Martin Parr: A Photography Great Who Turned a Lens on Society

British photographer Martin Parr knew how to observe and highlight aspects of culture and contemporary life in both humorous and refreshingly honest ways.

One of the most consequential theatrical directors ever, American artist Robert Wilson has helped to revolutionize the medium. On this episode, Dan speaks with the Texas-born talent about the hyper-conservative world in which he was raised; how he studied architecture as a young man in New York; how contemporary Broadway and opera rubbed him the wrong way; one of his latest works, Mary Said What She Said, which stars French actress Isabelle Huppert; his lauded Watermill Center and what it means to him; and more.

TRANSCRIPT

Robert Wilson: I mean, people said Einstein on the Beach, the opera I made with Philip Glass was minimalist. It was Baroque. You know, 15 repeats of that, 22 repeats of this, hand gestures.

Try to do that alone and then put that with accounts that are totally different with the music. It’s not minimal. It’s very complex.

Dan Rubinstein: Hi, I’m Dan Rubinstein, and this is The Grand Tourist. I’ve been a design journalist for more than 20 years, and this is my personalized, guided tour through the worlds of fashion, art, architecture, food, and travel. All the elements of a well-lived life.

Before we get started, don’t forget that our first-ever print issue is available for order online now at thegrandtourist.net. In this 364-page hardcover volume, with three beautiful covers to choose from, you’ll find originally-commissioned photography and in-depth interviews on everything we love here at The Grand Tourist, from art and design to travel and style. Now back to the show.

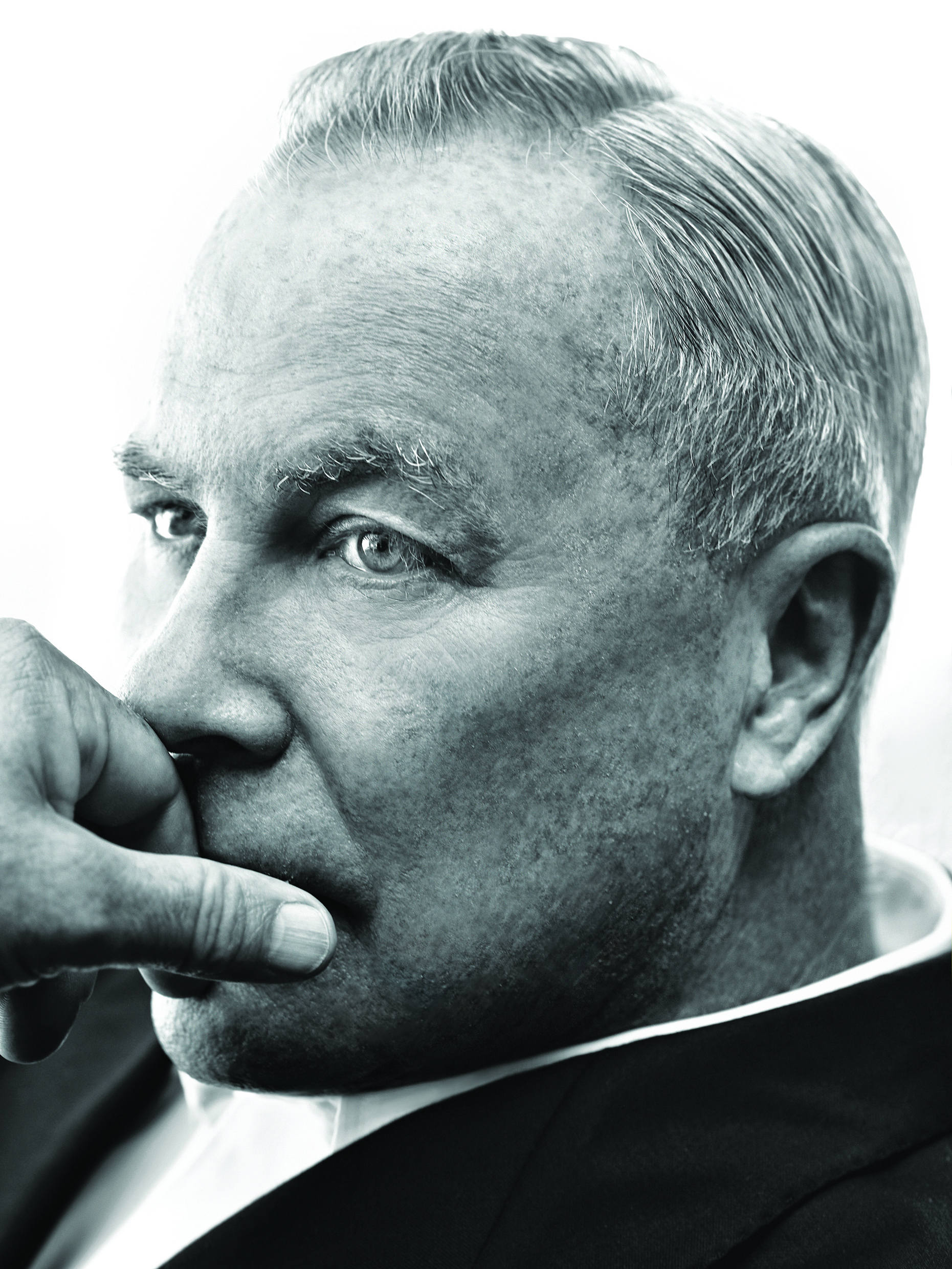

Groundbreaking, enigmatic, experimental, and with a lifelong body of work that’s simply exquisite but not always fully understood. That’s how I would describe my guest today, a true creative polymath that continues to set a standard for what’s possible in the worlds of art, theater, and performance. And he’s an American genius.

Robert Wilson. For those of you not familiar, he’s somewhat of a theatrical arts iconoclast. For decades, he’s created plays and operas that have legendarily pushed boundaries for their conceptual bents, from his best-known work 1976’s Einstein on the Beach that he created with Philip Glass and former podcast guest Lucinda Childs, to one of his more recent triumphs, Mary Said What She Said, which was staged in New York this year with the support of Dance Reflections by Van Cleef & Arpels, starring French actress Isabelle Huppert. The production, mostly Huppert on stage, decked out in a restrictive period costume for a rather intense monologue in three parts, is one of those experimental experiences that transforms a regular performance into a physical and spiritual feat of strength.

It’s classic Wilson, always challenging the viewer and always delivering something stunningly simple and also simply stunning at the same time. Robert was born and raised in Texas in the most conservative environment imaginable, and later escaped to New York in the early ’60s to dive headfirst into a creative life that would take him down a completely unique and unpredictable path. On top of his theatrical career, he’s also a painter and sculptor, famously designs chairs for his performances, and on top of it all, founded The Watermill Center, a museum of sorts in a quiet corner of the Hamptons near New York.

I caught up with Robert from The Watermill Center to discuss his upbringing in Texas, starting his creative life as an architecture student, why he dislikes Broadway so much, why the label of minimalism just really gets in his craw, and much more.

As I do with all of my guests, I’d love to start at the very beginning. I believe you grew up in Waco, Texas.

Is that true?

I grew up in Waco, Texas, and was there until the age of 17, when I went to the University of Texas.

Can you tell me your earliest memory of life in Texas?

I think the earliest memory was the backboard of a bed where I slept, and it had scratches, and I still have that image embedded in my mind. And often when I’m making drawings or staging something, that image comes to mind.

And what was your family life like? I heard that it wasn’t particularly creative.

Well, I came from a very conservative community, right-wing, religious, fanatics, racist community. You couldn’t walk down the street with a black person. In junior high school, if you’d seen someone sinning during the week, that means a woman wearing pants, someone going to a theater.

Going to the theater is like going to a whorehouse. If you’d seen someone social dancing, you could write their name on a little piece of paper on a Friday afternoon at 2:30 in the afternoon. You’d put that little piece of paper in a box, and everyone in junior high school had to pray for those names in the prayer box.

I saw you sinning, and I’m going to put your name in the prayer box, and we will pray for you.

Would you describe your upbringing as sort of middle class?

Very middle class.

And so, you know, when you’re in your late teens and you’re deciding on what to do and where to go to school, before you went to New York, you studied in Texas.

Is that right?

I went to the University of Texas, and I studied business administration, and later went into a pre-law program, and eventually then moved to New York in my early 20s to study architecture at Pratt Institute.

And when you told your parents you wanted to go forget about business or anything like that in Texas, and you want to move to New York and study architecture, what did they say?

Well, I actually wanted to study painting, and it had been in my mind for a number of years, but I knew that my father wouldn’t approve, and so I thought architecture sounded more serious. And so I told my father, and he said, “Son, to study architecture is not serious. You have to study engineering.”

But anyway, I studied architecture. I decided that I would do it on my own. I had no money, and my father gave me a little money to study in New York at Pratt, and I sent it back.

How did you support yourself?

I first worked in an Italian restaurant. I was a waiter. I was not a very good waiter, and they fired me.

And then I got another job at another Italian restaurant, and the manager says, you’re not very good at doing this, but we desperately need a dishwasher. So I was the dishwasher. And then quite early on, I worked with children with learning difficulties.

Hyperactive children considered, quote, brain damaged. I worked in and around New York. I worked at Goldwater Memorial Hospital in an island in the middle of the East River with people in iron lungs that were catatonic.

I worked as an educator and preschool programs in Harlem, Bedford-Stuyvesant, private schools in New Jersey, and that’s what I did in order to support myself.

And did any of that time with children with disabilities or anything like that, was any of that attached to your schooling?

No. It was independent. I became interested in going to museums to see works that I’d never had the advantage of seeing growing up in a small town in Texas.

I went to the theater. I disliked it strongly.

Really? Why did you dislike it? What kind of shows were you seeing back then?

I saw Broadway shows and didn’t like them so much and still don’t like them so much. And then I went to the opera, and I had a really strong dislike. It was hideous.

Acting, the scenery, the light, makeup, costumes were grotesque for me. And then I saw the work of George Balanchine in the New York City Ballet, neoclassic choreography or classical construction, and I liked that very much, and I still do. To me, he was Mozart of the 20th century.

I liked especially the abstract ballets of Balanchine, that it was a time-space construction absent of psychology.

What about it appealed to you?

I liked the way the dancers behaved on stage, how they danced with themselves first. And the audience was allowed to go to them, and they weren’t pushing too hard for the audience attention. Later, I saw the work of Merce Cunningham and John Cage, and I liked that very much as well.

And what was particularly interesting about Cage and Cunningham is that often the music of Cage was put with the dance only on the first night. So what I was seeing is what I was seeing, and what I was hearing was what I was hearing. And in this dualism, in this parallelism, it was interesting how they could reinforce one another without illustrating one another.

And I found that really interesting and fascinating. And looking back now, I think one reason I didn’t like the theater I saw in New York, that what I saw was always decoration, was always illustrating what I was hearing. Later, when I developed my own work, I was very much influenced by Cage and Cunningham and Balanchine and the formal construction, classical formula of the megastructure of the work.

My work was different than Cage and Cunningham in that although I rehearsed separately what I see and what I hear, it’s not by chance when I put them together that I make a decision. So I’m interested in what I’m seeing is one thing, but what I’m hearing can be different, but how does it consciously reinforce one another? So it’s not a collage.

It’s a constructed way of organizing time and space with something like a radio play. So if you have a radio play, you can imagine, what does Stan look like? What does Bob look like?

What does the room look like? If you turn the sound off in the TV, you begin to notice things you wouldn’t normally see, a little twitch or something, a movement of a finger. We begin to read a body language that we’re not necessarily conscious of when we are listening to the sound.

Martha Graham said, “The body doesn’t lie.” And later I adopted a deaf-mute boy, and he had never been to school. He didn’t know any words for the most part.

And he understood the world through body signs and signals, and often thought of Graham when she said, “The body doesn’t lie.”

(SPONSOR BREAK)

I wanted to go back for a second with your time at Pratt, because I read that you spent, maybe studied with, or maybe you were an intern for the architect Paolo Soleri, who did a lot of work in the American Southwest. He’s an Italian, was an Italian architect, and known for his sort of utopian structures that were quite forward-thinking. Tell me about that.

I spent a summer in Arizona working with Paolo Soleri. He was a dreamer. He was designing bridges in outer space.

He was designing cities. He would take a stick and start drawing in the desert, earth, sand, and make a shape or a form, and then we would excavate it and take that excavation and make it into mud and it became a mold for something else. But the important thing that I learned from Soleri was that he could think on an enormous scale.

Later, in my studies at Pratt, I was a student of Sibyl Moholy-Nagy. She had been married to László Moholy-Nagy, the Bauhaus architect. It was a five-year course, and the best class out of the five years, in fact, the best class I ever had in my formal education.

It was in the middle of the third year out of five. She said, “Students, you have three minutes to design a city. Ready? Go.”

Wow. You had to think big, quick.

To this day, are you someone who can think big, quick?

I try to. I directed Goethe’s Faust, part one and two, in German. I had five dramaturgs trying to talk to me about this golden cow of German literature, Faust.

It was so complicated, I couldn’t understand anything. But I had to make it very simple. Could I tell myself in one minute, what was it?

What is it? That’s the reason we work as artists, not to say what something is, but to ask what it is. We ask questions.

If we know what it is we’re doing, there’s no reason to do it. The reason to work is to say, what is it? Sybil gave a, in the five-year course of architecture, she had in back of her projections, this is early 60s, of images, a Byzantine mosaic, a Renaissance painting, a chair of Frank Lloyd Wright.

And these were changing rapidly. And she spoke, her lecture from little filing cards. And her lecture had nothing to do with the imagery in which we were seeing.

As far as I could understand, her structuring of ideas was a counterpoint. In the second year, there were three lectures in the autumn on Bauhaus architecture. First lecture was October 1st, second lecture October 20th, and the third October 27th.

And she was usually formally dressed. And she entered and stood at a podium. And she had a black leather handbag and she put it on the floor and opened it up and took out a fish.

And she put the fish on the podium and she spoke about Bauhaus architecture. I’m still thinking about that damn fish. I mean, she never explained.

And October 20th, we had Bauhaus. She puts the handbag on the floor and opens it up and takes an orange out and put it on the podium. She never said anything about the orange, but it’s still in my head.

After five years of seeing this montage of images, which she meticulously organized.

That is some real, some surreal stuff.

It seemed to me that they, first of all, were presented with theme and variation. But she never explained. But you became familiar having seen images repeating during the course of five years.

You began to know something about them. And she had a tremendous influence on all of my work and how she could think on a very large scale. Design a city in three minutes.

So you don’t think about where to put the toilets. You don’t think about the detail. What is the big idea?

So in all my work, whether it was a play that was seven hours long, a play that was 12 hours long, a play that was 24 hours long. I even made one that was seven days long. I can tell you in less than three minutes what the structure was, the big picture.

Einstein on the Beach. The first day I met Philip Glass, the opera I made with him, Einstein on the Beach. I said, “Why don’t we make an opera?”

It’s in four acts with three themes. Act one, A and B. Act two, C and A.

Act three, B and C. Act four, A, B, C together. Theme and variation.

So I can tell you in less than three minutes what was five hours long.

I’m just curious, as a young guy in New York, you’ve graduated from school. You saw theater. You didn’t like it.

What was your aspiration when you started to work in theater yourself? What was going through your head?

I didn’t know. I was very confused. I had no idea.

I didn’t do anything well. I was the worst student in school. I was always the last in my class.

I had difficulty spelling, reading difficulties. I couldn’t do well, whatever all the other kids were doing.

I also read that you had, as a child, you had a stutter. And that maybe helped you to slow down.

Yes, I stuttered until I was 17 years old. And I met a woman who taught dance in Waco, Texas. She taught ballet to young students.

She also had a very strong belief in the body healing itself. She worked with athletes with injuries or people in car accidents. And she looked at me, and I was stuttering.

My parents had taken me to St. Louis, Chicago, various places in the country to overcome the stuttering. And she said, “Bob, take more time. Slow your speech down.

Slow your speech down.” And I went home and privately did it. And within about six weeks, I had more or less overcome the stuttering.

It was as if I was speeding in place. Later, I established a foundation, and I named it after her, the Byrd Hoffman Foundation.

So, you weren’t a very good student. You had overcome a stutter. You’re in New York.

You don’t like the opera that you see, and you don’t like the Broadway shows. And so, you were confused.

I was very confused. I met Martha Graham. A friend of mine was dancing in her company, I was, I think, 21 or 22.

And she said, “And Mr. Wilson, what would you like to do in life?” And I said, “I don’t know, Ms. Graham. I have no idea.”

And she said, “Well, if you work long enough and hard enough, you’ll find something. And that very simple statement somehow stuck with me. And nine times out of ten, you know, it doesn’t work.”

And then suddenly something does work.

When did it first work for you?

I wrote a play that was seven hours long, and it was silent. And I showed it in New York. It was not very successful.

Most people left. It was not well received by critics. The New York Times said nothing happens, just some animals crawling around in a barn.

What was it called?

It was called Deafman Glance. It was based on visions, dreams of the deaf boy and ideas I had. It was performed by all the people from the various communities where I was working.

I was working in New Jersey at an arts center with housewives, and they became my actors. I included a homeless man. I included a man who lived on Park Avenue in a townhouse.

It was a mixed bag of people. Jack Lang, who at that time in the late ’60s, early ’70s, was head of the Festival de Nancy in France, and he invited me to show it two times. And I did, and much to my surprise, I had a tremendous response.

Louis Aragon wrote a letter to André Breton, his friend who had been dead for some years, and said, “Dear Andre, I’ve seen the most beautiful thing of my life.” Max Ernst said it was the most unforgettable experience. Many people from the French art community and social community, Alain Robbe-Grillet, writers, Marguerite Duras and others, were very supportive.

But having it presented at the Festival of Nancy, it was an international festival. So people from Italy, from the Far East, people from Europe had a chance to see my work. I was invited to do something at the Staatsoper in Berlin.

I was invited to do something at the Piccolo Teatro in Milano. Even La Scala offered something. But I don’t know theater, and I didn’t feel qualified.

Stephen Brecht asked me to direct the Three-Penny Opera on Broadway. I couldn’t imagine doing something on Broadway. I didn’t have the background, the skills or knowledge.

But I continued to work. The next big work I did was a man named Michel Guy. He became the Minister of Culture in France, but at that time he started the Festival of Autumn.

This was 1972, and he said, “I would like to commission you to do a work for the opening of a festival,” which is still going on, and one of the big cultural events in France each year, the Festival of Autumn. And I did the inauguration. It was a 24-hour play for one performance only at the Opéra-Comique, and it was silent.

And that was a prologue to a seven-day play that was commissioned in Persia by Farah Diba, the Shahbanu of Iran. And so I created this work on outdoors and seven foothills leading to Persepolis. We had 586 people from all over the world.

I brought housewives from New Jersey. I brought people from Latin America, North America, from Japan, from all over to participate in this international work that lasted seven days and nights, one performance only.

And when you had all this critical success in Europe, how did you think about that? Were you ever like, hey, you know what, I’m going to…

I still wanted to be a painter. But I was not a very good one. So my real ambition, I said, “Okay, I’ll just do another work in the theater to make some money until I have time to have a studio and do paintings.”

And I was about midlife going through a crisis. Really, do I want to work in theater the rest of my life? And I wasn’t sure I did.

And a man named Paul Leperk said, I was complaining that I still wanted to be a painter. And he said, “To be honest, I don’t think you’ll ever be a great painter. But you’re a great theater maker.”

And do what you do is best. And so I thought about it. And then later on, I still had reservations about continuing my work in the theater.

And I had moved to New York to go to school. And it was a great education just to be in New York and to be exposed from people all over the world, to get in an elevator with so many different people, to go to Chinatown, to go to Little Italy, or a Polish community, or whatever. So enriching.

I had recently saw Mary Said What She Said in New York, which was truly fantastic. Congratulations on that.

Well, thank you.

It’s incredibly hypnotic. And for those who haven’t seen it, it’s a mainly one-woman show with the French actress Isabelle Huppert. Tell me a little bit about this. This play is based off of sort of a short story of sorts, like a novella.

It’s based off of the life of Mary, Mary Queen of Scots. And it’s in the final moments of her life. So it’s a kind of reflection on her life and the people in her life, the dogs in her life.

It’s the amazing thing about Isabelle. I think she’s one of the most intelligent actresses we have today. She can think abstractly.

How so?

Well, most actors are trained to think psychologically or are trying to illustrate what it is that they’re saying. Most actors, they want you to identify with the situation.

Oh, you know, that’s like my Aunt Sally. So Isabelle has a way of speaking text and a kind of transparency. It’s like the weather in the room or something.

The most important thing is that it gives time to think. And I’m now absolutely sure the reason I didn’t like so much Broadway shows, I didn’t like the opera. There is no time to think.

So in my work, which is simply a time-space construction, this is quick, this is slow, this is rougher, this is smoother, this is quieter or quiet, and this is louder or whatever. What’s most important in this space-time construction, do I have time to think? Do I have time to dream?

Wow, when can we go to theater to have time for reflection? We live in cities with busy life or even here in the country where I am in Southampton. There’s so much activity.

So Isabelle, for me, is able to speak a text and the way we work with the direction is to give space. And we forget that there’s so much space in the world. A few days on an airplane, I’m going to China, working with young actors who don’t speak English.

But you look out the window of that airplane, you say, wow, there’s so much space in the world. And we forget it. So I think that’s very important, is can we have time to think?

One reason for moving from New York and to have The Watermill Center here on Long Island is to have that space, a studio of trees and skies and light, is it gives you time for reflection.

And part of Mary Said What She Said is that Isabelle is in this sort of period costume. It looks quite restrictive and with a corset and collar and the whole thing. And she’s speaking so quickly and with such precision for so long.

It’s almost like just the performance itself is this like athletic performance that’s so admirable. And it made me think of the work of Lucinda Childs who’s also had been on the podcast, who is known for this sort of athleticism in a performative way. Is that, how do you, do you create the work and then just expect the performance to kind of meet that, you know, jump through that hoop and to kind of meet that expectation?

Or is the athleticism sort of a part of the concept itself?

Well, the stage is like a battery of energies. You know, some are quicker, some are slower. Again, some are rougher, smoother.

Some need more energy. So I try again to, what is the big picture? Real quick, you know, where do you need your most energy?

I was very fortunate when I was young and had no idea I’d ever have a career in the theater. I was with Rudolf Nureyev and Margot Fonteyn after they danced Sleeping Beauty at Covent Garden. And there was a dinner afterwards and Fonteyn said to Nureyev, “If you ever partner me that way again, I won’t perform with you.”

And she says, “What do you mean?” He said, “What do you mean? We’ve had a triumph.

We had 25 minutes standing ovation.” She says, “I’m 43 and you’re 23. I can’t jump the evening the way you can.

I have to save my energy to jump here maybe for 15 seconds. I have to save my energy here to once again jump maybe for 20 seconds. And towards the end, I have to save my energy for 10 seconds.

Those are my columns and you have to help me get there.” So she was looking at Sleeping Beauty, the whole line of where she needed energy, how to conserve her energy and where to go. And Isabel said recently, someone asked her, “Oh, what is it like to work with Robert Wilson?”

And she said, “Oh, he just gives me points and then I try to find them.” So I try to make an overall structure, Mariette divided in three parts. And there are only two lines in the world, only two.

There’s a straight one and a curve, that’s all. So I said “What if Isabel, if we start with a perpendicular line to the audience, and you’re far away, let’s do it silently. Can you walk silently from the back of the stage to the audience in 30 minutes?

And can you hold my attention? No text, no music.” So my work is, again, it’s a little bit like putting a silent film together with a radio play.

And then I sometimes, with Isabel, I said, well, in all my work, but Mary, I turn all the lights out. I say, “Can you just speak the text?” So I concentrate not on what I’m seeing, but to hearing her, listening to her.

Or then I add music or sound or other things. In this dualism, how can they reinforce one another? So it’s conscious construction, time and space.

Looking at a lot of your works, sort of over time, there’s a tendency to, you have, of course, this ability to boil things down to their essential roots. And it’s something I think an architect or a designer could really identify with as a true skill. And thinking about what Mary Said What She Said, I was looking at some old photos of Madame Butterfly from, I believe it was the early 90s. Do you appreciate this concept or the word of minimalist or minimalism? And I knew you wouldn’t. No one does.

People said Einstein on the Beach, the opera I made with Philip Glass was minimalist. It was Baroque.

Teach us about the difference.

In the second scene of the first act, I mean, you have, it’s mind-boggling. I mean, do, so, do, so, do, so, fa, do, so, do, so, fa, da, la, la, la, la. You know, 15 repeats of that, 22 repeats of this.

Hand gestures, not following the music. A gesture, a pattern repeats five times, then 10 times, then five times, then 20 times, then five times, then 25. Try to do that alone, the gesture, and then put that with accounts that are totally different with the music.

It’s not minimal. It’s very complex.

Do you think it’s because people look at it and they just think of minimalism in terms of like just the scenery or like a color?

Yeah, but you know, the surface, the mystery is in the surface. What makes the surface mysterious is what is beneath the surface. So, your body, you have skin, and that’s what’s sexy and attractive.

But beneath that, you have meat, and inside the meat, you’ve got a bone. So, you have three layers of structure, skin, meat, and bones. So, on the surface, all great work, in my way of thinking, is simple.

What is King Lear, Shakespeare’s great tragedy? A man divides his kingdom. The center line of Lear, “I shall go mad,” says the king.

And then it goes into nature, the first half’s in a man-made environment. The surface, structure’s not important for me in the long run. I can’t work without structure, but it’s what you experience.

That’s what’s important. But I start with structure, and so you have a megastructure. An architect builds a building.

So, you’re in a building now in a studio, right? There are probably other rooms in the building and other functions in the building and other ways of decorating and filling in the other rooms. But the architect has made the megastructure, the building.

So, that’s what it’s like making theater. You have an overall structure, a megastructure, and then you can begin to fill it in. So, if I work with Isabel, if I work with a sound designer, if I work with a costume designer, if I work with a composer, we start with the megastructure, and then everyone can participate in filling in the megastructure to their likes and their dislike.

So, that’s what a good stage director does. That’s what a good architect does. Paris is a beautiful city because it has a beautiful plan.

And so, Frank Gehry can build a building, and it still works because there’s overall megastructure that has been thought out by an architect.

And even though you said that you were a terrible painter, and that didn’t work out for you, I’m interested in learning a little bit about your sort of video portraits.

Well, I learned to paint in other mediums. So, I learned… Actually, I, very early on, was fortunate to watch Visconti direct an opera. And he was sitting in the back of the theater.

This was in Spoleto in Italy. And he said, “Oh, put a little more yellow over there. It’s lighting.

Oh, no, no, no. It needs a little more green. No, no, it’s too much.

Put a little violet.” He was painting with light. Wow.

And he came to see one of my early works, and he said, he complimented it on my light. And I said, “Oh, Mr. Visconti. Wow.”

I cried. So, I began to do on stage what I couldn’t do or was frustrated trying to do with on a canvas. And then later, with video portraits, with light and positioning, framing of images, I was more successful than what I was trying to do with paint on the canvas.

It was painting on a different medium.

What was your first video? Do you remember the first person who sat for a video portrait?

Yeah, I do. I went in the, well, I went to ZDF, a TV channel in Germany, and asked if they would commission a series of video portraits. I had an idea of having 100 episodes. At that time, TV signed off at midnight and didn’t come on until six in the morning, and I went to play them all night. In the beginning, they said no. Eventually, they did do it. And then I had the idea of going to Sony. I went to Mr. Morita, who was head of Sony, and I had met him through a friend of mine who had the idea of Walkman and presented it to Morita. I talked to Morita. I said, “Can we change the format of the TV screen? Right now, it’s this box. It’s more horizontal than vertical.

Can we change it to a vertical format that is in proportion to the human body? Like a Chrysler painting?” He said, “Yeah, we could do it.” I had the idea of making video portraits, and I went out to the Sony plant just outside of Tokyo and met with him.

He said, “You should explain to the company your idea,” and I did. It was about nine o’clock at night, and I said, “I can’t imagine that everyone’s working here at nine o’clock at night.” He said, “Oh yeah, they are because they work for Sony.

We’re a family.” One of the guys asked me a question. I said, “Why don’t we make a video portrait right now of Mr. Morita?”

I said, “Stand on the staircase for 10 or 15 minutes. Try to think nothing.” We videotaped it, and I took the monitor and turned it on its side and put tape on the side of the monitor.

For a number of years, he had it in his office on the walls. That was the first video portrait. Later, I had the idea that I did portraits of movie stars, of people from the street.

I did animals, royalty, various portraits, but on flat screen, high definition. At that time, now they had become available. The original idea was to have the video portraits in bus stops, train stations, where people were queuing, and grocery stores, and banks.

I wanted to have them on the face of wristwatches. I went to Rolex and asked, can we have a video portrait on your wristwatch?

What did they say?

No.

I think I knew the answer to that one. Maybe now, maybe now with digital phones, you never know.

Now, it’s all happening.

I don’t know if Rolex would do it now, but I’m sure Apple would in some way.

Maybe, yeah.

You’ve done Brad Pitt, a famous one, and of course, all the ones you did with Lady Gaga. Is there a difference between doing a video portrait with someone off the street and doing one with an actor, like a film actor?

No, I don’t think so. A good actor is someone who’s comfortable with himself. All my early work, which was performed with non-professionals, if someone is comfortable with himself on stage, they can more easily relate to a public.

That’s the same with an actor. Then in my work, you saw Isabel and Mary. Actually, she’s quite awkward in the beginning.

She’s tireless and repeating. Andy Warhol said, “I want to be a machine.” Freedom is becoming a machine.

The more mechanical we become, the freer we are. Early years in watching Balanchine, there was a beautiful dancer named Allegra Kent. I used to go to see Balanchine, especially to see Allegra.

I asked her once. I saw her in her bookshop. I didn’t know her, but I went up to her and asked her about a certain movement she did in one of Balanchine’s ballets.

She said, “Oh, I have no idea, but when I’m doing it, I know.” It was in the muscle. The mind is a muscle.

Becoming mechanical, you become freer. Charlie Chaplin was sometimes 350 takes of a scene. So the first time you do something can be spontaneous.

But to learn that, again, to go back through the painful time it takes. I was here, I went there, I did that, and then I went here, and then I did that. To learn that again, to put it together, takes a long time until it becomes free again.

So contrary to what most people think, the more mechanical one becomes, the freer you are.

Not really related to that, but I guess you could probably say that it is. You’ve done a lot of work over time designing chairs, and you collect chairs. There’s also a show at, I believe it’s closed now, but there was a recent show at Raisonné Gallery in New York of your chairs.

There’s also a new book from August Editions by our friend of the show, Dung Ngo. Why chairs? How did that sort of love affair begin?

Was it literally just creating a chair for a work?

I had an uncle who lived in Alamogordo, New Mexico, and I went at Thanksgiving when I was about, maybe 11 or 12 years old. He was a recluse. He lived in the white sand desert in Alamogordo, New Mexico in an adobe house that he had painted white.

It was this white building in a white desert. He had in one room a mattress on the floor with a cover of a Navajo chieftain blanket. The next room was a series of pots, Native American pots on the floor.

But in another room there was a chair, only one chair, a rather thin, narrow chair. I said to my Uncle Sherrod, I said, “That’s a very beautiful chair.” The following Christmas, he sent it to me as a present.

I wanted to live like my Uncle Sherrod. I wanted to move everything out of my bedroom and the family home in Waco and have only this chair. I somewhat was successful.

Then I was leaving to go to the University of Texas. My freshman year, I was 17. My cousin, my Uncle’s son, wrote me a letter and said, “My Dad gave you this chair.

It’s mine and I want it back.” So I sent it to him. He lived in California.

That was the beginning of my interest in chairs. I think of what Gertrude Stein said. They said, “Oh, Miss Stein, what do you think of modern art?”

She said, “I’d like to look at it.” So that’s what I think about chairs. I like to look at them.

And as a child at my family home, I used to take the chairs away from the wall. They were all shoved against the wall and put them out in space. They were like sculpture.

I could walk around them.

What’s next for you? What does Robert Wilson do for summer?

I’m funding a program with children’s art. And we have, we’re going to show hundreds of works of children’s drawings. And it goes back to my deep interest and commitment to education.

And a group of very interesting artists are giving us works or donating works to support this exhibition of children’s art.

Thank you to my guest Robert Wilson and to everyone at The Watermill Center and Van Cleef & Arpels for making this episode happen. The editor of The Grand Tourist is Stan Hall. To keep this going, don’t forget to visit our website and sign up for our newsletter The Grand Tourist Curator at thegrandtourist.net. And follow me on Instagram @danrubinstein. And you can purchase the first ever print issue of The Grand Tourist online now on our website thegrandtourist.net. And don’t forget to follow The Grand Tourist on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you like to listen. And leave us a rating or comment. Every little bit helps. Till next time!

(END OF TRANSCRIPT)

British photographer Martin Parr knew how to observe and highlight aspects of culture and contemporary life in both humorous and refreshingly honest ways.

One of L.A.'s architectural treasures is taken over by an artist that uses color and design; India Mahdavi creates outerwear that makes rainy days a joy; and Jeanne Gang builds a recreational center in Brooklyn that's sorely needed.

One of the most exciting parts of traveling today? The ability to disconnect. On this episode, we explore Ranchlands, a massive land management business in the American West that includes the remote Paintrock Canyon Ranch in Wyoming that offers experiences for travelers of all stripes.