slipped into obscurity today. Her long-running “Broken Construction” series, begun in New York in the 1960s, captured the demolition and construction that defined the city and American idealism. “I am inspired by the energy and the beat of the construction and demolition of these buildings,” she explained. “The tempo and movement mold into a synthesis and, and, for me, become another aesthetic of abstraction.” Before this long-overdue survey of 60 paintings, drawings, and prints, her work had yet to be fully explored. icaphila.org

Providence, “Liz Collins: Motherlode” (Until Jan. 11)

Over the last three decades, Liz Collins’ career has evolved tremendously as she challenged the limits of traditional textile art. After launching an avant-garde knitwear label in 1999, the Brooklyn-based artist pivoted from commerce to installation and performance art that often involving live knitting performances. Her abstract needleworks are joyful and unexpected. “I was and still am enthralled by how yarn carries color,” she told an interviewer, “in a way that is more dimensional than paint.” Now, RISD, where she attended and was a former professor, gives Collins her first U.S. survey. Over 80 pieces capture the experimental, refined, and monumental sides of her creativity. risdmuseum.org

British photographer Martin Parr knew how to observe and highlight aspects of culture and contemporary life in both humorous and refreshingly honest ways.

One of L.A.'s architectural treasures is taken over by an artist that uses color and design; India Mahdavi creates outerwear that makes rainy days a joy; and Jeanne Gang builds a recreational center in Brooklyn that's sorely needed.

One of the most exciting parts of traveling today? The ability to disconnect. On this episode, we explore Ranchlands, a massive land management business in the American West that includes the remote Paintrock Canyon Ranch in Wyoming that offers experiences for travelers of all stripes.