Mark Your Calendars: The Grand Tourist 2026 Guide to Art and Design Fairs

A great design or art fair sets the tone for the year, defines the conversations, and points to where taste is headed. These are the fairs defining 2026. Save the dates.

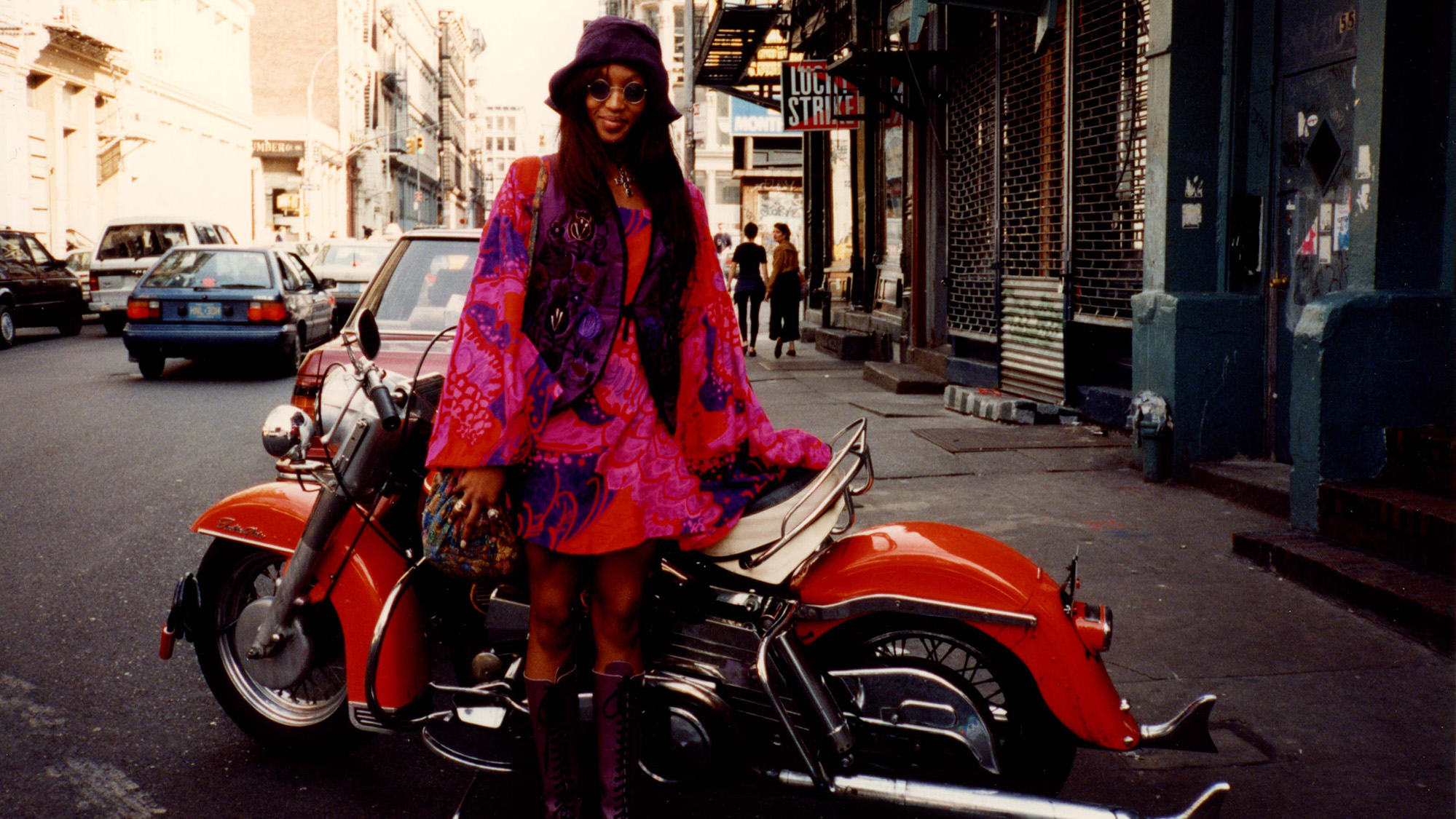

From grunge style to the preppy look, one fashion designer helped define the wildly creative 1990s, New York’s Anna Sui. In her latest book The Nineties x Anna Sui (Rizzoli), the beloved designer catalogs this momentous decade in her life and career through photographs, memories, and runway-fabulous illustrations. On this episode, she speaks to Dan about growing up as a music-obsessed teen in the Midwest, getting her start as an ambitious creative in Manhattan, meeting and working with a young Marc Jacobs, how the world of vintage shopping impacted her process, and much more.

TRANSCRIPT

Anna Sui: Let’s say you sell a million dollars of a collection. That million dollars is not yours. You have to pay all those people that made it happen. And that’s the thing that a lot of designers don’t understand, is that you need that support system and you need that team and you need that infrastructure and family to make your brand. And, you know, just because your name is on the label, it’s not just you.

Dan Rubinstein: Hi, I’m Dan Rubinstein. And this is The Grand Tourist. I’ve been a design journalist for more than 20 years, and this is my personalized guided tour through the worlds of fashion, art, architecture, food and travel. All the elements of a well-lived life. When it comes to trends, it seems like everything keeps coming back into fashion again and again. And lately, the ’90s seems to be the nostalgic golden age we keep pining for. It seems to be everywhere from baggy jeans to an obsession with pre-iPhone digital culture from CDs to flip phones. It’s all amusing to me as the ’90s were my teenage, college, and early professional years all rolled into one. Gay rights were on the rise, but still transgressive. The internet was booming in ways no one really understood. And fashion was at times ultra-expressive and understated at the same time.

My guest today is a fashion designer who was instrumental during that golden age of creativity that created numerous present-day icons, including herself, Anna Sui. As a kid growing up in the Midwest, Anna came to New York to pursue her dreams of design. And along the way, inching her way up in the industry one runway show at a time, helped create some of the signature looks that define the decade, from grunge and slipdress to all things preppy.

If you’re looking for a treasure trove of inspiration and insider gossip from that era of Sofia Coppola, nirvana, and vintage shopping, you’re in luck. Anna Sui’s latest book, The Nineties x Anna Sui, is out now from Rizzoli. I caught up with Anna from her studio right here in Manhattan to talk about growing up a child of rock and roll sounds, moving to a Big Apple that might feel unrecognizable today, how she first met Marc Jacobs and Steven Meisel, and much more.

I read that you were raised in Dearborn, and that your parents sort of met in Sorbonne, in Paris, studying there.

Yeah. Well, my mom was going to Sorbonne, and my father was going to this very famous engineering school for bridges. It’s world famous. And he already had a degree in engineering, and he studied in Paris, and then he got a scholarship to University of Michigan. So, that’s how we ended up in Michigan. So, actually, my parents met on a trip in Spain to Ávila, where there were Chinese students, and they met on the train.

Oh, wow. Fantastic. Did they ever become Francophiles?

My mom lived in Paris for almost three years. My dad lived there for two years, and then he left to go to University of Michigan and set up a house and everything. And then my mom moved to Ann Arbor, which is where University of Michigan is.

And how did they adapt to life there in the Midwest? Which to me just sounds… I mean, I went to school somewhat near the Midwest. And it’s cold.

Yeah. Yeah. I mean, keep in mind, they both lived in China. My dad was in boarding school most of his life, and it was all during the Japanese War. So, they were constantly moving, and they lived in many different climates in China. So, I think just the prospect of living in the United States was so exciting. And I think that they seemed to adapt. I’ve never heard them complain about the weather. But yeah, it was like the winters were kind of harsh, but not as hard as Chicago, let’s say, or Minneapolis.

And as a first-generation American, was it kind of a strict household?

Well, my parents were pretty international, having been educated in Europe and having lived in so many different households. And I think their life was always in flux, and when finally they settled into the Midwest, I think they just went with the flow. And this is at the height of pop culture. Everybody watched the same TV programs. It was all like a “Leave it to Beaver” world. So, they just adapted.

And we weren’t real strict on any kind of Chinese superstitions or even the holidays. We didn’t celebrate Chinese New Year or any of the interim holidays. We celebrated Christmas and Thanksgiving and Easter. So, I think they just adapted and were very modern about their whole approach.

I read that you have two brothers and as a teen, your older brother would take you to music shows in Detroit. Is that true?

Yeah. Yeah. Because in the ’60s, every band passed through Detroit. It was part of the circuit. So, first it was some local bands like Iggy and the Stooges and MC5. And then all the British Invasion was passing through. So, once I was old enough to go to the venues, I went to the venues. But those first couple of summers, I wasn’t really old enough. So, my brother would take me to the concerts in the park. And almost every weekend, we’d see different bands.

Oh, nice. What did you like personally as a young girl in terms of music?

Oh, Iggy and the Stooges, MC5. I mean, of course, as a kid, I loved The Beatles and The Monkees and a lot of that pop rock that was going on, Dino, Desi & Billy. But then as I got a little older and understood a little bit more about music and rock, I mean, Iggy and the Stooges and MC5 were just so revolutionary. And Alice Cooper. Yeah.

If you could go back in time to when you were 16 with a time machine, and you and I could visit yourself at a younger age, what would you say? How would you describe that sort of young woman?

I mean, I was always very determined to be a fashion designer. I think you probably read that when I was 5 or 6, I was a flower girl at my uncle’s wedding. And I came back to Michigan, telling everybody I was moving to New York and becoming a fashion designer. It took me all my childhood and teen years to figure out what that was and how to do it. So once I read about two young ladies going to Parsons School of Design, and reading that they were given a boutique by Elizabeth Taylor in Paris, I thought, “Okay, that’s the key, I have to go to Parsons.” And so I did everything I could in my education and took classes so that I would have the proper portfolio to register for Parsons.

So I’d say I was a very determined, focused teen. And I would sit and read Vogue magazine in school all day long, sometimes getting in trouble about it. But that was my nature. I just had to learn as much as I could about fashion and figure out, How was I going to reach this goal?

What was the biggest hurdle for you, if I were to ask a younger version of you what that was? Did you think your parents wouldn’t approve of going to New York and Parsons? Or what was the big worry in your head to figure it out after all those years?

Yeah. Because it was just, what kind of career was that? Was it a career at that point? It’s just, I want to move to New York and be a fashion designer. What does that mean? Is that a dress maker? It was just not that clear at that point.

There weren’t articles and stories about fashion designers back then. So I think once they saw how determined I was, my father even took moonlighting jobs to support my education. And I think that once I started doing fashion shows, my dad and mom were at every fashion show. My father took pictures of every show. And actually, that’s what the book is about. It’s a lot of his photos.

And we had this ritual, because it’s before digital, and he would take the pictures. And by the time we got home after the show, it was always the evening because I always had like an early evening show. Then first thing in the morning, he and I would walk to the photo shop, he would turn in the film, we’d go to the corner newsstand and see if there were any reviews in the Times or Women’s Wear.

And then we’d wait a couple of hours, and then he’d go pick up the photos. And that would be the first that I saw of the show, because you couldn’t see it. I mean, I was backstage all the time. So that would be my first clue. And I would look at the photos, not only what was on the runway, but who was in the audience. And so that would kind of tell me what press were there, what stores were there, what celebs were there. So that was our ritual all those years. So I think you’ll see that the book is kind of a very different perspective.

When your dad would help you do all of this, was he someone who would try to give advice or was just, you know, a gushing normal parent?

I mean, I think that anytime I needed advice, yes. And when I actually moved the business out of my apartment into my first workspace, he came and my younger brother Eddie came, and they helped me paint the space and he built all the cutting tables. I mean, he was just so supportive. And then at the shows, he got to know all the buyers, all the press. And actually, there’s footage of him talking with Jeanne Beker. And she’s complaining that she couldn’t get backstage and she’s asking my dad how to get backstage. It’s just, it’s just funny. Like he just knew everybody. And he was that kind of guy that could just talk to anybody. And he knew Kal Ruttenstein, he knew everybody. So, I think he started really enjoying coming to the shows.

In those early days leading up to the era that your book focuses on, when you think about your own career up to that point where the book starts to take off in the timeline, what would you say was your sort of key to fashion success? What do you think made you such a successful designer?

I think a number of things, I think the fact that I did work in the industry. For a while, I had some jobs with very big companies. And I learned the fabric resources, I think the fact that I knew resources—knew how to source not only fabric, but buttons and trims. And, you know, that was a very vital industry at that point. And all these streets were filled with stores and showrooms for fabric. So, I developed relationships with a lot of the textile companies, and found out who the owners were and started befriending the owners.

And once I started my own business, they were the ones that were really instrumental in getting me fabrics and giving me credit so that I could buy fabrics. I think working in some of these companies, I would sometimes go to the showroom to introduce the new collections. So that’s how I met Kal Ruttenstein and a lot of the fashion directors of different publications and stores.

So I mean, I understood the whole infrastructure of the business, which I think, at this point, there’s not much infrastructure. Back then it was very orderly, very scheduled. What would happen at the show is when you were greeting the guests, the first people in line were always the department stores, and they would start getting you to commit to what things they wanted for the windows, what they wanted for ads, and you had to give them exclusives. Stores would come up and say which collections they wanted or what pieces they wanted to buy. And magazines would ask you if they could be the first to photograph things. It was just very, very planned that way.

Now with it being mostly digital, it’s not quite as… you don’t have that contact. And then you also don’t have that feedback, that immediate feedback, where you’re waiting for the orders, you’re waiting for the stores. The buyers aren’t even the ones that come to the shows, you know, it’s just… and that’s so much a part of I think, New York, too. Because we’re talking about places to get trim and buttons and things like that.

That’s the Garment District, right? I mean, what we’re really talking about.

Yeah.

And then comes the 1990s, which is where the book centers on. And, you know, it was such a different place back then. Those of us, myself included, remember it.

And the book mentions a lot of things that maybe people would not have thought about when talking about fashion, but this kind of like, restaurant culture and the clubs, and Patricia Field, the famous boutique, which so many people would reference. Do you think your designs of the era were sort of like an outgrowth of that culture at the time? Or were you responding to something? Or was it a little bit of chicken and egg? Do you think that one begat the other?

Oh, definite, definite. I think that, you know, I was so obsessed and in love with fashion that I always wanted to know the latest thing. I’d always go to the latest store, I’d want to see the latest designers. And you would go to these shops to see that. I would go to the flea market every weekend researching and looking for new inspirations. And I went to every exhibition.

And, you know, I really think I got the best of all worlds in New York with not only my own obsession, but also all my friends. Like, that’s all we would talk about. We’d talk about, “Oh, there’s Claude Montana at Bloomingdale’s. You have to go see those big shoulders.” And it was just always our obsession. “Oh, the new Italian Vogue came out.” Like, “You can get it at the newsstand on like 40th and 7th Avenue.”

You know, it was just always those things that were my world and what I lived for. So, I think that, again, it’s a little different now because everything’s so immediate that I don’t know that everything’s as precious as it was back then. Because for publications, you had to wait those two or three months.

Women’s Wear Daily would have the black and white photos, but you wouldn’t see the color usually until it finally came out in editorial. And then you wouldn’t see the actual clothing until it came out six months later in the department stores. So, you would ask the salespeople, “Oh, when are you going to get that new collection?” And, you know, “When should I come to the store?” And, “Oh, we should be getting it at the end of June, beginning of July.” So, you’d go.

And then you’d also make friends with them and say, “When is it going to go on sale?” And then they say, “Oh, right after like October 15th, we start marking down.” So, it was just like all those things that kind of… I was so driven and always had to get like that piece that I saw maybe the first time in Women’s Wear Daily that I just had to have that Gaultier skirt or that Kenzo or whoever the designer that I was obsessed with. So, I think that all of that made it so much more desirable and almost like a constant quest for having to find something that you’re obsessed with and waiting for it and longing for it. And I think things felt more precious.

(SPONSOR BREAK)

I’m just curious, when you decided to sit down and do this book, why the ’90s? Why focus on this?

I wanted the newer generations to understand how genuine that period was. It wasn’t completely dominated by huge corporations that paid for front-row people and paid for celebrities to wear the clothes. Back then, it was just very organic. It was an exciting time in fashion because there was a lot going on in the arts. Not only in fashion, but in music, in film. And we were all of that generation that probably 15, 20 years before had experienced New York and the true underground New York. I met everybody at clubs, and we would all see each other night after night, check each other out, see what they were wearing.

Some people broke through all those bands from CBGBs like the Ramones and Blondie. We saw all the British bands like Sex Pistols and The Clash. They were all hanging out. You would see them play, and then you would go to the Mudd Club and they’d be hanging out at the Mudd Club. It was just much more organic. It wasn’t where you had to be paid to do something.

I think that you can really understand that when you see these pages and see what’s going on, not only on the runway, but also backstage. All those models were dating those young Hollywood stars or dating guys in the bands, and they’d be at the shows. That would be a week or two before the show. My PR would always say, “Can you stop going out? You can’t invite any more people to the show.” Whenever I met somebody, I’d say, “Oh, you have to come to my show.” And so it just was very organic. It wasn’t a paid thing. It wasn’t strategic. It was just really what was happening.

So I guess you could say, after Parsons, if you had moved to Miami or Paris or something, that your career would have turned out completely differently, and your designs might have too.

Well, you never know. I don’t know. Yeah, but I think I was very influenced by New York. Very influenced by the whole club scene that I experienced from the beginning when I moved here.

There’s also a fantastic monograph of your career and its many facets that coincided with a museum show in London in 2017. The first book is rather comprehensive and it goes through your life, but this book is also a kind of trip down memory lane with other people and other cultural phenomena. What kind of research did you need to dig up all of this?

Actually, the first book that I did was with Andrew Bolton, and it was chronological. The second one I did with Tim Blanks, and it coincided with this exhibition at the Fashion and Textile Museum. And so, we worked hand in hand with them with the archetypes of my career.

And so, we picked seven or eight categories and curated the museum show that way. But also, I spent like four days with Tim and we talked about each of those archetypes and what the influences were—what was going on in my life during the time when I was working on those. And I think that so much of what I was inspired by was nostalgia for a long time. I mean, I missed out on the ’60s. I wasn’t in London. I wasn’t on Carnaby Street. I didn’t see the Beatles, like all those things, but I was always longing for that. In the ’70s, when I finally did come to New York, it happened that I started meeting all these bands and all these artists and different people. And by the ’90s, I think that everything kind of just got on track.

Everyone was being inspired by the music. You’d go to a concert and you’d see everybody that was in town, because everybody wanted to see Nirvana or Smashing Pumpkins. And the audiences were so excited. And everyone was all dressed up and wearing the latest whatever. Or you’d go to a film premiere. And again, you’d see so many people that, again, weren’t paid to go there. They were just genuinely friends or interested. And same with the restaurants. It was always like a movable feast where you would go to a restaurant and you’d see like 10 to 20 people that you knew or wanted to know or were star struck by. But everybody would be at the same restaurant.

It’s not like today, where you go to a restaurant and it’s like, who are these people? Like, is this New York? It was a very different time. And then that restaurant would probably be it for a month or two or the summer. And then you would move on to the next place. But you were guaranteed to run into somebody and then hear about the parties or the next concerts or whatever that was going on. Because everybody depended on word of mouth then. There wasn’t everything on the internet. So, it became very exclusive for people too, because we were in the grapevine. Where now, everything is immediate and on the internet even before it happens. And then it has no underground sense about it.

So, in the ’90s, what was a typical weekend like for you?

I guess there would always be some kind of dinner or party. And then shopping because the flea market in New York was incredible. I mean, it’s probably the best flea market ever. And at one point, there were three huge parking lots that were just filled with vendors. And you would see everyone from Yves Saint Laurent to Andy Warhol to everybody shopping, depending on what time of day you went there. And then you would make friends with all of the different vendors and they would bring special stuff for you. And it would not be a matter of like—if you found something, it’d be like, “What can I afford to buy?” And like, “How much can I buy?” Because you had to choose, because there was just always so much.

I mean, I furnished all my whole stores and apartment with the amount of furniture that they had there and the great selection. You know how I have all this Rococo stuff? I had one vendor that looked out for that stuff for me. And she would send me pictures. Or she would take photographs or Polaroids and she’d say, “Okay, I can get you this. I can get you this.” And we furnished all my stores that way. Because she knew exactly the kind of Rococo Bombay shaped furniture that I liked.

That brings up such a great point about flea markets in New York and how they used to be such a big thing. And then they kind of faded away. I guess the internet must have killed it… there’s so many cities around Europe and elsewhere that have amazing flea markets to this day, even if they’re once a month or something like that.

Yeah.

When do you think that the flea market universe in New York started to fade?

Well, I think because of economics they lost those parking lot spaces. And then they moved into the garage. And so the garage was maybe 50% as good as what it was. So, there was a big decline there. And then once they lost the garage, and it’d be off and on in that parking lot where it is now, so many of the vendors were of that age. They probably retired. They couldn’t hack it anymore because it wasn’t what it had been. And I think the audience changed a lot.

People didn’t care about those antique or vintage things that my generation loved, like ’20s, ’30s, ’40s, ’50s, but mid century stuff. And they started wanting like yesterday… So, I think vintage, the resurgence of vintage has been incredible, but it started out just wanting yesterday instead of things from my mother’s era or whatever. And now it’s incredible, because you can find exactly what you didn’t get the first time around. Like, let’s say you want that Prada fairy bag. You can Google it and you can find five resources, depending on how much you want to spend for it.

But that, again, makes it that Holy Grail. And even more precious than buying a Prada bag that they have in the store right now, because that you can get, but getting that exact one that you missed out on makes it even better. So, the whole thing kind of really shifted.

To me growing up in the early ’90s as a teenager and going to school, grunge was just something that kind of happened to the world around me. So obviously, it was something that felt so normal and what being a teenager was all about. But you had a front row seat. Your ’93 collection, I believe, was pivotal in part of making this look and to what it is. And for someone listening today who might be in school, maybe a Parsons student, what is grunge, in your words?

I think it was a reaction against the big hair bands from the ’80s, which were all almost manufactured from L.A., belonging to big record companies. Very flashy and very loud. And suddenly, there were these shoegazers, these shy people that were almost more like the artists that you remember in school that probably never talked to anybody. And you didn’t realize they had this hidden talent. And they would gather at these clubs or venues and play their music, which was on a very different sound level from those metal bands. And it was much more casual. And they all had this much more casual way of dressing.

Instead of fringe leather with studs and big hair, everything was very quiet. There were flannel shirts and t-shirts and baggy jeans. And a lot of them came from the Seattle area. And there was all of a sudden new record companies, much smaller record companies and indie record companies. And even the circuit that they played was very different. It wasn’t Madison Square Garden. They were smaller venues. And so again, it felt much more intimate. And it reflected what was going on with the rest of the arts, where there was a whole new generation of filmmakers and artists. And then fashion designers followed suit. We went to see those bands. We met those bands because someone was dating somebody in the band or you’d go backstage at the show and meet them. And, you know, and it was just much more intimate. Again, it wasn’t that kind of big business that heavy metal was.

In the fashion industry, when these things went from kids finding vintage to fashion labels producing the look, were there kind of gatekeepers or buyers that were resistant to the idea? Like at the time that it was all happening? What was the meta discussion about, like, “Hey, we need to sell things people can wear to work?”

Yeah, exactly. I mean, because again, it was like power dressing from the ’80s. And suddenly, these things all look like they were from the flea market. So, the generation of buyers at that point, not all of them were wanting to make that change. They were still wanting those big shoulders and power dressing styles. It took a very savvy buyer to understand it in the beginning. And I mean, Marc is a perfect example of that, from Perry Ellis. But that was also what really brought so much attention to my clothes. And at first, people didn’t really know where to put it.

Like, they didn’t really get that it wasn’t junior fashion, and it wasn’t designer fashion. I couldn’t hang next to Calvin Klein or Donna Karan. Like, they didn’t really understand where to categorize it. And so I was really fortunate. I had a friend that worked at Calvin Klein, and he saw me on the street one day and he said, “I need to talk to you.” And, “Let’s have dinner.” And at dinner, he said, “You need to open a boutique, you have to showcase what your clothes are about.” And that’s when I opened my boutique on Greene Street. I went the very next day, found the space—it was an artist in residence building—and the rent was $5,000. And I had like a 20 year lease. So that was one of the best business deals I ever made, because it made my store really affordable.

And that was pre-Soho-boom in the ’90s. And by the end, we’d have hundreds of people coming through the store every day. I mean, at the end of the ’90s, it was just like such a boom, with all the Japanese shoppers and Chinese shoppers, and then all the tourists plus locals. It changed again, like after 2008. But at that point, it was such a boom.

Hmm. And there’s a fantastic chapter on music. Of course, we’ve been speaking about some of the big names that have come through and inspired everything. But if there was one musician that you think most impacted your work or your life, who would that be? In the ’90s, I guess we can say.

In the ’90s. Well, I would say Anita Pallenberg, because I loved her style. And I actually got to be really good friends with her in the ’90s. So, that was really fun. Going to flea markets with her, shopping with her, and just seeing how she dressed and what a distinct style she had. And how she kind of invented that look for the rock and roll woman.

But also, bands started asking me for clothes. And so I dressed a lot of the different bands during that period. And I also introduced menswear. So, my first customers for menswear were Mick Jagger and then Nick Rhodes.

But then James Iha from Smashing Pumpkins asked me to make something for him. And then I think that same summer, Anthony Kiedis bought the satin kilt skirt. And he wore it through his whole tour.

Are you someone who likes to listen to music while you work?

I do. When I’m sketching. Usually that happens on the weekends. And I usually have some rock concert going on in my head and just play the same music over and over again. During the regular week, there’s just too much else going on business-wise. It’s a little difficult and distracting because it kind of carries you away somewhere else.

And if you were sketching on a weekend, what’s a playlist or an album that has been your go-to lately?

It really depends on what the next collection is going to be about. So I think if you see my fall collection, which was about Madcap Heiress. And I was really inspired by those 1930s films about all these rich heiresses that would run off with the butler or the chauffeur.

And so I was listening to all that music and researching as much as I could and finding out, like, oh, Doris Duke’s favorite song is “I Love the Way You’re Breaking My Heart.” And so I would listen to that over and over and over again. To just kind of get the flavoring of what those women were about, what the sound was like. And imagining them dancing in El Morocco or some of the nightclubs. Or there would be other times when I was inspired by, like, maybe a different period of time. One collection that I loved, it was based on the Ballypulk.

And I worked a lot with Frédéric Sanchez on music. So, I kept calling Frédéric because he knows so much, not only about contemporary music, but historical music, opera, classic music. And I wanted to know, like, what was the music that Toulouse-Lautrec was listening to?

And that was actually at the beginning of recording. He sent me all these recordings of, like, one of those dance hall singers. And so it just helps you kind of transport and get yourself in the mood for the elements of what you’re trying to introduce into the collection. Even though it’s not like a historical recreation, you can pick up elements of that period by looking at pictures and hearing the music.

And there’s a wonderful chapter on all things preppy. Why do you think that struck a chord at the time? Because I remember preppy was—from my young point of view when I was a kid—almost transgressive slightly, I don’t know. It was radical because it felt somehow conservative. What do you credit that preppy boom in the ’90s to?

Yeah, I mean, it was kind of my way of perversing it, almost. Because it was such a classic thing and such a middle of the road thing. But how do you make it, like, more subversive? And so there’s like little jokes throughout the whole collection.

But still, it was kind of the way people were dressing with the baby tees and the little plaid skirts, and like a little cardigan. But I did them in colors that people hadn’t seen in that style before. It wasn’t like red, white, and blue. It was baby pink or baby yellow, baby blue. And Hush Puppies had just come out with their Hush Puppies again. And I got them to make special colors in all those pastels for me. Which again, was kind of like subverting it. When Hush Puppies were big, they were brown or black. Then suddenly there’s these, like, fun—like they look like candy almost. So I think that that’s something that was a lot of fun to do. And taking all those elements—I actually had a copy of the Preppy Handbook—looking at it, but subverting it.

Yeah, the Preppy Handbook. It’s one of those books, for those who might be a little bit younger, that always comes back around in the culture. People keep finding it and reprinting it.

And I have to ask about the movie Clueless, because obviously, if you’re my age, Clueless was almost like this film that is more important than almost anything in the evolution of style in the ’90s. Can you explain that connection? I believe your collection kind of inspired the costumes in the film. And it was such a big national hit.

Yeah, I think if you look at my first show, those little plaid kilts and matching jackets and the little cap, that all kind of precluded it. There’s also a bright yellow windowpane and a pink windowpane, you know, so all of that precluded that look. But I think that what happens with fashion, sometimes something sets off a look.

And it takes a while to really catch on. And so I think Clueless came out a couple years after that. Or I did that one collection that was very preppy again, and had like golf inspired clothes. And again, I subverted the golf, but it was very much like Wes Anderson’ Royal Tenenbaums, like that styling. And that became such a look. Like everybody was wearing tracksuits again. I think that it’s what fashion is about. Like you take an element that you feel is in the air and you kind of try to do your own version of it.

There’s a discussion in the book about how fashion is cyclical and the fact that the ’90s looked a little bit like the ’60s at some points. There’s a wonderful chapter about the trend of vintage clothes that we’ve spoken about. I’m wondering if, when you went shopping for vintage in New York at the time, did you have favorite spots that you would go to?

Oh yeah, definitely. But I think the flea market was the best.

Yeah.

And it was shortly after the Yves Saint Laurent Revolutionary Collection, where the women were wearing 1940s clothes. And it caused a scandal because it was so close to—I mean a lot of people still remember World War II and the occupation. I think people walked out of that show.

Top journalists like Eugenia Sheppard just were so critical about it. But again, it kind of reminded me of what happened in the ’90s with the buyers that were still left over from the ’80s and power dressing. And then suddenly when grunge started happening, they weren’t getting where it was going. But again, that’s always what fashion’s about. In the beginning when I was buying vintage, it was ’40s. There was a shop in Detroit that was on the other side of town, where if you brought in a shopping bag from the grocery store, you could fill it for $5. And they would have all these incredible ’40s jackets with shoulder pads and beading and like all the—during glam rock, all the guys were wearing those too, like wearing them with the skinny pants. And so it was such a look. And it was not that easy to find those ’40s pieces. And this shop was like chock full of that.

To the observer, there’s something about the ’90s that maybe in New York—especially coming out of the gritty ’80s—it was dangerous. And of course it was very heavy because of the AIDS crisis. And we talk a lot about that.

There’s something about the ’90s that feels fun and carefree and baby doll and clueless. There’s this emphasis on humor and youth culture. It feels pretension-less in a sense than maybe the big power suit of the ’80s. Is that fair to say? Now, with some distance looking back on that era?

Oh, definitely. And it’s pre-internet. So, I think that was the next big change that everything felt more genuine. More sincere is maybe a good word for it. I think that there were a lot of independent artists and designers, and we didn’t answer to a big corporation. I think that that made a big difference. I think that the fact that there was a whole movement of art and film and music, all kind of coming up together and it all felt so new and it was a new generation of creatives. I think that that made it different as well. I think the camaraderie of the word of mouth and having to go out to find out what else was going on that night—you went to a place for dinner, but then you would hear there was a party or a club or something else happening later in the week. You know, that was kind of great. Where now, everything is just on your phone.

Yeah, sadly.

You’ve collaborated with a lot of people over the years, and a lot of these names like Marc Jacobs and these sort of New York fixtures and musicians, it’s a lot of people focus and personality focus. But one name does come up a lot in multiple books that you’ve done, which is Stephen Meisel.

I was wondering, how did the two of you meet and why do you think you guys clicked?

We met at Parsons. I remember walking into his drawing class and dropping my art kit and thinking, “Oh my God, this is the most beautiful man I’ve ever seen.” And like, “How can I get to meet him?” It took a while because he was in illustration and I was in fashion design and we were encouraged not to mix with the other students.

Really?

Of course, what did I do? I went to the lunchroom and met the other students. And so Stephen saw me and signals me to come over and sit with him and he’s like, “Do you ever go out dancing?”

And I’m like, “No, but I’d love to.” So then we went out to clubs and like that became a regular thing because I had an apartment in midtown. So, everyone would come over to my apartment and we’d all get dressed up and we’d go out.

East Side or West Side?

East side. Yeah. So it was kind of the ritual. And even though we weren’t even really old enough to get in the clubs, we had this thing where we would get there before nine and hide in the bathroom and then wait like an hour or two. And then when people started showing up, then we would mingle.

Oh, gosh. Okay. What clubs did you go to with Stephen Meisel?

So this is like pre-Studio. So there was one club called Tamburlaine, which I remember seeing Valentino and like all the Warhol crowd, like all those people, at. And again, these weren’t huge clubs. So, it was much more intimate. Suddenly, one of Stephen’s best friends said, “Oh, I just joined a band. Do you want to come listen to me play?” And so we went, and it was the Patti Smith group. And then I remember Stephen saying, “Oh, I heard about this band, that the lead singer is really cute. Let’s go see her.” And it was Blondie. And so this is right before CBGBs happened. And then CBGB started. And there were all these bands. And then they kind of spilled over into Max’s Kansas City. So that was the ritual, going back and forth between Max’s and CBGBs every night to see the different bands. So, it was just kind of a great time for music and witnessing a whole scene happening.

If you could live the ’90s over again, what would you do differently?

Maybe try to enjoy it a little more, because I was very driven and working really hard. And I was building my own business. I had to freelance to support my business. So, I was back and forth between Italy and New York every two weeks. But there was no other way to support my business. We weren’t generating enough money. I had to get additional income. Freelancing really helped a lot. I guess that would be probably the only thing that would be different—if I could have hung out a little more. But maybe I was always the one that left early because I had to get up for work the next day or I had to get on a plane to get to Italy. And it was always that.

Is there anybody from your circle back in the ’90s that you look back on now and think, “God, I had an opportunity to hang out with that person or spend more time with them. And I just got busy and it never happened.” Is there a particular person that you can think of?

Not really, because I don’t think I really felt that deprived. I mean, if there was a concert going on in California, I would go. And if there was a band playing that night, I would go. But it was just that there was always that thing where, “I’ve got to get home because I got to get up in the morning.” It was always like I couldn’t really hang out. But then maybe there was nothing more to do that night. But I always felt like, “I’ve got to go home.”

Another name that pops up in the book is a very young Marc Jacobs. He’s always been someone who’s ahead of the curve. But I was curious, from your point of view, what was he like as a young designer way back when?

I heard about Marc through word of mouth. And also, I remember seeing a big article in Women’s Wear about his first collection, Sketchbook. And I recognized him because he worked at Charivari, which was such a great fashion store, and one of those stores that you went to to see all the latest fashion all the time. So it became kind of a Saturday ritual. So, I knew who he was. And then I started seeing him out at clubs. And we didn’t really get to be friends until the ’90s, when we found ourselves at events together all the time, and then we started going to those events together, and then we ended up doing freelance together in Italy. So that’s how we got really close.

Okay. What kind of freelance did you work on together?

Well, Franca Sozzani from Italian Vogue, she was so connected with the whole Italian fashion world. And they were always looking for designers to freelance. So, that really helped supplement the finances to pay for that fashion show, pay for the fabric.

Did you enjoy all that time in Italy?

I think it was invaluable.

Such a different place back then.

Yeah, because I mean, I never learned the language. Marc was so great. He learned Italian. But I was just, I don’t know, a dunce with that. But it was so eye-opening and working with their pattern makers, but mostly their resources, because it was so different from when I first started my collections. Everything was domestic. Everything was made in the U.S.

And this opened up a whole different world to me for resourcing. And then connections. And then I got a contract for designing shoes. So I had that license for 12 years, making handbags and shoes in Italy, which is the best place on earth for that. So it was just such a great learning experience and cultural experience.

And if you had to describe yourself in three separate words, what three separate words would you use to describe Anna Sui?

I think lucky, grateful and obsessed.

Thank you to my guest Anna Sui, as well as to everyone at Rizzoli for making this episode happen. The editor of The Grand Tourist is Stan Hall. To keep this going, don’t forget to visit our website and sign up for our newsletter, The Grand Tourist Curator at thegrandtourist.net. And follow me on Instagram @danrubinstein. Don’t forget, you can purchase the first ever print issue of The Grand Tourist online now on our website. Just a few copies left.

And follow The Grand Tourist on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you like to listen. And leave us a rating or comment. Every little bit helps. Til next time!

(END OF TRANSCRIPT)

A great design or art fair sets the tone for the year, defines the conversations, and points to where taste is headed. These are the fairs defining 2026. Save the dates.

We assembled our favorite design objects for the people on your list that have everything, including taste.

We checked in with our former podcast guests who will be inching through Miami traffic, unveiling new works, signing books and revealing new projects this year.